| Umschlagplatz of the Warsaw Ghetto | |

|---|---|

National monument at the Ghetto's former Umschlagplatz symbolizing an open freight car, Stawki Street, Warsaw | |

Polish Jews loaded onto trains at the Warsaw Ghetto |

Umschlagplatz (German: collection point or reloading point) was the term used during The Holocaust to denote the holding areas adjacent to railway stations in occupied Poland where Jews from ghettos were assembled for deportation to Nazi death camps. The largest collection point was in Warsaw next to the Warsaw Ghetto. In 1942 between 254,000 – 265,000 Jews passed through the Warsaw Umschlagplatz on their way to the Treblinka extermination camp during Operation Reinhard,[1] the deadliest phase of the Holocaust in Poland.[2][3] Often those awaiting the arrival of Holocaust trains, were held at the Umschlagplatz overnight.[4] Other examples of Umschlagplatz include the one at Radogoszcz station - adjacent to the Łódź Ghetto - where people were sent to Chełmno extermination camp and Auschwitz.[5][6]

In 1988, a memorial was erected in Warsaw to commemorate the deportation victims from the Umschlagplatz. The monument resembles a freight car with its doors open. It is located on the corner of Stawki Street.[7]

Usage

Umschlagplatz is a German word that technically denotes a place where all goods for rail transport are handled.[8] The term was corrupted by the Nazis who used it as the euphemism for the location where people would be deported to the death camps. Like the use of Sonderbehandlung ("special treatment"),[9] Umschlagplatz dehumanized the activity.[10] It also disguised - through ambiguous language - what the purpose of the collection point was ultimately for, sending hundreds of thousands of people to their deaths. In January 1943 Heinrich Himmler received the Korherr Report, a statistical calculation on how many Jews remained in Europe; it made clear that people passed through the Umschlagplatz and that no other terminology would be employed.[11]

Warsaw Ghetto

During the Grossaktion Warsaw, which began on 22 July 1942, Jews were deported in crowded freight cars to Treblinka twice daily, in the early morning, often after an overnight wait, and in mid-afternoon. On some days as many as 10,000 Jews were deported. An estimated 300,000 Jews were taken to the Treblinka gas chambers; some sources describe it as the largest killing of a community in World War II. The mass deportation action ended on 21 September 1942, although trains to Treblinka continued to depart from 19 April 1943 until the end of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943.[12]

The Warsaw Umschlagplatz was created by fencing off a western part of the Warszawa Gdańska freight train station that was adjacent to the ghetto. The area was surrounded by a wooden fence, later replaced by a concrete wall. Railway buildings and installations on the site, as well as a former homeless shelter and a hospital were converted into a prisoner selection facility. The rest of the train station served its normal function for the rest of the city during the deportations.

The railway leading to the square was originally constructed in 1876, as a side rail to the city's main line. Warehouses and other buildings were built between 1921 and 1935.

After the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, and the occupation of the country, the square came under the administration of a dedicated German institution, the Transferstelle ("Transfer Bureau"). Originally its purpose was to oversee the flow of goods between the newly established Warsaw Ghetto and the "Aryan Side" of Warsaw. At the time the ghetto's inhabitants referred to the square as "Umschlag". At the end of January 1942, the southern portion of the square was incorporated into the ghetto.

Deportations to Treblinka

Starting in July 1942 the buildings located around the square began to be used by the Germans as places of selection. Jews were gathered and held there before deportation to the Treblinka death camp. The headquarters of the SS units responsible for the selections and deportations were located in the building of the old elementary school on Stawki Street. The Umschlagplatz was divided into two parts. The southern part, which was located within the walled ghetto, was the gathering point where those destined for transport awaited the arrival of the trains. The northern part included the rail and station where people were physically loaded onto the trains for Treblinka.

Initially, the roundups for the Umschlagplatz were supervised by the Jewish Ghetto Police. Houses or entire blocks were cordoned off and then all the inhabitants were forced to gather in a controlled spot, such as a closed off street or a tenement's courtyard. After a check of documents, the individuals were forced, under escort, to proceed to the Umschlagplatz. Emptied buildings were searched and those found hiding were either killed on the spot or joined with those proceeding to the square. Some young men were moved to the so-called Dulag, a temporary internment camp, from which some were sent to labor camps rather than death camps.

The order in which the ghetto's blocks were emptied was organized by the Germans. Beginning in August, German-run workhouses and factories (szopas) and the offices of the Judenrat were also cordoned off, and the personnel sent to the Umschlagplatz as well. Famed Polish pianist, Władysław Szpilman, would survive the ordeal by being pulled out of the crowds that were being loaded onto a train heading towards Treblinka. Szpilman was pulled from the line after being recognized by a Jewish policeman, who happened to stand guard at the Umschlagplatz. Szpilman's survival is described in his autobiography, The Pianist, which was made into a motion picture by Director Roman Polanski. Polanski, as well as his family, would also be affected by the Holocaust. Most of the people arriving in the Umschlagplatz were taken there via Zamenhof Street.

Memorial

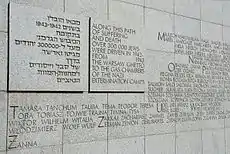

On 18 April 1988, on the eve of the 45th anniversary of the outbreak of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, a stone monument resembling an open freight car was unveiled to mark the Umschlagplatz. The inscription on four commemorative plaques in Polish, Yiddish, English and Hebrew reads:

Along this path of suffering and death over 300 000 Jews were driven in 1942-1943 from the Warsaw Ghetto to the gas chambers of the Nazi extermination camps.

The 400 most popular Jewish-Polish first names, in alphabetical order from Aba to Żanna, are engraved on the monument. Each one commemorates 1,000 victims of the Warsaw Ghetto. The gate is surmounted by a syenite grave stone (donated by the government and society of Sweden) with a motif of a shattered forest – a symbol of the extermination of the Jewish nation.

The selection and sequence of colours of the monument (white with the black stripe on the front wall) refer to the Jewish ritual clothing.[13] The monument was created by architect Hanna Szmalenberg and sculptor Władysław Klamerus. It replaced a commemorative plaque unveiled in the late 1940s. In 2002 the monument site and the adjacent school buildings were listed in the Register of Historic Monuments.[14]

Commemorative plaques and Jewish first names engraved on the monument

Commemorative plaques and Jewish first names engraved on the monument Umschlagplatz Monument, syenite grave stone

Umschlagplatz Monument, syenite grave stone The original ghetto tram in front of the Umschlagplatz Monument

The original ghetto tram in front of the Umschlagplatz Monument

See also

- Oyneg Shabbos chroniclers of the Warsaw Ghetto led by Emanuel Ringelblum

- Warsaw Ghetto boundary markers

References

- ↑ Holocaust Encyclopedia. "Warsaw Ghetto Uprising". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 2012-01-19 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Gitta Sereny (2013) [1974]. Into That Darkness. Pimlico / Random House. pp. 48, 330–331. ISBN 978-1-4464-4967-7.

- ↑ Robert Moses Shapiro (1999). Holocaust Chronicles. KTAV Publishing Inc. p. 35. ISBN 0-88125-630-7.

Gross Aktion of July to September.

- ↑ Michal Grynberg (2003). Words to Outlive Us: Eyewitness Accounts from the Warsaw Ghetto. Macmillan. p. 167. ISBN 1-4668-0434-3.

- ↑ Herman Taube (2007). Surviving Despair: A Story about Perseverance. AuthorHouse. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-4343-4846-3.

- ↑ Joseph Tenenbaum (2016). Underground, The Story of A People. Pickle Partners Publishing. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-78625-796-3.

- ↑ "Umschlagplatz memorial". www.google.com. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ↑ Johanna Rolshoven; Maria Maierhofer (2014). Das Figurativ der Vagabondage: Kulturanalysen mobiler Lebensweisen. Verlag. p. 35. ISBN 978-3-8394-2057-7.

- ↑ Lang, Berel (2003). Act and Idea in the Nazi Genocide. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2993-1.

- ↑ Shermer, Michael; Grobman, Alex (2009). Denying history: who says the Holocaust never happened and why do they say it?. University of California Press. pp. 89–92. ISBN 978-0-520-26098-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Special treatment" (Sonderbehandlung)". The Holocaust History Project. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ↑ Holocaust Encyclopedia (10 June 2013). "Warsaw Ghetto Uprising". US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ Wiesław Głębocki, Warszawskie pomniki, Wydawnictwo PTTK "Kraj", Warszawa 1990, p. 108

- ↑ Rejestr zabytów nieruchomych - Warszawa Archived 2012-09-13 at the Wayback Machine Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa, p. 47, Retrieved 11 August 2012

Bibliography

- Bernard Goldstein. Five Years in the Warsaw Ghetto. Dolphin, Doubleday. New York, 1961

- Emanuel Ringelblum. Kronika getta warszawskiego wrzesień 1939 - styczeń 1943. Warszawa 1988.