In linguistics, a verb phrase (VP) is a syntactic unit composed of a verb and its arguments except the subject of an independent clause or coordinate clause. Thus, in the sentence A fat man quickly put the money into the box, the words quickly put the money into the box constitute a verb phrase; it consists of the verb put and its arguments, but not the subject a fat man. A verb phrase is similar to what is considered a predicate in traditional grammars.

Verb phrases generally are divided among two types: finite, of which the head of the phrase is a finite verb; and nonfinite, where the head is a nonfinite verb, such as an infinitive, participle or gerund. Phrase structure grammars acknowledge both types, but dependency grammars treat the subject as just another verbal dependent, and they do not recognize the finite verbal phrase constituent. Understanding verb phrase analysis depends on knowing which theory applies in context.

In phrase structure grammars

In phrase structure grammars such as generative grammar, the verb phrase is one headed by a verb. It may be composed of only a single verb, but typically it consists of combinations of main and auxiliary verbs, plus optional specifiers, complements (not including subject complements), and adjuncts. For example:

- Yankee batters hit the ball well enough to win their first World Series since 2000.

- Mary saw the man through the window.

- David gave Mary a book.

The first example contains the long verb phrase hit the ball well enough to win their first World Series since 2000; the second is a verb phrase composed of the main verb saw, the complement phrase the man (a noun phrase), and the adjunct phrase through the window (an adverbial phrase and prepositional phrase). The third example presents three elements, the main verb gave, the noun Mary, and the noun phrase a book, all of which comprise the verb phrase. Note, the verb phrase described here corresponds to the predicate of traditional grammar.

Current views vary on whether all languages have a verb phrase; some schools of generative grammar (such as principles and parameters) hold that all languages have a verb phrase, while others (such as lexical functional grammar) take the view that at least some languages lack a verb phrase constituent, including those languages with a very free word order (the so-called non-configurational languages, such as Japanese, Hungarian, or Australian aboriginal languages), and some languages with a default VSO order (several Celtic and Oceanic languages).

Phrase structure grammars view both finite and nonfinite verb phrases as constituent phrases and, consequently, do not draw any key distinction between them. Dependency grammars (described below) are much different in this regard.

In dependency grammars

While phrase structure grammars (constituency grammars) acknowledge both finite and non-finite VPs as constituents (complete subtrees), dependency grammars reject the former. That is, dependency grammars acknowledge only non-finite VPs as constituents; finite VPs do not qualify as constituents in dependency grammars. For example:

- John has finished the work. – Finite VP in bold

- John has finished the work. – Non-finite VP in bold

Since has finished the work contains the finite verb has, it is a finite VP, and since finished the work contains the non-finite verb finished but lacks a finite verb, it is a non-finite VP. Similar examples:

- They do not want to try that. – Finite VP in bold

- They do not want to try that. – One non-finite VP in bold

- They do not want to try that. – Another non-finite VP in bold

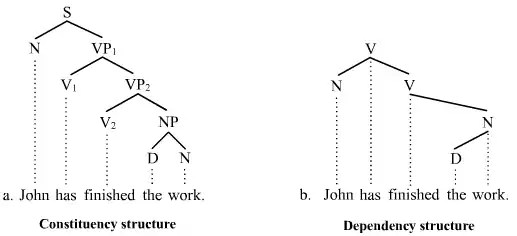

These examples illustrate well that many clauses can contain more than one non-finite VP, but they generally contain only one finite VP. Starting with Lucien Tesnière 1959,[1] dependency grammars challenge the validity of the initial binary division of the clause into subject (NP) and predicate (VP), which means they reject the notion that the second half of this binary division, i.e. the finite VP, is a constituent. They do, however, readily acknowledge the existence of non-finite VPs as constituents. The two competing views of verb phrases are visible in the following trees:

The constituency tree on the left shows the finite VP has finished the work as a constituent, since it corresponds to a complete subtree. The dependency tree on the right, in contrast, does not acknowledge a finite VP constituent, since there is no complete subtree there that corresponds to has finished the work. Note that the analyses agree concerning the non-finite VP finished the work; both see it as a constituent (complete subtree).

Dependency grammars point to the results of many standard constituency tests to back up their stance.[2] For instance, topicalization, pseudoclefting, and answer ellipsis suggest that non-finite VP does, but finite VP does not, exist as a constituent:

- *...and has finished the work, John. – Topicalization

- *What John has done is has finished the work. – Pseudoclefting

- What has John done? – *Has finished the work. – Answer ellipsis

The * indicates that the sentence is bad. These data must be compared to the results for non-finite VP:

- ...and finished the work, John (certainly) has. – Topicalization

- What John has done is finished the work. – Pseudoclefting

- What has John done? – Finished the work. – Answer ellipsis

The strings in bold are the ones in focus. Attempts to in some sense isolate the finite VP fail, but the same attempts with the non-finite VP succeed.[3]

Narrowly defined

Verb phrases are sometimes defined more narrowly in scope, in effect counting only those elements considered strictly verbal in verb phrases. That would limit the definition to only main and auxiliary verbs, plus infinitive or participle constructions.[4] For example, in the following sentences only the words in bold form the verb phrase:

- John has given Mary a book.

- The picnickers were being eaten alive by mosquitos.

- She kept screaming like a football maniac.

- Thou shalt not kill.

This more narrow definition is often applied in functionalist frameworks and traditional European reference grammars. It is incompatible with the phrase structure model, because the strings in bold are not constituents under that analysis. It is, however, compatible with dependency grammars and other grammars that view the verb catena (verb chain) as the fundamental unit of syntactic structure, as opposed to the constituent. Furthermore, the verbal elements in bold are syntactic units consistent with the understanding of predicates in the tradition of predicate calculus.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Concerning Tesnière's rejection of a finite VP constituent, see Tesnière (1959:103–105).

- ↑ For a discussion of the evidence for and against a finite VP constituent, see Matthews (2007:17ff.), Miller (2011:54ff.), and Osborne et al. (2011:323f.).

- ↑ Attempts to motivate the existence of a finite VP constituent tend to confuse the distinction between finite and non-finite VPs. They mistakenly take evidence for a non-finite VP constituent as support for the existence a finite VP constituent. See for instance Akmajian and Heny (1980:29f., 257ff.), Finch (2000:112), van Valin (2001:111ff.), Kroeger (2004:32ff.), Sobin (2011:30ff.).

- ↑ Klammer and Schulz (1996:157ff.), for instance, pursue this narrow understanding of verb phrases.

References

- Akmajian, A. and F. Heny. 1980. An introduction to the principle of transformational syntax. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Finch, G. 2000. Linguistic terms and concepts. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Klammer, T. and M. Schulz. 1996. Analyzing English grammar. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Kroeger, P. 2004. Analyzing syntax: A lexical-functional approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Matthews, P. 2007. Syntactic relations: A critical survey. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Miller, J. 2011. A critical introduction to syntax. London: continuum.

- Osborne, T., M. Putnam, and T. Groß 2011. Bare phrase structure, label-less structures, and specifier-less syntax: Is Minimalism becoming a dependency grammar? The Linguistic Review 28: 315–364.

- Sobin, N. 2011. Syntactic analysis: The basics. Malden, MA: Wiley–Blackwell.

- Tesnière, Lucien 1959. Éleménts de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck.

- van Valin, R. 2001. An introduction to syntax. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.