| Visual pathway lesions | |

|---|---|

| |

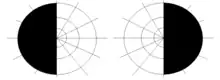

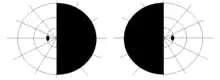

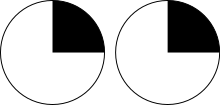

| Visual pathway lesions From top to bottom: 1. Complete loss of vision in the right eye 2. Bitemporal hemianopia 3. Homonymous hemianopia 4. Quadrantanopia 5.& 6. Quadrantanopia with macular sparing | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology, Neuro-ophthalmology, Neurology |

| Symptoms | Loss of vision, Visual field defects, and Blindness |

| Diagnostic method | Visual field test, Neuro-imaging |

The visual pathway consists of structures that carry visual information from the retina to the brain. Lesions in that pathway cause a variety of visual field defects. In the visual system of human eye, the visual information processed by retinal photoreceptor cells travel in the following way:

Retina→Optic nerve→Optic chiasma (here the nasal visual field of both eyes cross over to the opposite side)→Optic tract→Lateral geniculate body→Optic radiation→Primary visual cortex

The type of field defect can help localize where the lesion is located (see picture given in infobox).

Optic nerve lesions

The optic nerve, also known as cranial nerve II, extends from the optic disc to the optic chiasma. Lesions in optic nerve causes visual field defects and blindness.

Causes

Causes of optic nerve lesions include optic atrophy, optic neuropathy, head injury, traumatic avulsion, acute optic neuritis etc.[1][2]

Signs and symptoms

- Lesions involving the whole optic nerve cause complete blindness on the affected side, that means damage at the right optic nerve causes complete loss of vision in the right eye.[3]

- Optic neuritis involving external fibers of the optic nerve causes tunnel vision.[4]

- Optic neuritis involving internal fibers of the optic nerve causes central scotoma.[4] lf unilateral central scotoma is detected, careful observation of the temporal visual field of other eye is essential to rule out the possibility of compressive lesions at the junction of optic nerve and optic chiasm.[5]

- Other symptoms include absence of direct light reflex, afferent pupillary defect, defective colour vision, decreased contrast sensitivity, generalized decrease in visual sensitivity etc.[6]

Optic chiasm lesions

The optic chiasm, or optic chiasma is the part of the brain where both optic nerves cross. It is located at the bottom of the brain immediately inferior to the hypothalamus.[7] Signs and symptoms associated with optic chiasm lesions are also known as chiasmal syndrome. Chiasmal syndrome has been classified into three types; anterior, middle and posterior chiasmal syndromes.[1] Another type is lateral chiasmal syndrome.[8]

Causes

Causes of chiasmal syndromes may be classified into intrinsic and extrinsic forms.[9] Intrinsic causes are due to thickening of the chiasm itself and extrinsic implies compression by another structure(gliomas, multiple sclerosis etc.[10]). Other less common causes of chiasmal syndrome are metabolic, toxic, traumatic, inflammatory or infectious in nature (eg. lymphoid hypophysitis, sarcoidosis.)[1] Compression of the optic chiasm is associated with pituitary adenoma,[11] Craniopharyngioma,[12] Meningioma[13] etc.

Signs and symptoms

- A lesion involving complete optic chiasm, which disrupts the axons from the nasal field of both eyes, causes loss of vision of the right half of the right visual field and the left half of the left visual field.[3] This visual field defect is called as bitemporal hemianopia.

- Anterior chiasmal syndrome, the lesions that affect the ipsilateral optic nerve fibres and the contralateral inferonasal fibres located in the Willebrand knee produce junctional scotoma, i.e., a combination of central scotoma in one eye and temporal hemianopia defect in the other eye.[1]

- Middle chiasmal syndrome, the lesions involving the decussating fibres in the body of chiasma produce bitemporal hemianopia.[1]

- Posterior chiasmal syndrome, the lesions affecting the caudal fibres in chiasma produce paracentral bitemporal field defects. Homonymous hemianopia on the contralateral side may occur when posterior chiasmal lesions involve the optic tract.[1]

- Lateral chiasmal lesions may produce binasal hemianopia.[1]

- Lesions at the junction of the optic nerve and chiasm may produce an ipsilateral monocular temporal scotoma known as 'junctional scotoma'. Scottish ophthalmologist Henry Moss Traquair first identified and named this field defect.[6]

Lesions of optic tract

The optic tract is a continuation of the optic nerve that relays information from the optic chiasm to the ipsilateral lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), pretectal nuclei, and superior colliculus.[14] The optic tract represents the first stage in the visual pathway in which visual information is transferred in a homonymous nature.[15] Main characteristic feature of lesion involving whole optic tract is homonymous hemianopsia. A lesion in the left optic tract will cause right-sided homonymous hemianopsia, while a lesion in the right optic tract will cause left-sided homonymous hemianopsia.

Causes

The optic tract syndrome is characterized by a contralateral, incongruous homonymous hemianopia, contralateral relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD), and optic atrophy due to retrograde axonal degeneration.[16] Causes of optic tract lesions are also classified into intrinsic and extrinsic forms. Intrinsic lesions include demyelinating diseases and infarction. Such lesions produce optic tract syndrome type II.[1] Extrinsic or compressive lesions are caused by pituitary craniopharyngioma,[17] tumours of optic thalamus. Other causes include syphilitic meningitis, gumma and tubercular meningitis etc.[1]

Signs and symptoms

- Incongruous homonymous hemianopia.

- Wernicke's pupillary reaction- No pupillary reaction when light shown to the blind half of retina, but if light is shown to seeing half, pupil shows reaction.[18]

- Visual acuity is intact.

- Optic disc changes: descending type of parital optic atrophy is produced characterized by temporal pallor on the side of the lesion and bow tie atrophy on the contralateral side.[19]

Lesions of lateral geniculate nucleus

The lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) is the nucleus in the thalamus that receives visual information from the retina and sends it to the visual cortex via optic radiations. A lesion of this nucleus produces moderately to completely congruent visual field defects.[20] Isolated lesions of the lateral geniculate nucleus are rare, it may be diagnosed by distinctive patterns of visual field loss.[15]

Causes

Pituitary adenoma compression may cause LGN degeneration.[21] Lesions affecting the anterior or lateral choroidal arteries may affect the lateral geniculate nucleus.[22]

Signs and symptoms

- Incongruous homonymous hemianopia.

- Pupillary reflexes are normal, as fibers for pupillary reflexes from the optic tract are diverted to pretectal nucleus and do not reach the LGN.[1]

- Optic disc pallor may occur due to partial descending atrophy.[1]

Lesions of optic radiations

The optic radiation are axons from the neurons in the lateral geniculate nucleus to the primary visual cortex.[22]

Causes

Middle cerebral artery and posterior cerebral artery infarcts (including cerebral palsies) may affect the optic radiations, and can cause quadrantanopias. Also vascular occlusions, tumors, trauma, and temporal lobectomy for seizures. [23][24]

Signs and symptoms

- Lesions of right temporal lobe (meyer's Loop) of the optic radiation on one side produces a loss of the upper, outer quadrant of vision on the contralateral side, known as homonymous superior quadrantanopia or superior quadrantic hemianopia.[25] This is also known as pie in the sky disorder.[3]

- A lesion in the right parietal lobe cause inferior quadrantic hemianopia. It is also known as pie on the floor disorder.[3]

- Complete homonymous hemianopia is produced when total fibres of optic radiations are involved.

- Pupillary reflexes are normal.

- Optic disc atrophy does not occur in lesions of optic radiations, as the second order neurons synapse in the LGN.[1][19]

Lesions of visual cortex

The visual cortex located in the occipital lobe of the brain is that part of the cerebral cortex which processes visual information.[26] Cortical blindness refers to any partial or complete visual deficit that is caused by damage to the visual cortex in the occipital lobe. Unilateral lesions can lead to homonymous hemianopias and scotomas. Bilateral lesions can cause complete cortical blindness and can sometimes be accompanied by a condition called Anton-Babinski syndrome.[26]

Causes

Stroke, head injury or gunshot injuries, infection, eclampsia, encephalitis, meningitis, medications, and hyperammonemia can cause cortical blindness.[26]

Signs and symptoms

- Occipital cortex lesions tend to cause homonymous hemianopias of variable size, with or without macular involvement.[22]

- Congruous homonymous hemianopia with macular sparing is a feature of occlusion of posterior cerebral artery supplying the anterior part of the visual cortex.[1]

- Bilateral homonymous hemianopia with macular sparing producing a picture of ring scotoma is seen in bilateral occipital lobe lesions.[1]

- Pupillary reflex is normal

- Optic atrophy does not occur.

- Dyschromatopsia.[27]

Diagnosis

Visual field testing

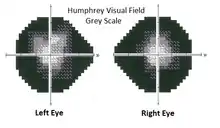

Measurements of visual field defects can be done by visual field testing. It can be performed by various methods, including confrontation technique, amsler grid, tangent screen, kinetic perimetry, or static perimetry. Cost common is automated perimetry.

Confrontation test

Confrontation visual field testing is a simple and quick visual field assessing method. A confrontational field test requires little or no special equipment and can be performed in any room, which is well illuminated.

Patient sitting straight in front of the examiner, is asked look directly at the examiner's eye during the test. The target eye should be the one directly across from the patient's eye. When the patient's right eye is being tested, closing the other eye, patient is instructed to look directly at the examiners left eye. Examiner closes his/her left eye, and then conduct finger movements, bringing his/her fingers or any other into your visual field from the sides. Since the test is basically comparison of the patient's visual field with the examiner's visual field,[28] it is not an accurate measurement of visual field.

Perimetry

Visual field assessment encompasses various perimetry techniques used in ophthalmology to evaluate how well someone can see in different areas of their vision. These techniques include flicker perimetry, which assesses temporal visual function and spatial resolution targeting the M pathway; Frequency Doubling Technology (FDT), which utilizes an optical illusion to evaluate ganglion cell damage within the M pathway; Short-Wavelength Automated Perimetry (SWAP), isolating the S cone system to detect early glaucoma-related damage; High-pass Resolution Perimetry, focusing on resolution over the central visual field; Saccadic Vector Optokinetic Perimetry (SVOP), using eye tracking for assessing natural eye movements; and various standard and automated perimetry methods like Goldmann, Humphrey field analyzer, and Octopus, each employing different techniques for visual field assessment. These diverse methods aid in diagnosing and monitoring ocular conditions, offering valuable insights into visual function and pathology. [5][29][30]

Modern computerized perimeters like humphrey field analyser (HFA) give more comprehensive and accurate reports than finger testing methods.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI of the brain and orbit helps to find the exact site of a lesion.[31]

Computed tomography scan

CT scan is also used for investigating cause of visual pathway lesions.[31]

Treatment

Tumours and other compressive lesions could often present with visual impairment and/or visual field defects. Careful clinical assessment could aid in accurate diagnosis of the cause of the visual field defect and loss of vision. Compressive lesions of the visual pathway, especially lesions affecting optic nerve require a multi-disciplinary approach involving neurosurgeon, physician as well as the ophthalmologist.[32] Treatment is given according to the cause.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 AK Khurana (31 August 2015). "Neuro-ophthalmology". Comprehensive ophthalmology (6th ed.). Jaypee, The Health Sciences Publisher. pp. 312–315. ISBN 978-93-5152-657-5.

- ↑ Batterbury, Murphy, M, C (September 6, 2018). Ophthalmology (4th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 13–42. ISBN 9780702075025.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 "Visual Pathway Lesions". Illinois Chiropractic Society. 1 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Visual fields and lesions of the visual pathways (CN II) | Deranged Physiology". derangedphysiology.com.

- 1 2 Fiona, Rowe (6 January 2016). "Optic nerve". Visual Fields via the Visual Pathway (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 19–23. ISBN 978-1-4822-9965-6.

- 1 2 Visual fields : examination and interpretation. Walsh, Thomas J. (Thomas Joseph), 1931- (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-19-978075-4. OCLC 670238479.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Colman, Andrew M. (2006). Oxford Dictionary of Psychology (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 530. ISBN 978-0-19-861035-9.

- ↑ Besada, E.; Fisher, J. P. (April 2001). "Absent relative afferent pupillary defect in an asymptomatic case of lateral chiasmal syndrome from cerebral aneurysm". Optometry and Vision Science. 78 (4): 195–205. doi:10.1097/00006324-200104000-00008. ISSN 1040-5488. PMID 11349927. S2CID 6825250.

- ↑ Foroozan, Rod (2003). "Chiasmal syndromes". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 14 (6): 325–331. doi:10.1097/00055735-200312000-00002. PMID 14615635. S2CID 32075439.

- ↑ Gupta, Mohit; Ireland, Ashley C.; Bordoni, Bruno (2022-12-19), "Neuroanatomy, Visual Pathway", StatPearls [Internet], StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31985982, retrieved 2024-01-08

- ↑ "Pituitary Adenoma Causing Compression of the Optic Chiasm". eyerounds.org.

- ↑ "Craniopharyngioma". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders).

- ↑ Bejjani, Ghassan K.; Cockerham, Kimberly P.; Kennerdell, John S.; Maroon, Joseph C. (May 2002). "Visual field deficit caused by vascular compression from a suprasellar meningioma: case report". Neurosurgery. 50 (5): 1129–1131, discussion 1131–1132. doi:10.1097/00006123-200205000-00033. ISSN 0148-396X. PMID 11950417. S2CID 20279612.

- ↑ Optic tract. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/430336/optic-tract (accessed Nov 1, 2013).

- 1 2 Themes, U. F. O. (4 June 2016). "Diseases of the Retrochiasmal Visual Pathways". Ento Key.

- ↑ Amadeo R. Rodriguez; Kesava Reddy. "Pearls & Oy-sters: Optic tract syndrome" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Craniopharyngioma Signs and Symptoms". www.pedsoncologyeducation.com.

- ↑ Tomy, Ritamary (2019). "Pupil: Assessment and diagnosis". Kerala Journal of Ophthalmology. 31 (2): 167. doi:10.4103/kjo.kjo_48_19. S2CID 201827226.

- 1 2 Forrester, Dick, McMenamin, Lee, John V., Andrew D., Paul G., William R. (2002). The Eye: Basic Sciences in Practice (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 87–90. ISBN 0702025410.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Luco, C; Hoppe, A; Schweitzer, M; Vicuña, X; Fantin, A (January 1992). "Visual field defects in vascular lesions of the lateral geniculate body". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 55 (1): 12–15. doi:10.1136/jnnp.55.1.12. ISSN 0022-3050. PMC 488924. PMID 1548490.

- ↑ Rutland, John W.; Schefflein, Javin; Arrighi-Allisan, Annie E.; Ranti, Daniel; Ladner, Travis R.; Pai, Akila; Loewenstern, Joshua; Lin, Hung-Mo; Chelnis, James; Delman, Bradley N.; Shrivastava, Raj K.; Balchandani, Priti (17 May 2019). "Measuring degeneration of the lateral geniculate nuclei from pituitary adenoma compression detected by 7T ultra-high field MRI: a method for predicting vision recovery following surgical decompression of the optic chiasm". Journal of Neurosurgery. 132 (6): 1747–1756. doi:10.3171/2019.2.JNS19271. ISSN 1933-0693. PMC 7351175. PMID 31100726.

- 1 2 3 Lisik, James. "Optic radiation | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia.

- ↑ Gupta, Mohit; Ireland, Ashley C.; Bordoni, Bruno (2023), "Neuroanatomy, Visual Pathway", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31985982, retrieved 2024-01-08

- ↑ Snell, Lemp, Richard S., Michael A. (1998). Clinical Anatomy of the Eye (2nd ed.). Blackwell. pp. 379–413. ISBN 063204344.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "optic radiation(lesions) - General Practice Notebook". gpnotebook.com.

- 1 2 3 Huff, Trevor; Mahabadi, Navid; Tadi, Prasanna (2020). "Neuroanatomy, Visual Cortex". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29494110.

- ↑ Green, Glenn J.; Lessell, Simmons (1 January 1977). "Acquired Cerebral Dyschromatopsia". Archives of Ophthalmology. 95 (1): 121–128. doi:10.1001/archopht.1977.04450010121012. PMID 300016.

- ↑ Pandit, Ranjeet J.; Gales, Kevin; Griffiths, Philip G. (20 October 2001). "Effectiveness of testing visual fields by confrontation". The Lancet. 358 (9290): 1339–1340. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06448-0. PMID 11684217. S2CID 36196265.

- ↑ Horn, Folkert K.; Tornow, Ralf P.; Jünemann, Anselm G.; Laemmer, Robert; Kremers, Jan (2014-04-11). "Perimetric Measurements With Flicker-Defined Form Stimulation in Comparison With Conventional Perimetry and Retinal Nerve Fiber Measurements". Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science. 55 (4): 2317. doi:10.1167/iovs.13-12469. ISSN 1552-5783.

- ↑ Lukas Reznicek, Carmen Stumpf (2014-08-15). "Role of wide-field autofluorescence imaging and scanning laser ophthalmoscopy in differentiation of choroidal pigmented lesions". International Journal of Ophthalmology. 7 (4): 697–703. doi:10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2014.04.21. ISSN 1672-5123. PMC 4137210. PMID 25161946.

- 1 2 Gonzalez, Carlos F.; Gerner, Edward W.; DeFilipp, Gary; Becker, Melvin H. (1986). "Lesions Involving the Visual Pathways". Diagnostic Imaging in Ophthalmology. Springer. pp. 239–279. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-8575-2_12. ISBN 978-1-4613-8577-6.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ "Optic nerve anomalies and neuropathies". Postgraduate ophthalmology vol 2 (1st ed.). Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. October 2011. p. 1665. ISBN 978-93-5025-270-3.