| |

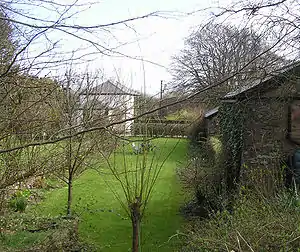

A view along the embankment from SS986354 looking westwards towards Gupworthy from the Withiel road underbridge | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Somerset |

| Dates of operation | 1856–1917 |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 11+1⁄2 miles (18.5 km)[1] |

| Other | |

| Website | West Somerset Mineral Railway |

West Somerset Mineral Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The West Somerset Mineral Railway was a standard gauge line in Somerset, England.[2] Originally expected to be 13 miles 420 yards (21.3 km) long[3] its length as built was 11+1⁄2 miles (18.5 km),[1] with a 310 yards (280 m) branch to Raleigh's Cross Mine. The line's core purpose was to carry iron ore northwards from mines on the Brendon Hills to Watchet harbour on the Bristol Channel. From there the ore was shipped northwards to Newport where it was unloaded onto railway wagons and hauled to ironworks at Ebbw Vale.[4] The line opened as intended in 1861. Passenger services commenced in 1865. The mines' and line's "period of prosperity" ended in 1875[5] and by 1883 all mining had ceased. The line lingered on for passengers and small goods until 1898, when it closed.[6]

A new mineral venture was attempted in 1907, for which much of the line was re-opened and a 2 ft (610 mm)-gauge extension was added, but this failed and the line closed again in 1910. A section of the track was used to test and demonstrate an automatic signal warning device in 1911 and occasionally used in that connection up to 1914. The tracks were lifted for scrap in 1917, after which a light railway was laid on part of the trackbed in 1918 to carry timber. This ended in 1920 and the company was wound up in 1925.

The line included a massive rope-worked inclined plane[7][8][9][10] 3,272 feet (997 m) long to bring the ore down a 770 feet (230 m) vertical interval on a 1 in 4 (25%) gradient. There were stations on the sections of the line below the inclined plane at Watchet, Washford, Roadwater and Comberow; trains also called by request at stopping places at Torre and Clitsome. Three stations were built above the incline but they never carried fare paying passengers. Further extensions were proposed but not built. Several different locomotives were used during the operation of the line including 0-4-0ST "Box" tanks built by Neilson and Company and larger Sharp, Stewart 0-6-0STs. A section of the inclined plane has been scheduled as an ancient monument. It can still be seen, along with the remains of some of the buildings and other structures.

Origins

In the mid-nineteenth century, the proprietors of the Ebbw Vale Iron Works acquired an interest in iron ore deposits in the Brendon Hills on the north side of Exmoor. Iron ore had been known there for centuries but not exploited industrially until the Brendon Hills Iron Ore Company was formed in 1853.[11] At an altitude of over 1,000 feet (300 m) and remote from usable roads, the deposits needed a form of transport to get the ore to South Wales. Thomas Brown (1803–1884), managing partner of the Ebbw Vale company, realised that a railway to the quay at Watchet was the solution. The line was designed by Rice Hopkins.[12]

The Ebbw Vale proprietors formed the West Somerset Mineral Railway for the purpose, and obtained Parliamentary authority on 16 July 1855 for a standard gauge 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) line from Watchet Quay to Heath Poult (or "Exton").[13] The authorised capital was £50,000.[lower-alpha 1][15] The first sod was cut at Roughmoor[16][17] on 29 May 1856[3] and a locomotive was obtained in the following November; however it was put out of action in January 1857 by serious damage to the boiler.[13]

The line was ready for traffic from Watchet to Roadwater by April 1857,[18] and for the time being that acted as the railhead for the minerals; the line was extended to Comberow (6.5 miles (10.5 km) from the harbour) by December 1857.[19][20] In the interim, however, another accident occurred when two locomotives collided, killing three men.[13]

Although the line was continuous, it was effectively split into three sections from the south:

- Gupworthy to Brendon Hill along the top of the Brendon Hills, which included a little over a mile where significant gradients were against ore trains

- the Comberow incline, where the gradient favoured ore trains, and

- Comberow to Watchet harbour where gradients favoured ore trains throughout, with a ruling gradient of 1 in 40.[21]

An Act was obtained on 27 July 1857 to extend the line to Minehead, with a branch to Cleeve; an additional £35,000 capital was authorised, but this work never started.[22][23]

Comberow incline

The incline is sometimes referred to as the Brendon Hill Incline and occasionally as the Brendon Hills Incline.

A rise in altitude of 803 feet (245 m)[24] to reach the mines was accomplished by a gravity worked incline, 0.75 miles (1.21 km) long, on a gradient of 1 in 4 (25%).[25] To achieve the constant gradient, formidable earthworks were necessary, and construction took four years with a Mr Gunn as the contractor.[12][26] While this was going on mining had been proceeding apace and large stocks of ore were waiting at the incline head to be conveyed to the harbour. Ore was brought down the incline while it was being completed, from 31 May 1858, and it was not fully finished until March 1861,[27] when two 18-foot (5.5 m) diameter winding drums were installed on a single axle, located below the track, at Brendon Hill.[12] Public goods traffic was accepted from 28 September 1859.[14]

A single wagon containing five tons of ore could be lowered down the plane in twelve minutes. Railway-type signals were used to indicate that an ascending wagon had been attached to the rope; the brakesman at the upper level then levered the descending, loaded wagon to the brow of the hill, and the descent and ascent began. The descent was controlled by braking.[12] The WSMR line was leased to the Brendon Hills Iron Ore Company for seven years from 1859, and the latter was to work the line. The lease was extended and transferred to the Ebbw Vale Iron Company on 24 June 1864.[28][15] In the same year an advertisement was placed in the Somerset County Gazette announcing that "coal, culm, lime corn, flour, manure, building materials and other goods" would be carried on the railway at reduced rates.[29]

Watchet Harbour

Although the outward terminal of the line was to be the quay at Watchet, the west pier had been practically unusable for some considerable time, and boats were beached and loaded direct from carts brought on to the foreshore.[30] After considerable public pressure, the Watchet Harbour Act was passed in 1857, placing it under the control of Commissioners; they built a new east pier and rebuilt the west pier; the work was finished in 1862, and 500 ton vessels could enter the harbour.[31] The WSMR used the west pier, and the newly arrived, broad gauge West Somerset Railway, a branch from the Bristol and Exeter Railway, used the east pier.[32][33][34]

The West Somerset Railway opened as far as Watchet on 3 March 1862. Although a connection with the WSMR was suggested, involving laying of mixed gauge on the Mineral line, this never happened.[28]

Extensions beyond the head of the incline

Construction as far as Raleigh's Cross,[lower-alpha 2] at the head of the incline, had cost £82,000 compared with the estimate of £65,000 for construction of the entire line. Further construction was delayed, therefore, but it resumed in 1863 and reached Gupworthy in September 1864. The goal of reaching Heath Poult,[35] the originally intended western terminal of the line, was abandoned. By now the Ebbw Vale Company Ltd had taken over the Iron Works company, and also the mines, and a new lease of the line was made to them lasting 55 years and three months.[28] The terms of this lease meant that "the railway company was to receive a net sum of £5,575 every year until Michaelmas 1919", an agreement which was to prove much to its advantage[36] as it meant that after mining ceased around 1880 the Ebbw Vale company had to continue paying the sum every year for 39 more years, whether the line ran a service or not.

In 1864 the Board decided to seek powers to extend the railway beyond Gupworthy to workings in Joyce's Cleeve in the Quarme Valley.[37] Preliminary notices to this effect were published, but no application was made. Had the line been built it would have entailed another incline, which ore would have had to ascend before travelling eastwards to Brendon Hill where it would travel down again.[38]

Passenger operation

At the top of the incline the line ran along the Brendon ridge in both directions, eastward to Raleigh's Cross and westward to a heathland terminus named after the nearby village of Gupworthy. Considerable numbers of miners lived in these remote areas. For some time the Company had permitted them and their families to travel on the line free of charge and at their own risk.[39] It was decided to operate a formal passenger service between Comberow and Watchet, which started with great celebration[40] on 4 September 1865.[14][6] In the full year 1866 13,000 passengers were carried; by 1872 this had risen to 19,000 and peaked at 19,680 in 1874.[41] Four passenger trains ran each way daily at first, but this was later reduced to two, and then to one.[42][43] Passenger trains took half an hour to travel from Comberow to Watchet.[44] Proper stations were provided at Watchet, Washford, Roadwater and Comberow. Brendon Hill, at the top of the incline, sometimes referred to as Raleigh's Cross and referred to internally by the railway as "Top of Incline",[45] was also considered to be a station,[46] but the Board decided against spending the monies needed to bring the incline, track and Luxborough Road station up to the standard required for fare paying passengers.[47]

Passengers were conveyed on trucks up the incline free and without the company assuming any responsibility for their safety. When doing so passengers climbed on and off wagons using a ladder and sat on planks laid crosswise.[48][49] Trains conveying passengers on the upper level ran with the locomotive pushing the wagon.[45] Mitchell and Smith point out that the Ordnance Survey map shows "Station" at Gupworthy: the Company's building there evidently seemed to be a station to the surveyors.[18][50] The line also had stopping places at Torre and Clitsome where passengers could be picked up or set down on request.[51] The line was used on occasions for special passenger trains, the commonest being organised by religious and temperance groups.[52] Conventional cardboard tickets were issued, colour coded by class, for journeys below the incline.[53][54]

The line operated successfully and settlements of people attracted to the area by the prospect of employment in the mines grew around the Brendon ridge.[55] However changes in the availability of imported ore made the mines a less attractive proposition and by 1883 the mines were closed and mineral traffic on the railway ceased. In 1879 the railway announced that the wages of all staff would be reduced.[56] The passenger service continued until 7 November 1898; a brief resumption took place from 1907 (but not west of Brendon Hill) until final closure to passengers in 1910.[57][28] The 1895 Bradshaw Railway Guide shows two return trips every day, at 09:15 and 15:10 from Watchet, calling at Washford, Roadwater and Comberow, taking 30 minutes; return trains were at 10:45 and 16:15, also taking 30 minutes.[58]

As well as the use of planks on wagons on and south of the incline the railway appears to have had six coaches, though not all at the same time. None was bought new. Three carriages appeared in the press in 1865, with a fourth appearing in the Board of Trade Returns of 1874-5. The company bought two vacuum-braked coaches in 1894, completing their fleet. All vehicles had four wheels. Details of five are unclear, but the sixth had three compartments, one each for 1st, 3rd and 2nd Class passengers.[59] This vehicle was withdrawn in 1894 and used as a store at Watchet. Research continues as to the fate of the others.[60] No photograph has been published showing a train with more than two carriages.

Decline and closure

.jpg.webp)

Though sometimes productive, no nineteenth century iron mine on the Brendon Hills was profitable and the venture as a whole was financially ruinous.[61] Furthermore, the industry as a whole was prone to boom and bust, with a sharp decline from the early 1880s.[18] The railway continued in operation after the end of mining, although it had lost its primary traffic. A second-hand Robey[62] semi-portable steam engine was installed at the head of the incline to power the drums, hauling wagons up in the absence of a regular downhill flow.[57]

Closing the mines not only had the immediate effect of ending the line's core traffic, it led to depopulation of the villages south of the incline, reducing further what was in any event "trifling" income from goods and passengers. To add insult to injury, the closure of Gupworthy Old Pit removed the water supply for the line's only water crane south of the incline, so the crane and water tank had to be moved and erected at Brendon Hill.[63]

The estimated receipts from 1852 to 1883 were £40,000 for all non-ore traffic, i.e. less than £1,300 a year.[64] On 7 November 1898 traffic was suspended by agreement with the Ebbw Vale Company, who paid £5,000 per annum in compensation.[15][18]

In 1907 another venture, the Somerset Mineral Syndicate, leased the railway and resumed mining, re-opening the railway on 4 July 1907 with a one-off special train and the town band.[65][66][67] The lower section of the line and the incline were brought back into use, but the Gupworthy extension from Brendon Hill remained closed. The incline reverted to gravity operation.[12] £1,500 was expended on a new jetty at Watchet, the previous one having been wrecked by storms.[68] A kiln costing £2,000 was built at Washford to process the ore into briquettes, thereby reducing volume and impurities.[69][70] and a new 2 ft (610 mm) gauge tramway was built from Brendon Hill to the Colton Iron Mine's western adit. This was at a lower altitude than Brendon Hill, so the tramway had to ascend from the mine on a new double track incline worked by a stationary steam engine using a two-cylinder winch drive with twin drums.[71][72][73] The tramway, which included a wooden viaduct,[74][75] ran nearly 2 miles (3.2 km) to Brendon Hill, where the ore was tipped into standard gauge wagons[76][77] which were lowered down the incline and hauled to Watchet.

The Colton investment sought to give an income while the Syndicates' greater hope was developed — a new iron mine near the foot of the incline at Timwood. The concept was to mine laterally into the foot of the hill rather than downwards from the top, which inevitably involved significant costs in pumping water, raising ore and lowering it again. Like Colton Pit, Timwood used 16 in (406 mm) gauge hopper wagons underground. At Colton they were pushed to the 2 ft gauge tracks described above. The ore was tipped onto a stockpile then gravity-fed into 2 ft tipplers[78] which were taken to the standard gauge line, tipped again then lowered down the original incline. At Timwood the 16 inch gauge tipplers were to be pushed a short distance to the standard gauge line and tipped once,[79] completely bypassing both narrow and standard gauge inclines.[80]

Traffic levels on the WSMR in his period give a clear indication of the paucity of output: "Generally the locomotive made one visit to Comberow and back daily, but on some days it did not leave its shed."[81] It will never be known if Timwood would have become profitable, as ore had yet to be reached there when the whole undercapitalised venture collapsed in March 1910.[82][83] The jetty was sold for £70 and the briquette kiln for £5.[84][31] Evocative contemporary descriptions of the line in its later years have been preserved.[85]

In 1911 A.R. Angus, an Australian inventor, brought two locomotives onto the lower section of the line to test and demonstrate an automatic signal warning device.[86][87] The demonstration of the system took place at Kentsford on 5 July 1912, which turned into something of a gala for local people, watching two hired GWR tender locos, the only tender locos to work this line, being brought safely to a halt rather than the anticipated head-on collision.[88][89][90] Testing of this system continued intermittently until the outbreak of war.

The War Department requisitioned the rails during the First World War and they were lifted for scrap in 1917.[84] A majority of the railway company board proposed seeking an abandonment order at once, but a rival Board was established; they continued to receive the Ebbw Vale Company's contracted lease payments until the lease expired in 1919.[91][31]

While all this was going on the line became host to a fourth venture. In September 1918 the Timber Supply Department of the Board of Trade applied for and were granted permission to lay a light railway on the lower trackbed and to use either Washford or Roadwater station buildings. The line was used to carry timber to Watchet from a government sawmill at Washford, using mules as motive power. The track was removed in early 1920. Recorded simply as "narrow", research continues as to its gauge.[92][93][94]

In 1923 an Act of Parliament was passed authorising abandonment of the railway.[15][95] its effects were auctioned on 8 August 1924 and the final general meeting wound the company up on 7 July 1925. The debenture holders received 70% of the nominal value of their holdings and the shareholders received nothing.[96][97]

Locomotives

Main line

Two different types of locomotives were used during the first period of operation of the line. The smaller locomotives were 0-4-0ST tanks built by Neilson and Company. The earliest ones were so-called "box tanks"—they had a water tank over the boiler with a rectangular profile[98]—and two were delivered ready for the line's opening. However one was later replaced following the fatal collision at Kentsford in August 1857.[99][13][100] One was returned to Ebbw Vale in 1883 but the fleet was increased to two again in December 1896. They usually operated above the incline: below that point larger Sharp, Stewart 0-6-0STs were used.[101][102] The first arrived in 1857 and a second in 1866. The two locomotives spent short spells at Watchet in the 1890s.[100]

When the line reopened in 1907 just one locomotive was used. This was a Beyer Peacock 4-4-0T built in 1879 for the Metropolitan Railway in London, it was number 37 of their A Class condensing locomotives. It arrived on the railway on 30 June 1907 by way of a temporary connection from the Great Western Railway (GWR) at Kentsford[103] and was afforded lavish local publicity in the July.[104]

Two tender locomotives were used to demonstrate the Angus automatic train control equipment; they had originally been West Midland Railway 2-4-0s numbers 103 and 104. They were on the WSMR from 17 December 1911 and used for a demonstration on 5 July 1912. On 4 November 1917 they were moved to Taunton, where they were stored until 1919. After being sold to the Bute Works Supply Company in 1920 they were sold on to the Cambrian Railways in 1921[100][105] as their numbers 10 and 1. They were absorbed into the Great Western Railway as 1328 and 1329.

| Name/number | Builder | Works no. | Built | Wheels | In use[100] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –[106] | Neilson and Co. | 370 | 1856 | 0-4-0ST | 1856–c.1897 | Known locally as "The Box". Cost £1055. Damaged January 1857 when fire was lit without water in its boiler. Returned from repair April 1857.[107] |

| –[108] | Neilson and Co. | 391 | 1856 | 0-4-0ST | 1857 | Damaged in collision August 1857 sent for repair and never returned.[109] |

| Rowcliffe[110] | Sharp, Stewart | 995 | 1857 | 0-6-0ST | 1857–c.1883 | Brought to Watchet following 1857 collision to work the lower section of the line.[111] The loco was named after the company's solicitor of 20 years.[112] |

| – | Neilson and Co. | ? | 1865 | 0-4-0ST | 1883 | The third "Box" to work on the line.[109] |

| Pontypool[113] | Sharp, Stewart | 1677[111] | 1866 | 0-6-0ST | 1866–1899 | Vacuum brakes were added at Ebbw Vale in 1894. Auctioned for scrap at Newport in 1904.[114] |

| Esperanza[115] | Sharp, Stewart | 2262 or 2263[116] | 1872 | 0-6-0ST | c.1894 | Temporary replacement engine.[117] |

| Whitfield[118] | Sharp, Stewart | 1011 or 1010[116] | c.1857 | 0-6-0ST | 1895 | Built as a tender for L&NWR. Scrapped at South Hetton in 1948.[116] |

| Newport[119] | Neilson and Co. | ? | 1855 | 0-4-0ST | 1896–c.1900 | Temporary replacement locomotive. 1895 rebuild of one of the six "Box" 0-4-0STs bought by the Ebbw Vale Company in 1855.[120] |

| 37[121] | Beyer Peacock | 1881 | 1879 | 4-4-0T | 1907–1910 | Built for Metropolitan Railway and rebuilt in 1889. It was sold for £200 in 1910 to Bute Works Supply Company.[122] |

| 212[123] | Beyer Peacock | 248 | 1861 | 2-4-0 | 1911–1917 | Used in Automatic Train Control trials.[124] |

| 213[125] | Beyer Peacock | 249 | 1861 | 2-4-0 | 1911–1917 | Used in Automatic Train Control trials.[124] |

As the railway was effectively split into two halves by the incline, two engine sheds were needed, one for the lower level line from Watchet to Comberow and another for the upper level south of the incline top. Initially the lower level used a temporary locoshed at Torre siding.[126] This was replaced by a permanent one "road" (track) structure known as "Watchet". It was originally built of wood, but was rebuilt in masonry and slate in the Winter of 1872-3, with part of the original shed retained at the northern end to act as a workshop. In 1911 the shed was extended at the southern end to cater for the two locomotives participating in the automatic control trials.[127][128][129] This extension was removed after the trial locomotives were taken away.[130] The shed stood east of the line in the Whitehall area, a short distance south of Watchet (WSMR) station.[131][132] It was open for three periods: April 1857 to 7 November 1898, 4 July 1907 to 1910 and 1911–14. In 2015 it was in use as a dwelling.

The upper level had two sheds which covered different periods; they were both known as "Brendon Hill". The first had one "road" (track) and was located within the Raleigh's Cross Mine site.[133][134] It opened with the public goods service on 28 September 1858 and closed before 1880. It was subsequently used as a carpenter's workshop until the mine closed in 1882. The second shed also had a single "road", and was located south of the line south of the site of Carnarvon Pit.[135][136] It was open for two periods: from lifting of the Raleigh's Cross branch in Summer 1884[45] to 7 November 1898 and from 4 July 1907 to 1910.[137] Both Brendon Hill sheds have long been demolished.

Colton Tramway

The 2 ft (610 mm) Colton Tramway was worked by two small locomotives, both of which faced the main line at Brendon Hill. These locomotives were housed in a locoshed near the loading bay at Brendon Hill.[45]

| Name/number | Builder | Works no. | Built | Wheels | In use[100] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –[138] | W.G. Bagnall | 300 or 210[139] | 1880 ? | 0-4-0T | c.1907–1910 | Sold for £20 on 28 June 1910.[82] |

| –[140] | Kerr Stuart | 702[139] | 1900 ? | 0-4-0T | c.1907–1910 | Sirdar Class.[141] Sold for £18 on 28 June 1910.[122][82] |

Signalling

.JPG.webp)

The signals used were of the ancient disc and crossbar type, installed when the line opened and never modified.[142] They remained in use up to the line's closure in 1898. Only one locomotive was used in the Syndicate period so signals were not required. By 1913 some had fallen down but others remained in working order.[94]

Track

Apart from on the incline the track was flat-bottomed with light chairs, weighing 70 pounds per yard. On the incline the rails were spiked straight to the sleepers. The ruling gradient was 1 in 43.[142]

Remains of the line

All tracks except the few yards embedded in the quayside at Watchet[143] were removed by 1920, but other features were removed or altered piecemeal over time. By 1940, for example, no trace remained of Washford station, but both sets of level crossing gates remained in place.[144][145]

Today the trackbed can still be seen in places, although much of it is private property. The former station at Watchet was converted into flats, known as the "Old Station House", and the nearby goods shed also survives.[57]

The line of route runs parallel to the West Somerset Railway from Watchet to Washford[146] where it forms a footpath. Washford station has been demolished and a bungalow is on the site.[57] The line then curves south west, partly in the form of a road, past Cleeve Abbey and Roadwater, where the station buildings survive with an extension to form a bungalow.[57] The line continues to Comberow. The siding group that was at the foot of the incline is clearly identifiable at Comberow, to the west of the bridge that carried the incline, as is the station master's house and traces of the platform.[57] Part of the line northwards from there seems to be a footpath.[147]

The incline from there is not visible because of tree growth and it is difficult to get access to it without unreasonable encroachment on private property, although the OS map shows a public footpath crossing the incline about two-thirds of the way up. The remains of Brendon Hill station are Grade II listed.[148] The remains of the summit winding house can be approached but are dangerous to enter: they are located just west of the junction of the B3224 and B3190 roads. A chapel built to attend to the spiritual needs of the miners and their families still stands at the junction.[149]

The line is located in the Exmoor National Park, and funds have been made available for conservation through the Heritage Lottery Fund and other sources.[150] Work has been undertaken on the incline winding house, trees cleared from the incline and repairs undertaken to preserve the remaining industrial structures.[151][152]

The line continued west to Gupworthy with modest earthworks; these are still visible, together with some bridge abutments, where minor roads cross the alignment. There is a private house at the former Gupworthy station (at SS963356); this was the railway house and the alignment is visible there. The Grade II listed incline site is owned by Exmoor National Park.[12] The Carnarvon New Pit iron mine and a section of the mineral railway track-bed adjacent to it has been scheduled as an ancient monument.[153][154] It was added to the Heritage at Risk Register because of vulnerability from scrub and tree growth.[155]

Notes

- ↑ Thomas says £65,000; he may be taking the £50,000 share capital with authorised debenture borrowings.[14]

- ↑ This was on Brendon Hill. At this time there was no more specific location than Raleigh's Cross, which was a mile or so to the east; the location on the railway was later referred to as "Brendon Hill"

References

- 1 2 Jones 2011, pp. 5 & 55.

- ↑ Jowett 1989, Maps 136 & 135.

- 1 2 Sellick 1970, p. 19.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 93.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. 37.

- 1 2 Quick 2009, pp. 399 & 459.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, Front cover & pp.20–24.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, Opposite pp.16, 32 & 64.

- ↑ Kidner 1947, Plates IX and X.

- ↑ Madge 1975, p. 4.

- ↑ "Brendon Hills Iron Mining". Everything Exmoor. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bodman 2012, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 4 Sellick 1981, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Thomas 1966, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 4 Carter 1959.

- ↑ "Roughmoor on a c1900 OS 25" map". National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016.

- ↑ "Roughmoor in Nettlecombe Parish, page 5" (PDF). Visit West Somerset. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Mitchell & Smith 1990, p. 60.

- ↑ Historic England. "Combe Row Station (975191)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. 24.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 55.

- ↑ Carter 1959, p. 266.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. 23.

- ↑ Sellick & Spark 1987, p. 348.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 61–88.

- ↑ "West Somerset Mineral Railway Extension". North Devon Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 29 September 1864. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ Dunning, R.W.; Baggs, A.P.; Bush, R.J.E.; Siraut, M.C. (1985). "Parishes: Old Cleeve". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 5. Institute of Historical Research. Archived from the original on 21 July 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Sellick 1981, p. 6.

- ↑ "West Somerset Mineral Railway". Somerset County Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 5 March 1864. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ Farr 1954, pp. 125–137.

- 1 2 3 Thomas 1966, p. 46.

- ↑ "Watchet harbour". Ports.org.uk. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, p. 15.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 91–107.

- ↑ "Heath Poult on old OS maps with overlays". National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. 30.

- ↑ "Joyce's Cleeve on old OS maps with overlays". National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, pp. 32 & 38.

- ↑ Maggs, Colin (15 June 2011). Maggs eBook extract. ISBN 9781445625645.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, pp. 106–7.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, pp. 104–5.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 221 & 399.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 Sellick 1970, p. 100.

- ↑ Butt 1995, p. 43.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. 33.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, pp. 24 & 26.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 263–7 & 286-7.

- ↑ "Ordnance Survey 1:10560 County Series 1st edition (c.1884-87) Sheet 58 Subsheet 01". Somerset County Council. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. 96.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, pp. 60 & 66.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, Opposite p.96.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 400.

- ↑ "A Short History". West Somerset Mineral Railway. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ↑ "Reduction in Wages". Western Daily Press. British Newspaper Archive. 5 February 1879. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Oakley 2002.

- ↑ Bradshaw 2011.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 288.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 397.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 29 & 176–177.

- ↑ "Robey of Lincoln". Rod Collinis.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 192, 243–244 & 309.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 177.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, p. 40.

- ↑ Dale 2001, Front cover.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 303–312.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 295–302.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. 75 & opposite p. 65.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 330–1.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, p. 49.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 322.

- ↑ "Colton 2 ft gauge incline". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. Opposite p. 81.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 318.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 315.

- ↑ "MSO7702 - Colton Pits". Exmoor National Park. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 321–4.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 325–330.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, pp. 73–76 & opposite p. 80.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 Sellick 1970, p. 76.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 327.

- 1 2 Sellick 1981, p. 7.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, pp. 66–67, 76–77.

- ↑ Leleux, Sydney A. "West Somerset Mineral Railway". The Industrial Railway Record. Industrial Railway Society. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ Scott-Morgan 1980, p. 13.

- ↑ Madge (1975), pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Dale 2001, p. 36.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 340–2.

- ↑ "West Somerset Mineral Railway Action". Western Daily Press. British Newspaper Archive. 23 May 1919. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. 83.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 352–3.

- 1 2 Hopwood 1921, p. 156.

- ↑ "West Somerset Mineral Railway". Western Daily Press. British Newspaper Archive. 19 April 1923. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 357.

- ↑ "Neilson Box locos". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project.

- ↑ "Dreadful Collision on the West Somerset Mineral Railway". Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 26 August 1857. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hately 1977, p. 73.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, pp. 26–7.

- ↑ "Rowcliffe loco at Comberow". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, pp. 38–40.

- ↑ Scott-Morgan 1980, p. 12.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, p. 50.

- ↑ "Loco 370's history". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 57–58, 287 & 393.

- ↑ "Loco 391's history". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- 1 2 Jones 2011, p. 393.

- ↑ "Rowcliffe at Comberow". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- 1 2 Jones 2011, p. 394.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. 43.

- ↑ "Pontypool at Watchet". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 394–395.

- ↑ "Esperanza at Whitehall". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 Jones 2011, p. 395.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 287.

- ↑ "Whitfield in later days". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- ↑ "Newport in 1896". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 290.

- ↑ "ex-Metropolitan 4-4-0 on the line". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- 1 2 Jones 2011, p. 396.

- ↑ "Loco 212 on ATC trials". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- 1 2 Jones 2011, pp. 340–342 & 396.

- ↑ "Loco 213 on ATC trials". West Somerset Mineral Railway Project. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, p. 20.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, p. 29.

- ↑ Sellick 1970, pp. 36 & 78.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 340.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 344.

- ↑ Watchet WSMR locoshed at: 51°10′51″N 3°20′04″W / 51.1808°N 3.3345°W

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 278–9.

- ↑ Brendon Hill's first locoshed at: 51°05′56″N 3°23′33″W / 51.0990°N 3.3926°W

- ↑ Jones 2011, pp. 249–250.

- ↑ Brendon Hill's second locoshed at: 51°05′55″N 3°23′59″W / 51.0987°N 3.3996°W

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 247.

- ↑ Griffiths & Smith 1999, pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, Page 48 lower.

- 1 2 Jones 2011, pp. 317–9 & 396.

- ↑ Sellick 1981, Page 48 upper.

- ↑ "Images of sister loco Diana at Bala". google.

- 1 2 Kidner 1947, p. 20.

- ↑ Holland 2015, p. 30.

- ↑ The Railway Magazine 1940, pp. 659–660.

- ↑ The Railway Magazine 1941, p. 230.

- ↑ "WSMR and WSR side-by-side on overlain maps". National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016.

- ↑ "Discovering the Old Mineral Line, Brendon Hills, Exmoor". Exmoor for all. 8 April 2013. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ↑ Historic England. "Former Brendon Hill Mineral Railway Station (1057540)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ "Brendon Hill Chapel (formerly Beulah Bible Christian Chapel), Watchet". Methodist Heritage. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ↑ "The West Somerset Mineral Railway Project". Exmoor National Park. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ "West Somerset mineral line railway". funicular railways of the UK. Archived from the original on 3 October 2006. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- ↑ "West Somerset Mineral Railway". The Historical Association. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ "West Somerset Mineral Railway". Exmoor National Park. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ Historic England. "Carnarvon New Pit iron mine and section of mineral railway trackbed, 300 m south west of Heather House (1021352)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ↑ "Carnarvon New Pit iron mine and section of mineral railway trackbed, 300 metres south west of Heather House, Brompton Regis, West Somerset — Exmoor (NP)". Heritage at Risk. English Heritage. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

Sources

- Bodman, Martin (2012). Inclined Planes in the South West. Truro: Twelveheads Press. ISBN 978-0-906294-75-8.

- Bradshaw, George (2011) [December 1895]. Bradshaw's Rail Times for Great Britain and Ireland December 1895: A Reprint of the Classic Timetable Complete with Period Advertisements and Shipping Connections to All Parts. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-1-908174-11-6. OCLC 832579861.

- Butt, R. V. J. (October 1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199. OL 11956311M.

- Carter, E. (1959). An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles. London: Cassell. ASIN B000WSRHU6. OCLC 52023502.

- Dale, Peter (2001). Somerset's Lost Railways. Catrine: Stenlake Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84033-171-4.

- Farr, Grahame (1954). Somerset Harbours, including the Port of Bristol. London: Christopher Johnson. ASIN B0000CIU0I. OCLC 317800687.

- Griffiths, Roger; Smith, Paul (1999). The Directory of British Engine Sheds and Principal Locomotive Servicing Points: 1 Southern England, the Midlands, East Anglia and Wales. OPC Railprint. ISBN 978-0-86093-542-1. OCLC 59458015.

- Hately, Roger (1977). Industrial locomotives of South Western England. Greenford: Industrial Railway Society Publications. ISBN 978-0-901096-23-4.

- Holland, Julian (2015). Exploring Britain's Lost Railways. Glasgow: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-794901-4.

- Hopwood, H.L. (September 1921). "The West Somerset Mineral Railway". The Railway Magazine. London: Tothill Press Limited. ISSN 0033-8923.

- Jones, Michael H. (2011). The Brendon Hills Iron Mines and the West Somerset Mineral Railway. Lydney: Lightmoor Press. ISBN 978-1-899889-53-2. OCLC 795179029.

- Jowett, Alan (March 1989). Jowett's Railway Atlas of Great Britain and Ireland: From Pre-Grouping to the Present Day (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-086-0. OCLC 22311137.

- Kidner, R W (1947) [1937]. Standard Gauge Light Railways (2nd ed.). Chislehurst: Oakwood Press. OCLC 642410845.

- "The West Somerset Mineral Railway". Notes and News. The Railway Magazine. Vol. 86. London: Tothill Press Limited. December 1940. pp. 659–660. ISSN 0033-8923.

- "West Somerset Mineral Remains". Notes and News. The Railway Magazine. Vol. 87. London: Tothill Press Limited. May 1941. p. 230. ISSN 0033-8923.

- Madge, Robin (1975) [1971]. "7: Watchet–Brendon Hill". Railways Round Exmoor. Dulverton: Exmoor Press. ISBN 978-0-900131-18-9.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1990). Branch Line to Minehead: Preservation Perfection. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-0-906520-80-2.

- Oakley, Mike (2002). Somerset Railway Stations. Wimborne Minster: Dovecote Press. ISBN 978-1-904349-09-9.

- Quick, Michael (2009) [2001]. Railway passenger stations in Great Britain: a chronology (4th ed.). Oxford: Railway & Canal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-901461-57-5. OCLC 612226077.

- Scott-Morgan, John (1980). British Independent Light Railways. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-7933-2.

- Sellick, Roger J. (1981) [1976]. The Old Mineral Line (2nd ed.). Dulverton: The Exmoor Press. ISBN 978-1-84114-692-8.

- Sellick, Roger J. (1970) [1962]. The West Somerset Mineral Railway and the story of the Brendon Hills Iron Mines (2nd ed.). Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-4961-8.

- Sellick, R J; Spark, Stephen (Summer 1987). "Comberow Incline". British Railway Journal. No. 17. Didcot: Wild Swan Publications Ltd. ISSN 0265-4105.

- Thomas, David St John (1966). Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: The West Country v. 1. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-946537-17-4.

Further reading

- Carpenter, Roger (Winter 1988). Karau, Paul; Beale, Gerry (eds.). "Comberow Incline — West Somerset Mineral Railway". British Railway Journal. Didcot: Wild Swan Publications Ltd (20). ISSN 0265-4105.

- Gathercole, Clare (2003) Watchet Archaeological Assessment (Somerset County council)

- Leleux, S.A. (1969) West Somerset Mineral Railway, Industrial Railway Record

- Maggs, Colin (2013). The Branch Lines of Somerset. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-0226-7.

- Moore, F. (July 1914). "The West Somerset Mineral Railway". Locomotive Magazine. London: Locomotive Publishing Company. 20 (264): 196–8.

- Smith, Martin (1995). An illustrated history of Exmoor's railways. Caernarfon: Irwell Press. ISBN 978-1-871608-66-3.

- Yorke, Stan (2007). Lost Railways of Somerset. Lost Railways. Newbury, Berkshire: Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-84674-057-2.

- Ordnance Survey Map: Explorer OL9 Exmoor (The top of the incline is at Grid Reference ST023344)

External links

- "A walk on the West Somerset Mineral Railway". Friends of the West Somerset Railway. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "An Outline History of the West Somerset Mineral Railway". West Country Railway Archives. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008.

- "Ordnance Survey 6 inch map of Watchet, 1902". National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016.

- "Ordnance Survey 25 inch map of Brendon Hill in 1887". National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017.

- "Line and features overlain on OS maps". Rail Map Online. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- "The line and its stations". Disused Stations. Archived from the original on 24 May 2016.

- "West Somerset Mineral line inclines". Dr. Mark Hows. Archived from the original on 3 October 2006.

- "West Somerset Mineral Railway". Exmoor National Park. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016.

- "West Somerset Mineral Railway". Transport Trust. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016.

- "West Somerset Mineral Railway". John Speller. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016.

- "West Somerset Mineral Line Association". The Association itself. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016.

- "West Somerset Mineral Railway Project". Exmoor National Park. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016.

- "West Somerset Mineral Railway Project". The Project itself. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009.