In logic, statistical inference, and supervised learning, transduction or transductive inference is reasoning from observed, specific (training) cases to specific (test) cases. In contrast, induction is reasoning from observed training cases to general rules, which are then applied to the test cases. The distinction is most interesting in cases where the predictions of the transductive model are not achievable by any inductive model. Note that this is caused by transductive inference on different test sets producing mutually inconsistent predictions.

Transduction was introduced by Vladimir Vapnik in the 1990s, motivated by his view that transduction is preferable to induction since, according to him, induction requires solving a more general problem (inferring a function) before solving a more specific problem (computing outputs for new cases): "When solving a problem of interest, do not solve a more general problem as an intermediate step. Try to get the answer that you really need but not a more general one."[1] A similar observation had been made earlier by Bertrand Russell: "we shall reach the conclusion that Socrates is mortal with a greater approach to certainty if we make our argument purely inductive than if we go by way of 'all men are mortal' and then use deduction" (Russell 1912, chap VII).

An example of learning which is not inductive would be in the case of binary classification, where the inputs tend to cluster in two groups. A large set of test inputs may help in finding the clusters, thus providing useful information about the classification labels. The same predictions would not be obtainable from a model which induces a function based only on the training cases. Some people may call this an example of the closely related semi-supervised learning, since Vapnik's motivation is quite different. An example of an algorithm in this category is the Transductive Support Vector Machine (TSVM).

A third possible motivation of transduction arises through the need to approximate. If exact inference is computationally prohibitive, one may at least try to make sure that the approximations are good at the test inputs. In this case, the test inputs could come from an arbitrary distribution (not necessarily related to the distribution of the training inputs), which wouldn't be allowed in semi-supervised learning. An example of an algorithm falling in this category is the Bayesian Committee Machine (BCM).

Example problem

The following example problem contrasts some of the unique properties of transduction against induction.

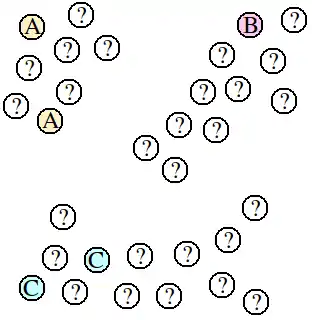

A collection of points is given, such that some of the points are labeled (A, B, or C), but most of the points are unlabeled (?). The goal is to predict appropriate labels for all of the unlabeled points.

The inductive approach to solving this problem is to use the labeled points to train a supervised learning algorithm, and then have it predict labels for all of the unlabeled points. With this problem, however, the supervised learning algorithm will only have five labeled points to use as a basis for building a predictive model. It will certainly struggle to build a model that captures the structure of this data. For example, if a nearest-neighbor algorithm is used, then the points near the middle will be labeled "A" or "C", even though it is apparent that they belong to the same cluster as the point labeled "B".

Transduction has the advantage of being able to consider all of the points, not just the labeled points, while performing the labeling task. In this case, transductive algorithms would label the unlabeled points according to the clusters to which they naturally belong. The points in the middle, therefore, would most likely be labeled "B", because they are packed very close to that cluster.

An advantage of transduction is that it may be able to make better predictions with fewer labeled points, because it uses the natural breaks found in the unlabeled points. One disadvantage of transduction is that it builds no predictive model. If a previously unknown point is added to the set, the entire transductive algorithm would need to be repeated with all of the points in order to predict a label. This can be computationally expensive if the data is made available incrementally in a stream. Further, this might cause the predictions of some of the old points to change (which may be good or bad, depending on the application). A supervised learning algorithm, on the other hand, can label new points instantly, with very little computational cost.

Transduction algorithms

Transduction algorithms can be broadly divided into two categories: those that seek to assign discrete labels to unlabeled points, and those that seek to regress continuous labels for unlabeled points. Algorithms that seek to predict discrete labels tend to be derived by adding partial supervision to a clustering algorithm. Two classes of algorithms can be used: flat clustering and hierarchical clustering. The latter can be further subdivided into two categories: those that cluster by partitioning, and those that cluster by agglomerating. Algorithms that seek to predict continuous labels tend to be derived by adding partial supervision to a manifold learning algorithm.

Partitioning transduction

Partitioning transduction can be thought of as top-down transduction. It is a semi-supervised extension of partition-based clustering. It is typically performed as follows:

Consider the set of all points to be one large partition. While any partition P contains two points with conflicting labels: Partition P into smaller partitions. For each partition P: Assign the same label to all of the points in P.

Of course, any reasonable partitioning technique could be used with this algorithm. Max flow min cut partitioning schemes are very popular for this purpose.

Agglomerative transduction

Agglomerative transduction can be thought of as bottom-up transduction. It is a semi-supervised extension of agglomerative clustering. It is typically performed as follows:

Compute the pair-wise distances, D, between all the points.

Sort D in ascending order.

Consider each point to be a cluster of size 1.

For each pair of points {a,b} in D:

If (a is unlabeled) or (b is unlabeled) or (a and b have the same label)

Merge the two clusters that contain a and b.

Label all points in the merged cluster with the same label.

Manifold transduction

Manifold-learning-based transduction is still a very young field of research.

See also

References

- ↑ Vapnik, Vladimir (2006). "Estimation of Dependences Based on Empirical Data". Information Science and Statistics: 477. doi:10.1007/0-387-34239-7. ISSN 1613-9011.

- V. N. Vapnik. Statistical learning theory. New York: Wiley, 1998. (See pages 339-371)

- V. Tresp. A Bayesian committee machine, Neural Computation, 12, 2000, pdf.

- B. Russell. The Problems of Philosophy, Home University Library, 1912. .

External links

- A Gammerman, V. Vovk, V. Vapnik (1998). "Learning by Transduction." An early explanation of transductive learning.

- "A Discussion of Semi-Supervised Learning and Transduction," Chapter 25 of Semi-Supervised Learning, Olivier Chapelle, Bernhard Schölkopf and Alexander Zien, eds. (2006). MIT Press. A discussion of the difference between SSL and transduction.

- Waffles is an open source C++ library of machine learning algorithms, including transduction algorithms, also Waffles.

- SVMlight is a general purpose SVM package that includes the transductive SVM option.