| Wills, trusts and estates |

|---|

|

| Part of the common law series |

| Wills |

|

Sections Property disposition |

| Trusts |

|

Common types Other types

Governing doctrines |

| Estate administration |

| Related topics |

| Other common law areas |

A will contest, in the law of property, is a formal objection raised against the validity of a will, based on the contention that the will does not reflect the actual intent of the testator (the party who made the will) or that the will is otherwise invalid. Will contests generally focus on the assertion that the testator lacked testamentary capacity, was operating under an insane delusion, or was subject to undue influence or fraud. A will may be challenged in its entirety or in part.

Courts and legislation generally feel a strong obligation to uphold the final wishes of a testator, and, without compelling evidence to the contrary, "the law presumes that a will is valid and accurately reflects the wishes of the person who wrote it".[1]

A will may include an in terrorem clause, with language along the lines of "any person who contests this will shall forfeit his legacy", which operates to disinherit any person who challenges the validity of the will. Such no-contest clauses are permitted under the Uniform Probate Code, which most American states follow at least in part. However, since the clause is within the will itself, a successful challenge to the will renders the clause meaningless. Many states consider such clauses void as a matter of public policy or valid only if a will is contested without probable cause.[2]

This article mainly discusses American law and cases. Will contests are more common in the United States than in other countries. This prevalence of will contests in the U.S. is partly because the law gives people a large degree of freedom in disposing of their property and also because "a number of incentives for suing exist in American law outside of the merits of the litigation itself".[3] Most other legal traditions enforce some type of forced heirship, requiring that a testator leave at least some assets to their family, particularly the spouse and children.[4]

Standing to contest will

Typically, standing in the United States to contest the validity of a will is limited to two classes of persons:

- Those who are named on the face of the will (any beneficiary);

- Those who would inherit from the testator if the will was invalid

For example, Monica makes a will leaving $5,000 each to her husband, Chandler; her brother, Ross; her neighbor, Joey and her best friend, Rachel. Chandler tells Monica that he will divorce her if she does not disown Ross, which would humiliate her. Later, Ross tells Monica (untruthfully) that Chandler is having an affair with Phoebe, which Monica believes. Distraught, Monica rewrites her will, disowning both Chandler and Ross. The attorney who drafts the will accidentally writes the gift to Rachel as $500 instead of $5,000 and also accidentally leaves Joey out entirely.

Under such facts:

- Chandler can contest the will as the product of fraud in the inducement, because if the will is invalid, he will inherit Monica's property, as the surviving spouse.

- Ross can contest the will as the product of Chandler's undue influence, as Ross will inherit Monica's property if Chandler's behavior disqualifies Chandler from inheriting (however, many jurisdictions do not consider a threat of divorce to be undue influence).

- Rachel has standing to contest the will, as she is named in the document, but she will not be permitted to submit any evidence as to the mistake because it is not an ambiguous term. Instead, she will have to sue Monica's lawyer for legal malpractice to recover the difference.

- Finally, neither Joey nor Phoebe is someone who stands to inherit from Monica, nor is either named in the will, and so both are barred from contesting the will altogether.

Grounds for contesting will

Common grounds or reasons for contesting a will include lack of testamentary capacity, undue influence, insane delusion, fraud, duress, technical flaws and forgery.

Lack of testamentary capacity

Lack of testamentary capacity or disposing mind and memory claims are based on assertions that the testator lacked mental capacity when the will was drafted, and they are the most common types of testamentary challenges.[3] Testamentary capacity in the United States typically requires that a testator has sufficient mental acuity to understand the amount and the nature of the property, the family members and the loved ones who would ordinarily receive such property by the will, and (c) how the will disposes of such property. Under this low standard for competence, one may possess testamentary capacity but still lack mental capacity to sign other contracts.[5][6][7] Furthermore, a testator with serious dementia may have "lucid periods" and then is capable of writing or modifying a will.[8]

Other nations like Germany may have more stringent requirements for writing a will.[3] Lack of mental capacity or incompetence is typically proven by medical records, irrational conduct of the decedent, and the testimony of those who observed the decedent at the time the will was executed. Simply because an individual has a form of mental illness or disease, undergoes mental health treatment after repeated suicide attempts,[9] or exhibits eccentric behavior, does not mean the person automatically lacks the requisite mental capacity to make a will.

Undue influence

Undue influence typically involves the accusation that a trusted friend, relative, or caregiver actively procured a new will that reflects that person's own desires rather than those of the testator. Such allegations are often closely linked to lack of mental capacity: someone of sound mind is unlikely to be swayed by undue influence, pressure, manipulation, etc. As it is required for invalidation of a will, undue influence must amount to "over-persuasion, duress, force, coercion, or artful or fraudulent contrivances to such a degree that there is destruction of the free agency and will power of the one making the will.

Mere affection, kindness or attachment of one person for another may not of itself constitute undue influence."[10] For example, Florida law gives a list of the types of active procurement that will be considered in invalidating a will: presence of the beneficiary at the execution of the will; presence of the beneficiary on those occasions when the testator expressed a desire to make a will; recommendation by the beneficiary of an attorney to draw the will; knowledge of the contents of the will by the beneficiary prior to execution; giving of instructions on preparation of the will by the beneficiary to the attorney drawing the will; securing of witnesses to the will by the beneficiary; and safekeeping of the will by the beneficiary subsequent to execution.[11]

In most U.S. states, including Florida, if the challenger of a will is able to establish that it was actively procured, the burden of proof shifts to the person seeking to uphold the will to establish that the will is not the product of undue influence. However, undue influence is notoriously difficult to prove, and establishing the someone has the means, motive and inclination to exert undue influence is not enough to prove that the person in fact exerted such influence in a particular case.[12] However, attorneys are often held to a higher standard and are suspect if they assist in drafting a will that names them as a beneficiary.[13][14]

In many jurisdictions, a legal presumption of undue influence arises when there is a finding of a confidential (or fiduciary) relationship, the active procurement of the will by the beneficiary and a substantial benefit to that beneficiary, such as if a testator leaves property to the attorney who drew up the will. However, that is dependent on the circumstances of such a relationship and typically the burden is initially on the person contesting to show undue influence. Proving undue influence is difficult. In Australia, a challenger must show that the free will of the testator has been overborne by words and actions of the alleged wrong doer(s), to such an extent that the deceased’s freedom of testation has been taken away.[15]

Insane delusion

Insane delusion is another form of incapacity in which someone executes a will while strongly holding a "fixed false belief without hypothesis, having no foundation in reality."[16] Other courts have expanded on this concept by adding that the fixed false belief must be persistently adhered to against all evidence and reason,[17] and the irrational belief must have influenced the drafting or provisions of the will.[18]

In Florida, one of the most-often cited court rulings on insane delusion is from 2006.[19] In this case, the decedent executed a new will in 2005 in the hospital with severe pain and under the influence of a strong medication. She died the next day. The new will disinherited the caretaker and left the decedent's estate to several charities. The caretaker asserted that the decedent was suffering from an insane delusion at the time the will was executed and that she thus lacked testamentary capacity. The decedent's physicians testified regarding the medication that the decedent was taking and how it had changed her personality. A psychiatrist who saw the decedent opined that she was delusional when she stated that the caretaker had abandoned her and had killed her dog. To the contrary, witnesses and evidence supported the position that the caretaker visited the decedent in the hospital every day, and the caretaker gave credible testimony that she was continuing to care for the dog. Accordingly, the court set aside the will as invalid based upon insane delusion.

Duress

Duress involves some threat of physical harm or coercion upon the testator by the perpetrator that caused the execution of the will.

Fraud

There are four general elements of fraud: false representations of material facts to the testator; knowledge by the perpetrator that the representations are false; intent that the representations be acted upon and resulting injury. There are two primary types of fraud: fraud in the execution, (for example, the testator was told the will he signed was something other than a will[20][21]), and fraud in the inducement (for example, the testator is intentionally misled by a material fact that caused the testator to make a different devise from the one he would otherwise have made).

Technical flaws

A will contest may be based upon alleged failure to adhere to the legal formalities required in a particular jurisdiction. For example, some states require that wills must use specific terminology or jargon, must be notarized, must be witnessed by a certain number of persons, or witnessed by disinterested parties who are not relatives, inherit nothing in the will, and are not nominated as an executor. Additionally, the testator and witnesses must generally sign the will in each other's sight and physical presence.

For example, in Utah, a will must be "signed by the testator or in the testator's name by some other individual in the testator's conscious presence and by the testator's direction; and... signed by at least two individuals, each of whom signed within a reasonable time after he witnessed either the signing of the will... or [received] the testator's acknowledgment [that he or she actually signed the will]."[22] In a Pennsylvania case, the wills of a husband and wife were invalidated because they accidentally signed each other's wills.[23]

Forgery

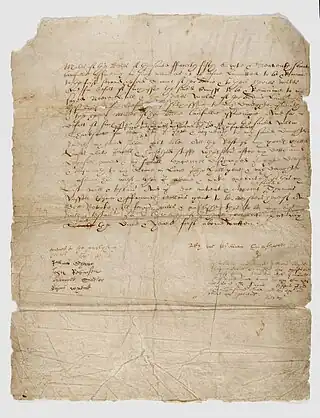

In some cases a will contest is based on allegations that the will is forged. Forgery can range from the fabrication of an entire document, including the signatures, to the insertion or modification of pages in an otherwise legitimate will.

According to a 2009 Wall Street Journal article, "charges of forgery are more common than proven cases of it. They often originate with an adult child who, feeling short-changed in a parent's will, accuses a sibling of doctoring the document".[24]

Notable cases of forged wills include the "Mormon will" allegedly written by reclusive business tycoon Howard Hughes (1905-1976), and the Howland will forgery trial (1868) in which sophisticated mathematical analysis showed that the signature on a will was most likely forged. British physician Harold Shipman killed numerous elderly patients and was caught after forging one patient's will to benefit himself.[25]

Legal inheritance rights

Some jurisdictions permit an election against the will by a widowed spouse or orphaned children. That is not a contest against the will itself (the validity of the will is irrelevant), but an alternate procedure established by statute to contest the disposition of property.

In the United Kingdom, wills are often contested on the basis that a child of the deceased (or somebody treated as such) was bequeathed nothing or less than could reasonably be expected.

Statutory Jurisdiction

Certain jurisdictions, like Australia and its States and Territories, have enacted legislation such as the Succession Act 2006 (NSW) that permits an eligible person to contest a will if it failed to adequately provide for that person's proper education, maintenance and advancement in life.[26]

Practicability

In the United States, research finds that between 0.5% and 3% of wills are contested. Despite that small percentage, given the millions of American wills probated every year it means that a substantial number of will contests occur.[4] As of the mid-1980s, the most common reason for contesting a will is undue influence and/or supposed lack of testamentary capacity, accounting for about three quarters of will contests; another 15% of will contests are based on an alleged failure to adhere to required formalities in the disputed will; the remainder of contests involve accusations of fraud, insane delusion, etc.[27]

The vast majority of will contests are not successful,[28][4] in part because most states tend to assume that a properly-executed will is valid, and a testator possesses the requisite mental capacity to execute a will unless the contesting party can demonstrate the contrary position by clear and convincing evidence.[4] Generally, proponents of a will must establish its validity by a preponderance of evidence, but those contesting a will must prevail by showing clear and convincing evidence, the latter requiring a much higher standard of proof.

Contesting a will can be expensive. According to a Boston-area estate planning attorney quoted in Consumer Reports (March, 2012), "A typical will contest will cost $10,000 to $50,000, and that's a conservative estimate".[1] Costs can increase even more if a will contest actually goes to trial, and the overall value of an estate can determine if a will contest is worth the expense. In some cases, the threat of a will contest is intended to both pressure the estate into avoiding the expense of a trial and forcing an out-of-court settlement more favorable to disgruntled heirs.[3] However, those who make frivolous or groundless objections to a will may be forced to pay the costs for both sides in the court battle.[28]

Courts do not necessarily look to fairness during will contests, and a considerable portion of will contests are initiated by those who have no cause of action justifying a court case but are instead reacting to "hurt feelings" of disinheritance.[29] In other words, just because the provisions of a will may seem "unfair" does not mean that the will is invalid. Therefore, wills cannot be challenged simply because a beneficiary believes the inheritance or lack thereof is unfair.[1] In the United States, the decedent generally has a legal right to dispose of property in any way that is legal.

Consequences

Depending on the grounds, the result of a will contest may be:

- Invalidity of the entire will, resulting in an intestacy or reinstatement of an earlier will.

- Invalidity of a clause or gift, requiring the court to apply principles of intestate succession, or to decide which beneficiary or charity receives the charitable bequest by using the equitable doctrine of cy pres.[30]

- Diminution of certain gifts and increase of other gifts to the widowed spouse or orphaned children, who would now get their elective share.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Consumer Reports Money Adviser, "How to contest a will: Do you think you were cheated out of an inheritance? You might be able to challenge the will". March 2012, accessed 2015-02-25.

- ↑ Uniform Probate Code (UPC) § 2-517. Penalty Clause for Contest, replicated at § 3‑905. Penalty Clause for Contest. Both found at University of Pennsylvania Law School website page on Uniform Probate Code. Accessed October 5, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Ronald J. Scalise Jr., Undue Influence and the Law of Wills: A Comparative Analysis, 19 Duke Journal of Comparative & International Law 41, 99 (2008).

- 1 2 3 4 Ryznar, Margaret; Devaux, Angelique (2014). "Au Revoir, Will Contests: Comparative Lessons for Preventing Will Contests". Nevada Law Journal. 14 (1): 1. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ "Anderson v. Hunt, 196 Cal.App.4th 722, 731". Google Scholar. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ In a Michigan case, the state Supreme Court decision read, "A man may believe himself to be the supreme ruler of the universe and nevertheless make a perfectly sensible disposition of his property, and the courts will sustain it when it appears that his mania did not dictate its provisions." See Fraser v. Jennison, 3 N.W. 882, 900 (Mich. 1879)

- ↑ In a Nebraska case, the court ruled that "gross eccentricity, slovenliness in dress, peculiarities of speech and manner or ill health are not facts sufficient to disqualify a person from making a will." See 'In re' Estate of Frazier, 131 Neb. 61, 73, 267 N.W. 181, 187 (1936).

- ↑ "Estate of Goetz, 253 Cal.App.2d 107 (1967)". Google Scholar. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ "In re Hatzistefanous's Estate, 77 Misc. 2d 594 (1974)". Google Scholar. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ "Heasley v. Evans, 104 So. 2d 854, 857 (Fla. 2d DCA 1958)". Google Scholar. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ White, Frank L. (Spring 1961). "Will Contests - Burden of Proof as to Undue Influence: Effect of Confidential Relationship". Marquette Law Review. 44 (10): 570. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ Core v. Core's Administrators, 124 S.E. 453 (Va. 1924).

- ↑ "Carter v. Williams, 431 S.E.2d 297 (Va. 1993)". Google Scholar. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ In re Putnam's Will, 257 N.Y. 140 (1931)

- ↑ Burns, Fiona (2002). "Undue Influence Inter Vivos And The Elderly". Melbourne University Law Review. 26 (3): 499. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ↑ Hooper v. Stokes, 145 So. 855 (Fla. 1933).

- ↑ "In Re Estate of Edwards, 433 So. 2d 1349 (Fla. 5th DCA 1983)". Google Scholar. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ In re Heaton's Will, 224 N.Y. 22 (1918)

- ↑ "Miami Rescue Mission, Inc. v. Roberts, 943 So.2d 274 (Fla. 3d DCA 2006)". Google Scholar. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ Kelly v. Settegast, 2 S.W. 870 (Tex. 1887)

- ↑ "Bailey v. Clark, 149 Ill.Dec. 89, 561 N.E.2d 367 (1990)". Google Scholar. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ Utah Code Annotated, Title 75 Chapter 2 Section 502.

- ↑ "In re Pavlinko's Estate], 394 Pa. 564 (1959)". Google Scholar. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ Dale, Arden (15 October 2009). "Forged Wills Are Now Not Just Fiction". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ "The Shipman tapes I". BBC News. 31 January 2000. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ↑ "The basics of a Will Contest :: Litigant". www.litigant.com.au. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ↑ Schoenblum, Jeffery A. (1987). "Will Contests—An Empirical Study", 22 Real Prop Prob &Tr. J. 607, 647–48.

- 1 2 Miller, Robert K. (ed). Inheritance and Wealth in America, Springer Science & Business Media, 1998, p 188.

- ↑ Williams, Geoff (2013). "Disinheriting Someone Is Not Easy", Reuters 31 Jan 2013, accessed 2015-03-07.

- ↑ Barkham, Patrick (28 July 2015). "Battle of the bequests: animal charities v disinherited relatives". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 September 2017.