Wheelchair sport classification is a system designed to allow fair competition between people of different disabilities, and minimize the impact of a person's specific disability on the outcome of a competition. Wheelchair sports is associated with spinal cord injuries, and includes a number of different types of disabilities including paraplegia, quadriplegia, muscular dystrophy, post-polio syndrome and spina bifida. The disability must meet minimal body function impairment requirements.[footnotes 1] Wheelchair sport and sport for people with spinal cord injuries is often based on the location of lesions on the spinal cord and their association with physical disability and functionality.

Classification for spinal cord injuries and wheelchair sport is overseen by International Wheelchair and Amputee Sports Federation (IWAS). Classification for spinal cord injuries internationally is also handled on a sport specific basis, with the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) being the classifier for a number of sports including alpine skiing, biathlon, cross country skiing, ice sledge hockey, powerlifting, shooting, swimming, and wheelchair dance. Classification is also handled nationally by national wheelchair sport organizations, or sport specific organizations.

Wheelchair sport classification was first experimented with by Ludwig Guttmann at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital during the 1940s, and was formalized in the 1950s. This was a medical based classification system. It was the used International Stoke Mandeville Wheelchair Sports Federation (ISMWSF) at their founding in 1960, when the first International Stoke Mandeville Games were held in Rome. The 1960s, 1970s and 1980s would see a debate about the merits of the medical based system. Changes towards a functional classification system started in some sports in the late 1970s and 1980s before going wider in the early 1990s. Major changes took place in the 1990s, which facilitated the ability for people with spinal cord injuries to compete with people with different types of disabilities. These trends continued into the 2000s.

Traditionally, the classes used for IWAS have been based on track and field with these being applied for other sports. There are four classes for track and eight for track and field. These classes are known as F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, F6, F7 and F8. They are comparable to sport specific classes used by other classifying bodies. The process for classification has a medical and functional classification process. This process is often sport specific.

Purpose

The purpose of classification in wheelchair sports is to allow fair competition between people with different types of disabilities.[1] It is to minimize the importance of the type of impairment a person has on the outcome of a competition.[2] Classification based on disabilities is at times comparable to classification systems used in other sports based on weight, age and gender in regards to its purpose as these potentially impact results.[3]

Some wheelchair sports state variants of this in sport specific ways.[2][4][5] In wheelchair fencing, the purpose of classification is to insure that fencers are classified based on equitable functional mobility so that their training, skill level, talent and experience determine the outcome of a match, not their disability type. This insures fairness in the sport.[4] In wheelchair rugby, the purpose of classification is to give structure to the sport by minimizing the impact of different levels of functional disabilities on the court as it pertains to the outcome of the game.[5]

Sports people with spinal cord injuries are generally eligible to participate in include archery, boccia, cycling, equestrian, paracanoe, paratriathlon, powerlifting, rowing, sailing, shooting, swimming, table tennis, track and field, wheelchair basketball, wheelchair fencing, wheelchair rugby and wheelchair tennis.[6]

Disabilities and physiology

Wheelchair sport classification includes a number of disabilities that cause problems with the spinal cord. These include paraplegia, quadriplegia, muscular dystrophy, post-polio syndrome and spina bifida.[6][footnotes 1] Minimal qualification for wheelchair sport is minimal body function impairment. In practice, ISMWSF has defined this as 70 points or less on the muscle group function test for people with lower limb and trunk impairments. They have no minimum disability for upper limb impairments.[7]

The location of lesions on different vertebrae tend to be associated with disability levels and functionality issues. C5 is associated with elbow flexors. C6 is associated with wrist flexors. C7 is associated with elbow flexors. C8 is associated with finger flexors. T1 is associated with finger abductors. T6 is associated with abdominal innervation beginning. T12 and L1 are associated with abdominal innervation complete. L2 is associated with hip flexors. L3 is associated with knee extensors. L4 is associated with ankle doris flexors. L5 is associated with long toe extensors. S1 is associated with ankle plantar flexors.[8] The location of these lesions and their association with physical disability is used with a number of medical and functional classification systems for wheelchair sports.[4][7][8][9][10][11][12][13]

Governance

In general, classification for spinal cord injuries and wheelchair sport is overseen by International Wheelchair and Amputee Sports Federation (IWAS),[14][15] having taken over this role following the 2005 merger of ISMWSF and ISOD.[16][17] From the 1950s to the early 2000s, wheelchair sport classification was handled International Stoke Mandeville Games Federation (ISMGF).[16][18][19]

Some sports have classification managed by other organizations. In the case of athletics, classification is handled by IPC Athletics.[20] Wheelchair rugby classification has been managed by the International Wheelchair Rugby Federation since 2010.[21] Lawn bowls is handled by International Bowls for the Disabled.[22] Wheelchair fencing is governed by IWAS Wheelchair Fencing (IWF).[23] The International Paralympic Committee manages classification for a number of spinal cord injury and wheelchair sports including alpine skiing, biathlon, cross country skiing, ice sledge hockey, powerlifting, shooting, swimming, and wheelchair dance.[15] When the International Paralympic Committee evaluates an athlete and determines their classification, they ask the following three questions:[24]

1. Does the athlete have an eligible impairment for this sport?

2. Does the athlete's eligible impairment meet the minimum disability criteria of the sport?

3. Which sport class describes the athlete's activity limitation most accurately?

Some sports specifically for people with disabilities, like race running, have two governing bodies that work together to allow different types of disabilities to participate. Race running is governed by both the CPISRA and IWAS, with IWAS handling sportspeople with spinal cord related disabilities.[25]

Classification is also handled at the national level or at the national sport specific level. In the United States, this has been handled by Wheelchair Sports, USA (WSUSA) who managed wheelchair track, field, slalom, and long-distance events.[26] For wheelchair basketball in Canada, classification is handled by Wheelchair Basketball Canada.[27]

History

Ludwig Guttmann at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital began experimenting with spinal cord injury sport classification systems during the 1940s using a medical based system.[18] His classification system was formally formalized in 1952 at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital. This system was published in the Handbook of Rules, which was distributed to people involved with paraplegic sport at the time including coaches, doctors and physiotherapists in various countries. At the time, this classification system was a medical classification.[19] The classification system has historically been based around the one used for athletics.[16][26] Guttmann was subsequently adopted by the International Stoke Mandeville Wheelchair Sports Federation (ISMWSF) at their founding in 1960, when the first International Stoke Mandeville Games were held in Rome, Italy that year.[16][26][28] During that first decade following the first Games, people oftentimes tried to cheat classification to get in classified more favorably. The group most likely to try to cheat at classification were wheelchair basketball players with complete spinal cord injuries located at the high thoracic transection of the spine.[28][29] Classification in this decade and in the 1970s, involved being examined in a supine position on an examination table, where multiple medical classifiers would often stand around the player, poke and prod their muscles with their hands and with pins. The system had no built in privacy safeguards and players being classified were not insured privacy during medical classification nor with their medical records.[29]

Wheelchair basketball classification was underway during the 1960s. The original wheelchair basketball classification system designed in 1966 had 5 classes: A, B, C, D, S. Each class was worth so many points. A was worth 1, B and C were worth 2. D and S were worth 3 points. A team could have a maximum of 12 points on the floor. This system was the one in place for the 1968 Summer Paralympics. Class A was for T1-T9 complete. Class B was for T1-T9 incomplete. Class C was for T10-L2 complete. Class D was for T10-L2 incomplete. Class S was for Cauda equina paralysis.[29] From 1969 to 1973, a classification system designed by Australian Dr. Bedwell was used in wheelchair basketball. This system used some muscle testing to determine which class incomplete paraplegics should be classified in. It used a point system based on the ISMGF classification system. Class IA, IB and IC were worth 1 point. Class II for people with lesions between T1-T5 and no balance were also worth 1 point. Class III for people with lesions at T6-T10 and have fair balance were worth 1 point. Class IV was for people with lesions at T11-L3 and good trunk muscles. They were worth 2 points. Class V was for people with lesions at L4 to L5 with good leg muscles. Class IV was for people with lesions at S1-S4 with good leg muscles. Class V and IV were worth 3 points. The Daniels/Worthington muscle test was used to determine who was in class V and who was class IV. Paraplegics with 61 to 80 points on this scale were not eligible. A team could have a maximum of 11 points on the floor. The system was designed to keep out people with less severe spinal cord injuries, and had no medical basis in many cases.[29]

During the 1960s and 1970s, ISMGF classification cheating occurred in both swimming and wheelchair basketball. Some of the medical classifications for many sportspeople appeared arbitrary, with people of different functional levels being put into the same class. This made the results for many games and swimming races appear to be completely arbitrary. Impacted sportspeople were starting to demand that changes be made to address this. The German men and women's national wheelchair basketball teams were leading the charge in this regard, offering to test out and actually testing new systems that were being developed by Cologne-based Horst Strokhkendl. This process started in 1974 with a final report being written in 1978. Despite the report being submitted to ISMGF, no changes were made for years.[29]

It was during the 1970s, against this backdrop of frustration with the classification system and issues of classification cheating that a debate began to take place in the physical disability sport community about the merits of a medical versus functional classification system. During this period, people had strong feelings both ways but few practical changes were made to existing classification systems.[29]

Big changes to classification that differed from the system created in the 1950s really began to take place in the 1980s with a move away from medical classification to functional classification.[19][29] ISMWSF was one of the organizations driving this change on the wheelchair sport side.[19][29] In 1982, wheelchair basketball finally made the move to a functional classification system internationally. While the traditional medical system of where a spinal cord injury was located could be part of classification, it was only one advisory component. A maximum of 14 points was allowed on the floor at any time. Medical exams were removed except with player consent. Classification took place on the court, with classifiers observing players in action. All players were advised of this new system when it was implemented to minimize confusion. A special wheelchair basketball classification subcommittee was also set up inside ISMGF to manage wheelchair basketball classification.[29] Wheelchair fencing's classification system was another one making the move to a functional system, with the IWF Classification system being implemented for the 1988 Summer Paralympics in Seoul. It had first been used at the European Championships in Glasgow 1987, and was small changes were made to this system before its use at the 1988 Games.[4] Para-equestrian was also starting this process, having a combined class for spinal cord injuries and Les Autres at the 1984 Summer Paralympics, with the competition being held in Texas. There were 16 total competitors, with three having spinal cord injuries, two having multiple scelorsis, two with other neurological impairments, and nine others.[30]

Changes to classification continued on in earnest in the 1990s.[5][21][29] In 1991, the International Functional Classification Symposium was held concurrently with the 1991 International Stoke Mandeville Games. Changes were made to the classification system that were formally implemented for the 1992 Summer Paralympics in Barcelona. This system was a more refined form of the original system developed by Guttmann during the 1950s.[19] Wheelchair rugby was one of the sports to make the transition in 1991 from a medical based classification system to a functional one. Spinal cord injury medical assessment was used in that transition period as part of the process of making a functional classification assessment.[5]

In 1992, IWAS started governing wheelchair rugby classification after the sport was created in Canada in 1977. The sport made the switch to a functional classification system in 1991 as part of an effort to be inclusive of people with a broader range of disabilities beyond spinal cord injuries. The change to a functional system allowed people with polio, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis and amputations to fully participate in the sport.[21][31][32] In October 1996, the first edition of wheelchair rugby's new classification rules went into effect.[5] In November 1999, the second edition of wheelchair rugby's classification rules went into effect.[5]

A 1996 study of American attitudes of different disability groups participating in sport by other disability sportspeople found amputees were viewed most favorably, followed by les autres, paraplegia and quadriplegia, and visual impairment. Sportspeople with cerebral palsy were viewed the least favorably.[33]

International wheelchair sport governance for classification was taken over by IWAS following the 2005 merger of ISMWSF and ISOD.[16][17] Changes to classification and classification continued on during the rest of the 2000s. In 2008, a number of small changes were made to wheelchair rugby's classification rules in accordance with IPC guidelines following a multi year review. This culminated in the third edition of wheelchair rugby classification.[5] In 2010, the International Wheelchair Rugby Federation formally separated from IWAS and took over management of classification of their sport themselves.[21] In 2010, the IPC announced that they would release a new IPC Athletics Classification handbook that specifically dealt with physical impairments. This classification guide would be put into effect following the closing ceremony of the 2012 Summer Paralympics.[34]

Collaborations and efforts to allow different types of disabilities to compete against each other expanded during the 2010s. In 2011, IWAS and CPISRA signed a memorandum of understanding that allowed people with spinal cord injuries to compete in CPISRA race running events.[25] In June 2011, a revised version of the third edition of wheelchair rugby classification rules went into effect.[5] In January 2015, a revised version of the third edition of wheelchair rugby classification rules went into effect.[5]

Classes

Traditionally, the classes used for IWAS have been based on track and field with these being applied for other sports. There are four classes for track and eight for track and field. Variants of these classes based on spinal cord dysfunction are used in other sports.[7] These classes date back to the earliest days of wheelchair sport, when the classification system was 1A, 1B, 1C, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. There has been some modification since then in terms of functional definitions though medical definitions of location of the location of a lesion on the spinal cord have remained relatively similar.[16][18][19][29]

| Class | Historical name | Neurological level | Athletics | Cycling | Swimming | Other sports | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1/T1/SP1 | 1A Complete | C6 | F51 | H1 | S1, S2 | Archery: ARW1

Electric wheelchair hockey: Open Wheelchair fencing: 1A/Category C |

[4][7][9][10][11][12][13][35] |

| F2/T2/SP2 | 1B Complete, 1A Incomplete | C7 | F52 | H2 | S1, S2, SB3, S4 | Archery: ARW1

Electric wheelchair hockey: Open Ten pin bowling: TPB8 Wheelchair fencing: 1B/Category C |

[4][7][9][10][11][12][13][16][35][36] |

| F3/T3/SP3 | 1C Complete, 1B Incomplete | C8 | F52, F53 | H3 | S3, SB3, S4, S5 | Archery: ARW1, ARW2

Electric wheelchair hockey: Open Rowing: AS Table tennis: Grade 3, Grade 4, Grade 5 Wheelchair fencing: 1B/Category C |

[4][7][9][10][11][12][13][16][35][36][37] |

| F4/T4/SP4 | 1C Incomplete, 2, Upper 3 | T1 - T7 | F54 | H4, H5 | S3, SB3, SB4, S5 | Archery: ARW2

Rowing: AS Wheelchair basketball: 1 point player Wheelchair fencing: 2/Category B |

[4][7][9][10][11][16][35][36][38][39] |

| F5/SP5 | Lower 3, Upper 4 | T8 - L1 | F55 | SB3, S4, SB4, S5, SB5, S6 | Archery: ARW2

Rowing: TA Wheelchair basketball: 2 point player Wheelchair fencing: 2, 3/Category B, A |

[4][7][9][10][11][16][36][38][39] | |

| F6/SP6 | Lower 4, Upper 5 | L2 - L5 | F56 | S5, SB5, S7, S8 | Wheelchair basketball: 3 point player, 4 point player

Wheelchair fencing: 3, 4/Category A |

[4][7][9][10][11][16][36][38][39] | |

| F7/SP7 | Lower 5, 6 | S1 - S2 | F57 | S5, S6, S10 | Rowing: LTA

Wheelchair basketball: 4 point player Wheelchair fencing: 4/Category B |

[4][7][9][10][11][38][39] | |

| F8/SP8 | F42, F43, F44, F58 | S8, S9, S10 | [7][9][10][11] | ||||

| F9 | Standing F8 | F42, F43, F44 | [9][10][40][41][42][43] |

In athletics, the classes in the T50s and F50s generally correspond to wheelchair sport classes. SP8 and SP9 athletes may be found in F40s and T40s classes.[9] Swimming classes for people with spinal cord injuries conform less to wheelchair sport classes. SP1 and SP2 swimmers can compete in S1. SP3 swimmers can compete in S3. SP4 swimmers may be found in S3 and S5. SP5 swimmers may be classified as S4 or S5. SP6 swimmers can be found in S5. SP7 swimmers may be in S5 or S6. SP8 swimmers may be found in S8.[11] In cycling, SP1 sportspeople compete in the H1 class.[44] In archery, people with spinal cord injuries can be found in ARW1, ARW2 or ARST based on the severity of their disability.[35] People with spinal cord injuries are often found in the handcycling classes of H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5 for cycling.[45][46][47]

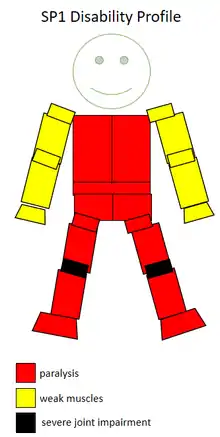

Profile of an F1 sportsperson

Profile of an F1 sportsperson Profile of an F2 sportsperson

Profile of an F2 sportsperson Profile of an F3 sportsperson

Profile of an F3 sportsperson Profile of an F4 sportsperson

Profile of an F4 sportsperson Profile of an F5 sportsperson

Profile of an F5 sportsperson Profile of an F6 sportsperson

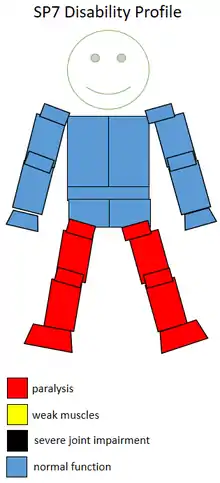

Profile of an F6 sportsperson Profile of an F7 sportsperson

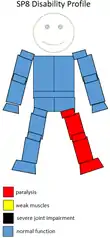

Profile of an F7 sportsperson Profile of an F8 sportsperson

Profile of an F8 sportsperson Athletics specific classification for wheelchair sport athletes showing T51, T52, T53 and T54 spinal injury locations.

Athletics specific classification for wheelchair sport athletes showing T51, T52, T53 and T54 spinal injury locations. Cycling classification for spinal cord injuries for H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5

Cycling classification for spinal cord injuries for H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5 Functional profile of a wheelchair sportsperson in the F8 class.

Functional profile of a wheelchair sportsperson in the F8 class.

Getting classified

Classification is often sport specific.[23][48][49]

Medical classification for wheelchair sport can consist of medical records being sent to medical classifiers at the international sports federation. The sportsperson's physician may be asked to provide extensive medical information including medical diagnosis and any loss of function related to their condition. This includes if the condition is progressive or stable, if it is an acquired or congenital condition. It may include a request for information on any future anticipated medical care. It may also include a request for any medications the person is taking. Documentation that may be required my include x-rays, ASIA scale results, or Modified Ashworth Scale scores.[50]

One of the standard means of assessing functional classification is the bench test, which is used in swimming, lawn bowls and wheelchair fencing.[23][48][49] Using the Adapted Research Council (MRC) measurements, muscle strength is tested using the bench press for a variety of spinal cord related injuries with a muscle being assessed on a scale of 0 to 5. A 0 is for no muscle contraction. A 1 is for a flicker or trace of contraction in a muscle. A 2 is for active movement in a muscle with gravity eliminated. A 3 is for movement against gravity. A 4 is for active movement against gravity with some resistance. A 5 is for normal muscle movement.[49]

Wheelchair fencing classification has 6 test for functionality during classification, along with a bench test. Each test gives 0 to 3 points. A 0 is for no function. A 1 is for minimum movement. A 2 is for fair movement but weak execution. A 3 is for normal execution. The first test is an extension of the dorsal musculature. The second test is for lateral balance of the upper limbs. The third test measures trunk extension of the lumbar muscles. The fourth test measures lateral balance while holding a weapon. The fifth test measures the trunk movement in a position between that recorded in tests one and three, and tests two and four. The sixth test measures the trunk extension involving the lumbar and dorsal muscles while leaning forward at a 45 degree angle. In addition, a bench test is required to be performed.[23]

Electric wheelchair hockey classification has a three part process. The first is the submission of written medical information. The second is determining the edibility of classification based on minimal disabilities. In the case of electric wheelchair hockey, it is a T1 level spinal injury or above, having cerebral palsy, having a neuromuscular disease, having an orthopedic disabilities excluding OI, having brittle bone disease, or having severe kyphoscoliosis with poor sitting balance. After this, functional classification takes place using three tests, including cone navigation, hitting and slalom.[12]

Criticisms

One of the criticisms of the wheelchair sport classification system is that it results in sportspeople in this class being the most celebrated on the Paralympic level, and held up as exemplars of people with disabilities. Those with greater levels of impairment are given much less attention, have fewer sporting opportunities, and are often segregated off into sports that are not fully integrated with able bodied sport.[17]

Notes

- 1 2 Some wheelchair sports are open to people with disabilities other than spinal cord injuries. These include Impaired muscle power, Athetosis, impaired passive range of movement, Hypertonia, limb deficiency, Ataxia and leg length difference. Many of these are covered by Les Autres sports classification, Cerebral Palsy sports classification and amputee sport classification. These are discussed on those specific pages or on sport specific classification articles.

References

- ↑ "INTRODUCTION to CLASSIFICATION IN SPORT". International Bowls for the Disabled. International Bowls for the Disabled. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- 1 2 Tweedy, S. M.; Vanlandewijck, Y. C. (2011-04-01). "International Paralympic Committee position stand—background and scientific principles of classification in Paralympic sport". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 45 (4): 259–269. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2009.065060. ISSN 1473-0480. PMID 19850575. S2CID 2123112.

- ↑ "IPC Classification - Paralympic Categories & Classifications". International Paralympic Committee. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 IWAS (20 March 2011). "IWF RULES FOR COMPETITION, BOOK 4 – CLASSIFICATION RULES" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "IWRF Classification Manual 3rd Edition rev-2015" (PDF). IWRF. IWRF. 2015.

- 1 2 "Les Autres: Paralympic Classification Interactive". Team USA. US Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Tweedy, S. M. (2003). The ICF and Classification in Disability Athletics. In R. Madden, S. Bricknell, C. Sykes and L. York (Ed.), ICF Australian User Guide, Version 1.0, Disability Series (pp. 82-88)Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- 1 2 International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 National Governing Body for Athletics of Wheelchair Sports, USA. Chapter 2: Competition Rules for Athletics. United States: Wheelchair Sports, USA. 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 IWAS Committee Electric Wheelchair Hockey (ICEWH) (July 2014). "REPORT CLASSIFICATION PROCESS" (PDF). IWAS Committee Electric Wheelchair Hockey (ICEWH). IWAS. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "UCI Cycling Regulations - Para cycling" (PDF). Union Cycliste International website. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "About IWAS". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Retrieved 2016-07-30.

- 1 2 "Other Sports". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Retrieved 2016-07-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 KOCCA (2011). "장애인e스포츠 활성화를 위한 스포츠 등급분류 연구" [Activate e-sports for people with disabilities: Sports Classification Study] (PDF). KOCCA (in Korean).

- 1 2 3 Andrews, David L.; Carrington, Ben (2013-06-21). A Companion to Sport. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118325285.

- 1 2 3 Chapter 4. 4 - Position Statement on background and scientific rationale for classification in Paralympic sport (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. December 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "ISMWSF History". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Retrieved 2016-07-29.

- ↑ "IWAS Athletics - Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation". IWASF. IWASF. Retrieved 2016-07-29.

- 1 2 3 4 "IWAS transfer governance of Wheelchair Rugby to IWRF". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- ↑ "Explanation of classification in para-sports". International Bowls for the Disabled. International Bowls for the Disabled. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 IWAS (20 March 2011). "IWF RULES FOR COMPETITION, BOOK 4 – CLASSIFICATION RULES" (PDF).

- ↑ "IPC Classification - Paralympic Categories & Classifications". International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 2020-02-27.

- 1 2 "New Records in CPISRA Race Running". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. 2011. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- 1 2 3 "SPECIAL SECTION ADAPTATIONS TO USA TRACK & FIELD RULES OF COMPETITION FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field. 2002.

- ↑ Canada, Wheelchair Basketball. "Classification". Wheelchair Basketball Canada. Wheelchair Basketball Canada. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- 1 2 "ISMWSF History". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Thiboutot, Armand; Craven, Philip. The 50th Anniversary of Wheelchair Basketball. Waxmann Verlag. ISBN 9783830954415.

- ↑ Thomas, Nigel (2002). "Sport and Disability" (PDF). pp. 105–124. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Paralympic Wheelchair Rugby - overview, rules and classification | British Paralympic Association". British Paralympic Association. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- ↑ Woude, Luc H. V.; Hoekstra, F.; Groot, S. De; Bijker, K. E.; Dekker, R. (2010-01-01). Rehabilitation: Mobility, Exercise, and Sports : 4th International State-of-the-Art Congress. IOS Press. ISBN 9781607500803.

- ↑ Mastro, James V. (1996). "Attitudes of Elite Athletes With Impairments Toward One Another: A Hierarchy of Preference" (PDF). Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. Human Kinetics Publishers, lnc. 13 (2): 97–210. doi:10.1123/apaq.13.2.197.

- ↑ "IPC Athletics Amendments". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. 2010. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gil, Ana Luisa (2013). Management of Paralympics Games: Problems and perspectives. Brno, Czech Republic: Faculty of Sport studies, Department of Social Sciences in Sport And Department of Health Promotion, MASARYK UNIVERSITY.

- 1 2 3 4 5 International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual.

- ↑ Chapter 4. 4 - Position Statement on background and scientific rationale for classification in Paralympic sport (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. December 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 "Applying for Adaptive Classification" (PDF). British Rowing. British Rowing.

- 1 2 3 4 "Simplified Rules of Wheelchair Basketball and a Brief Guide to the Classification system". Cardiff Celts. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ↑ "National Junior Disabled Sports Championships 2004 Registration Packet" (PDF). Mesa Association of Sports for the Disabled. Mesa Association of Sports for the Disabled. 2004.

- ↑ National Governing Body for Athletics of Wheelchair Sports, USA. Chapter 2: Competition Rules for Athletics. United States: Wheelchair Sports, USA. 2003.

- ↑ USA Track & Field (2007). "Special Section Adaptions to the USA Track & Field Rules of Competition for Individuals with Disabilities" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field.

- ↑ "OFFICIAL GUIDE & RULES OF GAMES 2006" (PDF). GAELIC ATHLETICS & CYCLE ASSOCIATION. GAELIC ATHLETICS & CYCLE ASSOCIATION. 2006.

- ↑ "UCI Cycling Regulations - Para cycling" (PDF). Union Cycliste International website. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Handcycling". Wheelchair Sports NSW. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

- ↑ Mitchell, Cassie. "About Paracycling". cassie s. mitchell, ph.d. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

- ↑ Goosey-Tolfrey, Vicky (2010-01-01). Wheelchair Sport: A Complete Guide for Athletes, Coaches, and Teachers. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736086769.

- 1 2 "CLASSIFICATION GUIDE" (PDF). Swimming Australia. Swimming Australia. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Bench Press Form". International Disabled Bowls. International Disabled Bowls. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Medical Diagnostic Form" (PDF). IWAS. IWAS. Retrieved July 30, 2016.