Violante Sánchez of Castile (before 1281 — after January 1330), was a Castilian noblewoman and by marriage Lady of Lemos, Sarria, Cabrera and Ribera.

In her own right, she was Lady of Ucero, Oímbra and Vilamartín de Valdeorras, among other towns,[1] and after becoming a widow, she professed as a nun in the Order of Santiago, to which she gave all her possessions in 1327, and was a patron and commander of the Monastery of Sancti Spiritus in Salamanca.

Life

Family origins

Violante Sánchez was the illegitimate daughter of the infante Sancho of Castile (who became King Sancho IV in 1295) and María de Meneses, Lady of Ucero. Her paternal grandparents were King Alfonso X of Castile and Violante of Aragon (after whom she was probably named)[2] and her maternal grandparents were the Ricohombre Alfonso Alfonso de Meneses "the Tizón" and Mayor González Girón.[3][4]

In addition, Violante Sánchez was the full-sister[lower-alpha 1] or illegitimate half-sister (although most modern historians assure the latter), of Teresa Sánchez of Castile, who married João Afonso Telo, 1st Count of Barcelos;[6][7] another illegitimate half-siblings were Alfonso Sánchez of Castile and Juan Sánchez. Among her legitimate half-siblings were King Ferdinand IV of Castile, infante Peter and infanta Beatrice, who became Queen consort of Portugal by her marriage to King Afonso IV.[8][9]

Youth and marriage to Fernando Rodríguez de Castro (1281–1305)

Violante's exact date of birth is unknown, although she must have been born before 1281.[7] During her childhood she was raised in the Castilian court, and María de Molina (who married her father in 1282) was her godmother.[10][11] Her mother, Maria de Meneses, who belonged to the high Castilian nobility and had been married to Juan Garcia de Ucero, Lord of Ucero,[12] entered a convent when the infante Sancho married with María de Molina, granddaughter of King Alfonso IX of León and his first cousin-once removed.[13]

Some authors, such as Antonio de Benavides y Fernández de Navarrete, erroneously called her María instead of Violante,[14] and others wrongly pointed out that in 1285 she married Fernando Rodríguez de Castro, although the historian Luis de Salazar y Castro demonstrated, based on different documents, that the marriage was carried out in 1293, as it can be deduced from a document granted in Layosa on 17 April of that year by Fernando Rodríguez de Casto, in which he revalidated the carta de arras that his father, Esteban Fernández de Castro,[15] had granted in 1291 in the name of his son for him being a minor a that time.

In the mentioned carta de arras, Esteban Fernández de Castro gave his daughter-in-law Violante the town and castle of Vilamartín de Valdeorras, located in the province of Ourense,[lower-alpha 2] and the cotos of Arcos de la Condesa, Sauceda, Valladares, Gullaes, Noguera, Caldelas and Pías, which were located in the lands of Santiago de Compostela and Toroño,[2] and to which were added the states of Ucero and Traspinedo, in the Esgueva Valley, which Violante inherited from her mother, and other possessions that it inherited from it in Burgos, Sahagún, Cea and Villafamor.[2] Her husband, Fernando Rodríguez de Castro, inherited the Lordship of Lemos and many other possessions and, like his father, held the position of pertiguero mayor (a title similar to the French Vidame) of Santiago de Compostela, which made him the most powerful Galician nobleman[17] during the reigns of Sancho IV and Ferdinand IV.[18]

In 1295 Violante's father King Sancho IV of Castile died and her half-brother Ferdinand IV ascended the throne, and in the Crónica of this sovereign was mentioned that Fernando Rodríguez de Castro died in 1304 during the siege of Monforte de Lemos, while fighting against infante Philip of Castile, Lord of Cabrera and Ribera, son of Sancho IV and another half-brother of Violante,[19] although other authors[20][21] as Antonio López Ferreiro, argued that in reality the siege of Lemos and the death of Fernando Rodríguez de Castro must have occurred in 1305, based on the testament that he granted on 17 December 1305 and that was consigned in the Tumbo B of the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral.[22]

Widowhood and relationship with her son (1305–1320)

After the death of Fernando Rodríguez de Castro, his assets were confiscated and most of them were handed over to Violante's half-brother infante Philip, who became, among other things, Lord of Lemos and Sarria, pertiguero mayor of Santiago de Compostela, Adelantado Mayor of Galicia and Comendero of the church of Lugo.[23] Violante then placed her eldest son, Pedro Fernández de Castro, who was about 15-years old, under the tutelage of the Galician nobleman Lorenzo Suárez de Valladares, who enjoyed, as various historians point out, "notable influences in the Portuguese Court". Lorenzo Suárez send his ward to the Kingdom of Portugal, in order to prevent Pedro Fernández from being persecuted by King Ferdinand IV of Castile, and entrusted him to Martín Gil de Riba de Vizela, Count of Barcelos, alférez of King Denis of Portugal, and mayordomo of his son and heir, the Infante Afonso, who educated and raised Pedro Fernández and in 1312 gave him the castle of Zagala.[21] The historian Eduardo Pardo de Guevara pointed out,[24] based on an affirmation of the chapter CLV of the Crónica de Alfonso XI,[25] that Pedro Fernández de Castro indeed grew up in the Portuguese Court with the infante Pedro, son and heir of King Afonso IV of Portugal, which would leave a "deep mark on his life".[26][lower-alpha 3]

On 9 June 1305 in the Ourense municipality of Oímbra, the Count of Barcelos, Martín Gil de Riba de Vizela, paid homage to Violante Sánchez for the castle of Oímbra and for the house of Guizón on the hands of Pedro Fernández de Castro, eldest son and heir of Violante, who had been entrusted by her to be raised by the Count of Barcelos.[30] And the latter also acknowledged in the document where the homage was recorded that he had those assets in her name, that they had been delivered to her by her father, King Sancho IV, and together with other minor provisions stated that the homage for these goods had been made in the presence of many noblemen.[31]

On 18 February 1316, in Ourense, Violante and her son Pedro reached a concord and shared all their assets, and agreed that he would have "for life" all the assets that her mother owned in the Kingdom of Galicia, including all her lands (heredamientos), houses, castles, churches or encomiendas, and that she would enjoy while she lived on all the assets that her son had in the Kingdom of León and would maintain ownership over the castle and the town of Vilamartín de Valdeorras.[32] In addition, Violante and her son mutually named themselves heirs in the event that one of them died, and agreed that they could not sell, alienate or pledge none of these assets,[33] and the French historian Charles García pointed out in 2006 that these clauses were probably suggested by Pedro Fernández de Castro, since that way he could dispose of his mother's assets in the future.[34]

On 15 December 1320, being in the Palencia municipality of Dueñas,[35] Violante donated to her son Pedro, as recorded on page 287 of Tumbo C of the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral, all the goods, including castles, fortified houses, churches, patronages or lordships that could belong to her in the Kingdoms of León and Galicia by either donations made to her by her father King Sancho IV, donations received from her late husband Fernando Rodríguez de Castro, or by whatever correspond to her of the inheritance of her mother María de Meneses and her uterine half-brother Juan García,[36] although there is no evidence that Violante had a brother named like that.[17] In this way, Pedro Fernández de Castro began to recover some of the assets that had belonged to his father, although it would be King Alfonso XI of Castile who would return most of them along with other charges, throughout of his reign.[37]

Violante Sánchez and the monastery of Sancti Spiritus in Salamanca (1325–1327)

In 1325 Violante Sanchez de Castilla began to exercise patronage, despite the discontent of the Grand Masters of the Order of Santiago[38] and the nuns of the Monastery of Sancti Spiritus in Salamanca, who claimed their right to choose their own commander.[39] At that time, the Monastery of Sancti Spiritus was one of the two most prominent hospital foundations that the Order of Santiago had in the Kingdom of León, followed by the town and castle of Castrotorafe, an uninhabited municipality located in the current province of Zamora.[38] Historian Charles García pointed out that the fact that Violante preference to profess as a nun in the Order of Santiago and not in a mendicant order could be due to her interest in obtaining political, economic and social power thanks to the possession of some of the assets of that Order, and also possibly due to the flexibility of the institution, since the nuns were not obliged to live cloistered.[40]

María Echániz Sans pointed out in 1991 that the patronage of the Monastery of Sancti Spiritus was exercised between 1268 and 1379 by four women, the first being María Méndez de Sousa, founder of the community and wife of Martín Alfonso de León, illegitimate son of King Alfonso IX.[41] The other three were Queen María de Molina, Violante Sánchez and Queen Juana Manuel of Villena, wife of Henry II of Castile and daughter of the famous magnate Don Juan Manuel.[41] Although the Kings of Castile didn't donate any possessions to the monastery, they confirmed its privileges on several occasions and protected it during their conflicts with the Order of Santiago or with the Salamanca city council.[42][lower-alpha 4]

Charles García also pointed out that it was Violante herself who asked Pope John XXII to entrust her with the administration of the Monastery of Sancti Spiritus in Salamanca and that of other encomiendas of the Order of Santiago,[43] and by means of two documents issued on 13 November 1325 in Avignon, the Pope entrusted the Archbishop of Toledo, John of Aragon, to grant the habit of the Order of Santiago to Violante, with the government of the Monastery of Sancti Spiritus and that of other encomiendas of the Order of Santiago,[44] which would ratify, in the opinion of said historian, a "factual situation".[43] During the brief period in which she was patron of the Monastery of Sancti Spiritus, Violante continued to request the Pope to entrust her with the administration of other properties of the Order of Santiago that would allow her to increase her income, since the rent extracted from Sancti Spiritus was of only 300 florins per year, and that surely, as Charles García pointed out, would be insufficient for her, so she asked the pontiff to grant her the direction of the encomienda of Puerto and the administration of the properties that the Order of Santiago owned in Toro and in the Dioceses of Astorga and Zamora, who could earn her an annual income of 750 florins.[43]

And in a document also issued on 13 November 1325 in Avignon, Pope John XXII entrusted the Archbishop of Toledo to follow the cause or lawsuit maintained by Violante and the Bishop of Osma, Juan Pérez de Ascarón, for the possession of the Lordship of Ucero, which legally belonged to her due to her mother's inheritance and had been illegally occupied and retained by said Bishop, according to her,[45] since he bought it on 23 May 1302 for 300,000 maravedís, and together with other properties, to the executors of Juan García de Villamayor, as stated in the deed of sale published in the volume II of the Memorias de Fernando IV de Castilla.[46] But despite the above, Violante continued to consider herself the owner of the Lordship and in 1327 she donated it, along with the rest of her possessions, to the Order of Santiago, despite the fact that Ucero belonged definitively from 1302 to the Bishops of Osma.[47]

A few days later, on 29 November 1325, Pope John XXII entrusted to the Archdeacon of Valderas, of the Bishopric of León, the cause of appeal that Violante, referred to in the document as the "patron" of the Monastery of Sancti Spiritus of Salamanca, had presented against Fernando Rodríguez, prior of the Convent of San Marcos of León, who had taken her to court for the thirteenth part of the income that the Salamanca monastery of Sancti Spiritus was supposed to deliver, as tithe, to said Leonese convent.[48][lower-alpha 5]

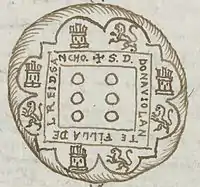

At this time, as noted by the heraldist Faustino Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, Violante used a personal seal in whose center appeared the coat of arms of her husband, six roundels of the House of Castro, surrounded by eight castles and lions placed on the outer lobes,[7] perhaps due to her condition of being the illegitimate daughter of King Sancho IV.[50] In the mentioned seal, which was drawn in the 17th century by the genealogist and historian Luis de Salazar y Castro in his work Pruebas de la Historia de la Casa de Lara, also appeared the legend «+ S. DOÑA VIOLANTE FIJA DEL REY DON SANCHO».[51]

On 30 May 1326, in the Ciudad Real municipality of Campo de Criptana, Violante renounced to the habit of the Order of Santiago and the administration of the Monastery of Sancti Spiritus in Salamanca and the other encomiendas of the Order that had been granted to her by the Pope John XXII, which included everything that the Order had in Toro and in the Bishoprics of Astorga and Zamora.[52] In act of renunciation she claimed to be unaware that all of this attempted, despite the pontiff's provisions, «contra la constituçion e estableçimiento e ordenamiento» of the Order of Santiago, that is, against its rules and constitutions.[53] Immediately after the renunciation, Violante Sánchez accepted again the habit of the Order of Santiago, this time from the Grand Master García Fernández himself, whom she promised to obey in the future as her master and lord.[54][55][lower-alpha 6]

One year later, on 27 December 1327,[51] Violante handed over to the Order of Santiago and to its his new Grand master Vasco Rodríguez de Coronado[lower-alpha 7] all the assets and rights she possessed, among which were included the Lordships and castles of Ucero and Vilamartín de Valdeorras, numerous cotos in Galicia, her lands in Burgos, which he inherited from her mother in Soria and Valladolid,[58] and all her other possessions in the Kingdoms of Castilla, León and Portugal, also providing that all those goods could be delivered, sold, pawned, exchanged or disposed of by the said Order,[59] since to be admitted to it, it was necessary for her to renounce all her personal assets.[34]

In the same day of the act of donation, Violante also granted the Grand Master of the Order of Santiago and his successors at the head of the Order a "letter of representation" (carta de personería) or general power of attorney so that they could represent her in any legal act, in ecclesiastical or secular trials, and also so that they could sue for her or on her behalf and defend her, along with other minor provisions on that general authorization, in which she had her seal stamped.[60]

Testament and death (1330)

On 24 January 1330 Violante made her will, in which she provided everything related to her executors to pay her debts and collect others, she bequeathed various amounts and other goods and belongings to numerous people, and requested the Grand Master of the Order of Santiago to allow that her remains be buried in the Monastery of San Francisco in Toro, to which he bequeathed various goods and objects and to whose friars he allocated a sum of 200 maravedis for a "pitanza" (distribution of food among poor people).[lower-alpha 8] Historian Charles García also highlighted the fact that she didn't order masses for her soul, which contrasted, for example, with the provisions of her stepmother, Queen María de Molina,[62] who had commissioned 10,000 masses sung for her soul in her will,[63] and stressed that Violante's will allows knowing her intimate thoughts, her social relationships, and the functioning of the world of the high Castilian nobility at the time of King Sancho IV and his grandson King Alfonso XI, who reigned in Castile at that time.[64]

At the beginning of her will, Violante declared that she was "en mio sano seso e en mía sana memoria" (in my healthy brain and in my healthy memory),[65] which was an indispensable requirement to be able to be a testator, and she entrusted her soul to Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, and Saint Mary Magdalene and the apostle James,[66] at the time which provided that upon her grave:[67]

Also, I ordered to my third parties to buy a coffin in which I ordered them to put me and in which they bury me and cover it with black tapestry with ribbons and with their folda and with the arms of Santiago placed on the tapestry over the coffin, I command that they made my buril with a stone that matches the ground and that of the stone that they put Santiago's arms on a epitaph that says like this: Here lies lady Violante, daughter of the most noble King Sancho and Maria Alfonso (lady who) was from Ucero. (« Aquí yas donna Violante fija del muy nobre rey don Sancho e de donna Maria Alfonso (señora que) fue de Osero»)

In her testament, Violante Sánchez again handed over all her assets to the Order of Santiago, asked the Grand Master of the Order to enforce her last wishes, annulled all the wills or codicils that she had granted until then,[67] and mentioned the inheritance that she had received from her parents, although not the assets she had received from her husband, Fernando Rodríguez de Castro, which led historian Charles García to point out that Violante's eldest son, Pedro Fernández de Castro, did not attempt to prevent the assets of his family went to the hands of the Order of Santiago.[34] And on 29 January 1330, five days after having granted the will, Violante added a clause to it in which she also designated her niece Queen María de Portugal, wife of Alfonso XI, as executor, begging her to respect and enforce her last wishes.[68] In addition, Charles García also pointed out that the fact that the priest of the church of San Julián de los Caballeros of Toro was mentioned in the will could indicate that Violante resided in the city of Toro at the end of her life.[69]

Violante's exact date of death is unknown, although she must have died after January 1330.

Burial

Violante's remains, in contravention to the provisions of her will, were buried in the Monastery of Sancti Spiritus of Salamanca, according to historians Ricardo del Arco y Garay,[70] Gil González de Ávila[71] and Bernardo Dorado, although the latter specified that she was buried in the church of the monastery,[72] where Martín Alfonso of León (illegitimate son of King Alfonso IX of León) and his wife María Méndez de Sousa, were also buried.[73][74]

Issue

From her marriage to Fernando Rodríguez de Castro, Lord of Lemos and Sarria, Violante had two children:

- Pedro Fernández de Castro (died 1342), Lord of Lemos, Monforte and Sarria. He held numerous positions, such as that of mayordomo mayor (lord steward) of King Alfonso XI of Castile, adelantado mayor de la frontera (governor) of Andalusia, and pertiguero mayor of Santiago de Compostela,[75] becoming in one of the most powerful Castilian noblemen during the reign of Alfonso XI, who awarded him numerous grants.[21]

- Juana Fernández de Castro (died 1316).[76] She married around 1314 with Alfonso of Valencia,[77] son of infante John of Castile, Lord of Valencia de Campos and Margaret of Montferrat.[78]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Luis de Salazar y Castro and Pedro de Salazar y Mendoza affirmed that Teresa Sánchez of Castile was the daughter of Sancho IV and María de Meneses, which would make Teresa a full-sister and not half-sister of Violante Sánchez.[5]

- ↑ In the carta de arras granted by Esteban Fernández de Castro to his daughter-in-law Violante Sánchez it's stated that the castle of Vilamartín de Valdeorras had been previously belonged to Rodrigo Fernández de Valduerna, Lord of Cabrera and Ribera and grandfather of Aldonza Rodríguez of León, wife of Esteban Fernández de Castro.[16]

- ↑ Later, Pedro Fernández de Castro had two illegitimate children with Aldonza Lorenzo de Valladares, daughter of his tutor:[27] a son, Álvaro Pires de Castro (later Count of Arraiolos and first Constable of Portugal)[28] and a daughter, Inês de Castro, who famously became in the lover and posthumously-recognized wife of King Pedro I of Portugal.[29]

- ↑ Different Kings of Castile assumed throughout history the encomienda of the Monastery of Sancti Spiritus. Queen María de Molina exercised it from approximately 1290 until her death in 1321, and King Alfonso XI assumed it in 1335.[42]

- ↑ On 14 December 1325, Pope John XXII wrote again to the Archdeacon of Valderas from Avignon to order him to take charge of the lawsuit between Violante Sánchez and the prior of the Convent of San Marcos of León convent.[49]

- ↑ The document by which Violante Sánchez renounced the habit of the Order of Santiago and took it back from the Grand master of said Order was also published by Luis de Salazar y Castro in his work Pruebas de la Historia de la Casa de Lara.[56]

- ↑ In the document of the donation, Violante Sánchez referred to herself as freila y comendadora of the Monastery of Sancti Spiritus in Salamanca, and declared that she was making this donation «estando en mi sano entendimiento e buena memoria, que do de grado e de buena voluntad, sin premia e fuerça ninguna....» (being in my healthy understanding and good memory, that I do of degree and of good will, without pressure and no force.....).[57]

- ↑ Charles García pointed out that Violante Sánchez's desire to be buried in the monastery of San Francisco of Toro could be related to the fact that her paternal grandmother and namesake, Queen Violante of Aragon, planned to be buried there at first, with the protection that the members of the royalty and the high nobility granted to the new mendicant orders, and also with the good reception that the female population gave to the sermons and preaching of the Franciscan friars. And although this historian pointed out the apparent contradiction of Violante Sánchez in wanting to direct a monastery of the Order of Santiago and, at the same time, be buried in one run by the Franciscans, who presented the most absolute poverty as a model of life, this may be related to the bad relations that she maintained with the nuns of said monastery and with the fact that at the beginning of the 14th century the Reconquista was practically paralyzed and the religious from the Order of Santiago were increasingly dedicated to rescuing the captives captured by the Muslims, this being one of their main charitable and humanitarian work.[61]

References

- ↑ Arco y Garay 1954, p. 273.

- 1 2 3 Pardo de Guevara y Valdés 2000a, p. 130.

- ↑ Sotto Mayor Pizarro 1987, pp. 226, 233.

- ↑ Pardo de Guevara y Valdés 2000a, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Salazar y Castro 1697, p. 437.

- ↑ Lourenço Menino 2012, p. 52.

- ↑ Lourenço Menino 2012, Genealogical scheme III.

- ↑ Lourenço Menino 2012, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Moreta Velayos et al. 1996, p. 173.

- ↑ García 2008, &2.

- ↑ Ibáñez de Segovia 1777, p. 406.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, p. 67.

- 1 2 Sotto Mayor Pizarro 1987, p. 233.

- ↑ Moxó 1969, p. 63.

- ↑ Pardo de Guevara y Valdés 2000a, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 Sotto Mayor Pizarro 1987, p. 234.

- ↑ López Ferreiro 1902, p. 269.

- ↑ Pardo de Guevara y Valdés 2000a, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Lourenço Menino 2012, p. 93.

- ↑ Cerdá y Rico 1787, p. 293.

- ↑ Pardo de Guevara y Valdés 2000a, p. 143.

- ↑ Sotto Mayor Pizarro 1987, pp. 30, 234.

- ↑ Sotto Mayor Pizarro 1987, pp. 30, 235.

- ↑ Sotto Mayor Pizarro 1987, p. 235.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, p. 74.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, p. 76.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, pp. 76–77.

- 1 2 3 García 2008, &6.

- ↑ Pardo de Guevara y Valdés 2000a, p. 144.

- ↑ López Ferreiro 1903, p. 144.

- ↑ Moxó 1969, pp. 63–64.

- 1 2 García 2008, &4 and 6.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1991, p. 61.

- ↑ García 2008, &20.

- 1 2 Echániz Sans 1991, p. 60.

- 1 2 Echániz Sans 1991, p. 64.

- 1 2 3 García 2008, &21.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, pp. 80–82.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, p. 82.

- ↑ García Guinea, Pérez González & Rodríguez Montañés 2002, p. 1125.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, p. 83.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, p. 84.

- ↑ García 2008, &4.

- 1 2 Salazar y Castro 1694, p. 669.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, p. 88.

- ↑ Ayala Martínez 2007, p. 244.

- ↑ Ayala Martínez 2007, p. 360.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Salazar y Castro 1694, pp. 668–669.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, p. 90.

- ↑ Peláez Fernández 2009, p. 194.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ García 2008, §8, 9 and 21.

- ↑ García 2008, &17.

- ↑ Larriba Baciero 1995, p. 206.

- ↑ García 2008, &7 and 12.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, p. 94.

- ↑ García 2008, &7.

- 1 2 Echániz Sans 1993, pp. 94–99.

- ↑ Echániz Sans 1993, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ García 2008, &60.

- ↑ Arco y Garay 1954, p. 181.

- ↑ González de Ávila 1650, p. 235.

- ↑ Dorado, Barco López & Girón 1863, p. 66.

- ↑ Rodríguez Gutiérrez de Ceballos 2005, p. 51.

- ↑ Arco y Garay 1954, p. 178.

- ↑ Salazar y Acha 2000, p. 387.

- ↑ Pardo de Guevara y Valdés 2000a, p. 131.

- ↑ Salazar y Acha 2000, p. 385.

- ↑ Salazar y Acha 2000, pp. 384–385.

Bibliography

- Arco y Garay, Ricardo del (1954). Sepulcros de la Casa Real de Castilla (in Spanish). Madrid: Instituto Jerónimo Zurita. CSIC. OCLC 11366237.

- Ayala Martínez, Carlos (2007). Las órdenes militares hispánicas en la Edad Media (siglos XII-XV) (in Spanish) (1ª ed.). Madrid: Marcial Pons, Ediciones de Historia S.A. y Latorre Literaria. ISBN 978-84-933199-3-9.

- Benavides, Antonio (1860a). Memorias de Don Fernando IV de Castilla (in Spanish). Vol. Tomo I (1ª ed.). Madrid: Imprenta de Don José Rodríguez. OCLC 3852430.

- Benavides, Antonio (1860b). Memorias de Don Fernando IV de Castilla (in Spanish). Vol. Tomo II (1ª ed.). Madrid: Imprenta de Don José Rodríguez. OCLC 253723961.

- Cerdá y Rico, Francisco (1787). Crónica de D. Alfonso el Onceno de este nombre (in Spanish) (2ª ed.). Madrid: Imprenta de D. Antonio de Sancha. OCLC 3130234.

- Dorado, Bernardo; Barco López, Manuel; Girón, Ramón (1863). Historia de la ciudad de Salamanca (in Spanish) (1ª ed.). Salamanca: Imprenta del Adelante – Ramón Girón (ed.). OCLC 644411876.

- Echániz Sans, María (1991). Universidad de Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca y Departamento de Historia Medieval, Moderna y Contemporánea (ed.). "El monasterio de Sancti Spíritus de Salamanca: Un espacio monástico de mujeres de la Orden Militar de Santiago (siglos XIII-XV)". Studia historica. Historia medieval (in Spanish). Salamanca (9): 43–66. ISSN 0213-2060. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- Echániz Sans, María (1993). Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca (ed.). El monasterio femenino de Sancti Spíritus de Salamanca: colección diplomática (1268-1400) (in Spanish). Volumen 19 de Textos medievales / Universidad de Salamanca (1ª ed.). Salamanca. ISBN 84-7481-748-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - García, Charles (2008). Université Paris-Sorbonne (Paris IV) (ed.). "Violante Sánchez, fille de roi et filleule de reine". E-Spania (in French). París: E-Spania: Revue électronique d'études hispaniques medievales (5). doi:10.4000/e-spania.11183. ISSN 1951-6169.

- García Guinea, Miguel Ángel; Pérez González, José María; Rodríguez Montañés, José Manuel — Centro de Estudios del Románico (Monasterio de Santa María la Real de Aguilar de Campóo (2002). Enciclopedia del románico en Castilla y León (in Spanish). Volumen 10 (1ª ed.). Aguilar de Campoo: Fundación Santa María la Real, Centro de Estudios del Románico. ISBN 84-89483-22-1.

- González de Ávila, Gil (1650). Diego Díaz de la Carrera (ed.). Teatro eclesiástico de las iglesias metropolitanas y catedrales de los Reynos de las dos Castillas, vidas de sus arzobispos y obispos y cosas memorables de sus sedes (in Spanish). Tomo III (1ª ed.). Madrid. OCLC 49990474.

- Ibáñez de Segovia, Gaspar (1777). Joachin Ibarra (ed.). Memorias históricas del Rei D. Alonso el Sabio i observaciones a su chronica (in Spanish). Madrid. OCLC 458042314.

- Larriba Baciero, Manuel (1995). Universidad de Alcalá: Departamento de Historia I y Filosofía (ed.). "El testamento de María de Molina". Signo: Revista de historia de la cultura escrita (in Spanish). Alcalá de Henares (2): 201–212. ISSN 1134-1165. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- López Ferreiro, Antonio (1902). Historia de la Santa A. M. Iglesia de Santiago de Compostela (in Spanish). Tomo V. Santiago de Compostela: Impresión y encuadernación del Seminario Conciliar Central. OCLC 682842812.

- López Ferreiro, Antonio (1903). Historia de la Santa A. M. Iglesia de Santiago de Compostela (in Spanish). Tomo VI. Santiago de Compostela: Impresión y encuadernación del Seminario Conciliar Central. OCLC 644528391.

- Lourenço Menino, Vanda Lisa (2012). A rainha D. Beatriz e a sua casa (1293-1359) (doctoralThesis) (in Portuguese). Tesis de doctorado dirigida por Bernardo Vasconcelos e Sousa (1ª ed.). Lisboa: Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. hdl:10362/8087.

- Moxó, Salvador de (1969). Instituto Jerónimo Zurita (ed.). Estudios sobre la sociedad castellana en la Baja Edad Media (in Spanish). Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, CSIC. pp. 1–211. OCLC 462164146.

- Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, Faustino (1982). Instituto Luis de Salazar y Castro (ed.). Heráldica medieval española: la Casa Real de León y Castilla (in Spanish). Volumen I. Hidalguía. ISBN 8400051505.

- Moreta Velayos, Salustiano; Iglesia Duarte, José Ignacio de la; García Turza, Javier; García de Cortázar y Ruiz de Aguirre, José Ángel (1996). Instituto de Estudios Riojanos (ed.). VI Semana de Estudios Medievales — Capitulo: Notas sobre el franciscanismo y dominicanismo de Sancho IV y María de Molina: Nájera, 31 de julio al 4 de agosto de 1995 (in Spanish) (1ª ed.). Nájera: Semana de Estudios Medievales (La Rioja). pp. 171–184. ISBN 84-89362-11-4.

- Pardo de Guevara y Valdés, Eduardo (2000a). Los señores de Galicia: tenentes y condes de Lemos en la Edad Media (Tomo I) (in Spanish). Edición preparada por el Instituto de Estudios Gallegos «Padre Sarmiento» (CSIC) (1ª ed.). Fundación Pedro Barrié de la Maza. ISBN 84-89748-72-1.

- Pardo de Guevara y Valdés, Eduardo (2000b). Los señores de Galicia: tenentes y condes de Lemos en la Edad Media (Tomo II) (in Spanish). Fundación Pedro Barrié de la Maza. ISBN 84-89748-73-X.

- Peláez Fernández, Palmira (2009). "Mujeres con poder en la Edad Media: las órdenes militares". Cuadernos de Estudios Manchegos (in Spanish) (Instituto de Estudios Manchegos ed.). Ciudad Real (34): 169–207. ISSN 0526-2623. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Rodríguez Gutiérrez de Ceballos, Alfonso (2005). Guía artística de Salamanca (in Spanish). León: Ediciones Lancia. ISBN 84-8177-103-1.

- Salazar y Acha, Jaime de (2000). La casa del Rey de Castilla y León en la Edad Media (in Spanish). Colección Historia de la Sociedad Política, dirigida por Bartolomé Clavero Salvador (1ª ed.). Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales. ISBN 978-84-259-1128-6.

- Salazar y Castro, Luis de (1694). Mateo de Llanos y Guzmán (ed.). Pruebas de la Historia de la Casa de Lara (in Spanish). Madrid. OCLC 493250082.

- Salazar y Castro, Luis de (1697). Mateo de Llanos y Guzmán (ed.). Historia genealógica de la Casa de Lara (in Spanish). Tomo III. Madrid. OCLC 493214848.

- Sotto Mayor Pizarro, José Augusto de (1987). Os Patronos do Mosteiro de Grijo (Evolução e Estrutura da Familia Nobre - Séculos XI a XIV) (in Portuguese). Tesis doctoral. Oporto. ISBN 978-0883-1886-37.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)