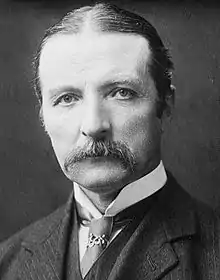

William Archer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 23 September 1856 Perth, Scotland |

| Died | 27 December 1924 (aged 68) London, England |

| Education | Middle Temple |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation(s) | Writer, theatre critic |

| Spouse |

Frances Elizabeth Trickett

(m. 1884) |

| Children | 3 sons |

| Parent |

|

William Archer (23 September 1856 – 27 December 1924) was a Scottish writer, theatre critic, and English spelling reformer based, for most of his career, in London. He was an early advocate of the plays of Henrik Ibsen, and a friend and supporter of George Bernard Shaw.

Life and career

Archer was born in Perth, the eldest boy of the nine children of Thomas Archer and his wife Grace, née Morrison. Thomas moved frequently from place to place seeking employment, and William attended schools in Perth, Lymington, Reigate and Edinburgh.[1] He spent parts of his boyhood with relatives in Norway where he became fluent in Norwegian and became acquainted with the works of Henrik Ibsen.[2]

Archer won a bursary to the University of Edinburgh to study English literature, moral and natural philosophy, and mathematics. When the family moved to Australia in 1872, he remained in Scotland as a student. While still at the university he became a leader-writer on the Edinburgh Evening News in 1875, and after a year visiting his family in Australia, he returned to Edinburgh.[1] In 1878, in accordance with his father's wishes, he moved to London to train as a barrister. He was uninterested in law, and was by now fascinated with the theatre, but he entered the Middle Temple and was called to the bar in 1883: he never practised.[1] He supported himself by working as dramatic critic of The London Figaro, and after he finished his legal studies he moved to The World, where he remained from 1884 to 1906.[1] In London he soon took a prominent literary place and exercised much influence.[3]

Archer played an important part in introducing Ibsen to the English public, starting with his translation of The Pillars of Society, produced at the Gaiety Theatre in 1880. It was the first Ibsen play to be produced in London but made little impression.[2] He also translated, alone or in collaboration, other productions of the Scandinavian stage: Ibsen's A Doll's House (1889), The Master Builder (1893, with Edmund Gosse); Edvard Brandes's A Visit (1892); Ibsen's Peer Gynt (1892, with Charles Archer); Georg Brandes "William Shakespeare"; (1895) Little Eyolf (1895); and John Gabriel Borkman (1897); and he edited Ibsen's Prose Dramas (1890–1891).[3]

In 1881, Archer met Frances Elizabeth Trickett (1855–1929), the youngest of the eight children of John Trickett, a retired engineer. They married in October 1884; the following year they had their only child, Tom (1885–1918), who was killed in action in the First World War. The marriage was enduring and companionable, although Archer began a relationship in 1891, which lasted for the rest of his life, with the actress Elizabeth Robins.[1]

In 1897, Archer, along with Robins, Henry William Massingham, and Alfred Sutro, formed the Provisional Committee to organise an association to produce plays they considered to be of high literary merit, such as Ibsen's. The association was called the "New Century Theatre" but was a disappointment by 1899, although it continued until at least 1904.[1] In 1899, a more successful association, called the Stage Society, was formed to replace it.[4]

Archer was an early friend of George Bernard Shaw, and arranged for his plays to be translated into German. An attempted collaboration on a play foundered, although Shaw later turned their joint ideas into his early work, Widower's Houses. Through Archer's influence Shaw obtained the post of art critic to The World, before becoming its music critic.[1] A biographer, J. P. Wearing, says of their relationship:

Their intimate friendship could also be very turbulent, since both men were forthright and honest. Shaw respected Archer's intelligence and integrity, and penetrated his formality and deliberately cultivated dour Scots façade. Archer thought Shaw brilliant if perverse, and concluded that he never achieved his great potential because he was too much a jester.[1]

During the First World War, Archer worked for the official War Propaganda Bureau. After the war, he achieved financial success with his play The Green Goddess, produced by Winthrop Ames at the Booth Theatre in New York City in 1921. It was a melodrama, and a popular success, although, he admitted, of much less importance to the art of the drama than his critical work.[1]

Archer died in a London nursing home in 1924 of post-operative complications after the removal of a kidney tumour. Reviewing his life and career, Wearing's summary is that Archer was "a clear, logical man whom some saw as too narrowly rationalistic", but who was perceptive, intuitive and imaginative. Wearing attributes Archer's great influence as a critic to these qualities and to the length of time for which he was engaged in the theatre and reviewing, although

[he] had his blind spots, as in his failure to understand Chekhov, Strindberg, and Shaw, but he was incorruptibly honest and unwaveringly committed to the improvement of ... the theatre. His pioneering advocacy of Ibsen in England cannot be underestimated ... although his other contributions to the theatre are equally valuable.[1]

Outside of his critical career, Archer and Walter Ripman wrote the first dictionary for the English spelling reform system NuSpelling, which would serve as a milestone in the development of SoundSpel.

Works

Critical works

- English Dramatists of To-day (1882)

- Henry Irving, a study (1883)

- About the Theatre: Essays and Studies (1886)

- Masks or Faces? A Study in the Psychology of Acting (1888)

- W. C. Macready, a biography (1890)

- Alan's Wife; a Dramatic Study in Three Scenes (1893)

- "The Theatrical World for..." (1893–97), in five volumes

- America To-day, Observations and Reflections (1900)

- Poets of the Younger Generation (1901) John Lane, the Bodley Head, London

- Real Conversations (1904)

- A National Theatre: Scheme and Estimates, with H. Granville Barker, (1907)

- Through Afro-America (1910)

- The Life, Trial, and Death of Francisco Ferrer (1911)

- Play-Making (1912)[5]

- India and the Future (1917)

- The Old Drama and the New (1923)

Essays

- The Great Analysis: A Plea for a Rational World-Order (1912). Introduction by Gilbert Murray

Plays

- War is War (1919)

- The Green Goddess (1921)

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Wearing, J.P. (2004). "Archer, William (1856–1924), theatre critic and journalist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 28 December 2017. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- 1 2 Drabble 2000, pp. 37–38

- 1 2 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ Woodfield 1984, pp. 56–58

- ↑ William Archer (1912). Play-making: A Manual of Craftsmanship. Small, Maynard. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

References

- Archer, Lt.-Col. Charles (1931). William Archer: Life, Work and Friendships. London: Allen & Unwin. (US edition: Yale University Press)

- Caton, A. R. (1936). Activity and Rest: The Life and Work of Mrs. William Archer. London: Philip Allan & Co.

- Drabble, Margaret, ed. (2000). The Oxford Companion to English Literature (sixth ed.). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861453-1.

- Whitebrook, Peter (1993). William Archer. A Biography. London: Methuen.

- Woodfield, James (1984). English Theatre in Transition, 1881–1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-93465-8.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Archer, William". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 362.

External links

Works by or about William Archer at Wikisource

Works by or about William Archer at Wikisource- William Archer on SF Encyclopedia

- Works by William Archer at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Archer at Internet Archive

- Works by William Archer at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Papers of William Archer at Edinburgh U. Library

- Archer, William (1918), India and the Future, New York: Alfred A. Knopf

- Article by Martin Quinn in Dictionary of Literary Biography

- William Archer at Library of Congress, with 128 library catalogue records