| Trigoniidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Trigonia sp. (Cretaceous) near Austin, Texas. Scale bar is 10 mm. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Order: | Trigoniida |

| Superfamily: | Trigonioidea |

| Family: | Trigoniidae Lamarck |

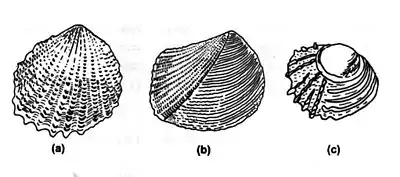

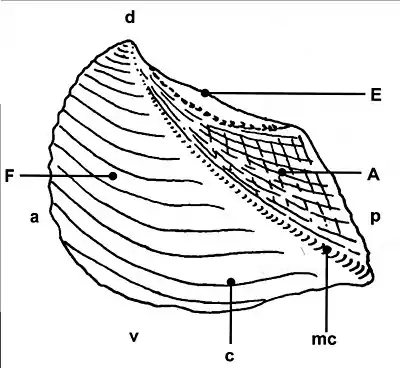

Trigoniidae is a taxonomic family of saltwater clams, marine bivalve mollusks in the superfamily Trigonioidea. There is only one living genus, Neotrigonia, but in the geological past this family was well represented, widespread and common. The shells of species in this family are morphologically unusual, with very elaborate hinge teeth, and the exterior of the shell is highly ornamented.

Description

The most striking feature of the Trigoniidae, which has attracted attention for centuries, is their external ornamentation. This is usually present as ribs or costae, or rows of aligned tubercles. The hinge teeth of the shell are unusually elaborate in structure. The living animal has no siphon.

Origin

This family originated from the Myophoriidae in the Triassic. The family underwent an explosion of diversity in the Jurassic, reaching a maximum of diversity in the Cretaceous, although most genera became extinct at the end of this period. Although they were abundant in the Mesozoic era, they are today represented by only one living genus, Neotrigonia, which inhabits waters off the coast of southern Australia.[1]

Discovery of a living genus

Before the beginning of the 19th century, no trigoniid had been described that was more recent than the Cretaceous Period. In 1802, however, François Péron discovered a living species in waters off the coast of Tasmania. Lamarck named it Trigonia margaritacea in 1804, with Cossmann renaming the genus Neotrigonia in 1912. Today, five living species have been identified, and are all found off the coast of Australia. Neotrigonia probably evolved from Eotrigonia (Eocene to Miocene) during the Miocene.[1]

The gills of Neotrigonia and fossil trigoniids are mineralized with calcium phosphate, which supports their chitinous scaffold support structures.[2]

Previous research

Because of their large size and pronounced ornament, fossil trigoniid bivalves have long attracted interest. Jean Guillaume Bruguiere was the first person to describe an example of Trigonia in 1789. Lamarck later figured specimens from the Oxfordian of France. In England the physician James Parkinson (the discoverer of Parkinson's disease) described examples of Trigonia and Myophorella. Later, James Sowerby and James De Carle Sowerby began to catalogue British examples in earnest. Etheldred Benett added several Upper Jurassic species, although her work was not primarily recognised due to the academic status of women at that time.[1]

In 1840 Europe, Louis Agassiz published a large volume entitled Memoire sur les Trigonies which recognised the large variation encountered within the family, dividing it into eight sections, which was a precursor to the generic classification that occurred some fifty years later. Other notable workers that described and figured trigoniids include Friedrich August von Quenstedt, Alcide d'Orbigny and Georg August Goldfuss.

The major worker on the Trigoniidae in the nineteenth century was John Lycett, a physician from Gloucestershire who published a text entitled A Monograph of British Fossil Trigoniae.[1]

Later research - the twentieth century

Work on the Trigoniidae has generally been sparse in the 20th century and has mainly concentrated upon the development towards a workable taxonomy. Today, knowledge is sufficient to divide the family into five Subfamilies (see below), which together contain more than sixteen genera, the most abundant being Trigonia, Myophorella, Laevitrigonia, and Orthotrigonia.[1]

Higher level taxonomy

- Family Trigoniidae

- Subfamily Trigoniinae

- Trigonia

- Neotrigonia - the only living genus

- Agonisca

- Maoritrigonia

- Praegonia

- Minetrigonia

- ?Pseudomyophorella

- Subfamily Prosogyrotrigoniinae

- Prosogyrotrigonia

- Prorotrigonia

- Subfamily Psilotrogoniinae

- Psilotrigonia

- Subfamily Myophorellinae

- Frenguilellella

- Jaworskiella

- Myophorella

- Vaugonia

- Orthotrigonia

- Scaphotrigonia

- Subfamily Laevitrigoniinae

- Laevitrigonia

- ?Liotrigonia

- Subfamily Trigoniinae

Family characteristics

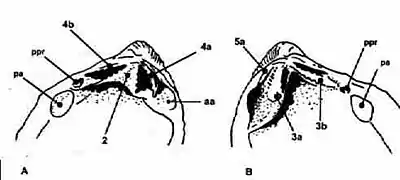

The trigoniid hinge

Members of the Trigoniidae are identified by the large and complex dentition that joins the two valves together and allows articulation. The teeth and supporting area can take up almost a third of the volume of the shell. The hinge structure is amongst the most complex of all bivalves, namely that the teeth are numerous and ridge-like with strong transverse striations. It is these striations which distinguishes the Trigoniidae from the more primitive Myophoriidae. The Trigoniidae almost certainly evolved by a monophyletic modification of a Triassic myophoriid, with three genera appearing in the Middle Triassic.[1]

Commonly found genera

Trigoniids are commonly found in both limestone, mudstone and sandstone in Jurassic and Cretaceous rocks all over the world. In Britain, examples are numerous in the Upper Jurassic rocks of the Dorset coast, particularly around the village of Osmington Mills. Other Jurassic rocks that yield specimens include the Cornbrash in Yorkshire and the Middle Jurassic sequence in the Cotswolds, particularly around Cleeve Hill, near Cheltenham.[1] Pterotrigonia (Scabrotrigonia) thoracica has been named state fossil of Tennessee.

Trigonia

The genus Trigonia is the most readily identifiable member of the family, having a series of strong ribs or costae along the anterior part of the shell exterior. They are the first representatives of the family to appear in the Middle Triassic (Anisian) of Chile and New Zealand. The first European examples (Trigonia costata Parkinson) turn up in the Lower Jurassic (Toarcian) of Sherborne, Dorset and Gundershofen, Switzerland.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Francis, A.O. 2000. The Palaeobiology of the European Jurassic Trigoniidae. Ph.D. thesis, University of Birmingham, 323pp.

- ↑ Whyte, M. A. (1991). "Phosphate gill supports in living and fossil bivalves". In S. Suga; H. Nakahava (eds.). Mechanisms and phylogeny of mineralization in biological systems. ISBN 4-431-70068-4.