| United States v. Susan B. Anthony | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | U.S. District Court for the Northern District of New York and the U.S. Circuit Court for the Northern District of New York |

| Full case name | United States v. Susan B. Anthony |

| Argued | June 17, 1873 |

| Holding | |

| Susan B. Anthony was found guilty of violating the Enforcement Act of 1870 and New York law by illegally voting, and fined $100. The right to a jury trial exists only when there is a disputed fact, not when there is an issue of law. | |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Justice Ward Hunt |

| Laws applied | |

| Enforcement Act of 1870, U.S. Const. amend. XIV | |

Superseded by | |

| Sparf v. United States (1895) | |

United States v. Susan B. Anthony was the criminal trial of Susan B. Anthony in a U.S. federal court in 1873. The defendant was a leader of the women's suffrage movement who was arrested for voting in Rochester, New York in the 1872 elections in violation of state laws that allowed only men to vote. Anthony argued that she had the right to vote because of the recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, part of which reads, "No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States."

The judge, Ward Hunt, was a recently appointed U.S. Supreme Court Justice who had responsibility for the federal circuit court in which the trial was held. He did not allow the jurors to discuss this case but instead directed them to find Anthony guilty. On the final day of the trial, Hunt asked Anthony if she had anything to say. Anthony, who had not previously been permitted to speak, responded with what one historian of the women's movement has called "the most famous speech in the history of the agitation for woman suffrage".[1] Repeatedly ignoring the judge's order to stop talking and sit down, she protested what she called "this high-handed outrage upon my citizen's rights".[2] She also protested the injustice of denying women the right to vote. When Justice Hunt sentenced Anthony to pay a fine of $100, she defiantly said that she would never do so. Hunt then announced that Anthony would not be jailed for failure to pay the fine, a move that had the effect of preventing her from taking her case to the Supreme Court.

Fourteen other Rochester women who lived in Anthony's ward also voted in that election and were arrested, but the government never took them to trial. The election inspectors who allowed the women to vote were arrested, tried and found guilty. They were pardoned by President Ulysses S. Grant after being jailed for refusing to pay the fines imposed by the court.

The trial, which was closely followed by the national press, helped make women's suffrage a national issue. It was a major step in the transition of the women's rights movement from one that encompassed a number of issues into one that focused primarily on women's suffrage. Judge Hunt's directed verdict created a controversy within the legal community that lasted for years. In 1895, the Supreme Court ruled that a federal judge could not direct a jury to return a guilty verdict in a criminal trial.

Background

Early demands for women's suffrage

The demand for women's suffrage grew out of the broader movement for women's rights, which began to emerge in the U.S. in the early 1800s. There was little demand for the right to vote in the movement's early days, when the focus was on such issues as the right of women to speak in public settings and on property rights for married women. At the first women's rights convention, the Seneca Falls Convention held in western New York in 1848, the only resolution that did not pass unanimously was the one that called for women's suffrage. Originated by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was just beginning her career as a suffrage leader, the resolution was adopted only after Frederick Douglass, an abolitionist leader and a former slave, gave it his strong support.[3] That convention helped to popularize the idea of women suffrage, and by the time of the first National Women's Rights Convention in 1850, suffrage was becoming a generally accepted part of the movement's goals.[4]

Women began to attempt to vote. In Vineland, New Jersey, a center for radical spiritualists, nearly 200 women placed their ballots into a separate box and attempted to have them counted during the 1868 elections, but without success. Lucy Stone, a leader of the women's rights movement who lived nearby, attempted to vote soon afterwards, also without success.[5]

New Departure strategy

In 1869, Francis and Virginia Minor, husband and wife suffragists from Missouri, developed a strategy that became known as the New Departure, which engaged the suffrage movement for several years. This strategy was based on the belief that the recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, together with the pending Fifteenth Amendment, implicitly enfranchised women. The primary purpose of these amendments was to establish the newly freed slaves as citizens with voting rights. In the process of doing so, these amendments defined citizenship in a way that clearly included women, prohibited the states from abridging "the privileges or immunities of citizens", and transferred partial control over voting rights from the state to the federal level. The Minors cited Corfield v. Coryell, a case in 1823 in which a federal circuit court ruled that voting rights were included in the privileges and immunities of citizens. They also cited the preamble to the Constitution to support their assertion that the basic rights of citizens were natural rights that provided the foundation for constitutional authority. According to the New Departure strategy, the main task of the suffrage movement was to establish through court action that these principles taken together implied that women had the right to vote.[6]

In 1871 Victoria Woodhull, a stockbroker with little previous connection to the women's movement, presented a modified version of the New Departure strategy to a committee of Congress. Instead of asking the courts to rule that the Constitution implicitly enfranchised women, she asked Congress to pass a declaratory act to accomplish the same goal. The committee rejected her proposal.[7]

In early 1871, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) officially adopted the New Departure strategy. It encouraged women to attempt to vote and to file federal lawsuits if denied that right.[8] The NWSA, organized by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1869, was the first national women's rights organization. A rival organization called the American Woman Suffrage Association, which was created a few months later, did not adopt the New Departure strategy but instead campaigned for state laws that would enable women to vote.[9]

Soon hundreds of women attempted to vote in dozens of localities.[10] Accompanied by Frederick Douglass, an abolitionist leader and a supporter of women's rights, sixty-four women unsuccessfully tried to register in Washington, D.C. in the spring of 1871, and more than seventy attempted to vote.[11] In November 1871, the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia ruled against lawsuits brought by these women. It ruled that citizenship did not imply the right to vote, saying that "the legal vindication of the natural right of all citizens to vote would, at this stage of popular intelligence, involve the destruction of civil government" and that "The fact that the practical working of the assumed right would be destructive of civilization is decisive that the right does not exist."[12]

Arrest and conviction for voting

Vote in 1872 election

The reaction of the authorities was muted in these unsuccessful attempts to vote. The reaction was sharply different when Susan B. Anthony succeeded in voting in the presidential election of 1872 in Rochester, New York. Anthony was a nationally known figure. She and Stanton had founded the Women's Loyal National League, the first national women's political organization in the U.S., in 1863 during the American Civil War. Anthony was the chief organizer of the League's petition drive against slavery, which collected nearly 400,000 signatures in the largest petition drive in U.S. history up to that time.[13][14] She and Stanton were the leaders of National Woman Suffrage Association. At the time when she cast her ballot, Anthony was the nation's best-known advocate of the right of women to vote.[15]

_from_Monroe_County_Library.jpg.webp)

On November 1, 1872, Anthony walked with her sisters Guelma, Hannah, and Mary to a voter registration office in a nearby barber shop and demanded to be registered. Anthony quoted the Fourteenth Amendment to the election inspectors to justify their demand and threatened to sue the inspectors personally if they refused. The inspectors consulted a prominent local lawyer, John Van Voorhis (a strong supporter of women's suffrage), who advised them to register the women after they took the standard oaths of registry, which, he said, "would put the entire onus of the affair on them".[16]

A skilled publicist, Anthony then went to a newspaper office to provide an interview about what had just happened.[17] News of the women's registration appeared in the afternoon newspapers, with some of them calling for the arrest of the inspectors who had registered the women. Anthony returned to the voter registration office to ask the inspectors to stand firm and to assure them that she would cover any legal costs they might incur. Other women in Rochester began to register, bringing the total to nearly fifty.[18]

On election day, November 5, Anthony and fourteen other women from her ward went to the polling place to cast their ballots. Sylvester Lewis, a poll watcher, challenged their right to vote, thereby triggering a requirement that they take an oath stating that they were qualified to vote, which they did. The election inspectors were now in a difficult position. They were at risk of violating state law if they turned the women away because state law did not give them the authority to refuse the ballot to anyone who took the required oath. Federal law, however, made it illegal to receive the ballot of an ineligible voter. Moreover, federal law prescribed the same punishments for accepting the ballot of an ineligible voter as for refusing the ballot of an eligible voter. The inspectors decided to allow the women to vote.[19] The negative publicity of the previous days had influenced the officials in the other wards, who turned the other registered women away.[18]

Arrest

Anthony had not expected to vote, according to Ann D. Gordon, a historian of the women's movement. Instead, she had expected to be turned away from the polls, after which she planned to file a suit in federal court in pursuit of her right to vote. She didn't expect to be arrested either.[20]

On November 14, warrants for the arrest of the women who had voted and the election inspectors who had allowed them to do so were drawn up and shown to the press. William C. Storrs, one of the commissioners for the U.S. Circuit Court for the Rochester area, sent word to Anthony asking her to meet him in his office. Anthony replied that she "had no social acquaintance with him and didn't wish to call on him".[21]

On November 18, a deputy U.S. Marshal came to her house and said that Commissioner Storrs wished to see her in his office. When Anthony asked why, the officer replied that Storrs wanted to arrest her. Anthony said that men weren't arrested that way and demanded to be arrested properly. The deputy then produced the warrant and arrested her. Told that she was required to go with him, Anthony replied that she wasn't prepared to go immediately. The deputy said he would go on ahead, and she could follow when she was ready. Anthony said she would refuse to take herself to court, so the deputy waited while she changed her dress. Anthony then held out her wrists to be handcuffed, but the officer declined, saying he did not think that would be necessary.[18][21]

The other fourteen women who had voted and were subsequently arrested were: Charlotte ("Lottie") B. Anthony, Mary S. Anthony, Ellen S. Baker, Nancy M. Chapman, Hannah M. Chatfield, Jane M. Cogswell, Rhoda DeGarmo, Mary S. Hebard, Susan M. Hough, Margaret Garrigues Leyden, Guelma Anthony McLean, Hannah Anthony Mosher, Mary E. Pulver, and Sarah Cole Truesdale. The election inspectors who had allowed them to vote were arrested also. Their names were Beverly Waugh Jones, Edwin T. Marsh and William B. Hall.[22] Several of the women were involved in various types of reform activity. DeGarmo had been the recording secretary for the Rochester Women's Rights Convention of 1848, the second such convention in the country, held two weeks after the Seneca Falls Convention.[23]

As her attorney, Anthony chose Henry R. Selden, a respected local lawyer who had previously served as lieutenant governor of New York and as a judge on the New York Court of Appeals. The New York Commercial Advertiser said that Anthony's trial had taken on new importance now that Selden had agreed to take her case, and it suggested that men might need to reconsider their opinion on women's suffrage. Anthony also frequently consulted the lawyer for the election inspectors, John Van Voorhis, who had previously served as Rochester City Attorney.[24]

The women who were arrested were held to $500 bail. Everyone posted bail except Anthony, who refused.[25] Storrs issued a commitment authorizing the U.S. marshal to place her in the Albany County jail, but she was never actually held there.[26]

Pre-trial speaking tour

Anthony's arrest generated national news, which she turned into an opportunity to generate publicity for the suffrage movement. She spoke in 29 towns and villages of Monroe County, New York, where her trial was to be held and which would provide the jurors for her trial. Her speech was entitled "Is it a Crime for a U.S. Citizen to Vote?"[27] She said the Fourteenth Amendment gave her that right, proclaiming, "We no longer petition Legislature or Congress to give us the right to vote. We appeal to women everywhere to exercise their too long neglected 'citizen's right to vote'".[28] She quoted to her audiences the first section of the recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment, which reads:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Anthony then argued that,

The only question left to be settled now, is: Are women persons? And I hardly believe any of our opponents will have the hardihood to say they are not. Being persons, then, women are citizens; and no State has a right to make any new law, or to enforce any old law, that shall abridge their privileges or immunities."[29]

Her speech was printed in its entirety in one of the Rochester daily newspapers, which further spread her message to potential jurors.[30]

She drew attention to the inconsistent way that gendered words were used in the law. She pointed out that the New York tax laws referred only to "he", "him" and "his", yet taxes were collected from women. The federal Enforcement Act of 1870, which she was accused of violating, similarly used male pronouns only. Her official record of commitment was written with masculine pronouns, but the Clerk of the Court had inserted an "s" above "he" in the printed form to make it into "she", and similarly had altered to "his" to "her". She said, "I insist if government officials may thus manipulate the pronouns to tax, fine, imprison and hang women, women may take the same liberty with them to secure to themselves their right to a voice in the government."[31]

Other pre-trial activity

On January 21, 1873, at a hearing before the U.S. District Court in Albany, the capital of New York state, Selden presented detailed arguments in support of Anthony's case. He said the question of the right of women to vote had not been settled in the courts and therefore the government had no basis for holding Anthony as a criminal defendant. Without giving U.S. Attorney Richard Crowley a chance to make the government's case, Judge Nathan K. Hall ruled that Anthony would remain in custody.[32]

Anthony published Selden's arguments before this court as a pamphlet and distributed 3000 copies, some of which she mailed to newspaper editors in several states with requests to reprint them.[33] In the letter that accompanied her request to the publisher of the Rochester Evening Express, she asked for help in convincing people that her vote was not a crime, saying, "We must get the men of Rochester so enlightened that no jury of twelve can be found to convict us."[34]

On January 24, Crowley presented the proposed indictments to the grand jury at the District Court in Albany, which indicted the women voters. Anthony again pleaded not guilty and was held on bail for $1000. Selden posted Anthony's bail over her protest.[30][35]

On March 4, Anthony voted once again at an election in Rochester. This time, however, she was the only woman to do so.[35]

At an arraignment on May 22, Crowley requested the transfer of the case from the federal district court to the federal circuit court for the Northern New York District, which had concurrent jurisdiction. A session of this circuit court would meet in June in Canandaigua, the county seat of Ontario County, which borders on Monroe County. No reason for the move was given, but observers noted that U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ward Hunt was assigned to that circuit and would be available in June to try the case. Federal circuit courts often held important cases until the arrival of the assigned Supreme Court justice, whose participation would give the verdict greater weight.[30] The transfer also meant that jurors would not be drawn from Monroe County, which Anthony had thoroughly covered with her recent speaking tour on women's right to vote.[36] Anthony responded by speaking throughout Ontario County before the trial began with the assistance of her colleague Matilda Joslyn Gage.[33]

Trial

The trial had several complications. Anthony was accused of violating a state law that prohibited women from voting, but she was not tried in a state court. Instead she was tried in federal courts for violating the Enforcement Act of 1870, which made it a federal crime to vote in congressional elections if the voter was not qualified to vote under state law.[37] Her case was handled by two overlapping arms of the federal court system: the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of New York and the U.S. Circuit Court for the Northern District of New York. (This circuit court system was abolished in 1912.)

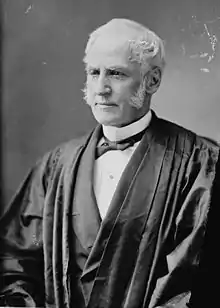

Justice Ward Hunt, who had recently been appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court, had responsibility for that circuit and was the judge in this trial. Hunt had never served as a trial judge. Originally a politician, he had begun his judicial career by being elected to the New York Court of Appeals.[38]

The trial, United States v. Susan B. Anthony, began on June 17, 1873, in Canandaigua, New York, and was closely followed by the national press. The case was being viewed as having some farcical aspects, and the press was ready for more. The New York Times reported that, "It was conceded that the defendant was, on the 5th November, 1872, a woman."[39]

Justice Hunt presided alone, which was contrary to established practice. Federal criminal trials at that time normally had two judges, and a case could not be forwarded to the Supreme Court unless the judges disagreed about the verdict. District Court Judge Nathan K. Hall, who had already been involved with Anthony's case in earlier court actions, served beside Judge Hunt during trials earlier that day, and he was on the bench with Hunt when Anthony's case was called. He did not remain there during Anthony's trial, however, but instead sat in the audience.[40] Also in the audience was former president Millard Fillmore.[41]

Legal arguments

The right of voting, or the privilege of voting, is a right or privilege arising under the constitution of the state, and not under the constitution of the United States. ... If the state of New York should provide that no person should vote until he had reached the age of thirty years, or after he had reached the age of fifty, or that no person having gray hair, or who had not the use of all his limbs, should be entitled to vote, I do not see how it could be held to be a violation of any right derived or held under the constitution of the United States. ...

If the fifteenth amendment had contained the word ‘sex,’ the argument of the defendant would have been potent. ... The amendment, however, does not contain that word. It is limited to race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Arguing for the defense, Selden said the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment made it clear that women were citizens and that states were prohibited from making laws that abridge "the privileges and immunities of citizens". Therefore, he said, women were entitled to all the rights of citizens, including the right to vote, the right that gives meaning to the other political rights. He cited examples of wrongs suffered by women in cultures all over the world partly because they had no voice in government. He said that Anthony voted in the sincere belief that she was voting legally and therefore could not be accused of knowingly violating a law.[44]

Arguing for the prosecution, Crowley said the "privileges and immunities" protected by the Fourteenth Amendment applied only to such rights as life, liberty and property, not the right to vote. He said that children were citizens, but no one would claim they had the right to vote. He cited recent state and federal court decisions that had upheld the right of states to restrict suffrage to males. He pointed out that the second section of the Fourteenth Amendment specifically referred to male voters when it stipulated reduced representation in Congress for states that restricted male suffrage.[45]

Through her attorney, Anthony requested permission to testify on her own behalf, but Hunt denied her request. Instead he followed a rule of common law at that time which prevented criminal defendants in federal courts from testifying.[46]

Directed verdict

After both sides had presented their cases on the second day of the trial, Justice Hunt delivered his written opinion. He had written it beforehand, he said, to ensure that, "there would be no misapprehension about my views".[47] He said the Constitution allowed states to prohibit women from voting and that Anthony was guilty of violating a New York law to that effect. He cited the Slaughter-House Cases and Bradwell v. Illinois, Supreme Court rulings made only weeks earlier that had narrowly defined the rights of U.S. citizenship. Furthermore, he said, the right to a trial by jury exists only when there is a disputed fact, not when there is an issue of law. In the most controversial aspect of the trial, Hunt ruled that the defense had conceded the facts of the case, and he directed the jury to deliver a guilty verdict. He denied Selden's request to poll the jury to get their opinions on what the verdict should be.[48] These moves were controversial because the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution begins with the words, "In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury".

N. E. H. Hull, a law professor who wrote a book-length study of this trial, commented on Justice Hunt's delivery of an opinion that Hunt said he had prepared earlier. Hull said, "Whether that meant he had written out his opinion before the trial commenced or whether he waited to hear if any arguments or evidence on that first day might influence his decision, one will never know."[49] After the trial, Anthony was outspoken in her belief that Hunt had written his verdict before the trial had begun. Van Voorhis, an attorney who had assisted Anthony, agreed, saying that Hunt had, "unquestionably prepared his opinion beforehand".[50]

The participants later voiced disagreement about what the jury's verdict would have been had there not been a directed verdict. U.S. Attorney Crowley said the jury had informally agreed to Hunt's verdict.[51] Anthony told a different story. The History of Woman Suffrage, which she co-edited, reported that one of the jurors said, "The verdict of guilty would not have been mine, could I have spoken, nor should I have been alone. There were others who thought as I did, but we could not speak."[52]

Anthony's speech to the court

impossibility of jury by her peers

All of my prosecutors—from the 8th ward corner grocery politician, who entered the complaint, to the United States Marshal, Commissioner, District Attorney, District Judge, your honor on the bench—not one is my peer, but each and all are my political sovereigns;

and had your honor submitted my case to the jury, as was clearly your duty, even then I should have had just cause of protest for not one of those men was my peer; but, native or foreign born, white or black, rich or poor, educated or ignorant, awake or asleep, sober or drunk, each and every man of them was my political superior; hence, in no sense, my peer.

Anthony's address to court after directed verdict[2]

On the second day and final day of the trial, in what is ordinarily a routine move, Hunt asked Anthony if she had anything to say. She responded with "the most famous speech in the history of the agitation for woman suffrage", according to Ann D. Gordon, a historian of the women's movement.[53]

Repeatedly ignoring the judge's order to stop talking and sit down, Anthony protested what she called "this high-handed outrage upon my citizen's rights", saying "you have trampled under foot every vital principle of our government. My natural rights, my civil rights, my political rights, my judicial rights, are all alike ignored."[2] She castigated Justice Hunt for denying her a trial by jury. She also declared that even if he had allowed the jury to discuss the case, she still would have been denied her right to a trial by a jury of her peers because women were not allowed to be jurors. She said that in the same way that slaves obtained their freedom by taking it "over, or under, or through the unjust forms of law", now for women to get their right to a voice in government, they must "take it; as I have taken mine, and mean to take it at every possible opportunity."[2]

Blocked path to Supreme Court

When Justice Hunt sentenced Anthony to pay a fine of $100, she responded, "I shall never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty"[54] and she never did. If Hunt had ordered her to be jailed until she paid the fine, Anthony could have filed a writ of habeas corpus to gain a hearing before the Supreme Court. Hunt instead announced he would not order her taken into custody, closing off that legal avenue. Because appeals to the Supreme Court in criminal court cases were not permitted at that time, Anthony was blocked from taking her case any further.[55]

Attempt to collect Anthony's fine

A month after the trial, a deputy federal marshal was dispatched to collect Anthony's fine. He reported that a careful search had failed to find any property that could be seized to pay the fine. The court took no further action.[56]

Peripheral legal action

Election inspectors' trial

The trial of the election inspectors who had allowed Anthony and the other fourteen women to vote was held immediately after Anthony's trial. The inspectors were found guilty of violating the Enforcement Act of 1870 and fined. They refused to pay their fines and were eventually jailed.[56]

There was public sympathy for the inspectors, who had been in a no-win situation, facing adverse legal action if they allowed the women to vote and also if they turned them away. The Rochester Evening Express said on February 26, 1874, "The arrest and imprisonment in our city jail of the Election Inspectors who received the votes of Susan B. Anthony and the other ladies, at the polls of the Eight Ward, some months ago, is a petty but malicious act of tyranny."[57] The jailed inspectors received food, coffee and a steady stream of visits from their supporters, including the women whom they allowed to vote. Anthony appealed to her friends in Congress for their release, and they in turn appealed to President Ulysses S. Grant, who pardoned the men on March 3, 1874. The inspectors were reelected to their offices in elections that were held on that same day.[58]

Women voter codefendants

The fourteen women who had been arrested with Anthony were indicted in January, 1873. On May 22, they were released on their own recognizance after U.S. Attorney Crowley announced that Anthony's case would be made into a test case. They were informed that they did not need to appear at Anthony's upcoming trial. On June 21, 1873, after Anthony's trial, the prosecutor entered motions of nolle prosequi in the circuit court to signal that the government would not pursue their case any further.[59]

Press coverage

The Associated Press provided daily reports of the trial that were printed in newspapers across the country. In some cases, newspapers filled several columns with the arguments prepared by the lawyers and with the judge's rulings. Some newspapers were harshly critical of the women voters. The Rochester Union and Advertiser said their action, "goes to show the progress of female lawlessness instead of the principle of female suffrage" and that "the efforts of Susan B. Anthony & Co. to unsex themselves and vote as men will be so far as they are successful both criminal and ridiculous."[60] The primary topic of interest was Judge Hunt's refusal to allow the jury to deliberate and vote on a verdict. The New York Sun called for Hunt's impeachment, saying that he had overthrown civil liberty.[61] The Trenton State Sentinel and Capital asked, "Why have juries at all if Judges can find verdicts—or direct them to be found, and then refuse to poll the jury?"[62]

Shortly before the trial began, the New York Daily Graphic ran a full-page caricature of Anthony on its front cover with the title "The Woman Who Dared". It depicted Anthony with a grim expression and wearing men's boots with spurs. In the background was a woman in a police uniform and men carrying groceries and babies. The accompanying story said that if Anthony were acquitted at the trial, the world would come to resemble the cartoon, and women would "acknowledge in the person of Miss Anthony the pioneer who first pursued the way they sought".[63]

Aftermath

Petition for remission of fine

In January 1874, Anthony petitioned Congress to remit her fine on the grounds that Judge Hunt's ruling had been unjust. The judiciary committees of both the Senate and the House debated the question. Senator Matthew Carpenter condemned Justice Hunt's ruling, saying that it was "altogether a departure from, and a most dangerous innovation upon, the well-settled method of jury-trial in criminal cases. Such a doctrine renders the trial by jury a farce. [Anthony] had no jury-trial, within the meaning of the Constitution, and her conviction was, therefore, erroneous."[58] Benjamin Butler brought a bill to remit Anthony's fine to the floor of the House, but it did not pass.[58]

Effect on the women's movement

The trial of Susan B. Anthony helped make women's suffrage a national issue. It was a major step in the transition of the women's rights movement from one that encompassed a number of issues into one that focused primarily on women's suffrage.[64]

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) continued to pursue the New Departure strategy even though Anthony had been blocked in her attempt to bring her voting rights case before the Supreme Court. Virginia Minor, one of the originators of the New Departure strategy, succeeded in that effort. When Minor was prevented from registering to vote in Missouri in 1872, she took her case first to a state circuit court, then to the Supreme Court of Missouri, and finally to the U.S. Supreme Court. Unfortunately for the suffrage movement, in 1875 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Minor v. Happersett that the Constitution did not implicitly support women's suffrage, stating that "the Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon anyone".[65]

The Happersett decision put an end to the New Departure strategy of trying to achieve women's suffrage through the courts. The NWSA decided to pursue the far more difficult strategy of campaigning for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would ensure voting rights for women. That struggle lasted for 45 years, until the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified in 1920. Supreme Court rulings did not establish the connection between citizenship and voting rights until the mid-twentieth century, with such decisions as Reynolds v. Sims and Wesberry v. Sanders, both in 1964.[65]

Continuing debate over directed verdicts

The controversy within the legal community over Justice Hunt's directed verdict continued for years. In 1882, a month after Justice Hunt's retirement from the Supreme Court, a circuit court judge ruled that it was wrong for a judge to direct a jury to deliver a verdict of guilty. In 1895, in Sparf v. United States, the Supreme Court ruled that a federal judge could not direct a jury to return a guilty verdict in a criminal trial.[65]

Other outcomes

In April 1874, Anthony published a book of more than 200 pages called An Account of the Proceedings on the Trial of Susan B. Anthony, on the Charge of Illegal Voting, at the Presidential Election in Nov., 1872, and on the Trial of Beverly W. Jones, Edwin T. Marsh, and William B. Hall, the Inspectors of Election by Whom Her Vote was Received. It contained documents from the trial, including the indictments, her speech to potential jurors, the attorneys' arguments and motions, the trial transcripts, and the judge's ruling. It did not include the argument of U.S. Attorney Crowley because he refused to provide it. Instead, Crowley published his own pamphlet that contained his argument together with the judge's ruling. Anthony's book also contained an essay written after the trial by John Hooker, the reporter for Connecticut's Supreme Court of Errors, which said that Hunt's actions were "contrary to all rules of law" and "subversive of the system of jury trials in criminal cases".[66]

Helen Potter, a popular entertainer, performed reenactments of Anthony castigating the judge for years after the trial. A skilled impersonator of famous people, Potter performed across the country.[68] Anthony traveled to see Potter on stage in Illinois in 1877. After the performance (which did not include Anthony's speech), Potter signaled her support for Anthony's work by paying her hotel bill and donating $100 to her.[69]

The arrested women and some of their supporters formed the Women Taxpayers' Association of Monroe County in May 1873 to protest their situation of taxation without representation.[70]

The place where the arrested women voted now has a bronze sculpture of a locked ballot box flanked by two pillars, which is called the 1872 Monument, and was dedicated in August 2009, on the 89th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment. Leading away from the 1872 Monument there is the Susan B. Anthony Trail, which runs beside the 1872 Café, named for the year of Anthony's vote.[71]

On August 18, 2020, President Donald Trump symbolically pardoned Susan B. Anthony on the 100th Anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment.[72] The pardon was symbolic because there was no-one to accept it on Anthony's behalf; and it was publicly rejected by at least one of the late feminist's contemporary representatives, the National Susan B. Anthony Museum and House.[73]

Legal commentary

In the summer of 1874, the Albany Law Journal, the leading legal journal in New York state, criticized Judge Hunt's actions, saying, "Miss Anthony had no trial by jury. She had only a trial by Judge Hunt. This is not what the constitution guarantees."[74]

In 2001, the New York University Law Review published an article called "A Revolution Too Soon: Woman Suffragists and the 'Living Constitution'", which included a section on Anthony's trial. Its author, Adam Winkler, said the dominant mode of constitutional interpretation in the twentieth century, sometimes known as "Living Constitutionalism", is generally said to have originated around 1900 with such legal thinkers as Oliver Wendell Holmes, who believed that the constitution should be interpreted in ways that meet the present needs of society. Winkler points out, however, that the suffragists' New Departure strategy preceded those thinkers by urging the courts to declare that women's right to vote was a newly recognized natural right that was inherent in the constitution.[75]

"10 Trials that Changed the World", a group of articles published in 2013 in the ABA Journal (an organ of the American Bar Association), included an article called "Susan B. Anthony is Convicted for Casting a Ballot". Its author, Deborah Enix-Ross, chair of the ABA's Center for Human Rights, said the trial touched on many issues other than women's suffrage, "including the laws that supported Reconstruction, the competing authority of federal and state governments and courts, criminal proceedings in federal courts, the right to trial by jury and the lack of provisions to appeal criminal convictions."[76] She said that, "Justice Hunt's decision to direct the jury to find Anthony guilty—without allowing the jurors to deliberate and without polling them—was so egregious that lawyers, politicians and the press spoke out against his violation of the constitutional guarantee of trial by jury."[76] She also said, "Anthony's role in providing impetus for protecting a defendant's rights in jury trials should not be overlooked."[76]

See also

References

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 7

- 1 2 3 4 Gordon (2005), p. 46–47

- ↑ Wellman (2004), pp. 193, 195, 203

- ↑ DuBois (1978) p. 41

- ↑ DuBois (1998), pp. 119–120. It had not always been illegal for women to vote in New Jersey, whose 1776 constitution enfranchised all adult inhabitants, male or female, who owned a specified amount of property. New Jersey women were disenfranchised by a law passed in 1807. See Wellman (2004), p. 138

- ↑ DuBois (1998), pp. 98–99

- ↑ DuBois (1998), pp. 100, 122

- ↑ DuBois (1998), p. 100

- ↑ DuBois (1998), p. 120

- ↑ DuBois (1998), p. 119

- ↑ Gordon (2000), p. 526, footnote 4

- ↑ Cox, Rowland (ed.), "The American Law Times", The American Law Times Association (1871), Vol 4, pp. 199–200

- ↑ Barry (1988), p. 153

- ↑ Venet (1991), p. 148.

- ↑ Anthony was the nation's "best-known advocate of woman suffrage" per Gordon (2005), p. 1. Ann D. Gordon is the editor of the six-volume Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Similarly, Ellen Carol DuBois, an historian of the women's suffrage movement, said that at this time Anthony "was the most famous women suffragist in the nation", per DuBois (1998) p. 129

- ↑ Quoted in Barry (1988), p. 250

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 33

- 1 2 3 Barry (1988), pp. 249–51

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 1–2, 29–30. After she voted, Anthony wrote to her friend Elizabeth Cady Stanton, saying, "Well I have been & gone & done it!!—positively voted the Republican ticket—strait." That letter is archived at the Huntington Library, which provides a digital scan of Anthony's letter.

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 2, 61

- 1 2 Gordon (2000), pp. 531–533, footnote 1

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 28–29. Brief biographical information about each of the women can be found in Gordon (2000), pp. 528–529.

- ↑ Flexner, Eleanor (1959), Century of Struggle, p. 158. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674106536

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 30–31

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 11–12

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 4, 12, 37

- ↑ Major excerpts of this speech are in Gordon (2005), pp. 63–68. The complete speech is in Volume 2 of the History of Woman Suffrage, pp. 630–647

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 67

- ↑ Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1887), p. 638

- 1 2 3 Gordon (2005), p. 5

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 37

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 4

- 1 2 Gordon (2005), p. 34

- ↑ Susan B. Anthony (January 24, 1873). "Untitled letter". Retrieved January 7, 2018., published on the web by the University of Rochester Library.

- 1 2 Barry (1988), pp. 252–253

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 68

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 39

- ↑ Hull (2012), pp. 115–116, 158

- ↑ "The Trial of Miss Susan B. Anthony for Illegal Voting—The Testimony and the Arguments" (PDF). The New York Times. June 18, 1873.

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 9–10, 26

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 26

- ↑

- Hunt, Ward (Circuit Judge) (June 18, 1873). "United States v. Anthony (full judicial opinion)". Westlaw. Thomson Reuters Westlaw, publishing U.S. court opinion. (PDF archive at law.resource.org)

- ↑ "Susan B. Anthony / She is Found Guilty ... (and) She is Fined ..." The Chicago Daily Tribune. June 19–20, 1873. p. 1.

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 41–43

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 44–45. Commenting on the fact that the wording of Fourteenth Amendment could be used for such opposite purposes, historian Ellen Carol DuBois said that, "the universalities of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment, where federal citizenship is established, run headlong into the sex-based restrictions of the second section, where voting rights are limited." See DuBois (1998) p. 117.

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 5, 13

- ↑ Justice Ward Hunt (June 19, 1873). "Instruction to the Jury by the Court in the Case of United States vs Susan B. Anthony". Famous Trials web site By Professor Douglas O. Linder. Retrieved January 5, 2018. The text of Hunt's instructions to the jury can also be found in Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1887), beginning on page 675.

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 6–7, 15–17, 48–50

- ↑ Hull (2012), p. 150

- ↑ Harper (1898–1908), Vol. 1, pp. 444, 441

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 70

- ↑ Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1887), p. 689

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 7, 45–47

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 47

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 18

- 1 2 Gordon (2005), p. 7

- ↑ Quoted in Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1887), p. 714

- 1 2 3 Gordon (2005), p. 8

- ↑ Gordon (2005), pp. 13, 29

- ↑ Quoted in Gordon (2005), pp. 35–36

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 36

- ↑ Editorial (June 21, 1873). "Miss Anthony's Case". Trenton State Sentinel and Capital. Quoted in Gordon (2005), p. 69

- ↑ "The Woman Who Dared". New York Daily Graphic. June 5, 1873. p. 1. Quoted in Gordon (2005), p. 33

- ↑ Hewitt (2001), p. 212

- 1 2 3 Gordon (2005), pp. 18–20

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 34–36

- ↑ Potter's notations are explained in her book beginning on this page.

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 45

- ↑ Gordon (2003) pp. 296–297

- ↑ Gordon (2005), p. 29

- ↑ Contributed by AaronNetsky. "1872 Monument – Rochester, New York". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ↑ Haberman, Maggie; Rogers, Katie (August 18, 2020). "On Centennial of 19th Amendment, Trump Pardons Susan B. Anthony". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ↑ Crowley, James (August 21, 2020). "Why Did the Susan B. Anthony Museum Reject Trump's Pardon?". Newsweek. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ↑ Quoted in Gordon (2005), p. 36

- ↑ Winkler, Adam (November 2001). "A Revolution Too Soon: Woman Suffragists and the 'Living Constitution'" (PDF). New York University Law Review. New York University. 76 (November 2001): 1456. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Enix-Ross, Deborah. "Susan B. Anthony is Convicted for Casting a Ballot". ABA Journal. American Bar Association (November 2013). Retrieved January 23, 2018.

Bibliography

- Anthony, Susan B. (ed.) (1874), An account of the proceedings on the trial of Susan B. Anthony on the charge of illegal voting at the Presidential election in Nov., 1872, and on the trial of Beverly W. Jones, Edwin T. Marsh and William B. Hall, the inspectors of elections by whom her vote was received, Daily Democrat and Chronicle Book Print (1874), Rochester, New York. The creator of this 212-page book is not identified within the book itself, but Ann D. Gordon says that Anthony assembled the documents that comprise it and arranged for its publication. See Gordon (2005), p. 34.

- Barry, Kathleen (1988). Susan B. Anthony: A Biography of a Singular Feminist. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-36549-6.

- DuBois, Ellen Carol (1978). Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women's Movement in America, 1848–1869. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8641-6.

- DuBois, Ellen Carol (1998). Woman Suffrage and Women's Rights. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-1901-5.

- Gordon, Ann D., ed. (2000). The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: Against an aristocracy of sex, 1866 to 1873. Vol. 2 of 6. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2318-4.

- Gordon, Ann D., ed. (2003). The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: National protection for national citizens, 1873 to 1880. Vol. 3 of 6. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2319-2.

- Gordon, Ann D. (2005). "The Trial of Susan B. Anthony" (PDF). Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- Hewitt, Nancy A., 2001. Women's Activism and Social Change: Rochester, New York, 1822–1872. Lexington Books, Lanham, Maryland. ISBN 0-7391-0297-4.

- Hull, N. E. H. (2012). The Woman Who Dared to Vote: The Trial of Susan B. Anthony. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0700618491.

- Kern, Kathi, and Linda Levstik. "Teaching the New Departure: The United States vs. Susan B. Anthony". The Journal of the Civil War Era (2012), Vol. 2, No.1, pp: 127–141.

- Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; Anthony, Susan B.; Gage, Matilda Joslyn (1887), History of Woman Suffrage, Volume 2, Rochester, New York: Susan B. Anthony (Charles Mann printer). Pages 627–715 of this book provide extensive coverage of the trial from the point of view of Anthony and her allies.

- Venet, Wendy Hamand (1991). Neither Ballots nor Bullets: Women Abolitionists and the Civil War. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia. ISBN 978-0813913421.

- Wellman, Judith (2004). The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Women's Rights Convention, University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02904-6.

External links

- "Susan B. Anthony Criminal Case File" at the U.S. National Archives. Click on "item(s) described in the catalog" to see scans of the transcripts of the indictment, record of conviction, etc.

- * Hunt, Ward (Circuit Judge) (June 18, 1873). "United States v. Anthony (full judicial opinion)". Westlaw. Thomson Reuters Westlaw, publishing U.S. court opinion. (PDF archive at law.resource.org)

Articles published around the time of the trial

- "Susan B. Anthony in Court". The Boston Post. June 18, 1873. p. 2. — Includes defense arguments

- "The Decision of Judge Hunt". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 19, 1873. p. 4. — Newspaperman's case review and opinion piece advocating continued gender discrimination

- "Susan B. Anthony / She is Found Guilty ... (and) She is Fined ..." The Chicago Daily Tribune. June 19–20, 1873. p. 1. — Description of judicial opinion (June 19); and closing argument and sentencing (June 20)

- "Tea Party Teachings / Woman's Freedom Dawning / No Taxation Without Representation". The New York Herald. December 17, 1873. p. 10. — Includes Anthony's speech to the Union League Club, New York, on the centennial of the Boston Tea Party