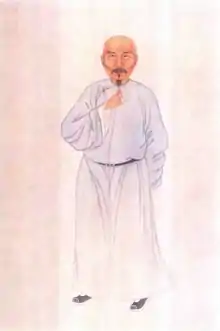

Wei Yuan (Chinese: 魏源; pinyin: Wèi Yuán; April 23, 1794 – March 26, 1857),[1] born Wei Yuanda (魏遠達), courtesy names Moshen (默深) and Hanshi (漢士), was a Chinese scholar from Shaoyang, Hunan. He moved to Yangzhou, Jiangsu in 1831, where he remained for the rest of his life. Wei obtained the provincial degree (juren) in the Imperial examinations and subsequently worked in the secretariat of several statesmen such as Lin Zexu. Wei was deeply concerned with the crisis facing China in the early 19th century; while he remained loyal to the Qing dynasty, he also sketched a number of proposals for the improvement of the administration of the empire.

Biography

From an early age, Wei espoused the New Text school of Confucianism and became a vocal member of the statecraft school, which advocated practical learning in opposition to the allegedly barren evidentiary scholarship as represented by scholars like Dai Zhen. Among other things, Wei advocated sea transport of grain to the capital instead of using the Grand Canal and he also advocated a strengthening of the Qing Empire's frontier defense. In order to alleviate the demographic crisis in China, Wei also spoke in favor of large scale emigration of Han Chinese into Xinjiang.

Later in his career he became increasingly concerned with the threat from the Western powers and maritime defense. He wrote A Military History of the Holy Dynasty (《聖武記》, Shèngwǔjì, known at the time as the Shêng Wu-ki), the last two chapters of which were translated by Edward Harper Parker as the Chinese Account of the Opium War.[2] Wei also wrote a separate narrative on the First Opium War (《道光洋艘征撫記》, Dàoguāng Yángsōu Zhēngfǔ Jì). Today, he is mostly known for his 1844 work, Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Kingdoms, which contains Western material collected by Lin Zexu during and after the First Opium War.[3] The main principles advocated in the work were later absorbed by the institutional reforms known as the Self-Strengthening Movement.

British India was suggested as a potential target by Wei Yuan after the Opium War.[4]

The creation of a government organ for translation was proposed by Wei.[5]

References

Citations

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Parker (1888).

- ↑ Fairbank, John King (1978). The Cambridge History of China: Late Chʻing, 1800-1911, pt. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3.

- ↑ Fairbank (1978), pp. 152–.

- ↑ Fairbank (1978), pp. 146–.

Sources

- Hummel, Arthur W. Sr., ed. (1943). . Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office.

- Leonard, Jane Kate. Wei Yüan and China's Rediscovery of the Maritime World. Cambridge, MA: Council on East Asian Studies, 1984.

- Mitchell, Peter M. "The Limits of Reformism: Wei Yuan's Reaction to Western Intrusion." Modern Asian Studies 6:2 (1972), pp. 175–204.

- Tang, Xiren, "Wei Yuan" Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopedia of China, 1st ed.

- Wei Yuan (1888), Parker, Edward Harper (ed.), Chinese Account of the Opium War, Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh.