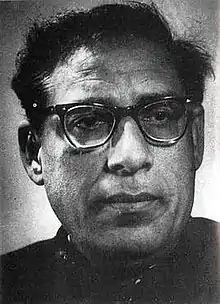

Amir Khan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | Sur Rang |

| Born | August 1912[1] Kalanaur, British India[2][1][3][lower-alpha 1] |

| Died | 13 February 1974 (aged 61)[4][5] Calcutta, West Bengal, India |

| Genres | Indian classical music (Khyal, Tarana) |

| Occupation(s) | Hindustani classical vocalist[5] |

| Years active | 1934 – 1974 |

| Labels | EMI, HMV, Music Today, Inreco, Ninaad, Navras, Columbia, The Twin |

| Awards: Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (1967) Presidential Award (1971) Padma Bhushan (1971) | |

Ustad Amir Khan (pronounced [əˈmiːr xaːn]; 15 August 1912[1] – 13 February 1974)[4][5] was one of the greatest and most influential Indian vocalists in the Hindustani classical tradition. He was the founder of the Indore gharana.[6][5]

Early life and background

Amir Khan was born in a family of musicians in Kalanaur, India.[2][1][3][lower-alpha 1] His father, Shahmir Khan, a sarangi and veena player of the Bhendibazaar gharana, served at the court of the Holkars of Indore. His grandfather, Change Khan, was a singer in the court of Bahadurshah Zafar. Amir Ali's mother died when he was nine years old. He had a younger brother, Bashir, who went on to become a sarangi player at the Indore station of All India Radio.

He was initially trained in the sarangi by his father. However, seeing his interest in vocal music, his father gradually devoted more time to vocal training, focusing on the merukhand technique. Amir Khan was exposed at an early age to many different styles, since just about every musician who visited Indore would come to their house, and there would be mehfils at their place on a regular basis.[1] He also learned the basics of tabla playing from one of his maternal uncles, who was a tabla player.

Amir Khan moved to Bombay in 1934, and there he gave a few concerts and cut about half a dozen 78-rpm records. These initial performances were not well received. Following his father's advice, in 1936 he joined the services of Maharaj Chakradhar Singh of Raigadh Sansthan in Madhya Pradesh. He performed at a music conference in Mirzapur on behalf of the Raja, with many illustrious musicians present, but he was hooted off the stage after only 15 minutes or so. The organizer suggested singing a thumri, but he refused, saying that his mind was never really inclined towards thumri. He stayed at Raigadh for only about a year. Amir Khan's father died in 1937. Later, Khansahib lived for some time in Delhi and Calcutta, but after the partition of India he moved back to Bombay.

Singing career

Amir Khan was a virtually self-taught musician. He developed his own gayaki (singing style), influenced by the styles of Abdul Waheed Khan (vilambit tempo), Rajab Ali Khan (taans) and Aman Ali Khan (merukhand).[5] This unique style, known as the Indore Gharana, blends the spiritual flavour and grandeur of dhrupad with the ornate vividness of khyal. The style he evolved was a unique fusion of intellect and emotion, of technique and temperament, of talent and imagination. Unlike other artists he never made any concessions to popular tastes, but always stuck to his pure, almost puritanical, highbrow style.[1]

Amir Khansahib had a rich baritone open-throated voice with a three-octave range. His voice had some limitations but he turned them fruitfully and effortlessly to his advantage. He presented an aesthetically detailed badhat (progression) in ati-vilambit laya (very slow tempo) using bol-alap with merukhandi patterns,[7] followed by gradually speeding up "floating" sargams with various ornamentations, taans and bol-taans with complex and unpredictable movements and jumps while preserving the raga structure, and finally a madhyalaya or drut laya (medium or fast tempo) chhota khyal or a ruba'idar tarana. He helped popularize the tarana, as well as khyalnuma compositions in the Dari variant of Persian. While he was famous for his use of merukhand, he did not do a purely merukhandi alap but rather inserted merukhandi passages throughout his performance.[8] He believed that practising gamak is essential to mastering singing.

Khansahib often used the taals Jhoomra and Ektaal, and generally preferred a simple theka (basic tabla strokes that define the taal) from the tabla accompanist. Even though he had been trained in the sarangi, he generally performed khyals and taranas with only a six-stringed tanpura and tabla for accompaniment. Sometimes he had a subdued harmonium accompaniment, but he almost never used the sarangi.[9]

While he could do traditional layakari (rhythmic play), including bol-baant, which he has demonstrated in a few recordings, he generally favored a swara-oriented and alap-dominated style, and his layakari was generally more subtle. His performances had an understated elegance, reverence, restrained passion and an utter lack of showmanship that both moved and awed listeners.[5] According to Kumarprasad Mukhopadhyay's book "The Lost World of Hindustani Music", Bade Ghulam Ali Khan's music was extroverted, exuberant and a crowd-puller, whereas Amir Khan's was an introverted, dignified darbar style. Amir Khansahib believed that poetry was important in khyal compositions, and with his pen name, Sur Rang ("colored in swara"), he has left several compositions.

He believed in competition between the genres of classical music and film and other popular music, and he felt that classical renderings needed to be made more beautiful while remaining faithful to the spirit and grammar of the raga ("बाज़ लोग ऐसे थे के जो खूब्सूरती बनाने के लिये वो राग को ज़रा इधर-उधर कर दिया करते थे, लेकिन मै यह कोशीश करता हूं के ज़्यादा से ज़्यादा राग खूब्सूरत हो लेकिन राग अप्नी जगह राग रहे"). He used to say, "नग़मा वही नग़मा है जो रूह सुने और रूह सुनाए" (نغمہ وہی نغمہ ہے جو روح سنے اور روح سناہے ; music is that which originates from the heart and touches the soul).

Characteristics of his style include:

- slow-tempo, leisurely raga development (except with Carnatic ragas, which he typically rendered in medium tempo)

- improvisation mostly in lower and middle octaves

- tendency towards serious and expansive ragas

- emphasis on melody

- clarity of notes

- judicious use of pause between improvisations

- bol alap and sargam using merukhand patterns

- using sargam in taan-ang

- using softer gamaks

- sparing application of murki

- use of kan swaras (acciaccatura) in all parts of performance

- controlled use of embellishments to preserve introspective quality

- rare use of tihai

- careful enunciation of text of bandish

- actual bandish as sung may or may not include antara

- multiple laya jatis in a single taan<note>Khansahib demonstrated this in an interview with the tabla player Chatturlal</note>

- mixture of taan types (including chhoot, sapaat, bal, sargam and bol-taan) in a single taan

- use of ruba'idar tarana (considered similar to chhota khyal)

Besides singing in concerts, Amir Khan also sang film songs in ragas, in a purely classical style, most notably for the films Baiju Bawra, Shabaab and Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje. This attempt to introduce classical music to the masses through films significantly boosted Khansahib's visibility and popularity. He also sang a ghazal Rahiye Ab Aisi Jagah for a documentary on Ghalib.

Khansahib's disciples include Amarnath,[6] A. Kanan, Ajit Singh Paintal, Akhtar Sadmani, Amarjeet Kaur, Bhimsen Sharma, Gajendra Bakshi, Hridaynath Mangeshkar, Kamal Bose, Kankana Banerjee, Mukund Goswami, Munir Khan, Pradyumna Kumud Mukherjee and Poorabi Mukherjee, Kamal Bandhopadhyay, Shankar Mazumdar, Shankarlal Mishra, Singh Brothers, Srikant Bakre and Thomas Ross. His style has also influenced many other singers and instrumentalists, including Bhimsen Joshi, Gokulotsavji Maharaj, Mahendra Toke, Prabha Atre, Rashid Khan, Ajoy Chakrabarty, Rasiklal Andharia, Sanhita Nandi, Shanti Sharma, Nikhil Banerjee, Pannalal Ghosh, the Imdadkhani gharana, and Sultan Khan. Although he referred to his style as the Indore Gharana, he was a firm believer of absorbing elements from various gharanas.[10]

Amir Khan was awarded the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1967[11] and the Padma Bhushan in 1971.[12]

Research in the field of Tarana

Ustad Amir Khan dedicated a large part of his musical career to the study of taranas. In his research, he found that the words used in Tarana come from Persian and Arabic languages. In one of his research articles he explained their meanings as follows:

Tanan Dar Aa - Enter my body.

O Dani - He knows

Tu Dani - You know.

Na Dir Dani - You are the Complete Wisdom.

Tom - I am yours, I belong to you.

Yala - Ya Allah

Yali - Ya Ali

In another interview, he also states the meaning of the following syllables:

Dar – Bheetar, Aandar (inside)

Dara – Andar Aa (get in or come inside)

Dartan – Tanke Aandar (inside the body)

Tanandara – Tanke Aandar Aa (Come inside the body)

Tom – Main Tum Hun (I am you)

Nadirdani – Tu Sabse Adhik Janata Hai (You know more than anyone else)

Tandardani – Tanke Aandarka Jannewala (One who knows what is inside the body)

Personal life

Amir Khan's first marriage was to Zeenat, sister of the sitar player, Vilayat Khan. From this marriage, which eventually failed and ended in separation, he had a daughter, Farida. His second marriage was to Munni Bai, who gave birth to a son, Akram Ahmed. Around 1965, Khansaheb married Raisa Begum, daughter of the thumri singer, Mushtari Begum of Agra. He had expected that Munni Begum would accept the third wife; however, Munni disappeared and it is rumored that she committed suicide. With Raisa he had a son, Haider Amir, later called Shahbaz Khan.[4]

Khansahib died in a car accident in Calcutta on 13 February 1974 aged 61, and was buried at Calcutta's Gobra cemetery.[4]

Discography

Movies

- Baiju Bawra (music director: Naushad)

- 'Tori Jai Jai Kartar' (raga Puriya Dhanashree; alternate version here)

- 'Sargam' (raga Darbari)

- 'Langar Kankariya Ji Na Maro' (raga Todi, with D. V. Paluskar)

- 'Aaj Gaawat Man Mero Jhoomke' (raga Desi, with D. V. Paluskar)

- 'Ghanana Ghanana Ghana Garjo Re' (raga Megh)

- Kshudhita Pashan (music director: Ali Akbar Khan)

- 'Kaise Kate Rajni' (raga Bageshree, with Protima Banerjee)

- 'Piya Ke Aavan Ki' (thumri in raga Khamaj)

- 'Dheemta Dheemta Derena' (tarana in raga Megh)

- Shabaab (music director: Naushad)

- 'Daya Kar He Giridhar Gopal' (raga Multani)

- Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje (music director: Vasant Desai)

- Title song 'Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje' (raga Adana)

- Goonj Uthi Shehnai (ragamala with Bismillah Khan)

- Bhatiyar

- Ramkali

- Desi

- Shuddh Sarang

- Multani

- Yaman

- Bageshree

- Chandrakauns

- Ragini

- 'Jogiya Mere Ghar Aaye' (raga Lalit)

78 rpm recordings

- Adana

- Hansadhwani

- Kafi

- Multani

- Patdeep

- Puriya Kalyan

- Shahana

- Suha Sughrai

- Todi tarana

Public and private recordings

- Abhogi - three versions

- Adana - longer performance of 'Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje' title song, one other version

- Ahir Bhairav - three versions

- Amirkhani (similar to Vachaspati)

- Bageshree - six versions

- Bageshree Kanada - five versions

- Bahar

- Bairagi - two versions

- Barwa

- Basant Bahar - two versions

- Bhatiyar - four versions

- Bhimpalasi - two versions

- Bihag - three versions

- Bilaskhani Todi - two versions

- Bhavkauns

- Chandni Kedar

- Chandrakauns

- Chandramadhu - two versions

- Charukeshi - two versions

- Darbari - ten versions

- Deshkar - four versions

- Gaud Malhar

- Gaud Sarang

- Gujari Todi - four versions

- Hansadhwani - three versions

- Harikauns

- Hem

- Hem Kalyan

- Hijaz Bhairav (a.k.a. Basant Mukhari) - five versions

- Hindol Basant

- Hindol Kalyan

- Jaijaiwanti

- Jansanmohini - five versions

- Jog - three versions

- Kafi Kanada

- Kalavati - six versions

- Kausi Kanada - four versions

- Kedar

- Komal Rishabh Asavari - four versions

- Lalit - seven versions

- Madhukauns

- Malkauns - three versions

- Maru Kalyan

- Marwa - three versions

- Megh - five versions

- Miya Malhar

- Multani - two versions

- Nand - three versions

- Nat Bhairav - two versions

- Pancham Malkauns

- Poorvi

- Puriya - three versions

- Puriya Kalyan

- Rageshree - two versions

- Ramdasi Malhar - two versions

- Ramkali - two versions

- Ram Kalyan (a.k.a. Priya Kalyan or Anarkali)

- Shahana - three versions

- Shahana Bahar

- Shree

- Shuddh Kalyan - two versions

- Shuddh Sarang (with drut section in Suha)

- Suha

- Suha Sughrai

- Todi - two versions

- Yaman

- Yaman Kalyan - three versions

Awards and recognitions

- Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1967[5][12]

- Presidential Award in 1971

- Padma Bhushan in 1971[12]

- Swar Vilas from Sur Singar Sansad in 1971

Notes

- 1 2 A tribute by the ITC Sangeet Research Academy instead reports Khan was born in Indore.[5]

External links

- Amir Khan recordings on www.sarangi.info Archived 19 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Biographical documentary on Amir Khan on YouTube, produced in 1970 by the Films Division of India

- Discography

- Dr. Ibrahim Ali's analysis of Amir Khan's gayaki

- Tribute from the ITC Sangeet Research Academy

- Forgotten Patterns - Preview of an article on Amir Khan by his disciple Thomas Ross

- LP cover images

- Pandit Nikhil Banerjee's article on Amir Khan

- Extracts from Pandit Amarnath's lec-dem on Amir Khan's gayaki

Bibliography

- Amarnath, Pandit (2008). Indore ke masihā: Paṇḍita Amaranathaji dwara Ustad Amir Khan sahab ke sansmaran (in Hindi). Pandit Amarnath Memorial Foundation. ISBN 978-81-7525-934-8.

- Kumāraprasāda Mukhopādhyāẏa (2006). The Lost World of Hindustani Music. Penguin Books India. pp. 95–. ISBN 978-0-14-306199-1.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Misra, Susheela (1981). "Ustad Amir Khan". Great masters of Hindustani music. Hem Publishers. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021 – via Indian Culture Portal.

- 1 2 Saxena, Sushil Kumar (1974). "Ustad Ameer Khan: The Man and his Art". Journal of the Sangeet Natak Akademi (31): 8. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021 – via Indian Culture Portal.

- 1 2 Wade, Bonnie C.; Kaur, Inderjit N. (2018). "Khan, Amir". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.48875. ISBN 9781561592630. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Banerjee, Meena (4 March 2010). "Immortal maestro (Ustad Amir Khan)". The Hindu newspaper. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Amir Khan - Tribute to a Maestro". ITC Sangeet Research Academy website. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- 1 2 Chawla, Bindu (26 April 2007). "Stirring Compassion of Cosmic Vibration". The Times Of India. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ↑ Thomas W. Ross (Spring–Summer 1993). "Forgotten Patterns: "Mirkhand" and Amir Khan". Asian Music. University of Texas Press. 24 (2): 89–109. doi:10.2307/834468. JSTOR 834468.

- ↑ Ibrahim Ali. "The Swara Aspect of Gayaki (Analysis of Ustad Amir Khan's Vocal Style)". Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ↑ Jitendra Pratap (25 November 2005). "Pleasing only in parts". The Hindu newspaper. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 21 September 2006. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ↑ "Beatstreet (The Legend Lives on...Ustad Amir Khan)". The Hindu newspaper. Chennai, India. 3 November 2008. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ↑ "Sangeet Natak Akademi Awards - Hindustani Music - Vocal". Sangeet Natak Akademi. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- 1 2 3 Padma Bhushan Award for Amir Khan on GoogleBooks website Archived 19 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine