Trente et Quarante (Thirty and Forty), also called Rouge et Noir (Red and Black), is a 17th-century gambling card game of French origin played with cards and a special table.[1] It is rarely found in US casinos,[2] but still very popular in Continental European casinos, especially in France, Italy, and Monaco. It is a simple game that usually gives the players a very good expected return of more than 98%.[3]

History

Trente et Quarante is recorded as early as 1694 in a French dictionary that simple says it is a "type of card game".[4] By the mid-18th century it had reached England, Lyonell Vane recording that he played it alongside Quadrille and Basset,[5] and its rules are recorded in an English Hoyle in 1796.[6]

The game also reached Germany and was played in 18th-century Holstein in northern Germany under the Low German dialect name of Dör den Hund ("Through the Dog"), because, having been introduced by French migrants, many inexperienced players "went to the dogs" i.e. were ruined by playing it.[7][8]

Rules

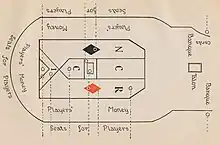

Two croupiers sit on each side of the table, one of them being the dealer; behind the two on the side opposite to the dealer a supervisor of the game has his seat. Six packs of fifty-two cards each are used; these are well shuffled, and the croupier asks any of the players to cut, handing him a blank card with which to divide the mixed packs. The game consists of the dealer dealing two rows of cards face up, the first (upper) row called noir and the second (lower) row called rouge. There are only four bets in trente et quarante: rouge and noir, known as the grand tableau, and couleur and inverse, known as the petit tableau.[9] Rouge and noir bets are concerned with which row wins, and the couleur and inverse bets with whether the first card in the winning row is the same (couleur) or opposite (inverse) to the color of the row.

Aces are worth 1 point, court cards 10 and pip cards their face value.[10] A tie is a stand-off, and on a 31-point tie, players may double or quit on the next coup or immediately lose half their stake.[11] The winning total will range between 30 and 40 card points, which is from where the name of the game derives.[12]

Winning row

Cards for each row are dealt until its total exceeds thirty (trente). The row whose total is closest to thirty is the winning row. If, for example, the cards dealt in the first row were 8, 7, K, and 9 and those in the second row were A, 2, J, Q, and 10 the noir total would be 34 and the rouge total would be 33, so that rouge would win. If the color of the first card in the rouge row also were red (in this example an ace of diamonds or hearts), the couleur bet also would win and the dealer will announce "Rouge gagne et la couleur." However, if the first card dealt were black (an ace of clubs or spades), the dealer announces "Rouge gagne et la couleur perd." Indeed the dealer always announces, in French, the winning or losing of rouge and colour, as follows:

- Rouge gagne et la couleur (Rouge and Colour win);

- Rouge gagne et la couleur perd (Rouge and Inverse win);

- Rouge perd et la couleur gagne (Noir and Colour win);

- Rouge perd et la couleur (Noir and Inverse win).

It frequently happens that both rows of cards when added together give the same number. Should they both, for instance, add up to thirty-three, the dealer will announce "Trois après," and the deal goes for nothing except in the event of their adding up to thirty-one.[13][9]

Refait

Un apres (i.e. thirty-one) is known as a refait; the stakes are put in prison to be left for the decision of the next deal, or if the player prefers it he can withdraw half his stake, leaving the other half for the bank. Assurance against a refait can be made by paying 1% on the value of the stake with a minimum of five francs. When thus insured against a refait the player is at liberty to withdraw his whole stake. It has been calculated that on an average a refait occurs once in thirty-eight coups.[9] Refaits are the source of the sole house advantage in the game.

After each deal the cards are pushed into a metal bowl let into the table in front of the dealer. When he has not enough left to complete the two rows, he remarks "Les cartes passent" (The cards pass); they are taken from the bowl, reshuffled, and another deal begins.[9]

References

- ↑ Parlett, David (2008). The Penguin Book of Card Games. London: Penguin Books. p. 604.

- ↑ Harold L. Vogel, Travel industry economics: a guide for financial analysis pg. 206 Cambridge University Press (2001) ISBN 0-521-78163-9

- ↑ William Norman Thompson Gambling in America: an encyclopedia of history, issues, and society pg. 379 ABC-CLIO (2001) ISBN 1-57607-159-6

- ↑ Le Dictionnaire de L'Académie Françoise (1694), p. 600.

- ↑ Vane (1754), pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Jones (1796), pp. 285–288.

- ↑ Lehman & Handelmann (1858), p. 259.

- ↑ Schütze (1801), p. 172.

- 1 2 3 4 Chisholm (1911), p. 251.

- ↑ Gayle Mitchell Easy Casino Gambling: Winning Strategies for the Beginner pg. 213 Skyhorse Publishing (2007) ISBN 1-60239-011-8

- ↑ David Parlett, The Oxford Dictionary of card games, pg. 311 Oxford University Press (1996) ISBN 0-19-869173-4

- ↑ Diagram Group The Little Giant Encyclopedia of Card Games pg. 348 Sterling (1995) ISBN 0-8069-1330-4

- ↑ Jean Boussac. The Trente-et-Quarante or the Red and Black, Paris, 1896. Transl. from French, 2017.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Trente et Quarante". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 251.

Bibliography

- _ (1694). Le Dictionnaire de L'Académie Françoise. Vol. 2 (M–Z). Paris: Coignard.

- Chisholm, Hugh (1911). The Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27. Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

- Jones, Charles (1796). Hoyle's Games Improved. London: Baldwin et al.

- Lehmann, Th. and Dr Handelmann (1858). Jahrbücher für die Landeskunde, Volume 12. Kiel: Akademische Buchhandlung.

- Schick, Louis (1864). Elemental Instruction to Play Trente-et-quarante and Roulette. Homburg: Louis Schick.

- Schütze, Johann Friedrich (1800). Holsteinisches Idiotikon. Hamburg: Heinrich Ludwig Villaume.

- Vane, Lyonell (1754). Letters to a Gentleman of Fortune, Relating to His Conduct in Life. London: Owen.