The vascular cambium is the main growth tissue in the stems and roots of many plants, specifically in dicots such as buttercups and oak trees, gymnosperms such as pine trees, as well as in certain other vascular plants. It produces secondary xylem inwards, towards the pith, and secondary phloem outwards, towards the bark.

In herbaceous plants, it occurs in the vascular bundles which are often arranged like beads on a necklace forming an interrupted ring inside the stem. In woody plants, it forms a cylinder of unspecialized meristem cells, as a continuous ring from which the new tissues are grown. Unlike the xylem and phloem, it does not transport water, minerals or food through the plant. Other names for the vascular cambium are the main cambium, wood cambium, or bifacial cambium.

Occurrence

Vascular cambia are found in all seed plants except for five angiosperm lineages which have independently lost it; Nymphaeales, Ceratophyllum, Nelumbo, Podostemaceae, and monocots.[1] In dicot and gymnosperm trees, the vascular cambium is the obvious line separating the bark and wood; they also have a cork cambium. For successful grafting, the vascular cambia of the rootstock and scion must be aligned so they can grow together.

Structure and function

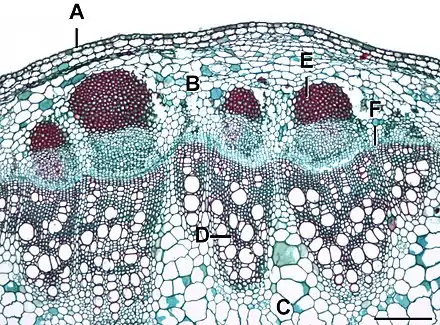

The cambium present between primary xylem and primary phloem is called the intrafascicular cambium (within vascular bundles). During secondary growth, cells of medullary rays, in a line (as seen in section; in three dimensions, it is a sheet) between neighbouring vascular bundles, become meristematic and form new interfascicular cambium (between vascular bundles). The fascicular and interfascicular cambia thus join up to form a ring (in three dimensions, a tube) which separates the primary xylem and primary phloem, the cambium ring. The vascular cambium produces secondary xylem on the inside of the ring, and secondary phloem on the outside, pushing the primary xylem and phloem apart.

The vascular cambium usually consists of two types of cells:

- Fusiform initials (tall, axially oriented)

- Ray initials (smaller and round to angular in shape)

Maintenance of cambial meristem

The vascular cambium is maintained by a network of interacting signal feedback loops. Currently, both hormones and short peptides have been identified as information carriers in these systems. While similar regulation occurs in other plant meristems, the cambial meristem receives signals from both the xylem and phloem sides for the meristem. Signals received from outside the meristem act to down regulate internal factors, which promotes cell proliferation and differentiation.[2]

Hormonal regulation

The phytohormones that are involved in the vascular cambial activity are auxins, ethylene, gibberellins, cytokinins, abscisic acid and probably more to be discovered. Each one of these plant hormones is vital for regulation of cambial activity. Combination of different concentrations of these hormones is very important in plant metabolism.

Auxin hormones are proven to stimulate mitosis, cell production and regulate interfascicular and fascicular cambium. Applying auxin to the surface of a tree stump allowed decapitated shoots to continue secondary growth. The absence of auxin hormones will have a detrimental effect on a plant. It has been shown that mutants without auxin will exhibit increased spacing between the interfascicular cambiums and reduced growth of the vascular bundles. The mutant plant will therefore experience a decrease in water, nutrients, and photosynthates being transported throughout the plant, eventually leading to death. Auxin also regulates the two types of cell in the vascular cambium, ray and fusiform initials. Regulation of these initials ensures the connection and communication between xylem and phloem is maintained for the translocation of nourishment and sugars are safely being stored as an energy resource. Ethylene levels are high in plants with an active cambial zone and are still currently being studied. Gibberellin stimulates the cambial cell division and also regulates differentiation of the xylem tissues, with no effect on the rate of phloem differentiation. Differentiation is an essential process that changes these tissues into a more specialized type, leading to an important role in maintaining the life form of a plant. In poplar trees, high concentrations of gibberellin is positively correlated to an increase of cambial cell division and an increase of auxin in the cambial stem cells. Gibberellin is also responsible for the expansion of xylem through a signal traveling from the shoot to the root. Cytokinin hormone is known to regulate the rate of the cell division instead of the direction of cell differentiation. A study demonstrated that the mutants are found to have a reduction in stem and root growth but the secondary vascular pattern of the vascular bundles were not affected with a treatment of cytokinin.

Cambium as food

The cambium of most trees are edible. In Scandinavia, it was historically used as a flour to make bark bread.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ Povilus, Rebecca A.; DaCosta, Jeffrey M.; Grassa, Christopher; Satyaki, Prasad R. V.; Moeglein, Morgan; Jaenisch, Johan; Xi, Zhenxiang; Mathews, Sarah; Gehring, Mary; Davis, Charles C.; Friedman, William E. (2020-04-14). "Water lily ( Nymphaea thermarum ) genome reveals variable genomic signatures of ancient vascular cambium losses". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (15): 8649–8656. Bibcode:2020PNAS..117.8649P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1922873117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7165481. PMID 32234787.

- ↑ Etchells, J. Peter; Mishra, Laxmi S.; Kumar, Manoj; Campbell, Liam; Turner, Simon R. (April 2015). "Wood Formation in Trees Is Increased by Manipulating PXY-Regulated Cell Division". Current Biology. 25 (8): 1050–1055. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.023. PMC 4406943. PMID 25866390.

- ↑ "So You Want to Eat a Tree". 20 May 2016.

External links

- Pictures of Vascular cambium

- Detailed description - James D. Mauseth

- Review; Risopatron, JPM; Sun, YQ; Jones, BJ (2010). "The vascular cambium: Molecular control of cellular structure". Protoplasma. 247 (3–4): 145–161. doi:10.1007/s00709-010-0211-z. PMID 20978810. S2CID 21775569.