|

|---|

|

|

The visa history of Russia deals with the requirements, in different historical epochs, that a foreign national had to meet in order to obtain a visa or entry permit, to enter and stay in the country.

Kievan Rus'

Initially in Rus', allowing the entry of foreigners was fixed according to customary law. As a rule, the following categories of foreigners were granted admittance: merchants and travelers, mercenary soldiers, and, after the adoption of Christianity, priests, painters, and artisans engaged in the construction of churches.

In the tenth century, Rus' concluded treaties establishing procedural rules. The most notable of these was the Treaty with Byzantium in 911, concluded by Oleg of Novgorod, according to which a Russian who committed crimes in the Byzantine Empire, was sent for punishment to Rus, and a Greek was sent to Byzantium. Their property was subject to confiscation.[1]

Russkaya Pravda, the legal code of Rus', accorded foreigners equal rights with Russian citizens.

Grand Duchy of Moscow

Russkaya Pravda was also the main act regulating the status of foreign nationals in the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

Other highlights of the formation of the legal regime governing the entry, stay, residence, and movement of foreigners in the territory of Russia for the purpose of trade were treaties—between Novgorod and Sweden, the Treaty of Nöteborg (1323); and between Novgorod and Norway, the Treaty of Novgorod (1326)—allowing merchants of these countries to move freely along the Neva River.

During this period, foreigners entering Russia were issued a special document to travel across the country, the Proezjaya Gramota (Russian: Проезжая Грамота, English: Charter for journey).

Tsardom of Russia

In this period, legal regulation of the arrival and stay of foreigners in Russia continued to develop.

In the 16th-17th centuries the Russian borders were closed to the free entry of foreigners.

The Russian government was interested gaining the expertise of foreign specialists and to come to agreement with the monarchs of the country where such foreigners resided. In some cases, foreigners were accepted who arrived at the border on their own initiative, but acceptance of their services was preceded by a lengthy procedure to establish their identities and qualifications.

Foreigners were allowed to settle only in certain places, such as cities; and it was forbidden them to travel Russia unaccompanied by Russian officials. In the 16th-17th centuries, the influx of foreigners to Russia was small, and so did not require passport control, although almost every foreigner was in possession of a Posolsky Prikaz (Посольский Приказ, or "Ambassadorial Prikaz") issued by the foreign ministry.[2]

From the 16th century to the first half of the 17th, foreigners settled among the Russian population. Under pressure from the Church, in accordance with the Decree of 1652, areas, or quarters, were allocated on the outskirts of cities—such as Moscow's German Quarter—where immigrants from Western Europe settled and they were allowed to live according to their own customs. Staying in the city center was only permitted for those foreigners who converted to Russian religious belief.[3]

In the 17th century, the government sought to invite foreign manufacturers to Russia to establish sectors of important industries, and offered them favorable conditions for the activity, such as the donation of state-owned land for factories and plants, the right to the enterprises by inheritance, loans from the Treasury, and long term monopolies on the production of goods (15–20 years).

The Novotorgovyy Charter (Новоторговый Указ, or "New Trading Charter"), of 22 April 1667, was the first attempt at legislative regulation of the legal status of foreigners in the Russian state.[4] This act was narrowly focused, regulating only questions of entry by foreign merchants. In Moscow and other cities, only those who had a "special charter of trade, with a red seal" could enter. Those foreigners who did not have such a charter could trade only in Arkhangelsk and Pskov.

The reign of Peter the Great (1682-1725) is characterised by the formation of state administration on a large scale, the transformation of the Tsardom of Russia into the Russian Empire.

Russian Empire

Under the Russian Empire, legislation was enacted, in phases and in sufficient detail, to regulate the order of entry, and the period of residence, of foreigners in Russia. The legislation specified the categories of foreigners who had the right of free entry to the country, who could stay and gain citizenship, as well those who did not have such a right. Foreigners arriving in Russia had to have a passport of their country, and have a form giving permission for a specified period of stay. Rules of admission were not the same for all, and depended on the category or specialization and on other factors (nationality, the purpose of travel, religion, etc.).

The expulsion of foreigners from Russia was also regulated by legislation.

From 1649 to 1866 there were international instruments on the extradition of deserters, fugitives, and political prisoners, including instigators of 1866 and other violators.[5]

Large-scale changes began with Peter I's decrees of 13 December 1695 and 16 November 1696. According to the first decree—treating those foreigners who had "arrived for service"—"to pass all foreigners without detention", and to treat other visitors as "under former decrees". The second decree stated that "all foreigners, for whatever purpose they [came], having [been] asked, to pass without detention".[6]

The first half of the 18th century (1702-1762)

The regulation of the legal status of foreigners in the Russian Empire was connected with Peter I's reforms. Peter I, seeking to make Russia more powerful and in every possible way to improve and expand trade with foreign states, issued the Manifesto of 16 April 1702. "About a call of foreigners to Russia, with the promise [of freedom] of worship" opened Russia to free access by foreigners, who were guaranteed a number of rights, privileges, and freedom of worship.

The Manifesto of 1702 was a powerful spur to drawing up legislation regulating the entrance and departure of foreigners, resulting in open borders for foreigners. The ban lodges of the German Quarter were rescinded.

Entry into Russia was allowed only to persons of "military rank", merchants, and master craftsmen. Originally, provisions of the Manifesto of 1702 touched only military persons, craftsmen, and merchants. Later, other categories of foreigners whose expertise was wanted—including scientists and foreign jurists—were covered.

The decree of 31 August 1719 empowered the Office of Police Affairs to keep an accounting of foreigners coming to St. Petersburg from other countries, and then to send those accounts to various government departments—such as the Admiralty board, concerning those foreigners who came to serve in the fleet; the College of War, concerning service in the army; or the Collegium of Commerce, created in January 1722 in Moscow, which supervised questions of trade with foreign merchants. Thus were foreigners accredited to relevant agencies, which determined the terms of their residence and service.

A special passport ("pass")—a document for internal use, proving a person's identity—was issued to foreigners.

For their departure from Russia, foreigners received exit passports from the departments to which they were attached, the passports being stamped by the Collegium of Foreign Affairs with the mark of the chief of police showing the traveler was leaving no debts. Deadlines for departure were specified: from the capital, two days; from boundary provinces, three weeks; and from internal provinces, three months.

Thus, the freedom of movement across Russia for foreigners declared in the Manifesto of 1702 did not happen in practice. The continuing need for all foreigners to have "letters for journey", or "proezjaya gramota", and "passports", when traveling through the country or crossing its borders, was confirmed by further decrees—for example, the Decree of 30 October 1719. By the 1720s, a number of decrees of Peter I rigidly regulated the stay of foreigners in Russia, the issuance of such decrees being explained by internal and external factors.

From 1762 and until the end of the 18th century

This period can be characterized as the one where the most favored treatment was accorded foreigners in Russia. Extensive land allotments were given them; money and privileged tax status were provided. But such extensive privileges had negative side-effects, which consisted of isolation and the autonomy of foreigners from local laws. Foreigners lived and worked under their charters and lived as if they occupied a state within the state. During this period open access to the country was had even by Jews, who on pain of punishment had been forbidden to live in Russia.

On 4 December 1762, Catherine the Great, for practical reasons—increasing population, improving methods of agricultural cultivation and cattle-raising, and fostering improvements in housekeeping—published the Manifesto "[Concerning giving] permission to foreigners, except Jews, to arrive and settle in Russia and about free return for Russian people running abroad". This act resolved an issue of free entry of foreigners into Russia and granted them considerable rights and privileges, including the right of free settlement.

On 23 July 1763, there was the Imperial Manifesto of the empress "[Concerning giving] permission to all foreigners coming to Russia to settle in those provinces in which they will wish and [...] granted to them [by] right". This document in many respects defined immigration policy of Russia from 1760 to 1770.

The 1766 treaty of commerce between Great Britain and Russia provided, on the basis of reciprocity, "freedoms and benefits" for trade people.

During this period, a number of changes concerning entry into Russia and departure of foreign citizens were legislated, so that the admission of foreigners into Russian began to require only the presentation of a passport.[7]

The legal status of foreigners was fixed in regulations of the period—the Police Ustav of 1782 and Charter to the Cities of 1785. Article 121 of the Police Ustav assigned police the duty of accounting for foreigners in each city.

The stay of foreigners who were not in public service became legally regulated. The Charter to the Cities prescribed that foreign merchants and craftsmen who settled in the country but did not accept Russian citizenship, be recorded with the guild, as well as pay the established taxes and fees. They were recorded at the city office, and had no right to leave a certain place of residence (Art. Art. 12, 60). Article 129 of the Charter regulated the departure of foreigners from Russian cities. Foreigners were allowed to travel with their family out of the city only after notifying the municipal magistrates, confirming the payment of all debts and the local tax for three years.

The end of the 18th century - 1860

This period was associated with a number of legislative acts, of the Russian emperors Paul I and Alexander I, which introduced restrictions on the privileged legal status of foreigners in Russia. Beginning with the French Revolution and during the Napoleonic wars, the Russian government became very cautious regarding foreigners, mainly for political reasons. This led to various constraints, particularly affecting citizens of France and the French dependent states. In the period 1789-1820, entry for foreigners was difficult, with special surveillance for arriving foreigners. Paul I ordered that foreigners arriving in both the capital and other areas of Russia be strictly observed. On 26 December 1796, two decrees were issued concerning the surveillance of foreigners. In the first decree, the Moscow authorities were given the right to expel from the city untrustworthy foreigners. In the second decree, local authorities were obliged to ensure monitoring of all visiting foreigners, paying particular attention to the French and Swiss; suspicious foreigners could be expelled.[6]

In 1806, Alexander I issued a decree "On the expulsion from Russia of all French citizens and [those from] different German regions that will not want to receive citizenship; banning them entry into Russia without passports [from the] Minister of Foreign Affairs; the termination of the trade treaty with France".

The Manifesto of 1 January 1807 significantly restricted the rights of foreign merchants. However, nationals of those states with which Russia had concluded trade agreements, had prior rights over other foreigners.[8]

Restrictions of the rights of foreign trade and other fields existed until 1860.

1860-1917

In 1860, reforms in Russia and expansion of international cooperation led to legislation relaxing restrictions on the rights of foreigners that had existed before 1860. Alexander II signed the decree "On the rights of foreigners residing in Russia", which ordered that foreigners staying in Russia for trade, agriculture, and industry were guaranteed such rights as were enjoyed by citizens of Russia.

Under a decree of 1894, foreigners visiting Russia were to be given special passports, which were issued at Russian diplomatic missions and consulates, or to have their foreign passports confirmed there, by official seal.

In 1903, a charter regarding passports specified that foreigners arriving in Russia would receive their entry passport for a period of one year with the place of residence specified. Foreigners living in large cities were required to hand over their passports to a police office. From there passports, after being checked, were sent to special boards as before.

Before leaving the country, it was, again, necessary to wait until the police office had checked the holder's indebtedness; and after coordination with the board of foreign affairs, the exit visa was given. Passports of those who would travel by sea or were using courts in Russian ports were registered with the Admiralty board.

The regulations were numerous, detailed, and systematic. Since a significant number of foreigners lived in Russia in the late 19th century (in 1897 there were 605,500 foreign nationals - 0.5% of the population), the question of their legal status was of great political as well as economic significance.[9]

From the middle of 1914 till 1917 - there was a correction of the legal status of foreigners under the conditions of World War I, defined by a number of decrees issued during this period, especially noteworthy being the Decree "About Rules by Which Russia Will Be Guided during War of 1914" of 28 June 1914. These decrees limited the rights of all foreigners and practically deprived of all rights those foreign citizens of states hostile to Russia during war.

Soviet Union

Soviet Russia

After the October Revolution of 1917, the changed state ideology caused a corresponding change in the whole system as control of borders and their crossing points became paramount, which was gradually organized in such a way to prevent the penetration of external spies, counterrevolutionaries, politically harmful literature, or other agents of sabotage and terror.

On 2 December 1917, Leon Trotsky signed a decree for the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs "On showing passports upon entry to Russia". It attempted to restrict the entry into Russia persons without passports that were certified by the Soviet representative abroad.[10] In circumstances where a soviet representative acted in only one capital city in Europe, Stockholm, the value of the decision does not go beyond demonstrating intentions. In the same vein was an attempt to establish new rules for foreigners exiting from Russia. On 5 December 1917, a Resolution of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs imposed a ban on leaving the country, without permission from local councils, on citizens of the states which were at war with Russia. This was followed by two further 1917 decisions of the Council of People's Commissars, relaxing such travel bans on persons with special permission from the Commissariat for Internal Affairs and the Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, including diplomats, in accordance with international law, the decree determining the order of departure. At the same time, a decree allowed entry to Soviet Russia for political refugees who had received a personal certificate from established overseas emigrant committees, as well as diplomats of neutral or allied states, having a resolution from a Soviet embassy.

In July 1919, the first registration of foreign citizens in the territory of the RSFSR was announced, within 7 days after the publication of the resolution of the Commissariat for Internal Affairs. Foreigners had to fill out a questionnaire where, in addition to standard data, they were required to specify the time of arrival and the purpose of their visit to Russia, occupation at home and in Russia, party affiliation, marital status, and attitudes toward military service. It was also necessary to call guarantors (the Party or government workers, the factory committee, or Soviet institution) who could confirm the person's "loyalty to the Soviet regime." However, in 1919 it was not possible to bring order to the entry and residence of foreigners, with an ongoing civil war.

Formation of the USSR

The main work on the elimination of the previous shortcomings and to develop modes of entry and residence of foreigners in Russia belongs to the 1921-1925 period.

In 1921, all the old rules and regulations were abolished, and the Soviet Government began to issue new rules that met the normal requirements of international law. For example, entry was allowed only on special permits issued by the Russian plenipotentiary representative abroad, after filling out a questionnaire, in the form of a visa stamped in their passports, with the obligatory pictures attached thereto, if such were not already with the passport.

In 1923, the right to issue entry visas was granted Soviet consuls in countries where there were no plenipotentiaries (1925 - all consulates). Various types of visas allowed for entry, transit with the right of entry and exit, and temporary residence allowing multiple border crossings. The visa was issued by applying mastic stamp on the document that served as a residence passport, with the traveler put on a visa list that followed to the destination. An entry visa of any kind was valid for 14 days, with a visa granting the right of re-entry good for 1 month.[11]

After World War II

After the World War II, the Soviet Union began arriving foreigners to train highly qualified specialists to create cadres of the communist asset of the new Europe that can ensure the implementation of the program of socialist construction. Since 1946 in the Soviet Union began to study students from Albania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, from 1947 - North Korea, since 1949 - China, since 1951 - from East Germany and Vietnam, since 1960 - Cuba.

For some military armies, primarily taking place in the USSR training was introduced a simplified procedure of exit and entry into the country. From 1945 – 1946 years of visa obtained in a simplified manner by officers of Army of Poland, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Mongolia. Only after the Yugoslav crisis in 1948 a simplified visa procedure for them has been canceled.[12]

All work with the foreigners was based on obsolete regulatory legal acts, departmental instructions 1925-1935. Non-compliance of certain provisions of these documents to new conditions created numerous difficulties. Students were required to obtain a visa to enter and leave every time, execution and coordination of different departments of visas takes time. To optimize this line of work in 1950 adopted a special instruction in 1953 pleased the decision on visa facilitation for foreign students.[13]

The liberalization of the visa regime

19 July 1959 the Council of Ministers approved the "Regulation on the entry into the USSR and exit from the USSR".[14] The entry of foreign citizens in the USSR permitted for foreign passports and other documents replacing them, in the presence of Soviet entry visas.[15] For the first time entry into the USSR became possible not only according to the international passport.

Treaty regulatory documents, terms and conditions for obtaining visas or the abolition of visas for certain categories of citizens of the socialist countries in Europe have been concluded the Government of the USSR with Bulgaria (1965, 1969), Czechoslovakia (before 1969, 1969), Hungary (1969), Poland (before 1970, 1970), Romania (1956, 1963, 1966 1969), Yugoslavia (1965, 1967).

24 June 1981 the Supreme Soviet of the USSR adopted a law "On the Legal Status of Foreign Citizens in the USSR» №5152-x. Foreign nationals arriving in the USSR are obliged to register their foreign passports or equivalent documents in place to stop and get out of the Soviet Union after a certain period of stay.[16]

Since 70s years with socialist countries were signed standard visa-free agreement, which replaced all previously existing arrangements. For entry to the USSR for tourist trips was needed a voucher, for private trips - invitation, transit without a visa. With Bulgaria in 1978, Cuba in 1985, Czechoslovakia in 1981, Hungary in 1978, North Korea in 1986, Poland in 1979, Romania in 1991, Yugoslavia in 1989.

Russian Federation

General Rules

The law "On the legal status of foreign citizens in the USSR" was adopted by the Russian Federation. The law took effect 1 January 1993.

Chapter III of the law, "entry into the USSR and exit from the USSR Foreign citizens", was replaced by Federal Law No.114-FZ 1996, "On the Order of Exit from the Russian Federation", which itself was repealed with the adoption of Federal Law 115-FZ on 25 Jul 2002, "On the Legal Status of Foreign Citizens in the Russian Federation".

The laws establish that, as a general rule, all foreign citizens and stateless persons need visas for entry and exit from the territory of Russia and the period of temporary stay is 90 days within a 180-day period. It also establishes a number of exceptions for certain groups of travelers.

The basis of the legal status of foreign citizens and stateless persons are secured primarily by the Constitution of the Russian Federation 1993, articles 62 and 63.[17]

According to the Russian Constitution, international treaties of Russia override domestic legislation. Russia has concluded a number of bilateral or multilateral treaties on visa abolishment or simplification and is seeking to negotiate new such treaties. The visa policy of Russia is based on the principle of reciprocity.

- Crimea

In April 2014, Crimea's tourism minister proposed a visa-free regime for foreign tourists staying at Crimean resorts, for up to 12 days, and a 72-hour visa-free stay for cruise passengers. Visa-free access for Chinese citizens was proposed in June 2014.[18] Visa-free entrance to Sevastopol began from September 2015.[19] Other parts of the proposals have been not realized.

- Visa-free travel

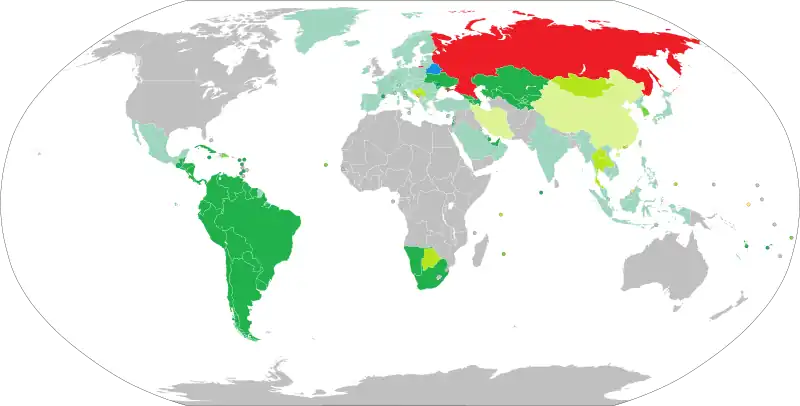

The citizens of 45 countries and territories are eligible to visit Russia with a valid passport, without obtaining a visa in advance.[20] These rules generally apply to holders of ordinary passports; rules for holders of diplomatic passports and other travel documents may differ.

From 2014, citizens of the countries—except Belarus, who have the right to a visa-free entry to Russia—must not stay longer than 90 days within any 180 day period. Resetting the allotted period by leaving and re-entering the country is no longer allowed.

- Visa-free 72-hour transit

In September 2013, the president of Russia sent to parliament a bill introducing 72-hour visa-free transit. A list of airports and a list of countries whose citizens would be able to use visa-free transit for tourist purposes, was to be approved by the Government of the Russian Federation after ratification. In 2014, the parliament had suspended ratification of the bill for an indefinite term.[21]

- 72-hour stay for Kaliningrad visit

From 1 February 2002, citizens of Schengen states, the United Kingdom, and Japan might visit the Kaliningrad region as tourists and obtain a 72-hour visa at the border check points of Bagrationovsk, Mamonovo, and Khrabrovo Airport, if travel is arranged through an approved travel agency.

The Russian Government was planning to cancel this service in 2015, but after appeals by officials of the Kaliningrad region, and the MFA of Russia, the service was extended through 2015.[22] Addressing parliament, the Minister of Foreign Affairs reported on extension of the service until 2016.[23] The service was cancelled from 1 January 2017.[24]

- E-visa to visit certain regions of the Far East

In 2015, Vladivostok again received, 106 years after it was cancelled, the status of "porto franco" (free port) by Federal Law №212-FZ, "On the free port of Vladivostok",[25] signed by the President of the Russian Federation on 13 July 2015 and taking effect 12 October 2015.

A simplified visa scheme was supposed to be made effective on July 1, 2016, but was postponed due to the lack of regulations passed by the State Duma.[26]

On 29 December 2016 the law was submitted for consideration to Parliament.[27]

Among other simplifications of government procedures, a visa-free regime was to be implemented, but a draft decree wasn't agreed to by government departments.

Starting August 2017, citizens of 18 countries can get an e-visa to visit regions in the Russian Far East. Eligible countries:

Eligible ports of entry

| Port of entry | Areas permitted to stay | Effective date |

|---|---|---|

| Vladivostok International Airport | Primorsky Krai | August 2017 |

| Sea passenger terminal of Vladivostok | ||

| Sea port of Posyet | 2018 | |

| Sea port of Zarubino | ||

| Sea port of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky | Kamchatka Krai | |

| Sea port of Korsakov | Sakhalin Oblast |

- International events

Art events

Participants and members of delegations coming to participate in musical events are either provided with a simplified visa regime (e.g. Eurovision Song Contest 2009) or the right of visa-free entry (e.g. International Tchaikovsky Competition 2015).[28]

As of September 2015 a law permanently abolishing visa requirements for participants and jury members of art competitions is being planned by the Government of Russia. The focus of this regulation will be the International Tchaikovsky Competition.[29]

Economic events

Participants in the 1st Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok did not require visas. Entrance was allowed with passport and an accreditation certificate only.[30]

Sporting events

Prior to the adoption of a special law, participants and members of delegations arriving for sporting events, couldn't count on visa-free entry or visa facilitation unless determined by law for each event. On 13 May 2013, a presidential decree on the abolition of visas for athletes, coaches, team leaders, members of foreign official delegations, and judges of international sports competitions came into effect. The law allowed entry on the basis of passport and accreditation certificate.[31] An order of the President of Russia is sufficient for abolishing or simplifying visa requirements.

Visas were abolished for participants of the 2013 Summer Universiade,[32] the 2014 ICF Canoe Sprint World Championships in Moscow, the 2014 World Judo Championships in Chelyabinsk, and the 16th FINA World Championships in Kazan.[33] Participants of the XVI World Aquatics Championships in the Masters category were exempted from visa fees.[34]

The right to enter Russia without a visa was also given to visitors during the 2014 Winter Olympics and 2014 Winter Paralympics in Sochi, if they were in a possession of tickets for the event.[35]

Teams participating in the 2016 IIHF World Championship were able to obtain visas on arrival. For the fans there was a simplified procedure for being issued visas.[36]

2018 FIFA World Cup

2018 FIFA World Cup holders of tickets for matches of the championship will be able to enter Russia without a visa with personalized card of viewer (also known as the passport of a fan or fan-ID) and national passport from 4 June to 15 July 2018.

- Transit through the Republic of Belarus

FAN ID holders entering the Russian Federation territory in the period from 4 June to 15 July and exiting the Russian Federation territory from 4 June to 25 July 2018 have the right of visa-free transit through the territory of the Republic of Belarus with FAN ID both on a laminated form and in electronic form and a valid identity document (passport) in the period from 4 June to 25 July 2018.[37][38] Holders of a fan passports or FAN IDs can cross the Russia-Belarus border if they travel via the motor road and railway routes through checkpoints that are not international.

Similarly eased restrictions are planned for visitors to the 2017 FIFA Confederations Cup and to the 2018 FIFA World Cup.[39] From 4 June to 25 July 2018, visas won't be required for those attending matches of the 2018 FIFA World Cup championship, who will be able to enter Russia with an ID and passport. Foreigners participating in events and FIFA athletes, will have to obtain visas, but with a simplified procedure. In particular, such visas will be issued within 3 working days from the date of filing and without payment of consular fees. This procedure will last until 31 December 2018.

Foreigners involved in activities and not participating in sporting events, will travel to and from Russia on ordinary multiple-entry work visas that will be issued for a period of 1 year. Foreigners entering to work for FIFA events, its subsidiaries and contractors, confederations, national football associations, the Russian football Union, or the "Russia-2018" organizing committee will be entitled to work in Russia without obtaining a work permit.[40]

ex-USSR

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union gave way to 15 separate states, visa, consular, customs, and border issues were concluded by unilateral and multilateral agreements within a few years.

- Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania

From 1 July 1992, Estonia has required visas for visiting Russian citizens; the visa issued in Moscow cost 10 dollars, at the border it cost 30 dollars.[41] The government of Pskov Oblast, in response, required that similar fees be collected from citizens of Estonia coming to Russia; but that was repealed as violating Russian law. On 1 June 1993, Estonia stopped issuing visas at the border; the visa could be issued only in Moscow or St. Petersburg.[42][43]

At the end of 1996, Russia and Estonia agreed on simplified border crossings by residents of border areas, affecting 10,000 residents of Ivangorod and Narva. On 11 September 2000, Estonia unilaterally abolished the simplified border regime.[44]

Since 22 March 1993, Latvia has required visas for citizens of Russia.[45] On 13 April 1993, in response, Russian Prime Minister Victor Chernomyrdin signed the government resolution "[On the] introduction of a visa allowing [entry] of citizens of the Republic of Latvia and the Republic of Estonia on the territory of the Russian Federation".[46] the resolution taking effect after 30 days.[47] For citizens of the former USSR permanently residing in Estonia and Latvia and not having citizenship, visa-free entry into Russia was allowed until 6 February 1995.

In December 1994, Russia and Latvia signed an agreement allowing simplified border crossing for residents of border areas on special lists. On 10 October 2000, Latvia unilaterally denounced the agreement.[48]

Holders of an alien passport of Estonia and holders of a non-citizen passport of Latvia who were citizens of the Soviet Union (meaning born on or before 6 February 1992) are visa-exempt for 90 days within any 180 day period.

On 17 June 2008, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed a decree "On the order of entry into the Russian Federation and exit from the Russian Federation, stateless persons, citizens of the USSR living in the Republic of Latvia and the Republic of Estonia",[49] which allowed holders of Estonian or Latvian passports to stay in Russia for up to 90 days within any 180-day period.

As of November 2016, a draft law that will allow visa-free entry to non-citizens of Estonia and Latvia born after 6 February 1992 is in the process of being adopted.[50]

from 1 October 1993, Lithuania banned the entry of those with internal documents, and, from 1 November 1993, introduced a visa regime.[51][52] On 24 February 1995, Russia and Lithuania signed an agreement, to take effect 25 June, allowing citizens of both countries to obtain visas in advance. Special protocols established a visa-free regime between Lithuania and the Kaliningrad region. On 1 January 2003, the agreement was terminated by Lithuania.[53]

After joining the EU in 2004, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania introduced a full visa regime with Russia in harmony with those of the Schengen Agreement, where visa issues are decided by the European Commission.

- Commonwealth of Independent States

On 9 October 1992, Russia signed a multilateral agreement on visa-free movement of citizens of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).[54] Under the agreement, citizens of Armenia, Belarus, Georgia (from 1 July 1995), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan might be on each other's territory without visas, for unlimited periods bearing all types of identity cards.

On 16 June 1999, Turkmenistan withdrew from the agreement. Turkmenistan and Russia signed an agreement regarding mutual trips of citizens on 17 July 1999. Under the agreement, holders of ordinary passports had to obtain a visa in advance, holders of diplomatic and service passports are exempted for stays of 30 days.[55]

After the election of President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin there was a revised visa agreement. On 3 December 2000, Russia withdrew from the CIS multilateral visa agreement.

Since then, the citizens of Georgia must obtain a visa in advance, under an agreement renegotiated due to a terrorist threat.[56]

Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Russia recognized the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2008. There have been agreements on visa-free trips for those on all types of passports. Citizens of Abkhazia and South Ossetia can be in Russia without visas for 90 days. In March 2015 Russia and South Ossetia signed a Treaty on Alliance and Integration, which in article 6, paragraph 4, "abolished restrictions on the length of stay of citizens[...] on mutual visa-free trips of citizens[...]". The Treaty entered into force on 30 July 2015.[57]

Azerbaijan and Ukraine refused to sign the multilateral agreement on travel. In 1997, under individual agreements, citizens of these countries have the right to enter the territory of Russia's without visas for unlimited periods of time.

Azerbaijan. Until 1997, the entry regime between Azerbaijan and Russia wasn't established legally. Azerbaijani citizens could stay in Russia, without visas, with all types of documents indefinitely, subject to the rules of internal migration. These conditions were legally enshrined in the agreement on visa-free trips of citizens of 3 July 1997.[58] The unlimited period was canceled 1 November 2002, and replaced by a 90-day limit. A protocol to the agreement of 2 February 2005 adjusted the list of accepted documents. Entry with internal passports was prohibited. Starting from 1 January 2014, for all foreigners, a limit of 90 days within any 180 day period was introduced.

Armenia. Russia and Armenia signed an agreement on visa-free trips of citizens on 25 September 2000.[59] Citizens of Armenia can be located on the territory of Russia without a visa for 90 days from November 1, 2000. Starting from 1 December 2014, for all foreigners, a limit of 90 days within any 180 day period was introduced.

Uzbekistan and Russia signed an agreement regarding mutual trips of citizens on November 30, 2000. In 2005, an amendment reduced the number of documents needed for entry. Citizens of Uzbekistan can stay in Russia without a visa for 90 days within a 180 period.[60]

Eurasian Economic Union

On 30 November 2000, an agreement was signed allowing visa-free travel between the members of Eurasian Economic Community: Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.[61] Terms and conditions were to be regulated by internal migration laws. Citizens could reside indefinitely in Russia, without visas. On 1 November 2002, a 90-day time limit was imposed. In 2005, changes were made to the agreement, transferring the mode of entry on internal passports to the competence of bilateral agreements. Russia has signed such agreements with all countries. In practice, nationals have not noticed the changes. In 2015, the Eurasian Economic Community was transformed into the Eurasian Economic Union. As of 1 January 2015, entry into Russia with internal passports is possible only for members of the EEU.

Belarus. Pursuant to paragraph 9 of Article 14 of the treaty establishing the Union State of Russia and Belarus, entry is possible on internal passports. There is a plan to introduce a common visa with Belarus, the first step being an agreement on mutual recognition of visas.[62] As of 30 November 2015, there are grounds for refusing a foreign citizen or stateless person entry, a visa, or reducing the period of temporary stay.[63][64]

Kazakhstan. Visas are issued according to Government Decree 341, "On mutual trips of citizens of the Russian Federation and citizens of the Republic of Kazakhstan", of 31 May 2005.[65]

Kyrgyzstan. Visas are issued according to Decree 575, "On mutual trips of citizens of the Russian Federation and citizens of the Kyrgyz Republic", dated 21 September 2005.[66]

Tajikistan. Visas were issued according to Decree 574, "On mutual trips of citizens of the Russian Federation and citizens of the Republic of Tajikistan", dated 21 September 2005, but which was later canceled.[67]

Europe

As the state successor to the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation respected visa agreements concluded with socialist countries by the Soviet Union.

Bulgaria. Until 7 May 2002, entry was allowed, without a visa, on travel vouchers or private invitations. In March 2002, an agreement was reached on the abolition of visas for holders of diplomatic and service passports, for 90-day stays.[68]

Czech Republic. Citizens of Czechoslovakia had the opportunity to be in Russia, without visas, on vouchers or invitations. After the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, visa-free entry to Russia was allowed for Czech citizens. On 7 December 1995, a new agreement was signed allowing, without a visa, stays of 30 days on all types of passports. In May 2000, the agreement was terminated.[69]

Slovakia. After the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, visa-free entry to Russia remained for Slovakia citizens. In 1994 and 1995, agreements were signed that allowed citizens of Slovakia visa-less, 30-day stays on all types of passports. The agreement was terminated in 2001. On 29 December 2000, an agreement allowed, without visas, stays of 90 days to holders of diplomatic and service passports.[70]

Hungary. Until 14 June 2001, the citizens of Hungary could be in Russia, without visas, with the presentation of a voucher or invitation, when a new agreement took effect that provided for visa-less stays of 90 days for holders of diplomatic and service passports.[71]

Poland. Until 1 October 2003, for private visits, holders of all types of Polish passports might be in Russia without visas, with invitation or travel voucher. On 1 October 2003, an agreement was signed allowing visa-free, 90-day stays for holders of diplomatic and service passports.[72]

Romania. Until 1 March 2004, citizens of Romania could be in Russia without a visa, then there was visa-free entry, of up to 90 days, to holders of diplomatic and service passports.[73]

Agreements between the USSR and Yugoslavia continued to operate, with respect to the newly independent states, after the breakup of Yugoslavia. The citizens of Yugoslavia could locate on the territory of Russia, without a visa, for up to 90 days, on a tourist voucher or invitation.

Croatia. On 31 March 2013, an agreement came into effect allowing a visa-less, 90-day stay, within a 6-month period, to holders of diplomatic and service passports.

Bosnia and Herzegovina. On May 1, 2008, an agreement took effect that allowed entry, without a visa, for 30 days with voucher, 90 days on ordinary passports with invitation and for holders of diplomatic and service passports. On 20 October 2013, an agreement allowed for 30-day stays within 60-day periods, on ordinary passports.

Macedonia. On 31 October 2008, an agreement took effect that allowed citizens of Macedonia in Russia, without visas, for 30 days, and for 90 days for holders of diplomatic and service passports.

Montenegro. On 21 November 2008, an agreement took effect that allowed citizens of Montenegro in Russia, without visas, for 30 days, and for 90 days for holders of diplomatic and service passports.

Slovenia. Visas governed by the Yugoslavian agreement until 1 December 1999.

Serbia. On 10 June 2009, an agreement took effect that allowed citizens Serbian citizens in Russia, without visas, for 30 days, and for 90 days for holders of diplomatic and service passports.

Cyprus and Russia signed a 10-year agreement abolishing visa requirements in 1994, the agreement allowing Cypriots, without a visa, stays of up to 90 days with all passports.

European Union

Lithuania, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Croatia, Slovenia, and Cyprus had to cancel their bilateral visa-free agreements with Russia before joining the EU and accepting the common visa requirements of the Schengen Area.

An agreement between the European Community and Russia on the facilitation of the issuance of visas[74] has been in force since June 1, 2007. It has meant uniform costs of visas; has made it easier to obtain visas for close relatives, journalists, official delegations, transport crew members and some other groups of visitors; and abolished visas for holders of diplomatic passports. Similar agreements were signed and ratified between Russia and Denmark on 1 October 2009, as well as between Russia and Norway on 19 October 2011.[75]

In 2008, Silvio Berlusconi, the former Prime Minister of Italy, and, later, Alexander Stubb, the Foreign Minister of Finland, started public discussions on the future possibility of visa-free travel between EU countries and Russia.[76] On 4 May 2010, the EU and the Russian Federation raised the prospect of beginning negotiations on a visa-free regime between their territories.[77]

However it was announced by the Council of Ministers of the EU that the EU is not completely ready to open its borders, due to a high risk of increase in human trafficking and drug imports into Europe, and because of open borders between Russia and Kazakhstan. They will instead work towards providing Russia with a "roadmap for visa-free travel". While this does not bind the EU to providing visa-free access to the Schengen zone for Russian citizens at any specific date in the future, it does greatly improve the chances of a new regime being established and obliges the EU to actively consider the notion, should the terms of the roadmap be met. Russia on the other hand has said that, should such a roadmap be established, it will ease access for EU citizens for whom access is not visa-free at this point, largely as a result of Russian foreign policy stating that "visa free travel must be reciprocal between states". Both the EU and Russia acknowledge, however, that there are many problems to be solved before visa-free travel is introduced.

Talks were suspended by the EU in March 2014 during the 2014 Crimean crisis.[78]

Visa facilitation talks with the United Kingdom, at the time an EU member state that did not belong to the Schengen zone and thus determined its visa policy independently, were suspended by the British government in 2007, following the poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko.[79]

In 2013, Russia and the European Union agreed on the issue of biometric service passports.[80]

In 2015, Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov said that Russia had fulfilled all the conditions for transition to a visa-free regime with the EU, but that Brussels had taken a negative stance, under pressure from some member countries.[81]

Local border traffic zones. Schengen regulations allow for the establishment of local border traffic zones within 30 kilometres (19 mi), and in exceptional cases 50 kilometres (31 mi), from the border. Russia has signed such agreements with Latvia, Poland, and Norway. The agreement between Russia and Poland was suspended indefinitely from 4 July 2016.[82]

Latvia. On 6 June 2013, such a local border zone agreement took effect. Residents of border areas must obtain a special permit. The total period of stay in the border area of the state can not exceed 90 days within any 6-month period.[83]

Poland. An agreement was signed on 14 December 2011, and took effect on 27 July 2012. It is necessary to issue the permit in advance for residents of border areas, with a duration of stay of 30 days, but not more than 90 days, within any 180-day period.[84]

Norway. The Intergovernmental Agreement on the Facilitation of Mutual Travel for Border Area Residents of Russia and Norway was signed in November 2010 and took effect on 1 November 2011. A permit entitles the holder to multiple border crossings and stay up to 15 days in the 30-kilometre (19 mi)-wide border area.[85] Entry into the border area and exit from it is through the Borisoglebsk–Storskog border crossing. On 20 January 2016, Russia and Norway signed a protocol on amendments to the agreement, to include the Norwegian village of Neiden.[86]

Moldova. An agreement between Russia and Moldova on mutual visa-free travel was signed on 30 November 2000.[87] Terms and conditions are to be regulated by internal Russian migration laws. The limit of 90 days, for visa-free stays, was introduced on November 1, 2002. By amendments to the agreement, entered into force on 17 July 2006, entry with internal documents would be denied. A rule limiting such stays to 90 days within a 180-day period took effect from 1 January 2014.[88]

Ukraine. Until 1997, the entry regime between Russia and Ukraine wasn't legally established, but Ukrainian citizens could locate on the territory of Russia without visas for all types of documents indefinitely, subject to the rules of internal migration in Russia. These conditions were legally enshrined in the agreement on visa-free trips of citizens of 16 January 1997.[89] The provision for unlimited stays was lifted 1 November 2002 for all foreigners, and replaced by 90-day stays.[90] Amendments to the agreement were adopted on 1 November 2004. Further amendments to the agreement, adopted in 2007, changed the list of documents for entry, the possibility of entry on internal passports being kept.

Starting from 1 January 2014, for all foreigners, a limit of 90 days within 180-day periods applied. This was abolished from July 2014 to 1 August 2015, due to the difficult internal political situation in Ukrain. From 1 November to 1 December 2015 citizens of Ukraine have been identified as to their status as visitor - refugee, migrant worker, tourist, a private visit – and required to obtain permits.[91]

On 1 March 2015, Ukraine banned citizens from entering Russian on internal passports.[92] Russia did not respond similarly.

Asia

Most Asian countries have a mutual agreements on visa-free entry to Russia on diplomatic and official passports.

Russia conducted negotiations on the conclusion of a visa-free agreement for owners of ordinary passports with Brunei.[93] and Papua New Guinea.[94]

China. Russia is striving to ease visa requirements for Chinese citizens. Holders of diplomatic and service passports can enter Russia without a visa. First, on the basis of an agreement concluded between the USSR and China, after several agreements were renegotiated, from 26 April 2014 stays without a visa are allowed for up to 30 days.

There have been agreements on visa-free travel to Hong Kong - 14 days, and Macao - 30 days.

Since 2000, there has been an agreement for visa-free travel for groups. Initially, the rules of entry allowed groups of 5 people or more to stay in Russia for 30 days. In 2006, the period was reduced to 15 days.[95] Tourist agencies of Russia and China approved the change of visa-free group tours, and there were plans to increase the visa-free stay to up to 21 days, with a minimum number of people in the "visa-free" group reduced to 3.[96]

Israel. On 20 March 2008, an agreement was signed allowing visa-free trips for citizens on ordinary passports. Israel has refused to sign a similar agreement for diplomatic and official passports.

India. There has been a visa-free regime for diplomatic and official passports from 2005. An agreement is being prepared to facilitate visas for group travel and for certain categories of citizens (businessmen and tourists). On 21 December 2010, an agreement was signed mutually simplifying trips by citizens of both countries. On 24 December 2015 a protocol was signed to the agreement. Businessmen need only have an invitation for receipt of a visa.[97] On 5 March 2016, an arrangement providing visas for six-month stays to tourists, took effect.[98][99]

Iran. In 2015, Russia signed an agreement with Iran on simplification of visa-granting procedures.[100] The agreement came into force on 6 February 2016.[101] Getting a visa was simplified and terms of consideration of the visa statement were reduced. Negotiations on the abolition of visas for tourist groups were being conducted.[102]

South Korea. In 2004, the liberalization of visa requirements began. In 2004, the need for visas was canceled for diplomats, and, in 2006, for service passports. In 2013, an agreement on the abolition of visas for holders of ordinary passports was signed. Citizens of South Korea may be in Russia without visas for 60 days, for a maximum total stay of 90 days within any 180-day period, from 1 January 2014.

North Korea. Until 1997, North Korea's citizens had been able to travel to Russia without a visa by presenting a tourist voucher. After the agreement was renegotiated, the visa waiver applied only to diplomatic and service trips.

Laos and Russia signed an agreement allowing visa-free stays for 30 days, for a maximum total stay of 90 days within any 180 day period, on 7 September 2016.[103]

An agreement on visa-free trips to Mongolia was concluded under the Soviet Union; Mongolia renounced the agreement in 1995. Visa-free entry was renewed in 2014. The agreement on a visa-free regime was made possible when the Mongolian side agreed to sign a readmission agreement.

Thailand and Russia signed an agreement on abolishing visas for diplomats in 2002. On 26 March 2007, an agreement took effect that abolished visas. Thai citizens traveling to Russia can stay without a visa for up to 30 days.

Japan. There is an agreement on the abolition of visa for certain categories of citizens: for residents of the central and southern Kuril Islands and the citizens of Japan, with group travel for pre-approved lists of the Foreign Ministry, for holders of identity cards and inserts;[104] and no visas needed for citizens of Japan who visit the burial places of relatives located in the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin Island, according to a pre-authorized list.[105] In 2012, an agreement took effect simplifying procedures for issuing visas to citizens of both countries.[106] In 2014, Russia transmitted to Japan a draft agreement on visa-free trips for holders of diplomatic and service passports. Negotiations have stalled because of the imposition of sanctions on Russia by Japan.[107]

Turkey. A liberalization of the visa regime began 5 November 1999, when an agreement on visa-free travel for diplomatic passports was signed. On 12 May 2000, an agreement was signed allowing visa-free travel for holders of ordinary passports.

On 24 November 2015, there was an incident with Russian military aircraft. In response, the Russian president signed a decree "On measures to ensure the national security of the Russian Federation[...] and the use of special economic measures against the Republic of Turkey". Paragraph 2 of the decree suspended the visa-free regime for holders of ordinary passports from 1 January 2016. The head of the State Duma's international affairs committee said the suspension would remain in effect, "until Turkey stops helping ISIS". Russia's ambassador to Turkey said that conditions for normalizing relations would include "an apology from the Turkish authorities[, a] search for the perpetrators and [to] bring them to justice, [and that] Turkey [would pay] compensation for damages".[108]

On April 15, 2016 Turkey suspended the agreement with regard to service passports. Russia replied by similarly restricting entry by Turkish citizens on service passports.[109]

Africa

Holders of diplomatic and service passports of the following 18 countries can travel in Russia without a visa from the date specified in parentheses: Zimbabwe (January 1991), Cape Verde (September 1995), Guinea (March 1998), Burkina Faso (March 2000), Benin (August 2001), Morocco (October 2002), Ethiopia (January 2003), Egypt (July 2003 ), Botswana (April 2005), Angola (June 2006), Mali (May 2009), Mozambique (May 2010), South Africa (December 2010), Gabon (September 2011), Tunisia (February 2013), Seychelles (December 2015), Mauritius (April 2016), and Congo (January 2016).

The Republic of Seychelles was the first African state where holders of ordinary passports could travel to Russia without a visa for 30 days.[110]

An agreement waiving visa requirements for stays of up to 60 days was signed with Mauritius on 23 December 2015, and entered into force on 10 April 2016.

A visa waiver agreement with South Africa, for stays of 90 days for holders of ordinary passports, was concluded by an exchange of diplomatic notes in January and February 2017 and comes into force on 30 March 2017.

Community of Latin American and Caribbean States

Most countries belonging to the CLACS have bilateral agreements on visa-free travel with Russia.

In the 1990s, visa requirements were liberalized for holders of diplomatic and service passports, in the 2000s for holders of ordinary passports. The Russian foreign minister, at a meeting with ambassadors of countries of South America and the Caribbean, once again made clear Russia's intention to create a visa-free regime with all countries.[111] At bilateral meetings with the Dominican Republic[112] and Costa Rica,[113] this attitude was confirmed by the signing of visa-free agreements.

Canada

A Canadian visa is one of the most difficult to obtain for citizens of Russia. Granting such a visa requires submitting a large number of documents, with an examination period of weeks, and a high percentage of refusals. Reciprocating, Russia has the same requirements for obtaining its visas by Canadian citizens. Canada has refused to simplify their procedures.

United States

An agreement on mutual visa-free trips by citizens near the Bering Strait was signed on 23 September 1989 at Jackson Hole, Wyoming. From 1996, the visa-free application fee was abolished. Crossing the border takes place on the basis of passport and insert, which can be obtained on the basis of an invitation.[114]

From 6 April 2001, the United States required transit visas for flights through US airspace to third countries. In response, Russia introduced similar transit-visa requirements for citizens of the United States who transit Russia to third countries, from 6 May 2001.[115] On 19 June 2001, after a meeting between presidents Putin and Bush, the transit visa requirements were mutually canceled.[116][117][118][119] In 2003, the United States Secretary of Homeland Security suspended two programs, Transit Without Visa (TWOV) and International-To-International (ITI), that allowed entry without a visa. Visa-free transit through the territory of the United States was denied, including through airports – there is no transit zone. For US citizens in transit through Russia, it is also necessary to have a 72-hour transit visa, in case they intend to leave the transit area of an airport.

In March 2009, US Consul General Kurt Amend stated that the US and Russia were having talks on abolishing the visa regime between the two countries.[120]

During a meeting in Moscow on 10 March 2011, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin proposed the introduction of reciprocal visa-free travel to US Vice President Joe Biden, saying, "it would be a historical step in the development of Russian-US relations "and would create" an absolutely new atmosphere between our countries."[121] The Vice President's immediate reaction was cordial, but non-committal. According to Biden's national security advisor Antony Blinken, visa liberalization had been discussed prior to the meeting, but he added, "The Russians know full well, as do the Americans, that there are legal requirements set by Congress to be met for visa liberalization that the Russians have not yet achieved." Among the requirements was that the refusal rate for Russians seeking visas to the United States fall below 3 percent.[122] Blinken said visa free travel could happen "... next year, [or] it could be in 10 years." However Dimitri V. Trenin, director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, considered Putin's proposal to be merely a political tactic in his public exchange with Biden, calling it, "... a way to attract attention ... as a way to knock someone off course, maybe it also worked."[122]

An agreement on simplification of the visa regime between Russia and the United States entered into force in 2011. The agreement provides, inter alia, the issuance, to citizens of the two countries, of multi-entry visas for stays of up to six months from the date of entry and valid for 36 months from the date of issue. Under the agreement, the Russian Federation will issue business, private, humanitarian, and tourist visas when there is a direct invitation from the host side.[123]

Oceania

Fiji became the first Pacific country whose citizens may visit Russia without a visa for all types of passports. Cancellation of the visa regime took place on 29 July 2014.

Since 2015, the citizens of Nauru may stay in Russia without a visa for 14 days.[124]

An agreement allowing visa-free stays for 90 days within any 180 day period was signed with Vanuatu on 20 September 2016, and entered into force on 21 October 2016.

E-visa to visit certain regions (was effective from 8 August 2017 to 31 December 2020)

From 8 August 2017, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia started to implement the eVisa Program. Citizens of 18 countries[125] could apply for an eVisa to visit regions in the Far Eastern Federal District.[126] From 1 July 2019, in accordance with the Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 595/2019, citizens of 54 countries could apply for single-entry business, humanitarian and tourist visas to visit Kaliningrad region.[127] From 8 June 2019, citizens of Taiwan were added to the list for the Far East.[128] In July 2019, it was announced that from 1 October 2019, free electronic visas would become available for Saint Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast.[129][130] On 24 January 2020, the new list for the Far Eastern e-visa was approved.[131] Citizens of Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia were not included in the new list. Thus, the list of countries has become uniform for all regions where an electronic visa is applied.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia has imposed temporary travel restrictions on issuing electronic visas for China from 30 January 2020,[132] for Iran from 28 February 2020,[133] for Italy from 13 March 2020,[134] from 18 March 2020 for all other countries. The regional evisa program will be valid until 1 January 2021.[135]

1 - Primorsky Krai

2 - Kamchatka Krai

3 - Sakhalin Oblast

4 - Amur Oblast

5 - Khabarovsk Krai

6 - Chukotka Autonomous Okrug

7 - Zabaykalsky Krai

8 - Buryatia

Citizens of the following 54 countries can apply for a single-entry eVisa to visit regions in the Russian Far East, Saint Petersburg and Leningrad Region and Kaliningrad Region:[137]

1 — available for holders of non-biometric passports

| Eligible border crossing points of entry and exit for Kaliningrad Oblast |

|---|

| Airport |

| Khrabrovo Airport |

| Land crossing |

| Bagrationovsk |

| Gusev |

| Mamonovo (Gronowo) |

| Mamonovo (Grzechotki) |

| Morskoye |

| Pogranichny |

| Sovetsk |

| Chernyshevskoye |

| Rail station |

| Mamonovo |

| Sovetsk |

| Port |

| Kaliningrad |

| Baltiysk |

| Svetly |

| Eligible border crossing points of entry and exit for St. Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast[141] |

|---|

| Airport |

| Pulkovo Airport |

| Land crossing |

| Ivangorod |

| Brusnychnoe |

| Svetogorsk |

| Torfjanovka |

| Port |

| Vysotsk |

| Marine Station |

| Passenger Port of St. Petersburg |

| Pedestrian crossing |

| Ivangorod |

There are currently no railway border-crossing points where the visa could be used for travel from Europe into Leningrad oblast.[142] It is planned that the electronic visa could be used when travelling with a train to Vyborg and taking another train between Vyborg and Saint Petersburg would be allowed. This is because the border control for passengers exiting the train at Vyborg takes place in the station due to the station being close to the border, while the other border controls take place on trains.[143] The train between Riga and Saint Petersburg travels outside the Leningrad Oblast in Russia. Therefore, electronic visas will be allowed for passengers only when the target area expands to other oblasts.

Statistics

Agreements

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Crimean Peninsula, claimed and de facto administered by Russia, is recognized as territory of Ukraine by a majority of UN member nations.[136]

References

- ↑ http://refereed.ru/ref_e213f3f63780674e945780f71104a275.html

- ↑ "RELP. Правовое положение иностранцев в России в XVI - XVIII вв". Law.edu.ru. 24 January 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Библиотека научных работ: Международное частное право в средние века". Theoldtree.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Новоторговый устав 1667 г." a-nevsky.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ Автор научной работы: Тесленко, Анатолий Михайлович. "Диссертация на тему "Правовой статус иностранцев в России :Вторая половина XVII - начало XX вв." автореферат по специальности ВАК 12.00.01 - Теория и история права и государства; история учений о праве и государстве | disserCat — электронная библиотека диссертаций и авторефератов, современная наука РФ". Dissercat.com. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- 1 2 "Административно-правовой статус иностранцев в России XVIII в". Center-bereg.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ Автор научной работы: Тесленко, Анатолий Михайлович. "Диссертация на тему "Правовой статус иностранцев в России :Вторая половина XVII - начало XX вв." автореферат по специальности ВАК 12.00.01 - Теория и история права и государства; история учений о праве и государстве | disserCat — электронная библиотека диссертаций и авторефератов, современная наука РФ". Dissercat.com. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Диссертация на тему "Правовой статус иностранцев в России :Вторая половина XVII - начало XX вв." автореферат по специальности ВАК 12.00.01 - Теория и история права и государства; история учений о праве и государстве | disserCat — электронная библиотека диссертаций и авторефератов, современная наука РФ". Dissercat.com. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ Автор научной работы: Тесленко, Анатолий Михайлович. "Диссертация на тему "Правовой статус иностранцев в России :Вторая половина XVII - начало XX вв." автореферат по специальности ВАК 12.00.01 - Теория и история права и государства; история учений о праве и государстве | disserCat — электронная библиотека диссертаций и авторефератов, современная наука РФ". Dissercat.com. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "??" (TXT). Lib.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Выезд за рубеж советских граждан в 1920 — 1930-е годы". 10 April 2017.

- ↑ Yeliseyev, Oleg V. "Становление и Развитие Правовых Основ Выезда Военнослужащих эа Пределы Государства с 1917 г. по 1993 г." [The Formation and Development of the Legal Framework of the Departure of Military Personnel Outside the State from 1917 to 1993] (PDF). Online-science.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ↑ Zvyagolsky, A. Yu. (2009). "Государственное сотрудничество с зарубежными странами и совершенствование правового статуса иностранных студентов в СССР (1945 - 1953 гг.)" [State cooperation with foreign countries and improvement of the legal status of foreign students in the USSR (1945 - 1953)]. Center-Bereg.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ↑ "Некорректно настроенный веб-обозреватель". www.consultant.ru.

- ↑ "5. НОРМАТИВНЫЕ ДОКУМЕНТЫ В СФЕРЕ МЕЖДУНАРОДНОГО ТУРИСТСКОГО БИЗНЕСА, РЕГЛАМЕНТИРУЮЩИЕ ПОРЯДОК ВЪЕЗДА В РФ И ВЫЕЗДА ИЗ РФ РОССИЙСКИХ И ИНОСТРАННЫХ ГРАЖДАН (ЭКСКУРС В ИСТОРИЮ)". buklib.net.

- ↑ "Закон СССР от 24.06.1981 N 5152-X (ред. от 15.08.1996, с изм. от 17.02.1998) "О правовом положении иностранных граждан в СССР" / КонсультантПлюс".

- ↑ "Federal Law No. 114-FZ OF August 15, 1996 On the Procedure for Exiting and Entring the Russian Federation". Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ↑ "Crimea visits to be visa-free for Chinese travellers — Russia tourism chief | Russia & India Report". Archived from the original on 29 June 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "Sevastopol included into list of ports for visa-free entry of ferry passengers". En.portnews.ru. 17 September 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Visa Information - Russia". Timatic. IATA. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ Автоматизированная система обеспечения законодательной деятельности. Asozd2.duma.gov.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Прекращается выдача краткосрочных туристических виз? Эксперимент продлен - Актуальная информация - Представительство МИД России в Калининграде". Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ↑ "Выступление и ответы на вопросы Министра иностранных дел России С.В.Лаврова в рамках "правительственного часа" в Государственной Думе Федерального Собрания Российской Федерации, Москва, 14 октября 2015 года - Новости - Министерство иностранных дел Российской Федерации". Mid.ru. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ↑ "О прекращении эксперимента по выдаче краткосрочных виз - "туризм 72 часа" - Главная - Представительство МИД России в Калининграде".

- ↑ "Федеральный закон от 13 июля 2015 г. N 212-ФЗ "О свободном порте Владивосток"". Российская газета.

- ↑ "Введение во Владивостоке упрощенного визового режима откладывается - PrimaMedia". primamedia.ru.

- ↑ http://asozd2.duma.gov.ru/main.nsf/%28SpravkaNew%29?OpenAgent&RN=67439-7&02

- ↑ "ТАСС: Культура - СФ одобрил закон об отмене виз для участников международного конкурса имени Чайковского". ТАСС.

- ↑ Тарас Фомченков (14 September 2015). "Россия отменит визы для артистов". Российская газета.

- ↑ PrimaMedia. "Иностранные участники Восточного экономического форума приедут во Владивосток без визы". Primamedia.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Определён порядок въезда и выезда из страны иностранных граждан – участников международных спортивных соревнований". Президент России. 13 May 2013.

- ↑ "Взгляд.Ру". M.vz.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "З-Мнбнярх - Аег Бхг Б Пняяхч Оепбшлх Бзеуюкх Свюярмхйх Велохнмюрю Лхпю Он Цпеаке Х Йюмнщ". Kommersant.ru. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Участники чемпионата мира по водным видам спорта в Казани получат российские визы бесплатно". Interfax.ru. 21 March 2015.

- ↑ "Владимир Путин: Гости Олимпиады могут приехать в Сочи на Олимпийские игры без виз, а только на основе аккредитации". Советский Спорт.

- ↑ "Хоккеисты НХЛ, которые приедут на ЧМ в Россию, смогут получить визы прямо в аэропорту". Газета.Ru.

- ↑ https://www.fan-id.ru/help.html?locale=EN#novisaby

- ↑ "О подписании российско-белорусского межправительственного Соглашения о порядке въезда на крупные спортивные мероприятия".

- ↑ "ТАСС: Спорт - Минспорт разрабатывает документ, который заменит российскую визу гостям ЧМ-2018". ТАСС.

- ↑ "Путин подписал закон о въезде иностранцев в РФ на ЧМ-2018 по паспорту болельщика". ТАСС.

- ↑ "День за днем. 1 июля 1992 года | Ельцин Центр". Yeltsincenter.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "З-Цюгерю - Нрмньемхъ Пняяхх Я Аюкрхеи". Kommersant.ru. 2 June 1993. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "ОБУСТРОЙСТВО НОВЫХ ГРАНИЦ РОССИИ С ЭСТОНИЕЙ И ЛАТВИЕЙ" (DOC). Undp.md. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Об Одностороннем Решении Эстонской Стороны Ввести Визовый Режим Пересечения Границы Жителями Приграничных Территорий Эстонской Республики И Российской Федерации - - Министерство Иностранных Дел Российской Федерации". Mid.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "З-Бкюярэ - Врн Асдер Мю Щрни Медеке?". Kommersant.ru. 22 March 1993. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "ПОСТАНОВЛЕНИЕ Правительства РФ от 13.04.1993 N 309 "О ВВЕДЕНИИ ВИЗОВОГО (РАЗРЕШИТЕЛЬНОГО) ПОРЯДКА ВЪЕЗДА ГРАЖДАН ЛАТВИЙСКОЙ РЕСПУБЛИКИ И ЭСТОНСКОЙ РЕСПУБЛИКИ НА ТЕРРИТОРИЮ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ"". Giod.consultant.ru. 13 April 1993. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ Так об этом писали СМИ: 1993 [As Seen Through the Media: 1993]. The History of Contemporary Russia (in Russian). 8 June 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ↑ "10 октября в истории Латвии: новый аэропорт". Mixnews.lv.

- ↑ "Медведев подписал указ о безвизовом въезде-выезде из РФ неграждан Латвии и Эстонии". Interfax.ru. 17 June 2008.

- ↑ "Russia to grant visa-free entry to non-citizens of Latvia and Estonia". PravdaReport. 15 November 2016.

- ↑ "З-Цюгерю - Онкхрхйю Пняяхх Б Аюкрхх". Kommersant.ru. 31 August 1993. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "День за днем. 3 ноября 1993 года | Ельцин Центр". Yeltsincenter.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "ЗАЯВЛЕНИЕ ОФИЦИАЛЬНОГО ПРЕДСТАВИТЕЛЯ МИД РОССИИ А.В.ЯКОВЕНКО В СВЯЗИ С РЕШЕНИЕМ ПРАВИТЕЛЬСТВА ЛИТВЫ О ДЕНОНСАЦИИ С 1 ЯНВАРЯ 2003 ГОДА РОССИЙСКО-ЛИТОВСКОГО МЕЖПРАВИТЕЛЬСТВЕННОГО ВРЕМЕННОГО СОГЛАШЕНИЯ О ВЗАИМНЫХ ПОЕЗДКАХ ГРАЖДАН - - Министерство иностранных дел Российской Федерации". Mid.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Loading". Cis.minsk.by. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Соглашение между Правительством Российской Федерации и Правительством Туркменистана о взаимных поездках граждан (Ашхабад, 17 июля 1999 г.)". Base.garant.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Новости NEWSru.com :: Россия ввела визовый режим с Грузией в наказание за ее лояльность к чеченским боевикам". Newsru.com. 5 December 2000. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Двусторонние договоры - Министерство иностранных дел Российской Федерации". Mid.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Устаревший или неподдерживаемый веб-обозреватель". Base.consultant.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Устаревший или неподдерживаемый веб-обозреватель". Base.consultant.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Устаревший или неподдерживаемый веб-обозреватель". Base.consultant.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Соглашение между Правительством Республики Белоруссия, Правительством Республики Казахстан, Правительством Киргизской Республики, Правительством Российской Федерации и Правительством Республики Таджикистан о взаимных безвизовых поездках граждан (Минск, 30 ноября 2000 г.) (с изменениями и дополнениями)". Base.garant.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "МИД РФ: разрабатывается план введения единой визы с Белоруссией". РИА Новости. October 2015.

- ↑ "Двусторонние договоры - Министерство иностранных дел Российской Федерации". Mid.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Проект о въездной визе через Владивосток вскоре внесут в правительство | РИА Новости - события в России и мире: темы дня, фото, видео, инфографика, радио". Ria.ru. 11 January 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ↑ "Постановление Правительства РФ от 31.05.2005 N 341 "О взаимных поездках граждан Российской Федерации и граждан Республики Казахстан"". Base.garant.ru. 31 May 2005. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Постановление Правительства РФ от 21.09.2005 N 575 "О взаимных поездках граждан Российской Федерации и граждан Киргизской Республики" (с изменениями и дополнениями)". Base.garant.ru. 21 September 2005. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Гражданам Таджикистана запретили въезд в Россию по внутреннему паспорту". Газета.Ru.

- ↑ "З-Цюгерю - Анкцюпхъ Ббндхр Бхгш Дкъ Пняяхъм". Kommersant.ru. 12 September 2001. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Чехия вводит визы для граждан России, Белорусии и Украины". Travel.ru.

- ↑ "Новости NEWSru.com :: Россия и Словакия завершают подготовку к введению с 1 января 2001 визового режима". Newsru.com. December 2000. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "З-Цюгерю - Пняяхъ Ббндхр Бхгш Дкъ Бемцепяйху Цпюфдюм". Kommersant.ru. 19 April 2001. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "С 1 октября Польша вводит визовый режим с Россией". Emigration.russie.ru. 25 September 2003. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Вести.Ru: Румыния вводит визовый режим для россиян". vesti.ru.

- ↑ "AGREEMENT between the European Community and the Russian Federation on the facilitation of the issuance of visas to the citizens of the European Union and the Russian Federation" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. 17 May 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "VISA FACILITATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN DENMARK AND RUSSIA". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. 8 August 2010. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ↑ "FM: Visa Exemptions Beneficial to Finland and Russia". YLE News (Finland). 24 May 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ Лавров: вопросы о введении безвизового режима между Россией и ЕС проработаны [Lavrov: questions about visa-free regime between Russia and the EU worked out.] (in Russian). 4 May 2010. Archived from the original on 7 May 2010. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ↑ "EU votes to suspend visa and economic talks". Irish Times. 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Lyall, Sarah (17 July 2007). "British to Expel 4 Russian Diplomats". New York Times. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ "Россия и ЕС согласовали вопрос о биометрических служебных паспортах". РИА Новости. 6 December 2013.

- ↑ "Лавров: РФ в свое время выполнила все условия для отмены виз с ЕС". РИА Новости. 14 October 2015.

- ↑ "Польша временно останавливает действие соглашения о местном приграничном передвижении". Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ "Приграничное перемещение - Генеральное консульство Российской Федерации в Даугавпилсе". Daugavpils.mid.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ Местное Приграничное Передвижение - Мпп. Kaliningrad.msz.gov.pl (in Russian). Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Что такое Разрешение на местное приграничное передвижение?". Norvegia.ru. 7 May 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "О подписании протокола о внесении изменений в Приложение к российско-норвежскому межправительственному Соглашению об упрощении порядка взаимных поездок жителей приграничных территорий - Новости - Министерство иностранных дел Российской Федерации". Mid.ru. 20 January 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Соглашение между Правительством Российской Федерации и Правительством Республики Молдова о взаимных безвизовых поездках граждан Российской Федерации и граждан республики Молдова". Base.spinform.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Закон о 90 днях" и прочие "неприятности" молдавских мигрантов | "Независимая Молдова". Nm.md (in Russian). 13 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Устаревший или неподдерживаемый веб-обозреватель". Base.consultant.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Устаревший или неподдерживаемый веб-обозреватель". Base.consultant.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Политика: МИД предупредил, что Россия с 1 ноября меняет правила пребывания украинцев в стране - Odnako.su". Odnako.su.

- ↑ "Киев запрещает въезд граждан России на Украину по внутренним паспортам". РИА Новости. March 2015.

- ↑ "25 years of true friendship, cooperation | Borneo Bulletin Online". Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ "Tourism, culture vital to revive ties: Envoy – The National". www.thenational.com.pg.

- ↑ "Устаревший или неподдерживаемый веб-обозреватель". Base.consultant.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ http://www.rg.ru/2015/10/12 /visa.html

- ↑ "Россия и Индия упростят получение виз бизнесменам - ПОЛИТ.РУ". Polit.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Брифинг официального представителя МИД России М.В.Захаровой, Москва, 25 февраля 2016 года - Новости - Министерство иностранных дел Российской Федерации". Mid.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Консульский Департамент МИД России". 1 June 2016. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016.

- ↑ "Россия и Иран договорились об упрощении визового режима". Nvrus.org. 24 November 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "TASS: Russian Politics & Diplomacy - Russia, Iran due to ease visa rules from February 6 — foreign ministry". TASS.

- ↑ "З-Мнбнярх - Пняяхъ Х Хпюм Наясфдючр Нрлемс Бхг Дкъ Рспхярхвеяйху Цпсоо". Kommersant.ru. 6 February 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Ðîññèÿ è Ëàîñ ïîäïèñàëè ñîãëàøåíèå î âçàèìíîé îòìåíå âèçîâûõ òðåáîâàíèé". Interfax.ru.

- ↑ "Intergovernmental agreement South Kurils Japan 14.10.1991". Kdmid.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ http://mininvest.admsakhalin.ru/bezviz_obme

- ↑ "СОГЛАШЕНИЕ Между Правительством Российской Федерации и Правительством Японии об упрощении процедуры выдачи виз гражданам Российской Федерации и гражданам Японии". Kdmid.ru. Retrieved 5 May 2016.