J. R. R. Tolkien derived the characters, stories, places, and languages of Middle-earth from many sources. Among these are several modern works of fiction. These include adventure stories from Tolkien's childhood, such as books by John Buchan and H. Rider Haggard, especially the 1887 She: A History of Adventure. Tolkien stated that he used the fight with werewolves in Samuel Rutherford Crockett's 1899 historical fantasy The Black Douglas for his battle with wargs.

Tolkien appears to have made use, too, of early science fiction, such as H. G. Wells's subterranean Morlocks from the 1895 The Time Machine and Jules Verne's hidden runic message in his 1864 Journey to the Center of the Earth.

A major influence was the Arts and Crafts polymath William Morris. Tolkien wanted to imitate his prose and poetry romances such as the 1889 The House of the Wolfings, and read his 1870 translation of the Völsunga saga when he was a student. Further, as Marjorie Burns states, Tolkien's account of Bilbo Baggins and his party setting off into the wild on ponies resembles Morris's account of his travels in Iceland in several details.

Tolkien's other writings have been described by Anna Vaninskaya as fitting into the romantic Little Englandism and anti-statism of 20th century writers like George Orwell and G. K. Chesterton. His The Lord of the Rings was criticized by postwar literary figures like Edwin Muir and dismissed as non-modernist, but accepted by others such as Iris Murdoch.

Context

J. R. R. Tolkien was a scholar of English literature, a philologist and medievalist interested in language and poetry from the Middle Ages, especially that of Anglo-Saxon England and Northern Europe. His professional knowledge of works such as Beowulf shaped his fictional world of Middle-earth, including his fantasy novel The Lord of the Rings.[T 1][1] This did not prevent him from making use of modern sources as well;[2] in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, Dale Nelson discusses 25 authors whose works are paralleled by elements in Tolkien's writings.[3]

Adventure stories from Tolkien's childhood

In the case of a few authors, such as John Buchan and H. Rider Haggard, it is known that Tolkien enjoyed their adventure stories.[3][4] Tolkien stated that he "preferred the lighter contemporary novels", such as Buchan's.[4] Critics have detailed resonances between the two authors.[3][5] The poet W. H. Auden compared The Fellowship of the Ring to Buchan's thriller The Thirty-Nine Steps.[6] Nelson states that Tolkien responded rather directly to the "mythopoeic and straightforward adventure romance" in Haggard.[3] Tolkien wrote that stories about "Red Indians" were his favourites as a boy; Shippey likens the Fellowship's trip downriver, from Lothlórien to Tol Brandir "with its canoes and portages", to James Fenimore Cooper's 1826 historical romance The Last of the Mohicans.[7] Shippey writes that in the scene in the Eastemnet, Éomer's riders of Rohan circle "round the strangers, weapons poised" in a way "more like the old movies' image of the Comanche or the Cheyenne than anything from English history".[8]

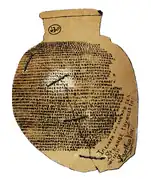

When interviewed in 1966, the only book Tolkien named as a favourite was Rider Haggard's 1887 adventure novel She: "I suppose as a boy She interested me as much as anything—like the Greek shard of Amyntas [Amenartas], which was the kind of machine by which everything got moving."[9] A facsimile of this potsherd appeared in Haggard's first edition, and the ancient inscription it bore, once translated, led the English characters to She's ancient kingdom, perhaps influencing the "Testament of Isildur" in The Lord of the Rings[10] and Tolkien's efforts to produce a realistic-looking page from the Book of Mazarbul, a record of the fate of the Dwarf colony in Moria.[11] Critics starting with Edwin Muir[12] have found resemblances between Haggard's romances and Tolkien's.[13][14][15] Jared Lobdell has compared Saruman's death to the sudden shrivelling of Ayesha when she steps into the flame of immortality.[3]

Scholars have commented, too, on the similarities between Tolkien's monstrous Gollum and the evil and ancient hag Gagool in Haggard's 1885 novel King Solomon's Mines.[14] Gagool appeared as

a withered-up monkey [that] crept on all fours ... a most extraordinary and weird countenance. It was (apparently) that of a woman of great age, so shrunken that in size it was no larger than that of a year-old child, and was made up of a collection of deep yellow wrinkles ... a pair of large black eyes, still full of fire and intelligence, which gleamed and played under the snow-white eyebrows, and the projecting parchment-coloured skull, like jewels in a charnel-house. As for the skull itself, it was perfectly bare, and yellow in hue, while its wrinkled scalp moved and contracted like the hood of a cobra."[14]

Tolkien wrote of being impressed as a boy by Samuel Rutherford Crockett's 1899 historical fantasy novel The Black Douglas and of using its fight with werewolves for the battle with the wargs in The Fellowship of the Ring.[T 2] Critics have suggested other incidents and characters that it could possibly have inspired.[T 3][16][3] Tolkien stated that he had read many of Edgar Rice Burroughs' books, but denied that the Barsoom novels influenced his giant spiders such as Shelob and Ungoliant: "Spiders I had met long before Burroughs began to write, and I do not think he is in any way responsible for Shelob. At any rate I retain no memory of the Siths or the Apts."[17]

The Fellowship of the Ring's trip downriver has been likened to events in the 1826 The Last of the Mohicans.[7]

The Fellowship of the Ring's trip downriver has been likened to events in the 1826 The Last of the Mohicans.[7] Rider Haggard's "sherd of Amenartas" for his 1887 She may have inspired Tolkien's facsimile Book of Mazarbul.[11]

Rider Haggard's "sherd of Amenartas" for his 1887 She may have inspired Tolkien's facsimile Book of Mazarbul.[11].jpg.webp)

_-_battle_with_the_werewolves.jpg.webp) Tolkien based his battle with the wargs on the werewolf fight in Samuel Rutherford Crockett's 1899 The Black Douglas.[16]

Tolkien based his battle with the wargs on the werewolf fight in Samuel Rutherford Crockett's 1899 The Black Douglas.[16]

Fantasy and science fiction

Tolkien read and made some use of modern fantasy, such as George MacDonald's The Princess and the Goblin. Edward Wyke-Smith's Marvellous Land of Snergs, with its "table-high" title characters, influenced the incidents, themes, and depiction of Hobbits.[T 4][19] Books by Tolkien's fellow-Inkling Owen Barfield contributed to his world-view of decline and fall, particularly the 1928 Poetic Diction.[20]

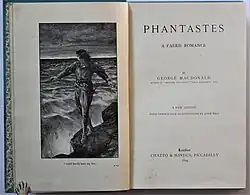

H. G. Wells's description of the subterranean Morlocks in his 1895 science fiction novel The Time Machine are suggestive of Gollum.[3] Parallels between The Hobbit and Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth include a hidden runic message and a celestial alignment that direct the adventurers to the goals of their quests.[18] Tolkien acknowledged MacDonald's 1858 fantasy Phantastes as a source in a letter. He wrote that MacDonald's sentient trees had "perhaps some remote influence" on his tree-giant Ents.[T 5]

A major influence was the Arts and Crafts polymath William Morris. Tolkien wished to imitate the style and content of Morris's medievalising prose and poetry romances such as the 1889 The House of the Wolfings,[T 6] and made use of placenames such as the Dead Marshes[T 7] and Mirkwood.[T 8] Tolkien read Morris's 1870 translation of the Völsunga saga when he was a student, introducing him to Norse mythology.[21] The medievalist Marjorie Burns writes that Bilbo Baggins's character and adventures in The Hobbit match Morris's account of his travels in Iceland in the early 1870s in numerous details. Like Bilbo's, Morris's party set off enjoyably into the wild on ponies. He meets a "boisterous" Beorn-like man called "Biorn the boaster" who lives in a hall beside Eyja-fell, and who tells Morris, tapping him on the belly, "... besides, you know you are so fat", just as Beorn pokes Bilbo "most disrespectfully" and compares him to a plump rabbit. Burns notes that Morris was "relatively short, a little rotund, and affectionately called 'Topsy', for his curly mop of hair", all somewhat Hobbit-like characteristics. Further, she writes, "Morris in Iceland often chooses to place himself in a comic light and to exaggerate his own ineptitude", just as Morris's companion, the painter Edward Burne-Jones, gently teased his friend by depicting him as very fat in his Iceland cartoons. Burns suggests that these images "make excellent models" for the Bilbo who runs puffing to the Green Dragon inn or "jogs along behind Gandalf and the dwarves" on his quest. Another definite resemblance is the emphasis on home comforts: Morris enjoyed a pipe, a bath, and "regular, well-cooked meals"; Morris looked as out of place in Iceland as Bilbo did "over the Edge of the Wild"; both are afraid of dark caves; and both grow through their adventures.[22]

In the 20th century, Lord Dunsany wrote fantasy novels and short stories that Tolkien read, without agreeing with Dunsany's irony, skepticism, or the use of dreams to explain fantasy away.[3] Further, Tolkien found Dunsany's creation of names inconsistent and unconvincing; Tolkien wrote that Middle-earth names were "coherent and consistent and made upon two related linguistic formulae [i.e. Quenya and Sindarin], so that they achieve a reality not fully achieved ... by other name-inventors (say Swift or Dunsany!)."[T 9] The fantasy author E. R. Eddison was influenced by Dunsany.[lower-alpha 1][24] His most famous work is the 1922 The Worm Ouroboros.[25][26] Tolkien had met Eddison and had read The Worm Ouroboros, praising it in print, but commenting in a letter that he disliked Eddison's philosophy, cruelty, and choice of names.[T 10]

David Lindsay's 1920 science fiction and fantasy novel A Voyage to Arcturus[27] was a central influence on C. S. Lewis's Space Trilogy,[28] and through him on Tolkien. Tolkien said he read the book "with avidity", finding it "more powerful and more mythical" than Lewis's 1938 Out of the Silent Planet, but less of a story.[T 11] On the other hand, Tolkien did not approve of the framing device that Lindsay had used, namely anti-gravity rays and a crystal torpedo ship; in his unfinished novel The Notion Club Papers, Tolkien makes one of the protagonists, Guildford, criticise those kinds of "contraptions".[3]

Frontispiece and title page of George MacDonald's 1858 Phantastes, illustrated by John Bell. The novel was one of the first fantasies for adults.

Frontispiece and title page of George MacDonald's 1858 Phantastes, illustrated by John Bell. The novel was one of the first fantasies for adults. A double-page spread in archaic style[29] in William Morris's 1896 novel The Well at the World's End, illustrated with woodcuts on vellum by his friend Edward Burne-Jones

A double-page spread in archaic style[29] in William Morris's 1896 novel The Well at the World's End, illustrated with woodcuts on vellum by his friend Edward Burne-Jones Bilbo's character and adventures match many details of William Morris's expedition in Iceland.[22] Cartoon of Morris riding a pony by his travelling companion Edward Burne-Jones (1870)

Bilbo's character and adventures match many details of William Morris's expedition in Iceland.[22] Cartoon of Morris riding a pony by his travelling companion Edward Burne-Jones (1870)

English literary traditions

.jpg.webp)

Charles Dickens' 1837 novel The Pickwick Papers has likewise been shown to have reflections in Tolkien.[30] Michael Martinez, writing for The Tolkien Society, finds "similar dialogue styles and character qualities" in Dickens and Tolkien, and "moments that elicit the same emotional resonance".[31] Martinez gives as examples the likeness of the Fellowship of the Ring's group of nine to Pickwick's group of friends, and of Bilbo's speech at his birthday party to Pickwick's first speech to his group.[31]

The scholar of English literature Anna Vaninskaya argues that the form and themes of Tolkien's early writings fit into the romantic tradition of writers like Morris and W. B. Yeats. In terms of politics, she compares Tolkien's mature writings with the romantic Little Englandism and anti-statism of 20th century writers like George Orwell and G. K. Chesterton.[32] Postwar literary figures such as Anthony Burgess, Edwin Muir and Philip Toynbee heavily criticized The Lord of the Rings, but others like the novelists Naomi Mitchison and Iris Murdoch respected the work, while the poet W. H. Auden championed it. Later critics have placed Tolkien closer to the modernist tradition with his emphasis on language and temporality, while his pastoral emphasis is shared with First World War poets and the Georgian movement. The Tolkien scholar Claire Buck suggests that if Tolkien was intending to create a new mythology for England, that would fit the tradition of English post-colonial literature and the many novelists and poets who reflected on the state of modern English society and the nature of Englishness.[2]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Eddison was an occasional member of the Inklings literary group, to which Tolkien and Lewis belonged.[23]

References

Primary

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, Tolkien's footnote to letter 306 to Michael Tolkien, 1967-8

- ↑ Tolkien 1937, p. 150

- ↑ Tolkien 1937, pp. 6–7

- ↑ Tolkien, J. R. R. Letter to L.M. Cutts of 26 October 1958, Sotheby's English Literature, History, Fine Bindings, Private Press Books, Children's Books, Illustrated Books and Drawings 10 July 2003 (Auction Catalogue), Sotheby's.

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #1 to Edith Bratt, October 1914

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #226 to L. W. Forster, December 1960

- ↑ Tolkien 1937, p. 183, note 10

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #19 to Stanley Unwin, 16 December 1937

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #199 to Caroline Everett, 24 June 1957

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #26 to Stanley Unwin, 4 March 1938

Secondary

- ↑ Shippey 2005, pp. 146–149.

- 1 2 Buck, Claire (2013) [2007]. "Literary Context, Twentieth Century". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 363–366. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Nelson, Dale (2013) [2007]. "Literary Influences, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 366–377. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- 1 2 3 Carpenter 1978, p. 168.

- 1 2 Hooker 2011, pp. 162–192.

- 1 2 Auden, W. H. (31 October 1954). "The Hero Is a Hobbit". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Shippey 2005, p. 393.

- ↑ Shippey 2001, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Resnick, Henry (1967). "An Interview with Tolkien". Niekas: 37–47.

- ↑ Nelson, Dale J. (2006). "Haggard's She: Burke's Sublime in a popular romance". Mythlore (Winter–Spring).

- 1 2 Flieger 2005, p. 150.

- ↑ Muir, Edwin (1988). The Truth of Imagination: Some Uncollected Reviews and Essays. Aberdeen University Press. p. 121. ISBN 0-08-036392-X.

- ↑ Lobdell 2004, pp. 5–6

- 1 2 3 4 Rogers, William N. II; Underwood, Michael R. (2000). "Gagool and Gollum: Exemplars of Degeneration in King Solomon's Mines and The Hobbit". In Sir George Clark (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien and His Literary Resonances: Views of Middle-earth. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 121–132. ISBN 978-0-313-30845-1.

- ↑ Hooker 2006, pp. 123–152 "Frodo Quatermain," "Tolkien and Haggard: Immortality," "Tolkien and Haggard: The Dead Marshes"

- 1 2 Lobdell 2004, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Lupoff, Richard A.; Stiles, Steve (2015). Edgar Rice Burroughs: Master of Adventure. London: Hachette UK. p. pt 135. ISBN 978-1-4732-0871-1. OCLC 932059522.

- 1 2 Hooker 2014, pp. 1–12.

- ↑ Gilliver, Peter; Marshall, Jeremy; Weiner, Edmund (23 July 2009). The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-19-956836-9.

- ↑ Flieger 1983, pp. 35–41.

- ↑ Carpenter, Humphrey (2000). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. Mariner Books. p. 77. ISBN 0-618-05702-1.

- 1 2 Burns, Marjorie (2005). Perilous Realms: Celtic and Norse in Tolkien's Middle-earth. University of Toronto Press. pp. 86–92. ISBN 978-0-8020-3806-7.

- ↑ "Web Resources". The Journal of Inklings Studies. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ↑ Olson, Danel (2010). 21st-Century Gothic: Great Gothic Novels Since 2000. Scarecrow Press. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-8108-7729-0.

- ↑ De Camp 1976, pp. 116, 132–133.

- ↑ Moorcock, Miéville & VanderMeer 2004, p. 47.

- ↑ Wolfe, Gary K. (1985). "David Lindsay". In Bleiler, E. F. (ed.). Supernatural Fiction Writers. Scribner's. pp. 541–548. ISBN 0-684-17808-7.

- ↑ Lindskoog, Kathryn. "A Voyage to Arcturus, C. S. Lewis, and The Dark Tower". Discovery.

- ↑ "The Well at the World's End". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ↑ Hooker 2006, pp. 117–122 "The Leaf Mold of Tolkien's Mind"

- 1 2 Martinez, Michael (10 July 2015). "Tolkien's Dickensian Dreams". The Tolkien Society. Retrieved 31 March 2023. A longer version of the article is Dickens' short story that inspired a Tolkien chapter.

- ↑ Lee 2020, Anna Vaninskaya, "Modernity: Tolkien and His Contemporaries", pages 350–366

Sources

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1978) [1977]. J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. Unwin Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-04928-039-7.

- De Camp, Lyon Sprague (1976). Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers. Arkham House. ISBN 978-0-87054-076-9.

- Flieger, Verlyn (1983). Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien's World. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-1955-9.

- Flieger, Verlyn (2005). Interrupted Music: The Making Of Tolkien's Mythology. Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-824-5.

- Hooker, Mark T. (2006). Tolkienian Mathomium: A Collection of Articles on J. R. R. Tolkien and his Legendarium. Llyfrawr. ISBN 978-1-4382-4631-4.

- Hooker, Mark T. (2011). "Reading John Buchan in Search of Tolkien". In Fisher, Jason (ed.). Tolkien and the Study of his Sources: Critical Essays. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6482-1. OCLC 731009810.

- Hooker, Mark T. (2014). The Tolkienaeum: Essays on J.R.R. Tolkien and his Legendarium. Llyfrawr. ISBN 978-1-49975-910-5.

- Lee, Stuart D., ed. (2020) [2014]. A Companion to J. R. R. Tolkien. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-119-65602-9.

- Lobdell, Jared C. (2004). The World of the Rings: Language, Religion, and Adventure in Tolkien. Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9569-4.

- Moorcock, Michael; Miéville, China; VanderMeer, Jeff (1 January 2004). Wizardry & Wild Romance. MonkeyBrain Books. ISBN 978-1-932265-07-1.

- Ordway, Holly (2021). Tolkien's Modern Reading: Middle-earth Beyond the Middle Ages. Word on Fire. ISBN 978-1-9432-4372-3.

- Shippey, Tom (2001) [2000]. J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261-10401-3.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). ISBN 978-0-261-10275-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). Douglas A. Anderson (ed.). The Annotated Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002). ISBN 978-0-618-13470-0.