The Grimaldi tower is one of two towers that stand next to the Saint-Esprit chapel and the old cathedral in Antibes, in the Alpes-Maritimes department, in France.

History

Since the building archives have been destroyed, the exact date of the construction of the tower cannot be established with certainty. It is known, however, that it was built shortly after the recapture of the region from the Saracens, so its construction may date from the 11th century.

This construction was therefore contemporaneous with the possession of the seigneury of Antibes by the Rodoald family. In the 10th century, Antibes was under constant threat of attack by the Saracens, who maintained a permanent fortified settlement near Fraxinetum, near Saint-Tropez. In about 974 (sources vary regarding the exact date), the Saracens were defeated and driven from Provence by William I of Provence, who subsequently rewarded the knights who fought by his side with gifts of conquered land.[1] [2][3] In about 975,[2] William gave what was, at the time, a modest fortified settlement to Rodoard, head of a branch of the powerful family of the house of Grasse.[4] Rodoald thereby became the Count of Antibes and fief of William, Count of Provence. Although, after the defeat, the Saracens maintained no permanent settlement in Provence, they continued to launch sporadic raids.[5] Rodoald and his family are thought to have been responsible for the construction of the tower for defensive purposes.

The seigniory of Antibes was given in 1275 to the bishop of Grasse. The Bishop of Grasse retained temporal jurisdiction until the time of Clement VII who, in 1383, transferred it, to the Grimaldi family for 9,000 florins. Although the Grimaldi family was already powerful elsewhere in the Mediterranean region, it only arrived in Antibes much later— about 1378.[2] Thus, although the tower carries the Grimaldi name, it was not built by them.

Description

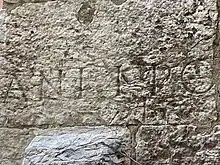

The Grimaldi tower is 30 meters high with a square section of 7.50 m per side. The thickness of the walls at the base is 2 meters. The exterior facing has 70 dressed stone courses whose thicknesses vary between 0.55 m and 0.30 m. Many of these stones were salvaged from Roman buildings and some have Roman inscriptions and appear to be elements of architraves or cornices.

The interior is divided into four floors, the upper three of which are approximately equal in height, and half as high as the ground floor. The ground floor communicates with the first floor only by a square hole and one could descend there only by a ladder.

The original access door to the tower, located on the north face, has been walled up. Its threshold was 0.60 m above the floor of the first floor, or 6 m above the ground. Thus, the tower could only be accessed by a sliding ladder. The current accesses are modern: there is one on the west facade at 1.40 m above the ground, and one on the east facade.

The second and third floors received daylight only through barbicans 0.80 m wide, on each side, placed 1 m above the floor. The openings on the third floor, which hold the bells, are modern.

The upper platform is supported by a vault. It is reached by a stone staircase.

The architecture of the tower suggests that its original purpose was to serve both as a watchtower and as a redoubt or stronghold in the event of a siege of the city.

The Grimaldi tower now serves as the bell tower of the Antibes Cathedral (French: Cathédrale Notre-Dame-de-l'Immaculée-Conception d'Antibes), which is located directly across the street.

Listing as Historic Monument

The Ministry of Culture listed the Grimaldi tower, together with the Cathedral and the adjoining chapel of the Holy Spirit, as a heritage monument by order of October 16, 1945.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ Edouard Baratier, Entre Francs et Arabes, in the collection Histoire de Provence. pg. 109.

- 1 2 3 Tisserand, Eugene (1876). Petite histoire d’Antibes des origines à la Revolution (in French) (Republication of original from 1876 ed.). EDR Édition des Régionalismes. pp. 68, 69. ISBN 9782824006093.

- ↑ Delaval, Éric; Thernot, directors of publication, Robert (2013). Aux originesd’Antibes, Antiquité et Haut Moyen Age (in French). Milan: Musée d’Archéologie, Antibes. p. 113. ISBN 9788836626854.

- ↑ Tisserand, Eugene (1876). Petite histoire d’Antibes des origines à la Révolution (in French). Éditions des Régionalismes. pp. 64–68, 80. ISBN 978-2-8240-0609-3.

- ↑ "Les Invasions: Le Second Assaut Contre L'europe Chrétienne VII<sup>e</sup>ȓXI<sup>e</sup> Siècles). By <italic>Lucien Musset</italic>. ["Nouvelle Clio": L'histoire et ses problèmes, Number 12<sup>bis</sup>.] (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. 1965. Pp. 297. 20 fr.)". The American Historical Review. January 1967. doi:10.1086/ahr/72.2.544. ISSN 1937-5239.

- ↑ "Eglise paroissiale, chapelle Saint-Esprit et tour Grimaldi". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 2023-01-27.