Thoughts on the education of daughters: with reflections on female conduct, in the more important duties of life is the first published work of the British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. Published in 1787 by her friend Joseph Johnson, Thoughts is a conduct book that offers advice on female education to the emerging British middle class. Although dominated by considerations of morality and etiquette, the text also contains basic child-rearing instructions, such as how to care for an infant.

An early version of the modern self-help book, the 18th-century British conduct book drew on many literary traditions, such as advice manuals and religious narratives. There was an explosion in the number of conduct books published during the second half of the 18th century, and Wollstonecraft took advantage of this burgeoning market when she published Thoughts. However, the book was only moderately successful: it was favourably reviewed, but only by one journal and it was reprinted only once. Although it was excerpted in popular contemporary magazines, it was not republished until the rise of feminist literary criticism in the 1970s.

Like other conduct books of the time, Thoughts adapts older genres to the new middle-class ethos. The book encourages mothers to teach their daughters analytical thinking, self-discipline, honesty, contentment in their social position, and marketable skills (in case they should ever need to support themselves). These goals reveal Wollstonecraft's intellectual debt to John Locke; however, the prominence she affords religious faith and innate feeling distinguishes her work from his. Her aim is to educate women to be useful wives and mothers, because, she argues, it is through these roles that they can most effectively contribute to society. The predominantly domestic role Wollstonecraft outlines for women—a role that she viewed as meaningful—was interpreted by 20th-century feminist literary critics as paradoxically confining them to the private sphere.

Although much of Thoughts is devoted to platitudes and advice common to all conduct books for women, a few passages anticipate Wollstonecraft's feminist arguments in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), such as her poignant description of the suffering single woman. However, several critics suggested that such passages only seem to have radical undertones in light of Wollstonecraft's later works.

Biographical background

Like many impoverished women during the last quarter of the eighteenth century in Britain, Wollstonecraft attempted to support herself by establishing a school; she, her sister, and a close friend founded a school in the Dissenting community of Newington Green. However, in the late 1780s she was forced to close it because of financial difficulties. Desperate to escape from debt, Wollstonecraft wrote her first book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, and sold the copyright for only ten guineas to Joseph Johnson, a publisher recommended to her by a friend. Wollstonecraft and Johnson became friends and he encouraged her writing throughout her life.[1]

Wollstonecraft next tried her hand at being a governess, but she chafed at her lowly position and refused to accommodate herself to her employers. The modest success of Thoughts and Johnson's encouragement emboldened Wollstonecraft to embark on a career as a professional writer, a precarious and somewhat disreputable profession for women during the 18th century. She wrote to her sister that she was going to become the "first of a new genus" and published Mary: A Fiction, an autobiographical novel, in 1788.[2]

Overview

Addressed to mothers, young women, and teachers, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters explains how to educate a woman from infancy through marriage. Its twenty-one chapters are not arranged in any particular order and cover a wide variety of topics. The first two chapters, "The Nursery" and "Moral Discipline", offer advice on shaping the child's "constitution" and "temperament", arguing that the formation of the rational mind must begin early. These chapters also offer specific recommendations regarding the care of infants and endorse breastfeeding (a hotly debated topic in the 18th century).[3] Much of the book criticizes what Wollstonecraft considers the damaging education usually offered to women: "artificial manners", card-playing, theatre-going, and an emphasis on fashion. She complains, for example, that women "squander" their money on clothing, "which if saved for charitable purposes, might alleviate the distress of many poor families, and soften the heart of the girl who entered into such scenes of woe".[4]

In her later works, such as A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), Wollstonecraft repeatedly returns to the topics addressed in Thoughts, particularly the virtue of hard work and the imperative for women to learn useful skills. Wollstonecraft suggests that the social and political life of the nation would greatly improve if women were to acquire valuable skills instead of being mere social ornaments.[5]

Genre: the conduct book

Between 1760 and 1820, conduct books reached the height of their popularity in Britain; one scholar refers to the period as "the age of courtesy books for women".[6] As Nancy Armstrong writes in her seminal work on this genre, Desire and Domestic Fiction (1987): "so popular did these books become that by the second half of the eighteenth century virtually everyone knew the ideal of womanhood they proposed".[7]

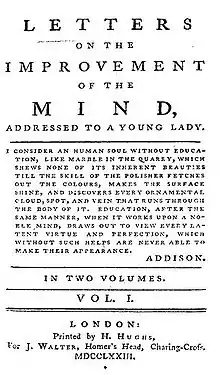

Conduct books integrated the styles and rhetorics of earlier genres, such as devotional writings, marriage manuals, recipe books, and works on household economy. They offered their readers a description of (most often) the ideal woman while at the same time handing out practical advice. Thus, not only did they dictate morality, but they also guided readers' choice of dress and outlined "proper" etiquette.[8] Typical examples include Bluestocking Hester Chapone's Letters on the Improvement of the Mind (1773), which went through at least sixteen editions in the last quarter of the 18th century, and the classically educated historian Catharine Macaulay's Letters on Education (1790).[9] Chapone's work, in particular, appealed to Wollstonecraft at this time and influenced her composition of Thoughts because it argued "for a sustained programme of study for women" and was based on the idea that Christianity should be "the chief instructor of our rational faculties".[10] Moreover, it emphasized that women should be considered rational beings and not left to wallow in sensualism.[11] When Wollstonecraft wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, she drew on both Chapone and Macaulay's works.[12]

Conduct books have traditionally been viewed by scholars as an integral factor in the creation of a bourgeois sense of self.[13] The conduct book "helped to generate the belief that there was such a thing as a 'middle class' and that the modest, submissive but morally and domestically competent woman it described was the first 'modern individual'".[14] By developing a specifically bourgeois ethos through genres such as the conduct book, the emerging middle class challenged the primacy of the aristocratic code of manners.[15] However, conduct books simultaneously constricted women's roles, propagating what has been called "the angel in the house" image (alluding to Coventry Patmore's poem of that name). Women were encouraged to be chaste, pious, submissive, modest, selfless, graceful, pure, delicate, compliant, reticent, and polite.[16]

More recently, a few scholars have argued that conduct books should be differentiated more carefully and that some of them—such as Wollstonecraft's Thoughts—transformed traditional female advice manuals into "proto-feminist tracts".[17] These scholars view Thoughts as part of a tradition that adapted older genres to a new message of female empowerment, genres such as advice manuals for women's education, moral satires, and moral and spiritual works by religious Dissenters (those not associated with the Church of England).[18] Wollstonecraft's text resembles conventional conduct books in promoting self-control and submission, traits that were supposed to attract a husband. Yet at the same time, the text challenges this portrait of the "proper lady" by introducing strains of religious Dissent that promote equality of the soul. Thus, Thoughts appears to be torn between several sets of binaries, such as compliance and rebellion; spiritual meekness and rational independence; and domestic duty and political participation. This view of the conduct book, and of Thoughts in particular, questions the earlier interpretation of the genre as a mere tool of ideological indoctrination, an interpretation that grew out of criticism influenced by theorists such as Michel Foucault.[19]

Pedagogical theory

By the end of her life, Wollstonecraft had been involved in almost every arena of education: she had been a governess, a teacher, a children's writer, and a pedagogical theorist. Most of her works deal with education in some way. For example, her two novels are bildungsromane (novels of education); she translated educational works such as Christian Gotthilf Salzmann's Elements of Morality; she wrote a children's book, Original Stories from Real Life (1788); and her Vindication of the Rights of Woman is largely an argument for the value of female education. As is evidenced by this broad range of genres, "education" for Wollstonecraft and her contemporaries included much more than scholastic training; it encompassed everything that went into forming a person's character, from infant swaddling to childhood curricular choices to adolescent leisure activities.[20]

Wollstonecraft and other political radicals during the last quarter of the 18th century focused their reform efforts on education because they believed that if people were educated correctly, Britain would experience a moral and political revolution. Religious Dissenters, especially, embraced this view; Wollstonecraft's philosophy in Thoughts and elsewhere closely resembles that of the Dissenters she met while teaching in Newington Green, such as the theologian, educator, and scientist Joseph Priestley and the minister Richard Price. Dissenters "were most concerned with molding children into people of good moral character and habits".[21] However, political conservatives, who also believed that childhood was the crucial time for the formation of a person's character, used their own educational works to deflect rebellion by promoting theories of compliance. Liberals and conservatives alike subscribed to Lockean and Hartleian associationist psychology: that is, they believed that a person's sense of self was built up through a set of associations made between things in the external world and ideas in the mind. Both Locke and Hartley had argued that the associations formed in childhood were nearly irreversible and must thus be formed with care.[22] Locke famously advised parents to keep their children away from servants, as they would only tell children frightening stories that would foster a fear of the dark.[23]

Wollstonecraft was significantly influenced by Locke's Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693) (her title alludes to it) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Emile (1762), the two most important pedagogical treatises of the 18th century. Thoughts follows in the Lockean tradition with its emphasis on a parent-directed domestic education, a distrust of servants, a banning of superstitious and irrational stories (e.g. fairy tales), and an advocacy of clear rules. Wollstonecraft breaks from Locke, however, in her emphasis on piety and her insistence that the child has "innate" feelings that guide her towards virtue, ideas likely drawn from Rousseau.[24]

Themes

Thoughts advocates several educational goals for women: independent thought, rationality, self-discipline, truthfulness, acceptance of one's social position, marketable skills, and faith in God.[25]

Education of women

Wollstonecraft assumes that the "daughters" in her book will one day become mothers and teachers. She does not propose that women abandon these traditional roles, because she believes that women can most effectively improve society as pedagogues.[26] Wollstonecraft and other writers as diverse as the evangelical moralist Hannah More, the historian Catharine Macaulay, and the feminist novelist Mary Hays, argue that since women are the primary caregivers of the family and educators of children, they should be given a sound education.[26] Thoughts is insistent, following Locke and associationist psychology, that a poor education and an early marriage will ruin a woman.[26] Wollstonecraft argues that if no attention is paid to girls as they are growing, they will turn out poorly and marry while still intellectual and emotional children. Such wives, she contends, perform no useful role in society and, indeed, contribute to its immorality.[26] She expanded upon this argument five years later in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.[26]

Wollstonecraft and others criticized the traditional "accomplishment"-based education traditionally offered women; they argued that this kind of education, which emphasized the acquisition of skills such as drawing and dancing, was useless and decadent.[27] The ideal woman in Thoughts is, as Wollstonecraft scholar Gary Kelly writes, "rational, provident, realistic, self-disciplined, self-conscious and critical", an image that resembles that of the professional man. Wollstonecraft argues that women should have all of the intellectual and moral training given to men, though she does not provide women with a place to use these new skills beyond the home.[28]

Wollstonecraft's feminist critics charged that the masculine role for women that she envisioned—one designed for the public sphere but which women could not perform in the public sphere—left women without a specific social position. They saw it as ultimately confining and limiting—as offering women more in the way of education without a real way to use it.[15]

Wollstonecraft's acerbic contempt for the low quality of women's career opportunities is without precedent for the period.[29] In the chapter entitled "Unfortunate Situation of Females, Fashionably Educated, and Left without a Fortune" she writes, perhaps describing her own experiences:

[T]o be an humble companion to some rich old cousin... It is impossible to enumerate the many hours of anguish such a person must spend. Above the servants, yet considered by them as a spy, and ever reminded of her inferiority when in conversation with the superiors. … A teacher at a school is only a kind of upper servant, who has more work than the menial ones. A governess to young ladies is equally disagreeable. … life glides away, and the spirits with it; 'and when youth and genial years are flown,' they have nothing to subsist on; or, perhaps, on some extraordinary occasion, some small allowance may be made for them, which is thought a great charity. … It is hard for a person who has a relish for polished society, to herd with the vulgar, or to condescend to mix with her formal equals when she is considered in a different light... How cutting is the contempt she meets with!—A young mind looks round for love and friendship; but love and friendship fly from poverty: expect them not if you are poor![30]

Religion

Although Wollstonecraft's comments on female education hint at some of her more radical arguments in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, she largely upholds the conventions of female conduct manuals.[31] While she does not break with the tradition of encouraging resignation in response to unideal circumstances, Wollstonecraft draws on religious tones in the Dissent tradition, that resignation can be pleasureful or sublime. These overtones are echoed in her first novel, Mary: A Fiction. Inchoate dissatisfaction with one's circumstances is expressed as yearning for the possibility of alternatives.[32] Wollstonecraft writes:

He who is training us up for immortal bliss, knows best what trials will contribute to make us [virtuous]; and our resignation and improvement will render us respectable to ourselves, and to that Being, whose approbation is of more value than life itself.[33]

Although she drifted away from these beliefs and later adopted a more permissive theology, Thoughts is "steeped in orthodox attitudes, advocating 'fixed principles of religion' and warning of the dangers of rationalist speculation and deism".[34] Wollstonecraft even agrees with Rousseau that women should be taught religious dogma rather than theology; clear rules, she maintains, will restrain their passions.[34]

Reception

Thoughts was only moderately successful: it was reprinted in Dublin a year after its initial publication in London, extracts were published in The Lady's Magazine, and Wollstonecraft included excerpts from it in her own Female Reader (1789), an anthology of writings designed "for the Improvement of Young Women". The English Review noticed Thoughts favourably:

These thoughts are employed on various important situations and incidents in the ordinary life of females, and are, in general, dictated with great judgment. Mrs. Wollstonecraft appears to have reflected maturely on her subject; … while her manner gives authority, her good sense adds irresistible weight to almost all her precepts and remarks. We should therefore recommend these Thoughts as worthy the attention of those who are more immediately concerned in the education of young ladies.[35]

No other journal reviewed the book and Thoughts was not reprinted until the late 20th century, when there was a resurgence of interest in Wollstonecraft among feminist literary critics.[36]

Alan Richardson, a scholar of 18th-century education, points out that if Wollstonecraft had not written A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, it is unlikely that Thoughts would have been considered progressive or even worthy of notice.[37] One critic said that the text reads as if it were simply trying to please the public.[38] Although some scholars have argued that there are glimmers of Wollstonecraft's radicalism in this text, they admit that the "potential for critique remains largely latent".[39] Thoughts is therefore usually interpreted either teleologically, as a first step towards the more radical Rights of Woman, or dismissed as a "politically naïve potboiler" written prior to Wollstonecraft's conversion to radicalism while she was writing the Rights of Men.[17]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Sapiro, 13; 239; Taylor, 6–7; Jones, "Literature of advice", 120; Richardson, 24–25; Todd, 75–77.

- ↑ Sapiro, 13; 239; Taylor, 6–7; Jones, "Literature of advice", 120; Richardson, 24–25; Todd, 75–77.

- ↑ Todd, 257–58.

- ↑ Wollstonecraft, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787), 37.

- ↑ Taylor, 32; Kelly, 29–30; Sapiro, 13; Richardson, 26; Jones, "Literature of advice", 127.

- ↑ Qtd. in Armstrong, 61.

- ↑ Armstrong, 61.

- ↑ Sutherland, 26.

- ↑ Sutherland, 28; 35.

- ↑ Sutherland, 29.

- ↑ Sutherland, 41.

- ↑ Sutherland, 42–43.

- ↑ Jones, "Literature of advice", 121; see Mary Poovey's The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer and Nancy Armstrong's Desire and Domestic Fiction for discussions of the conduct book.

- ↑ Jones, "Literature of advice", 121.

- 1 2 Kelly, 31.

- ↑ Gubar, Susan and Sandra Gilbert. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press (1984), 23.

- 1 2 Jones, "Literature of advice", 122.

- ↑ Jones, "Literature of advice", 122–23.

- ↑ Jones, "Literature of advice", 128–29; see also Poovey, 55 and Jones, "Literature of advice", 126.

- ↑ Sapiro, 13; 239; Richardson, 24.

- ↑ Sapiro, 239.

- ↑ Richardson, 24–25; Sapiro, 239.

- ↑ Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Ed. Roger Woolhouse. New York: Penguin Books (1997), 357.

- ↑ Sapiro, 13; 239–40; Richardson 24–27; Jones, "Literature of advice", 125.

- ↑ Sapiro, 104; 240; Taylor, 32; Richardson, 26; Kelly, 29–31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richardson, 25–27; Jones, "Literature of advice", 124.

- ↑ Taylor, 34; Richardson, 25.

- ↑ Kelly, 30.

- ↑ Richardson, 27.

- ↑ Wollstonecraft, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787), 69–74.

- ↑ Jones, "Literature of advice", 123–24.

- ↑ Jones, "Literature of advice", 124–25.

- ↑ Wollstonecraft, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787), 78.

- 1 2 Taylor, 95.

- ↑ Qtd. in Jones, "Literature of advice", 129.

- ↑ Sapiro, 13; 20; Jones, "Literature of advice", 129; Wardle, 52–53.

- ↑ Richardson, 26.

- ↑ Kelly, 34; Richardson, 26.

- ↑ Jones, "Literature of advice", 124.

Modern reprints

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. Thoughts on the Education of Daughters. Clifton, NJ: A. M. Kelley, 1972. ISBN 0-678-00901-5.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. Thoughts on the Education of Daughters. Oxford: Woodstock Books, 1994. ISBN 1-85477-195-7.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. Thoughts on the Education of Daughters. London: Printed by J. Johnson, 1787. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (by subscription only). Retrieved on 18 July 2007.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. The Complete Works of Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Janet Todd and Marilyn Butler. 7 vols. London: William Pickering, 1989. ISBN 0-8147-9225-1.

Bibliography

- Armstrong, Nancy. Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-19-506160-8.

- Jones, Vivien. "Mary Wollstonecraft and the literature of advice and instruction". The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Claudia Johnson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-78952-4.

- Kelly, Gary. Revolutionary Feminism: The Mind and Career of Mary Wollstonecraft. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992. ISBN 0-312-12904-1.

- Poovey, Mary. The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984. ISBN 0-226-67528-9.

- Richardson, Alan. "Mary Wollstonecraft on education". The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Claudia Johnson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-78952-4.

- Sapiro, Virginia. A Vindication of Political Virtue: The Political Theory of Mary Wollstonecraft. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992. ISBN 0-226-73491-9.

- Sutherland, Kathryn. "Writings on Education and Conduct: Arguments for Female Improvement". Women and Literature in Britain 1700–1800. Ed. Vivien Jones. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-521-58680-1.

- Taylor, Barbara. Mary Wollstonecraft and the Feminist Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-66144-7.

- Todd, Janet. Mary Wollstonecraft: A Revolutionary Life. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000. ISBN 0-231-12184-9.

- Wardle, Ralph M. Mary Wollstonecraft: A Critical Biography. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1951. OCLC 361220

Further reading

- Moran, Michael G., ed. (1994). "Mary Wollstonecraft". Eighteenth-century British and American Rhetorics and Rhetoricians: Critical Studies and Sources. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-27909-6.

- Palmer Cooper, Joy A., ed. (2016). "Mary Wollstonecraft". Routledge Encyclopaedia of Educational Thinkers. New York: Routledge. pp. 77–80. ISBN 978-1-317-57698-3.

External links

.jpg.webp)