The Western Cape Water Supply System (WCWSS) is a complex water supply system in the Western Cape region of South Africa, comprising an inter-linked system of six main dams, pipelines, tunnels and distribution networks, and a number of minor dams, some owned and operated by the Department of Water and Sanitation and some by the City of Cape Town.[1]

Components

The largest component of the WCWSS is the Riviersonderend-Berg River Government Water Scheme, which is a large inter-basin water transfer scheme that regulates the flow of the Sonderend River flowing South towards the Indian Ocean, the Berg River flowing North towards the Atlantic Ocean and Eerste River that flows into False Bay.

The principal dams are all located in the Cape Fold Mountains to the east of Cape Town. They are:

- Theewaterskloof Dam

- Wemmershoek Dam

- Steenbras Lower Dam

- Steenbras Upper Dam

- Voëlvlei Dam

- Berg River Dam

These six major dams provide 99.6% of the combined storage capacity, and 8 minor dams the remaining 0.4%. The levels of these dams are recorded and published in weekly reports by the Department of Water and Sanitation.[2][3][4]

The largest dam in the system is the Theewaterskloof Dam on the Sonderend River, with a storage capacity of 480 million cubic meters, or 41% of the total storage. It is linked to the Cape Town water system through the Faure treatment works via the Kleinplass balancing dam with a tunnel system through the Hottentots Holland Mountains. The Berg River dam (130 million cubic meter) was added to this system in 2009.

Other storage dams of the WCWSS are the Voëlvlei Dam (159 million cubic meters), the Wemmershoek Dam (59 million cubic meter) in the Berg River basin, the Upper and Lower Steenbras Dams on the Steenbras River as well as the Palmiet Pumped Storage Scheme dams on the Palmiet River, from which water can be transferred to the Steenbras dams.[5]

In 2009 storage capacity in the system was increased by 17% from 768 to 898 million cubic metres through the completion of the Berg River Dam.[6]

| Major Dams | Capacity

(thousand cubic metres) |

Location | Minor Dams | Capacity (thousand cubic

metres) |

Location | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Theewaterskloof (Villiersdorp) | 480188 |  |

G | Kleinplaats (Simon's Town) | 1368 |  |

| B | Voëlvlei (Gouda) | 164095 |  |

H | Woodhead (Table Mountain) | 954 |  |

| C | Berg River (Franschhoek) | 130010 |  |

I | Hely-Hutchinson (Table Mountain) | 925 |  |

| D | Wemmershoek (Franschhoek) | 58644 |  |

J | Land-en-Zeezicht (Helderberg) | 451 |  |

| E | Steenbras Lower (Grabouw) | 33 517 |  |

K | De Villiers (Table Mountain) | 243 |  |

| F | Steenbras Upper (Grabouw) | 31767 | L | Lewis Gay (Simon's Town) | 182 |  | |

| M | Victoria (Table Mountain) | 128 |  | ||||

| N | Alexandra (Table Mountain) | 126 |

Water use

In 2009, 63% of the water in the system was being used for domestic and industrial purposes in the city of Cape Town, which has a population of over 4 million. Smaller towns used 5%, and 32% was used by agriculture.[5] Within the city, in 2016/2017, 64.5% of water went to houses, flats and complexes, while 3.6% went to informal settlements.[7]

The system provides water to irrigate about 15,000ha of farmland, where high-value fruit and vegetables are grown. From the early 1970s until the mid-2000s water consumption in Cape Town increased by about 300%, increasing the competition for water with irrigated agriculture. This has been exacerbated by several unusually dry years, such as in 1994-1995 when storage in the system was only one third of average storage. Farmers have adapted by significantly improving irrigation efficiency and shifting even more land into the production of high-value crops.[8]

The system also generates pumped storage hydropower using an installed capacity of 400 Megawatt (MW) on the Palmiet River and 180MW on the Steenbras River.

Water crisis 2015-present

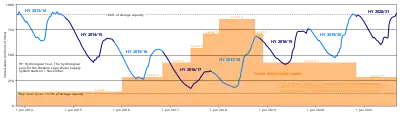

The Cape Town water crisis in South Africa was a period of severe water shortage in the Western Cape region, most notably affecting the City of Cape Town. While dam water levels had been decreasing since 2015, the Cape Town water crisis peaked during mid-2017 to mid-2018 when water levels hovered between 14 and 29 percent of total dam capacity.

In late 2017, there were first mentions of plans for "Day Zero", a shorthand reference for the day when the water level of the major dams supplying the City could fall below 13.5 percent.[9][10][11] "Day Zero" would mark the start of Level 7 water restrictions, when municipal water supplies would be largely switched off and it was envisioned that residents could have to queue for their daily ration of water. If this had occurred, it would have made the City of Cape Town the first major city in the world to run out of water.[12][13] The water crisis occurred at the same time as the Eastern Cape drought, located in a separate region nearby.

The City of Cape Town implemented significant water restrictions in a bid to curb water usage, and succeeded in reducing its daily water usage by more than half to around 500 million litres (130,000,000 US gal) per day in March 2018.[14] The fall in water usage led the City to postpone its estimate for "Day Zero", and strong rains starting in June 2018 led to dam levels recovering.[15] In September 2018, with dam levels close to 70 percent, the city began easing water restrictions, indicating that the worst of the water crisis was over.[16] Good rains in 2020 effectively broke the drought and resulting water shortage when dam levels reached 95 percent.[17]See also

References

- ↑ Address by Mr Ronnie Kasrils, MP, minister of Water Affairs and Forestry, at the Berg Water Project signing ceremony on 15 April 2003, in Cape Town, accessed on 11 December 2009

- ↑ "This Week's Dam levels". www.capetown.gov.za. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- ↑ "Western Cape Dam Levels". www.elsenburg.com. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- ↑ "Department of Water and Sanitation - Surface Water Storage". niwis.dws.gov.za. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- 1 2 Department of Water Affairs and Forestry:Western Cape Water Reconciliation Strategy, Newsletter 5, March 2009, accessed on 11 December 2009

- ↑ City of Cape Town:Cape Town's water supply boosted, 17 March 2009, accessed on 12 December 2009

- ↑ Makou, Gopolang (21 August 2017). "Do Formal Residents Use 65% of Cape Town's Water?". Africa Check.

- ↑ John M. Callaway, Daniel B. Louw and Molly Hellmuth:Benefits and Costs of Measures for Coping with Water and Climate Change:Berg River Basin, South Africa, in: Fulco Ludwig, Pavel Kabat, Henk van Schaik and Michael van der Valk: Climate change adaptation in the water sector, London 2009, p. 205-226

- ↑ Cassim, Zaheer (19 January 2018). "Cape Town could be the first major city in the world to run out of water". USA Today.

- ↑ Poplak, Richard (15 February 2018). "What's Actually Behind Cape Town's Water Crisis". The Atlantic. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ↑ York, Geoffrey (8 March 2018). "Cape Town residents become 'guinea pigs for the world' with water-conservation campaign". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ "Day Zero, when is it, what is it and how can we avoid it". City of Cape Town.

- ↑ Booysen, Marthinus Johannes; Visser, Martine; Burger, Ronelle (2019-01-05). Temporal case study of household behavioural response to Cape Town's Day Zero using smart meter data (Report). engrXiv. doi:10.31224/osf.io/6nckp. PMID 30472543.

- ↑ Narrandes, Nidha (14 March 2018). "Cape Town water usage lower than ever". Cape Town etc.

- ↑ Myburgh, Janine (29 June 2018). "Chamber delighted by Day-Zero's death". Cape Messenger. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ Pitt, Christina (10 September 2018). "City of Cape Town relaxes water restrictions, tariffs to Level 5". News24. Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "After the drought: Cape Town's gushing water". GroundUp News. 2020-09-07. Retrieved 2020-09-11.