William H. Seward | |

|---|---|

Seward in 1859 | |

| 24th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 6, 1861 – March 4, 1869 | |

| President | |

| Preceded by | Jeremiah S. Black |

| Succeeded by | Elihu B. Washburne |

| United States Senator from New York | |

| In office March 4, 1849 – March 3, 1861 | |

| Preceded by | John Adams Dix |

| Succeeded by | Ira Harris |

| 12th Governor of New York | |

| In office January 1, 1839 – December 31, 1842 | |

| Lieutenant | Luther Bradish |

| Preceded by | William L. Marcy |

| Succeeded by | William C. Bouck |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Henry Seward May 16, 1801 Florida, New York, U.S. |

| Died | October 10, 1872 (aged 71) Auburn, New York, U.S. |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | Frances Miller |

| Children | 6, including Augustus, Frederick, William, Fanny, Olive (adopted) |

| Education | Union College (BA) |

| Signature | |

William Henry Seward (/ˈsuːərd/;[1] May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined opponent of the spread of slavery in the years leading up to the American Civil War, he was a prominent figure in the Republican Party in its formative years, and was praised for his work on behalf of the Union as Secretary of State during the Civil War. He also negotiated the treaty for the United States to purchase the Alaska Territory.

Seward was born in 1801 in the village of Florida, in Orange County, New York, where his father was a farmer and owned slaves. He was educated as a lawyer and moved to the Central New York town of Auburn. Seward was elected to the New York State Senate in 1830 as an Anti-Mason. Four years later, he became the gubernatorial nominee of the Whig Party. Though he was not successful in that race, Seward was elected governor in 1838 and won a second two-year term in 1840. During this period, he signed several laws that advanced the rights of and opportunities for black residents, as well as guaranteeing jury trials for fugitive slaves in the state. The legislation protected abolitionists, and he used his position to intervene in cases of freed black people who were enslaved in the South.

After many years of practicing law in Auburn, he was elected by the state legislature to the U.S. Senate in 1849. Seward's strong stances and provocative words against slavery brought him hatred in the South. He was re-elected to the Senate in 1855, and soon joined the nascent Republican Party, becoming one of its leading figures. As the 1860 presidential election approached, he was regarded as the leading candidate for the Republican nomination. Several factors, including attitudes to his vocal opposition to slavery, his support for immigrants and Catholics, and his association with editor and political boss Thurlow Weed, worked against him, and Abraham Lincoln secured the presidential nomination. Although devastated by his loss, he campaigned for Lincoln, who appointed him Secretary of State after winning the election.

Seward did his best to stop the southern states from seceding; once that failed, he devoted himself wholeheartedly to the Union cause. His firm stance against foreign intervention in the Civil War helped deter the United Kingdom and France from recognizing the independence of the Confederate States. He was one of the targets of the 1865 assassination plot that killed Lincoln and was seriously wounded by conspirator Lewis Powell. Seward remained in his post through the presidency of Andrew Johnson, during which he negotiated the Alaska Purchase in 1867 and supported Johnson during his impeachment. His contemporary Carl Schurz described Seward as "one of those spirits who sometimes will go ahead of public opinion instead of tamely following its footprints".[2]

Early life

Seward was born on May 16, 1801, in the small community of Florida, New York, in Orange County.[3] He was the fourth son of Samuel Sweezy Seward and his wife Mary (Jennings) Seward.[4] Samuel Seward was a wealthy landowner and slaveholder in New York State; slavery was not fully abolished in the state until 1827.[5] Florida, located some 60 miles (100 km) north of New York City and west of the Hudson River, was a small rural village of perhaps a dozen homes. Young Seward attended school there, and also in the nearby county seat of Goshen.[6] He was a bright student who enjoyed his studies. In later years, one of the former family slaves would relate that instead of running away from school to go home, Seward would run away from home to go to school.[7]

At the age of 15, Henry—he was known by his middle name as a boy—was sent to Union College in Schenectady, New York. Admitted to the sophomore class, Seward was an outstanding student and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. Seward's fellow students included Richard M. Blatchford, who became a lifelong legal and political associate.[8] Samuel Seward kept his son short on cash, and in December 1818—during the middle of Henry's final year at Union—the two quarreled about money. The younger Seward returned to Schenectady but soon left school in company with a fellow student, Alvah Wilson. The two took a ship from New York to Georgia, where Wilson had been offered a job as rector, or principal, of a new academy in rural Putnam County. En route, Wilson took a job at another school, leaving Seward to continue on to Eatonton in Putnam County. The trustees interviewed the 17-year-old Seward and found his qualifications acceptable.[9]

Seward enjoyed his time in Georgia, where he was accepted as an adult for the first time. He was treated hospitably but also witnessed the ill-treatment of slaves.[10] Seward was persuaded to return to New York by his family and did so in June 1819. As it was too late for him to graduate with his class, he studied law at an attorney's office in Goshen before returning to Union College, securing his degree with highest honors in June 1820.[10]

Lawyer and state senator

Early career and involvement in politics

After graduation, Seward spent much of the following two years studying law in Goshen and New York City with attorneys John Duer, John Anthon and Ogden Hoffman. He passed the bar examination in late 1822.[11] He could have practiced in Goshen, but he disliked the town and sought a practice in growing Western New York. Seward decided upon Auburn in Cayuga County, which was about 150 miles (200 km) west of Albany and 200 miles (300 km) northwest of Goshen.[12] He joined the practice of retired judge Elijah Miller, whose daughter Frances Adeline Miller was a classmate of his sister Cornelia at Emma Willard's Troy Female Seminary. Seward married Frances Miller on October 20, 1824.[13]

In 1824, Seward was journeying with his wife to Niagara Falls when one of the wheels on his carriage was damaged while they passed through Rochester. Among those who came to their aid was local newspaper publisher Thurlow Weed.[14] Seward and Weed would become closer in the years ahead as they found they shared a belief that government policies should promote infrastructure improvements, such as roads and canals.[15] Weed, deemed by some to be one of the earliest political bosses, would become a major ally of Seward. Despite the benefits to Seward's career from Weed's support, perceptions that Seward was too much controlled by Weed became a factor in the former's defeat for the Republican nomination for president in 1860.[16]

Almost from the time he settled in Auburn, Seward involved himself in politics. At that time, the political system was in flux as new parties evolved. In New York State, there were generally two factions, which went by varying names, but were characterized by the fact that Martin Van Buren led one element, and the other opposed him. Van Buren, over a quarter century, held a series of senior posts, generally in the federal government. His allies were dubbed the Albany Regency, as they governed for Van Buren while he was away.[17]

Seward originally supported the Regency, but by 1824 had broken from it, concluding that it was corrupt.[18] He became part of the Anti-Masonic Party, which became widespread in 1826 after the disappearance and death of William Morgan, a Mason in Upstate New York; he was most likely killed by fellow Masons for publishing a book revealing the order's secret rites.[19] Since the leading candidate in opposition to President John Quincy Adams was General Andrew Jackson, a Mason who mocked opponents of the order, Anti-Masonry became closely associated with opposition to Jackson, and to his policies once he was elected president in 1828.[20]

Governor DeWitt Clinton had nominated Seward as Cayuga County Surrogate in late 1827 or early 1828, but as Seward was unwilling to support Jackson, he was not confirmed by the state Senate. During the 1828 campaign, Seward made speeches in support of President Adams's re-election.[21] Seward was nominated for the federal House of Representatives by the Anti-Masons, but withdrew, deeming the fight hopeless.[22] In 1829, Seward was offered the local nomination for New York State Assembly, but again felt there was no prospect of winning. In 1830, with Weed's aid, he gained the Anti-Masonic nomination for state senator for the local district. Seward had appeared in court throughout the district, and had spoken in favor of government support for infrastructure improvements, a position popular there. Weed had moved his operations to Albany, where his newspaper, the Albany Evening Journal, advocated for Seward, who was elected by about 2,000 votes.[23]

State senator and gubernatorial candidate

Seward was sworn in as state senator in January 1831. He left Frances and their children in Auburn and wrote to her of his experiences. These included meeting former vice president Aaron Burr, who had returned to practicing law in New York following a self-imposed exile in Europe after his duel with Alexander Hamilton and treason trial. The Regency (or the Democrats, as the national party led by Jackson and supported by Van Buren, was becoming known) controlled the Senate. Seward and his party allied with dissident Democrats and others to pass some legislation, including penal reform measures, for which Seward would become known.[24][25]

During his term as state senator, Seward traveled extensively, visiting other anti-Jackson leaders, including former president Adams. He also accompanied his father Samuel Seward on a trip to Europe, where they met the political men of the day.[26] Seward hoped that the Anti-Masons would nominate Supreme Court Justice John McLean for president against Jackson's re-election bid in 1832, but the nomination fell to former Attorney General William Wirt. Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, an opponent of Jackson, was a Mason, and thus unacceptable as party standard-bearer.[27] In the aftermath of Jackson's easy victory, many of those who opposed him believed that a united front was necessary to defeat the Democrats, and the Whig Party gradually came into being. The Whigs believed in legislative action to develop the country and opposed Jackson's unilateral actions as president, which they deemed imperial.[26] Many Anti-Masons, including Seward and Weed, readily joined the new party.[28]

In preparation for the 1834 election, New York's Whigs met in Utica to determine a gubernatorial candidate. Democratic Governor William Marcy was heavily favored to be re-elected, and few prominent Whigs were anxious to run a campaign that would most likely be lost. Seward's wife and father wanted him to retire from politics to increase the income from his law practice, and Weed urged him to seek re-election to the state Senate. Nevertheless, the reluctance of others to run caused Seward to emerge as a major candidate. Weed procured Seward's triumph at the Utica convention. The election turned on national issues, most importantly President Jackson's policies. These were then popular, and in a strong year for Democrats, Seward was defeated by some 11,000 votes—Weed wrote that the Whigs were overwhelmed by illegally cast ballots.[29]

Defeated for governor and with his term in the state Senate having expired, Seward returned to Auburn and the practice of law at the start of 1835. That year, Seward and his wife undertook a lengthy trip, going as far south as Virginia. Although they were hospitably received by southerners, the Sewards saw scenes of slavery which confirmed them as its opponents.[30] The following year, Seward accepted a position as agent for the new owners of the Holland Land Company, which owned large tracts of land in Western New York, upon which many settlers were purchasing real estate on installment. The new owners were viewed as less forgiving landlords than the old, and when there was unrest, they hired Seward, popular in Western New York, in hopes of adjusting the matter. He was successful, and when the Panic of 1837 began, persuaded the owners to avoid foreclosures where possible. He also, in 1838, arranged the purchase of the company's holdings by a consortium that included himself.[31]

Van Buren had been elected president in 1836; even with his other activities, Seward had found time to campaign against him. The economic crisis came soon after the inauguration and threatened the Regency's control of New York politics.[32] Seward had not run for governor in 1836, but with the Democrats unpopular, saw a path to victory in 1838 (the term was then two years). Other prominent Whigs also sought the nomination. Weed persuaded delegates to the convention that Seward had run ahead of other Whig candidates in 1834; Seward was nominated on the fourth ballot.[33] Seward's opponent was again Marcy, and the economy the principal issue. The Whigs argued that the Democrats were responsible for the recession.[34] As it was thought improper for candidates for major office to campaign in person, Seward left most of that to Weed.[35] Seward was elected by a margin of about 10,000 votes out of 400,000 cast.[36] The victory was the most significant for the Whig Party to that point,[37] and eliminated the Regency from power in New York, permanently.[38]

Governor of New York

William Seward was sworn in as governor of New York on January 1, 1839, and inaugurated in front of a crowd of jubilant Whigs. In that era, the annual message by the New York governor was published and discussed to the extent of that of a president.[39] Seward biographer Walter Stahr wrote that his address "brimmed with his youth, energy, ambition, and optimism".[40] Seward took note of America's great unexploited resources and stated that immigration should be encouraged in order to take advantage of them. He urged that citizenship and religious liberty be granted to those who came to New York's shores.[39] At the time, New York City's public schools were run by Protestants, and used Protestant texts, including the King James Bible. Seward believed the current system was a barrier to literacy for the children of Catholic immigrants and proposed legislation to change it.[41] Education, he stated, "banishes the distinctions, old as time, of rich and poor, master and slave. It banishes ignorance and lays axe to the root of crime".[40] Seward's stance was popular among Catholic immigrants, but was disliked by nativists; their opposition would eventually help defeat his bid for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860.[42]

Although the Assembly had a Whig majority at the start of Seward's first term as governor, the party had only 13 legislators out of 32 in the state Senate. The Democrats refused to cooperate with Governor Seward except on the most urgent matters, and he initially found himself unable to advance much of his agenda.[43] Accordingly, the 1839 legislative elections were crucial to Seward's legislative hopes, and to advancing the nominations of many Whigs to state office whose posts required Senate confirmation. Both Seward and President Van Buren gave several speeches across New York State that summer. Henry Clay, one of the hopefuls for the Whig nomination for president, spent part of the summer in Upstate New York, and the two men met by chance on a ferry. Seward refused to formally visit Clay at his vacation home in Saratoga Springs in the interests of neutrality, beginning a difficult relationship between the two men. After the 1839 election, the Whigs had 19 seats, allowing the party full control of state government.[44]

Following the election, there was unrest near Albany among tenant farmers on the land owned by Dutch-descended patroons of the van Rensselaer family. These tenancies allowed the landlords privileges such as enlisting the unpaid labor of tenants, and any breach could result in termination of tenure without compensation for improvements. When sheriff's deputies in Albany County were obstructed from serving eviction writs, Seward was asked to call out the militia. After an all-night cabinet meeting, he did so, though quietly assuring the tenants that he would intervene with the legislature. This mollified the settlers, though Seward proved unable to get the legislature to pass reforming laws. This question of tenants' rights was not settled until after Seward had left office.[45]

In September 1839, a ship sailing from Norfolk, Virginia, to New York City was discovered to have an escaped slave on board. The slave was returned to his owner pursuant to the Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution, but Virginia also demanded that three free black sailors, said to have concealed the fugitive aboard ship, be surrendered to its custody. This Seward would not do, and the Virginia General Assembly passed legislation inhibiting trade with New York. With Seward's encouragement, the New York legislature passed acts in 1840 protecting the rights of blacks against Southern slave-catchers.[46] One guaranteed alleged fugitive slaves the right of a jury trial in New York to establish whether they were slaves, and another pledged the aid of the state to recover free blacks kidnapped into slavery.[47]

Seward and Van Buren were both up for re-election in 1840. Seward did not attend the December 1839 Whig National Convention in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, but Weed did on his behalf. They were determined to support General Winfield Scott for president, but when Weed concluded Scott could not win, he threw New York's support behind the eventual winner, General William Henry Harrison. This action outraged supporters of Senator Clay. These grievances would not be quickly forgotten—one supporter of the Kentuckian wrote in 1847 that he was intent on seeing the "punishment of Seward & Co. for defrauding the country of Mr. Clay in 1840".[48]

Seward was renominated for a second term by the Whig convention against Democrat William C. Bouck, a former state legislator. Seward did not campaign in person, but ran affairs behind the scenes with Weed and made his views known to voters through a Fourth of July speech and lengthy letters, declining invitations to speak, printed in the papers. In one, Seward expounded upon the importance of the log cabin—a structure evoking the common man and a theme that the Whigs used heavily in Harrison's campaign—where Seward had always found a far warmer welcome than in the marble palaces of the well-to-do (evoking Van Buren). Both Harrison and Seward were elected.[49] Although Seward would serve for nearly thirty more years in public life, his name would never again pass before the voters.[50]

In his second term, Seward was involved with the trial of Alexander McLeod, who had boasted of involvement in the 1837 Caroline Affair, in which Canadians came across the Niagara River and sank the Caroline, a steamboat being used to supply William Lyon Mackenzie's fighters during the Upper Canada Rebellion. McLeod was arrested, but the British Foreign Minister, Lord Palmerston, demanded his release. McLeod, who was part of the Canadian colonial militia, could not be held responsible for actions taken under orders. Although the Van Buren administration had agreed with Seward that McLeod should be tried under state law, its successor did not and urged that charges against McLeod be dropped. A series of testy letters were exchanged between Governor Seward and Harrison's Secretary of State Daniel Webster, and also between the governor and the new president John Tyler, who succeeded on Harrison's death after a month in office. McLeod was tried and acquitted in late 1841. Stahr pointed out that Seward got his way in having McLeod tried in a state court, and the diplomatic experience served him well as Secretary of State.[51]

Seward continued his support of blacks, signing legislation in 1841 to repeal a "nine-month law" that allowed slaveholders to bring their slaves into the state for a period of nine months before they were considered free. After this, slaves brought to the state were immediately considered freed. Seward also signed legislation to establish public education for all children, leaving it up to local jurisdictions as to how that would be supplied (some had segregated schools).[47]

Out of office

As governor, Seward incurred considerable personal debt not only because he had to live beyond his salary to maintain the lifestyle expected of the office, but also because he could not pay down his obligation from the land company purchase. At the time he left office, he owed $200,000. Returning to Auburn, he absorbed himself in a profitable law practice. He did not abandon politics and received former president Adams at the Seward family home in 1843.[52]

According to his biographer, John M. Taylor, Seward picked a good time to absent himself from electoral politics, as the Whig Party was in turmoil. President Tyler, a former Democrat, and Senator Clay each claimed leadership of the Whig Party and, as the two men differed over such issues as whether to re-establish the Bank of the United States, party support was divided. The abolitionist movement attracted those who did not want to be part of a party led by slavery-supporting Southerners. In 1844, Seward was asked to run for president by members of the Liberty Party; he declined and reluctantly supported the Whig nominee, Clay. The Kentuckian was defeated by Democrat James K. Polk. The major event of Polk's administration was the Mexican–American War; Seward did not support this, feeling that the price in blood was not worth the increase in territory, especially as southerners were promoting this acquisition to expand territory for slavery.[53]

In 1846, Seward became the center of controversy in Auburn when he defended, in separate cases, two felons accused of murder. Henry Wyatt, a white man, was charged with fatally stabbing a fellow inmate in prison; William Freeman, a black, was accused of breaking into a house after his release and stabbing four people to death. In both cases, the defendants were likely mentally ill and had been abused while in prison. Seward, having long been an advocate of prison reform and better treatment for the insane, sought to prevent each man from being executed by using the relatively new defense of insanity. Seward gained a hung jury in Wyatt's first trial, though he was subsequently convicted in a retrial and executed despite Seward's efforts to secure clemency. Freeman was convicted, though Seward gained a reversal on appeal. There was no second Freeman trial, as officials were convinced of his insanity. Freeman died in prison in late 1846.[54] In the Freeman case, invoking mental illness and racial issues, Seward argued, "he is still your brother, and mine, in form and color accepted and approved by his Father, and yours, and mine, and bears equally with us the proudest inheritance of our race—the image of our Maker. Hold him then to be a Man."[55]

Although they were locally contentious, the trials boosted Seward's image across the North. He gained further publicity in association with Ohioan Salmon P. Chase when handling the unsuccessful appeal in the United States Supreme Court of John Van Zandt, an anti-slavery advocate sued by a slaveowner for assisting blacks in escaping on the Underground Railroad. Chase was impressed with Seward, writing that the former New York governor "was one of the very first public men in our country. Who but himself would have done what he did for the poor wretch Freeman?"[56]

The main Whig contenders in 1848 were Clay again, and two war hero generals with little political experience, Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor. Seward supported General Taylor. The former governor was less enthusiastic about the vice-presidential candidate, New York State Comptroller Millard Fillmore, a rival of his from Buffalo. Nevertheless, he campaigned widely for the Whigs against the Democratic presidential candidate, former Michigan senator Lewis Cass. The two major parties did not make slavery an issue in the campaign. The Free Soil Party, mostly Liberty Party members and some Northern Democrats, nominated former president Van Buren. The Taylor/Fillmore ticket was elected, and the split in the New York Democratic Party allowed the Whigs to capture the legislature.[57]

State legislatures elected U.S. senators until the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913. One of New York's seats was up for election in 1849, and a Whig would likely be elected to replace John Adams Dix. Seward, with Weed's counsel, decided to seek the seat. When legislators convened in January 1849, he was spoken of as the favorite. Some opposed him as too extreme on slavery issues and intimated that he would not support the slaveholding President-elect Taylor, a Louisianan. Weed and Seward worked to dispel these concerns, and when the vote for the Senate seat took place, the former governor received five times the vote of the nearest other candidate, gaining election on the first ballot.[57]

U.S. Senator

First term

William Seward was sworn in as senator from New York on March 5, 1849, during the brief special session called to confirm President Taylor's Cabinet nominees. Seward was seen as having influence over Taylor. Taking advantage of an acquaintance with Taylor's brother, Seward met with the former general several times before Inauguration Day (March 4) and was friendly with Cabinet officers. Taylor hoped to gain the admission of California to the Union, and Seward worked to advance his agenda in the Senate.[58]

The regular session of Congress that began in December 1849 was dominated by the issue of slavery. Senator Clay advanced a series of resolutions, which became known as the Compromise of 1850, giving victories to both North and South. Seward opposed the pro-slavery elements of the Compromise, and in a speech on the Senate floor on March 11, 1850, invoked a "higher law than the Constitution". The speech was widely reprinted and made Seward the leading anti-slavery advocate in the Senate.[59] President Taylor took a stance sympathetic to the North, but his death in July 1850 caused the accession of the pro-Compromise Fillmore and ended Seward's influence over patronage. The Compromise passed, and many Seward adherents in federal office in New York were replaced by Fillmore appointees.[60]

Although Clay had hoped the Compromise would be a final settlement on the matter of slavery that could unite the nation, it divided his Whig Party, especially when the 1852 Whig National Convention endorsed it to the anger of liberal northerners like Seward. The major candidates for the presidential nomination were President Fillmore, Senator Daniel Webster, and General Scott. Seward supported Scott, who he hoped would, like Harrison, unite enough voters behind a military hero to win the election. Scott gained the nomination, and Seward campaigned for him. The Whigs were unable to reconcile over slavery, whereas the Democrats could unite behind the Compromise; the Whigs won only four states, and former New Hampshire senator Franklin Pierce was elected president. Other events, such as the 1852 publication of Uncle Tom's Cabin and Northern anger over the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act (an element of the Compromise), widened the divide between North and South.[61]

Seward's wife Frances was deeply committed to the abolitionist movement. In the 1850s, the Seward family opened their Auburn home as a safehouse to fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad. Seward's frequent travel and political work suggest that it was Frances who played the more active role in Auburn abolitionist activities. In the excitement following the rescue and safe transport of fugitive slave William "Jerry" Henry in Syracuse on October 1, 1851, Frances wrote to her husband, "two fugitives have gone to Canada—one of them our acquaintance John".[62] Another time she wrote, "A man by the name of William Johnson will apply to you for assistance to purchase the freedom of his daughter. You will see that I have given him something by his book. I told him I thought you would give him more."[63]

In January 1854, Democratic Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas introduced his Kansas–Nebraska Bill. This would permit territories to choose whether to join the Union as free or slave states, and effectively repeal the Missouri Compromise forbidding slavery in new states north of 36° 30′ North latitude. Seward was determined to defeat what he called "this infamous Nebraska Bill," and worked to ensure the final version of the bill would be unpalatable to enough senators, North and South, to defeat it. Seward spoke against the bill both on initial consideration in the Senate and when the bill returned after reconciliation with the House.[64] The bill passed into law, but northerners had found a standard around which they could rally. Those in the South defended the new law, arguing that they should have an equal stake through slavery in the territories their blood and money had helped secure.[65]

Second term

The political turmoil engendered by the North–South divide split both major parties and led to the founding of new ones. The American Party (known as the Know Nothings) contained many nativists and pursued an anti-immigrant agenda. The Know Nothings did not publicly discuss party deliberations (thus, they knew nothing). They disliked Seward, and an uncertain number of Know Nothings sought the Whig nomination to legislative seats. Some made clear their stance by pledging to vote against Seward's re-election, but others did not. Although the Whigs won a majority in both houses of the state legislature, the extent of their support for Seward as a US senator was unclear. When the election was held by the legislature in February 1855, Seward won a narrow majority in each house. The opposition was scattered, and a Know Nothing party organ denounced two dozen legislators as "traitors".[66]

The Republican Party had been founded in 1854, in reaction to the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Its anti-slavery stance was attractive to Seward, but he needed the Whig structure in New York to get re-elected.[67] In September 1855, the New York Whig and Republican parties held simultaneous conventions that quickly merged into one. Seward was the most prominent figure to join the new party and was spoken of as a possible presidential candidate in 1856. Weed, however, did not feel that the new party was strong enough on a national level to secure the presidency, and advised Seward to wait until 1860.[68] When Seward's name was mentioned at the 1856 Republican National Convention, a huge ovation broke out.[69] In the 1856 presidential election, the Democratic candidate, former Pennsylvania senator James Buchanan, defeated the Republican, former California senator John C. Frémont, and the Know Nothing candidate, former president Fillmore.[70]

The 1856 campaign played out against the backdrop of "Bleeding Kansas", the violent efforts of pro- and anti-slavery forces to control the government in Kansas Territory and determine whether it would be admitted as a slave or free state. This violence spilled over into the Senate chamber itself after Republican Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner delivered an incendiary speech against slavery, making personal comments against South Carolina Senator Andrew P. Butler. Sumner had read a draft of the speech to Seward, who had advised him to omit the personal references. Two days after the speech, Butler's nephew, Congressman Preston Brooks entered the chamber and beat Sumner with a cane, injuring him severely. Although some southerners feared the propaganda value of the incident in the North, most lionized Brooks as a hero. Many northerners were outraged, though some, including Seward, felt that Sumner's words against Butler had unnecessarily provoked the attack.[71][72] Some Southern newspapers felt that the Sumner precedent might usefully be applied to Seward; the Petersburg Intelligencer, a Virginia periodical, suggested that "it will be very well to give Seward a double dose at least every other day".[73]

In a message to Congress in December 1857, President Buchanan advocated the admission of Kansas as a slave state under the Lecompton Constitution, passed under dubious circumstances. This split the Democrats: the administration wanted Kansas admitted; Senator Douglas demanded a fair ratification vote.[74] The Senate debated the matter through much of early 1858, though few Republicans spoke at first, content to watch the Democrats tear their party to shreds over the issue of slavery.[75] The issue was complicated by the Supreme Court's ruling the previous year in Dred Scott v. Sandford that neither Congress nor a local government could ban slavery in the territories.[76]

In a speech on March 3 in the Senate, Seward "delighted Republican ears and utterly appalled administration Democrats, especially the Southerners".[77] Discussing Dred Scott, Seward accused Buchanan and Chief Justice Roger B. Taney of conspiring to gain the result and threatened to reform the courts to eliminate Southern power.[77] Taney later told a friend that if Seward had been elected in 1860, he would have refused to administer the oath of office. Buchanan reportedly denied the senator access to the White House.[78] Seward predicted slavery was doomed:

The interest of the white races demands the ultimate emancipation of all men. Whether that consummation shall be allowed to take effect, with needful and wise precautions against sudden change and disaster, or be hurried on by violence, is all that remains for you to decide.[79]

Southerners saw this as a threat, by the man deemed the likely Republican nominee in 1860, to force change on the South whether it liked it or not.[80] Statehood for Kansas failed for the time being,[81] but Seward's words were repeatedly cited by Southern senators as the secession crisis grew.[82] Nevertheless, Seward remained on excellent personal terms with individual southerners such as Mississippi's Jefferson Davis. His dinner parties, where those from both sides of the sectional divide mingled, were a Washington legend.[83]

With an eye to a presidential bid in 1860, Seward tried to appear a statesman who could be trusted by both North and South.[84] Seward did not believe the federal government could mandate emancipation but that it would develop by action of the slave states as the nation urbanized and slavery became uneconomical, as it had in New York. Southerners still believed that he was threatening the forcible ending of slavery.[85] While campaigning for Republicans in the 1858 midterm elections, Seward gave a speech at Rochester that proved divisive and quotable, alleging that the U.S. had two "antagonistic systems [that] are continually coming into closer contact, and collision results ... It is an irrepressible conflict between opposing and enduring forces, and it means that the United States must and will, sooner or later, become entirely either a slave-holding nation, or entirely a free-labor nation."[86] White southerners saw the "irrepressible conflict" speech as a declaration of war, and Seward's vehemence ultimately damaged his chances of gaining the presidential nomination.[87]

Election of 1860

Candidate for the nomination

In 1859, Seward was advised by his political supporters that he would be better off avoiding additional controversial statements, and left the country for an eight-month tour of Europe and the Middle East. Seward spent two months in London, meeting with the Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, and was presented at Court to Queen Victoria.[88] Seward returned to Washington in January 1860 to find controversy: that some southerners blamed him for his rhetoric, which they believed had inspired John Brown to try to start a slave insurrection. Brown was captured and executed; nevertheless, Mississippi representatives Reuben Davis and Otho Singleton each stated that if Seward or another Radical Republican was elected, he would meet with the resistance of a united South.[89] To rebut such allegations, and to set forth his views in the hope of receiving the nomination, Seward made a major speech in the Senate on February 29, 1860, which most praised, though white southerners were offended, and some abolitionists also objected because the senator, in his speech, said that Brown was justly punished. The Republican National Committee ordered 250,000 copies in pamphlet form, and eventually twice that many were printed.[90]

Weed sometimes expressed certainty that Seward would be nominated; at other times he expressed gloom at the thought of the convention fight.[91] He had some reason for doubt, as word from Weed's agents across the country was mixed. Many in the Midwest did not want the issue of slavery to dominate the campaign, and with Seward as the nominee, it inevitably would. The Know Nothing Party was still alive in the Northeast, and was hostile to Seward for his pro-immigrant stance, creating doubts as to whether Seward could win Pennsylvania and New Jersey, where there were many nativists, in the general election. These states were crucial to a Republican nominee faced with a Solid South. Conservative factions in the evolving Republican Party opposed Seward.[92]

Convention

There were no primaries in 1860, no way to be certain how many delegates a candidate might receive. Nevertheless, going into the 1860 Republican National Convention in May in Chicago, Seward was seen as the overwhelming favorite. Others spoken of for the nomination included Ohio Governor Salmon P. Chase, former Missouri congressman Edward Bates, and former Illinois congressman Abraham Lincoln.[93]

Seward stayed in Auburn during the convention;[94] Weed was present on his behalf and worked to shore up Seward's support. He was amply supplied with money: business owners had eagerly given, expecting Seward to be the next president. Weed's reputation was not entirely positive; he was believed corrupt by some, and his association both helped and hurt Seward.[16]

.jpg.webp)

Enemies such as publisher and former Seward ally Horace Greeley cast doubts as to Seward's electability in the battleground states of Illinois, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. Lincoln had worked hard to gain a reputation as a moderate in the party and hoped to be seen as a consensus second choice, who might be successful in those critical states, of which the Republicans had to win three to secure the election. Lincoln's men, led by his friend David Davis, were active on his behalf. As Lincoln had not been seen as a major candidate, his supporters had been able to influence the decision to hold the convention in his home state,[95] and surrounded the New York delegation, pro-Seward, with Lincoln loyalists. They were eventually successful in gaining the support of the delegations from the other battleground states, boosting delegates' perceptions of Lincoln's electability. Although Lincoln and Seward shared many views, Lincoln, out of office since 1849, had not excited opposition as Seward had in the South and among Know Nothings. Lincoln's views on nativism, which he opposed, were not public.[96]

On the first ballot, Seward had 173½ votes to Lincoln's 102, with 233 needed to nominate. Pennsylvania shifted its vote to Lincoln on the second ballot, and Seward's lead was cut to 184½ to 181. On the third, Lincoln had 231½ to Seward's 180 after the roll call, but Ohio changed four votes from Chase to Lincoln, giving the Illinoian the nomination and starting a small stampede; the nomination was eventually made unanimous.[97] By the accounts of witnesses, when word reached Seward by telegraph he calmly remarked that Lincoln had some of the attributes needed to be president, and would certainly be elected.[97]

Campaigning for Lincoln

Despite his public nonchalance, Seward was devastated by his convention loss, as were many of his supporters. The New Yorker was the best-known and most popular Republican, and his defeat shocked many in the North, who felt that Lincoln had been nominated through chicanery. Although Seward sent a letter stating Weed was not to blame, Seward's political manager took the defeat hard.[98] Seward was initially inclined to retire from public life but received many letters from supporters: distrustful of Lincoln, they urged Seward to remain involved in politics.[99] On his way to Washington to return to Senate duties, he stopped in Albany to confer with Weed, who had gone to Lincoln's home in Springfield, Illinois, to meet with the candidate, and had been very impressed at Lincoln's political understanding.[100] At the Capitol, Seward received sympathy even from sectional foes such as Jefferson Davis.[99]

Lincoln faced three major opponents. A split in the Democratic Party had led northerners to nominate Senator Douglas, while southerners chose Vice President John C. Breckinridge. The Constitutional Union Party, a new party consisting mostly of former Southern Whigs, selected former Tennessee senator John Bell. As Lincoln would not even be on the ballot in ten southern states, he needed to win almost every northern state to take the presidency.[101] Douglas was said to be strong in Illinois and Indiana, and if he took those, the election might be thrown into the House of Representatives.[102] Seward was urged to undertake a campaign tour of the Midwest in support of Lincoln and did so for five weeks in September and October, attracting huge crowds. He journeyed by rail and boat as far north as Saint Paul, Minnesota, into the border state of Missouri at St. Louis, and even to Kansas Territory, though it had no electoral votes to cast in the election. When the train passed through Springfield, Seward and Lincoln were introduced, with Lincoln appearing "embarrassed" and Seward "constrained".[103] In his oratory, Seward spoke of the U.S. as a "tower of freedom", a Union that might even come to include Canada, Latin America, and Russian America.[104]

New York was key to the election; a Lincoln loss there would deadlock the Electoral College. Soon after his return from his Midwest tour, Seward embarked on another, speaking to large crowds across the state of New York. At Weed's urging, he went to New York City and gave a patriotic speech before a large crowd on November 3, only three days before the election.[105] On Election Day, Lincoln carried most Northern states, while Breckinridge took the Deep South, Bell three border states, and Douglas won Missouri—the only state Seward campaigned in that Lincoln did not win. Lincoln was elected.[106]

Secession crisis

Lincoln's election had been anticipated in Southern states, and South Carolina and other Deep South states began to call conventions for the purpose of secession. In the North, there was dissent over whether to offer concessions to the South to preserve the Union, and if conciliation failed, whether to allow the South to depart in peace. Seward favored compromise. He had hoped to remain at home until the New Year, but with the deepening crisis left for Washington in time for the new session of Congress in early December.[107]

The usual tradition was for the leading figure of the winning party to be offered the position of Secretary of State, the most senior Cabinet post. Seward was that person, and around December 12, the vice president-elect, Maine Senator Hannibal Hamlin, offered Seward the position on Lincoln's behalf. At Weed's advice, Seward was slow to formally accept, doing so on December 28, 1860, though well before Inauguration Day, March 4, 1861.[108] Lincoln remained in Illinois until mid-February, and he and Seward communicated by letter.[109][110]

As states in the Deep South prepared to secede in late 1860, Seward met with important figures from both sides of the sectional divide.[111] Seward introduced a proposed constitutional amendment preventing federal interference with slavery. This was done at Lincoln's private request; the president-elect hoped that the amendment, and a change to the Fugitive Slave Act to allow those captured a jury trial, would satisfy both sides. Congressmen introduced many such proposals, and Seward was appointed to a committee of 13 senators to consider them. Lincoln was willing to guarantee the security of slavery in the states that currently had it, but he rejected any proposal that would allow slavery to expand. It was increasingly clear that the deep South was committed to secession; the Republican hope was to provide compromises to keep the border slave states in the Union. Seward voted against the Crittenden Compromise on December 28, but quietly continued to seek a compromise that would keep the border states in the Union.[112]

Seward gave a major speech on January 12, 1861. By then, he was known to be Lincoln's choice as Secretary of State, and with Lincoln staying silent, it was widely expected that he would propound the new administration's plan to save the Union. Accordingly, he spoke to a crowded Senate, where even Jefferson Davis attended despite Mississippi's secession, and to packed galleries.[113] He urged the preservation of the Union, and supported an amendment such as the one he had introduced, or a constitutional convention, once passions had cooled. He hinted that New Mexico Territory might be a slave state, and urged the construction of two transcontinental railroads, one northern, one southern. He suggested the passage of legislation to bar interstate invasions such as that by John Brown. Although Seward's speech was widely applauded, it gained a mixed reaction in the border states to which he had tried to appeal. Radical Republicans were not willing to make concessions to the South, and were angered by the speech.[114] Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, a radical, warned that if Lincoln, like Seward, ignored the Republican platform and tried to purchase peace through concessions, he would retire, as too old[lower-alpha 1] to bear the years of warfare in the Republican Party that would result.[115]

Lincoln applauded Seward's speech, which he read in Springfield, but refused to approve any compromise that could lead to a further expansion of slavery. Once Lincoln left Springfield on February 11, he gave speeches, stating in Indianapolis that it would not be coercing a state if the federal government insisted on retaining or retaking property that belonged to it.[116] This came as the United States Army still held Fort Sumter; the president-elect's words upset moderate southerners. Virginia Congressman Sherrard Clemens wrote,

Mr. Lincoln, by his speech in the North, has done vast harm. If he will not be guided by Mr. Seward but puts himself in the hands of Mr. Chase and the ultra [that is, Radical] Republicans, nothing can save the cause of the Union in the South.[117]

Lincoln arrived in Washington, unannounced and incognito, early on the morning of February 23, 1861. Seward had been advised by General Winfield Scott that there was a plot to assassinate Lincoln in Baltimore when he passed through the city. Senator Seward sent his son Frederick to warn Lincoln in Philadelphia, and the president-elect decided to travel alone but for well-armed bodyguards. Lincoln travelled without incident and came to regret his decision as he was widely mocked for it. Later that morning, Seward accompanied Lincoln to the White House, where he introduced the Illinoisan to President Buchanan.[118]

Seward and Lincoln differed over two issues in the days before the inauguration: the composition of Lincoln's cabinet, and his inaugural address. Given a draft of the address, Seward softened it to make it less confrontational toward the South; Lincoln accepted many of the changes, though he gave it, according to Seward biographer Glyndon G. Van Deusen, "a simplicity and a poetic quality lacking in Seward's draft".[119] The differences regarding the Cabinet revolved around the inclusion of Salmon Chase, a radical. Lincoln wanted all elements of the party, as well as representation from outside it; Seward opposed Chase, as well as former Democrats such as Gideon Welles and Montgomery Blair. Seward did not get his way, and gave Lincoln a letter declining the post of Secretary of State.[120] Lincoln felt, as he told his private secretary, John Nicolay, that he could not "afford to let Seward take the first trick".[121] No reply or acknowledgment was made by Lincoln until after the inaugural ceremonies were over on March 4, when he asked Seward to remain. Seward did[122] and was both nominated and confirmed by the Senate, with minimal debate, on March 5, 1861.[123]

Secretary of State

Lincoln administration

War breaks out

Lincoln faced the question of what to do about Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, held by the Army against the will of South Carolinians, who had blockaded it. The fort's commander, Major Robert Anderson, had sent word that he would run out of supplies. Seward, backed by most of the Cabinet, recommended to Lincoln that an attempt to resupply Sumter would be provocative to the border states, that Lincoln hoped to keep from seceding. Seward hinted to the commissioners who had come to Washington on behalf of the Confederacy that Sumter would be surrendered. Lincoln was loath to give up Sumter, feeling it would only encourage the South in its insurgency.[124]

With the Sumter issue unresolved, Seward sent Lincoln a memorandum on April 1, proposing various courses of action, including possibly declaring war on France and Spain if certain conditions were not met, and reinforcing the forts along the Gulf of Mexico. In any event, vigorous policies were needed and the president must either establish them himself or allow a Cabinet member to do so, with Seward making it clear he was willing to do it.[125] Lincoln drafted a reply indicating that whatever policy was adopted, "I must do it", though he never sent it, but met with Seward instead, and what passed between them is not known.[126] Seward's biographers make the point that the note was sent to a Lincoln who had not yet proved himself in office.[127][128]

Lincoln decided on expeditions to try to relieve Sumter and Florida's Fort Pickens. Meanwhile, Seward was assuring Justice John Archibald Campbell, the intermediary with the Confederate commissioners who had come to Washington in an attempt to secure recognition, that no hostile action would be taken. Lincoln sent a notification to South Carolina's governor of the expedition, and on April 12, Charleston's batteries began firing on Sumter, beginning the Civil War.[129]

Diplomacy

When the war started, Seward turned his attention to making sure that foreign powers did not interfere in the conflict.[130] When the Confederacy announced in April 1861 that it would authorize privateers, Seward sent word to the American representatives abroad that the U.S. would become party to the Paris Declaration Respecting Maritime Law of 1856. This would outlaw such vessels, but Britain required that, if the U.S. were to become a party, the ratification would not require action to be taken against Confederate vessels.[131]

The Palmerston government considered recognizing the Confederacy as an independent nation. Seward was willing to wage war against Britain if it did and drafted a strong letter for the American Minister in London, Charles Francis Adams, to read to the Foreign Secretary, Lord Russell. Seward submitted it to Lincoln, who, realizing that the Union was in no position to battle both the South and Britain, toned it down considerably, and made it merely a memorandum for Adams's guidance.[132]

In May 1861, Britain and France declared the South to be belligerents by international law, and their ships were entitled to the same rights as U.S.-flagged vessels, including the right to remain 24 hours in neutral ports.[133] Nevertheless, Seward was pleased that both nations would not meet with Confederate commissioners or recognize the South as a nation. Britain did not challenge the Union blockade of Confederate ports, and Seward wrote that if Britain continued to avoid interfering in the war, he would not be overly sensitive to what wording they used to describe their policies.[134]

In November 1861, the USS San Jacinto, commanded by Captain Charles Wilkes, intercepted the British mail ship RMS Trent and removed two Confederate diplomats, James Mason and John Slidell. They were held in Boston amid jubilation in the North and outrage in Britain. The British minister in Washington, Lord Lyons, demanded their release, as the U.S. had no right to stop a British-flagged ship traveling between neutral ports. The British drew up war plans to attack New York and sent reinforcements to Canada. Seward worked to defuse the situation. He persuaded Lyons to postpone delivering an ultimatum and told Lincoln that the prisoners would have to be released. Lincoln did let them go, reluctantly, on technical grounds.[135] Relations between the U.S. and Britain soon improved; in April 1862, Seward and Lyons signed a treaty they had negotiated allowing each nation to inspect the other's ships for contraband slaves.[136] In November 1862, with America's image in Britain improved by the issuance of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, the British cabinet decided against recognition of the Confederacy as a nation.[137]

Despite Britain's neutrality, Confederate agents in Britain had arranged for the purchases of arms to be delivered to Confederate ports through blockade runners as well as the construction of Confederate warships, most notably the CSS Alabama, which ravaged Union shipping after her construction in 1862. With two more such vessels under construction the following year, supposedly for French interests, Seward pressed Palmerston not to allow the warships to leave port, and, nearly complete, they were seized by British officials in October 1863.[138] However, Britain's complicity in allowing its blockade runners loaded with weapons to Confederate ports lengthened the Civil War by two years and killed 400,000 more Americans. This caused strained relations between the UK and the U.S.[139][140][141][142][143]

Involvement in wartime detentions

From the start of the war until early 1862, when responsibility was passed to the War Department, Seward was in charge of determining who should be detained without charges or trial. Approximately 800 men and a few women, believed to be Southern sympathizers or spies, were detained, usually at the initiation of local officials. Once Seward was informed, he would often order that the prisoner be transferred to federal authorities. Seward was reported to have boasted to Lord Lyons that "I can touch a bell on my right hand, and order the arrest of a citizen ... and no power on earth, except that of the President, can release them. Can the Queen of England do so much?"[lower-alpha 2][144]

In September 1861, Maryland legislators planned to vote to leave the Union. Seward took action against them: his son Frederick, the United States Assistant Secretary of State, reported to his father that the disloyal legislators were in prison.[145] On the evidence provided by detective Allen Pinkerton, Seward in 1862 ordered the arrest of Rose Greenhow, a Washington socialite with Confederate sympathies. Greenhow had sent a stream of reports south, which continued even after she was placed under house arrest. From Washington's Old Capitol Prison, the "Rebel Rose" provided newspaper interviews until she was allowed to cross into Confederate territory.[146]

When Seward received allegations that former president Pierce was involved in a plot against the Union, he asked Pierce for an explanation. Pierce indignantly denied it. The matter proved to be a hoax, and the administration was embarrassed. On February 14, 1862, Lincoln ordered that responsibility for detentions be transferred to the War Department, ending Seward's part in them.[147]

Relationship with Lincoln

Seward had mixed feelings about the man who had blocked him from the presidency. One story is that when Seward was told that to deny Carl Schurz an office would disappoint him, Seward angrily stated, "Disappointment! You speak to me of disappointment! To me, who was justly entitled to the Republican nomination for the presidency, and who had to stand aside and see it given to a little Illinois lawyer!"[148] Despite his initial reservations about Lincoln's abilities, he came to admire Lincoln as the president grew more confident in his job. Seward wrote to his wife in June 1861, "Executive skill and vigor are rare qualities. The President is the best of us, but he needs constant and assiduous cooperation."[149] According to Goodwin, "Seward would become his most faithful ally in the cabinet ... Seward's mortification at not having received his party's nomination never fully abated, but he no longer felt compelled to belittle Lincoln to ease his pain."[150] Lincoln, a one-term congressman, was inexperienced in Washington ways and relied on Seward's advice on protocol and social etiquette.[151]

The two men built a close personal and professional relationship. Lincoln fell into the habit of entrusting Seward with tasks not within the remit of the State Department, for example asking him to examine a treaty with the Delaware Indians. Lincoln would come to Seward's house and the two lawyers would relax before the fire, chatting. Seward began to feature in the president's humorous stories. For example, Lincoln would tell of Seward remonstrating with the president, whom he found polishing his boots, "In Washington, we do not blacken our own boots," with Lincoln's response, "Indeed, then whose boots do you blacken, Mr. Secretary?"[152]

Other cabinet members became resentful of Seward, who seemed to be always present when they discussed their departments' concerns with Lincoln, yet they were never allowed to be there when the two men discussed foreign affairs. Seward announced when cabinet meetings would be; his colleagues eventually persuaded Lincoln to set a regular date and time for those sessions.[153] Seward's position on the Emancipation Proclamation when Lincoln read it to his cabinet in July 1862 is uncertain; Secretary of War Edwin Stanton wrote at the time that Seward opposed it in principle, feeling the slaves should simply be freed as Union armies advanced. Two later accounts indicate that Seward felt that it was not yet time to issue it, and Lincoln did wait until after the bloody stalemate at Antietam that ended Confederate General Robert E. Lee's incursion into the North to issue it. In the interim, Seward cautiously investigated how foreign powers might react to such a proclamation, and learned it would make them less likely to interfere in the conflict.[154]

Seward was not close to Lincoln's wife Mary, who by some accounts had opposed his appointment as Secretary of State. Mary Lincoln developed such a dislike for Seward that she instructed her coachman to avoid passing by the Seward residence. The Secretary of State enjoyed the company of the younger Lincoln boys, Willie and Tad, presenting them with two cats from his assortment of pets.[155]

Seward accompanied Lincoln to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in November 1863, where Lincoln was to deliver a short speech, that would become famous as the Gettysburg Address. The night before the speech, Lincoln met with Seward. There is no surviving evidence that Seward authored any changes: he stated after the address, when asked if had had any hand in it, that only Lincoln could have made that speech. Seward also proposed to Lincoln that he proclaim a day of national thanksgiving, and drafted a proclamation to that effect. Although post-harvest thanksgiving celebrations had long been held, this first formalized Thanksgiving Day as a national observance.[156]

1864 election; Hampton Roads Conference

It was far from certain that Lincoln would even be nominated in 1864, let alone re-elected, as the tide of war, though generally favoring the North, washed back and forth. Lincoln sought nomination by the National Union Party, composed of Republicans and War Democrats. No one proved willing to oppose Lincoln, who was nominated. Seward was by then unpopular among many Republicans and opponents sought to prompt his replacement by making Lincoln's running mate former New York Democratic senator Daniel S. Dickinson; under the political customs of the time, one state could not hold two positions as prestigious as vice president and Secretary of State. Administration forces turned back Dickinson's bid, nominating instead Military Governor of Tennessee Andrew Johnson, with whom Seward had served in the Senate. Lincoln was re-elected in November; Seward sat with Lincoln and the assistant presidential secretary, John Hay, as the returns came in.[157]

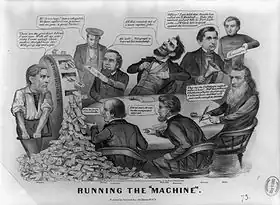

An 1864 cartoon mocking Lincoln's cabinet depicts Seward, William Fessenden, Lincoln, Edwin Stanton, Gideon Welles and other members

In January 1865, Francis Preston Blair, father of former Lincoln Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, went, with Lincoln's knowledge, to the Confederate capital of Richmond to propose to Davis that North and South unite to expel the French from their domination of Mexico. Davis appointed commissioners (Vice President Alexander Stephens, former U.S. Supreme Court justice Campbell, and former Confederate Secretary of State Robert M. T. Hunter) to negotiate. They met with Lincoln and Seward at the Hampton Roads Conference the following month. Lincoln would settle for nothing short of a cessation of resistance to the federal government and an end to slavery; the Confederates would not even concede that they and the Union were one nation. There was much friendly talk, as most of them had served together in Washington, but no agreement.[158] After the conference broke up, Seward sent a bucket of champagne to the Confederates, conveyed by a black oarsman in a rowboat, and called to the southerners, "keep the champagne, but return the Negro."[159]

Assassination attempt

John Wilkes Booth had originally planned to kidnap Lincoln, and recruited conspirators, including Lewis Powell, to help him. Having found no opportunity to abduct the president, on April 14, 1865, Booth assigned Powell to assassinate Seward and George Atzerodt to kill Vice President Johnson. Booth himself would kill Lincoln. The plan was to slay the three senior members of the Executive Branch.

Accordingly, another member of the conspiracy, David Herold, led Powell to the Seward home on horseback and was responsible for holding Powell's horse while he committed the attack. Seward had been hurt in an accident some days before, and Powell gained entry to the home on the excuse he was delivering medicine to the injured man, but was stopped at the top of the stairs by Seward's son Frederick, who insisted Powell give him the medicine. Powell instead attempted to fire on Frederick and beat him over the head with the barrel of his gun when it misfired. Powell burst through the door, threw Fanny Seward (Seward's daughter) to one side, jumped on the bed, and stabbed William Seward in the face and neck five times. A soldier assigned to guard and nurse the secretary, Private George F. Robinson, jumped on Powell, forcing him from the bed.[160] Private Robinson and Augustus Henry Seward, another of Seward's sons, were also injured in their struggle with the would-be assassin. Ultimately, Powell fled, stabbing a messenger, Emerick Hansell, as he went, only to find that Herold, panicked by the screams from the house, had left with both horses. Seward was at first thought dead, but revived enough to instruct Robinson to send for the police and lock the house until they arrived.[161]

Almost simultaneously with the attack on Seward, Booth had mortally wounded Lincoln at Ford's Theatre. Atzerodt, however, decided not to go through with the attack on Johnson. When Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and Navy Secretary Gideon Welles hurried to Seward's home to find out what had happened, they found blood everywhere.[162]

All five men injured that night at the Seward home survived. Powell was captured the next day at the boarding house of Mary Surratt. He was hanged on July 7, 1865, along with Herold, Atzerodt, and Surratt, convicted as conspirators in the Lincoln assassination. Their deaths occurred only weeks after that of Seward's wife Frances, who never recovered from the shock of the assassination attempt.[163]

Johnson administration

Reconstruction and impeachment

In the first months of the new Johnson administration, Seward did not work much with the president. Seward was at first recovering from his injuries, and Johnson was ill for a time in the summer of 1865. Seward was likely in accord with Johnson's relatively gentle terms for the South's re-entry to the Union, and with his pardon of all Confederates but those of high rank. Radical Republicans such as Stanton and Representative Thaddeus Stevens proposed that the freed slaves be given the vote, but Seward was content to leave that to the states (few Northern states gave African-Americans the ballot), believing the priority should be reconciling the power-holding white populations of the North and South to each other.[164]

Unlike Lincoln, who had a close rapport with Seward, Johnson kept his own counsel and generally did not take advantage of Seward's political advice as Congress prepared to meet in December 1865.[165] Johnson had issued proclamations allowing for the southern states to reform their state governments and hold elections; they mostly elected men who had served as prewar or wartime leaders. Seward advised Johnson to state, in his first annual message to Congress, that southern states meet three conditions for readmission to the Union: repeal of secession, repudiation of the war debt incurred by the rebel governments, and ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. Johnson, hoping to appeal to both Republicans and Democrats, did not take the suggestion. Congress did not seat southerners but appointed a joint committee of both houses to make recommendations on the issue. Johnson opposed the committee; Seward was prepared to wait and see.[166]

In early 1866, Congress and president battled over the extension of the authorization of the Freedmen's Bureau. Both sides agreed that the bureau should end after the states were re-admitted, the question was whether that would be soon. With Seward's support, Johnson vetoed the bill. Republicans in Congress were angry with both men, and tried but failed to override Johnson's veto. Johnson vetoed the Civil Rights Bill, which was to grant citizenship to the freedmen. Seward advised a conciliatory veto message; Johnson ignored him, telling Congress it had no right to pass bills affecting the South until it seated the region's congressmen. This time Congress overrode his veto, gaining the necessary two-thirds majority of each house, the first time this had been done on a major piece of legislation in American history.[167]

Johnson hoped the public would elect congressmen who agreed with him in the 1866 midterm elections, and embarked on a trip, dubbed the Swing Around the Circle, giving speeches in a number of cities that summer. Seward was among the officials who went with him. The trip was a disaster for Johnson; he made a number of ill-considered statements about his opponents that were criticized in the press. The Radical Republicans were strengthened by the results of the elections.[168] The Republican anger against Johnson extended to his secretary of state—Senator William P. Fessenden of Maine said of Johnson, "he began by meaning well, but I fear that Seward's evil counsels have carried him beyond the reach of salvation".[169]

In February 1867, both houses of Congress passed the Tenure of Office Bill, purporting to restrict Johnson in the removal of presidential appointees.[170] Johnson suspended, then fired, Stanton over Reconstruction policy differences, leading to the president's impeachment for allegedly violating the Tenure of Office Act. Seward recommended that Johnson hire the renowned attorney, William M. Evarts, and, with Weed, raised funds for the president's successful defense.[171]

Mexico

Mexico was strife-torn in the early 1860s, as it often had been in the fifty years since its independence. There had been 36 changes of government and 73 presidents, and a refusal to pay foreign debts. France, Spain, and Great Britain joined together to intervene in 1861 on the pretext of protecting their nationals, and to secure repayment of debt. Spain and the British soon withdrew, but France remained. Seward realized that a challenge to France at this point might provoke its intervention on the Confederate side, so he stayed quiet. In 1864, French emperor Napoleon III set Archduke Maximilian of Austria on the Mexican throne, with French military support. Seward used strident language publicly but was privately conciliatory toward the French.[172][173][174]

The Confederates had been supportive of France's actions. Upon returning to work after the assassination attempt, Seward warned France that the U.S. still wanted the French gone from Mexico. Napoleon feared that the large, battle-tested American army would be used against his troops. Seward remained conciliatory, and in January 1866, Napoleon agreed to withdraw his troops after a twelve- to eighteen-month period, during which time Maximilian could consolidate his position against the insurgency led by Benito Juárez.[175][176]

In December 1865, Seward bluntly told Napoleon that the United States desired friendship, but, "this policy would be brought into imminent Jeopardy unless France could deem it consistent with her interest and honor to desist from the prosecution of armed intervention in Mexico."[177] Napoleon tried to postpone the French departure, but the Americans had General Phil Sheridan and an experienced combat army on the north bank of the Rio Grande and Seward held firm. Napoleon suggested a new Mexican government that would exclude both Maximilian and Juárez. The Americans had recognized Juárez as the legitimate president and were not willing to consider this. In the meantime, Juárez, with the help of American military aid, was advancing through northeast Mexico. The French withdrew in early 1867. Maximilian stayed behind but was soon captured by Juárez's troops. Although both the U.S. and France urged Juárez against it, the deposed emperor was executed by firing squad on June 19, 1867.[178]

Territorial expansion and Alaska

Although in speeches Seward had predicted all of North America joining the Union, he had, as a senator, opposed the Gadsden Purchase obtaining land from Mexico, and Buchanan's attempts to purchase Cuba from Spain. Those stands were because the land to be secured would become slave territory. After the Civil War, this was no longer an issue, and Seward became an ardent expansionist and even contemplated the purchase of Greenland and Iceland.[179] The Union Navy had been hampered due to the lack of overseas bases during the war, and Seward also believed that American trade would be helped by the purchase of overseas territory.[180]

Believing, along with Lincoln, that the U.S. needed a naval base in the Caribbean, in January 1865, Seward offered to purchase the Danish West Indies (today the United States Virgin Islands). Late that year, Seward sailed for the Caribbean on a naval vessel. Among the ports of call was St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies, where Seward admired the large, easily defended harbor. Another stop was in the Dominican Republic, where he opened talks to obtain Samaná Bay. When Congress reconvened in December 1866, Seward caused a sensation by entering the chamber of the House of Representatives and sitting down with the administration's enemy, Congressman Stevens, persuading him to support an appropriation for more money to expedite the purchase of Samaná, and sent his son Frederick to the Dominican Republic to negotiate a treaty. Both attempts fell through; the Senate, in the dying days of the Johnson administration, failed to ratify a treaty for the purchase of the Danish possessions, while negotiations with the Dominican Republic were not successful.[181][182]

Seward had been interested in whaling as a senator; his interest in Russian America was a byproduct of this. In his speech prior to the 1860 convention, he predicted the territory would become part of the U.S., and when he learned in 1864 that it might be for sale, he pressed the Russians for negotiations. Russian minister Baron Eduard de Stoeckl recommended the sale.[183] The territory was a money loser, and the Russian-American Company itself allowed its charter to expire in 1861. Russia could use the money more efficiently for its expansion in Siberia or Central Asia. Keeping it ran the risk of it being captured in war by the British, or overrun by American settlers. Stoeckl was given the authority to make the sale and when he returned in March 1867, negotiated with the Secretary of State. Seward initially offered $5 million; the two men settled on $7 million and on March 15, Seward presented a draft treaty to the Cabinet. Stoeckl's superiors raised several concerns; to induce him to waive them, the final purchase price was increased to $7.2 million. The treaty was signed in the early morning of March 30, 1867, and ratified by the Senate on April 10. Stevens sent the secretary a note of congratulations, predicting that the Alaska Purchase would be seen as one of Seward's greatest accomplishments.[lower-alpha 3][184][185]

1868 election, retirement and death

Seward hoped that Johnson would be nominated at the 1868 Democratic National Convention, but the delegates chose former New York governor Horatio Seymour. The Republicans chose General Ulysses S. Grant, who had a hostile relationship with Johnson. Seward gave a major speech on the eve of the election, endorsing Grant, who was easily elected. Seward met twice with Grant after the election, leading to speculation that he was seeking to remain as secretary for a third presidential term. However, the president-elect had no interest in retaining Seward, and the secretary resigned himself to retirement. Grant refused to have anything to do with Johnson, even declining to ride to his inauguration in the same carriage as the outgoing president, as was customary. Despite Seward's attempts to persuade him to attend Grant's swearing-in, Johnson and his Cabinet spent the morning of March 4, 1869, at the White House dealing with last-minute business, then left once the time for Grant to be sworn in had passed. Seward returned to Auburn.[186]

Restless in Auburn, Seward embarked on a trip across North America by the new transcontinental railroad. In Salt Lake City, Utah Territory, he met with Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who had worked as a carpenter on Seward's house (then belonging to Judge Miller) as a young man. On reaching the Pacific Coast, the Seward party sailed north on the steamer Active[187] to visit Sitka, Department of Alaska, part of the vast wilderness Seward had acquired for the U.S. After spending time in Oregon and California, the party went to Mexico, where he was given a hero's welcome. After a visit to Cuba, he returned to the U.S.,[188] concluding his nine-month trip in March 1870.[189]

In August 1870, Seward embarked on another trip, this time westbound around the world. With him was Olive Risley, daughter of a Treasury Department official, to whom he became close in his final year in Washington. They visited Japan, then China, where they walked on the Great Wall. During the trip, they decided that Seward would adopt Olive, and he did so, thus putting an end to gossip and the fears of his sons that Seward would remarry late in life. They spent three months in India, then journeyed through the Middle East and Europe, not returning to Auburn until October 1871.[190]

Back in Auburn, Seward began his memoirs, but only reached his thirties before putting it aside to write of his travels.[lower-alpha 4] In these months he was steadily growing weaker. On October 10, 1872, he worked at his desk in the morning as usual, then complained of trouble breathing. Seward grew worse during the day, as his family gathered around him. Asked if he had any final words, he said, "Love one another".[191] Seward died that afternoon. His funeral a few days later was preceded by the people of Auburn and nearby filing past his open casket for four hours. Thurlow Weed was there for the burial of his friend, and Harriet Tubman, a former slave whom the Sewards had aided, sent flowers. President Grant sent his regrets he could not be there.[192][193] William Seward rests with his wife Frances and daughter Fanny (1844–1866), in Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn.[192][193]

Legacy and historical view

.jpg.webp)

Seward's reputation, controversial in life, remained so in death, dividing his contemporaries. Former navy secretary Gideon Welles argued that not only did Seward lack principles, Welles was unable to understand how Seward had fooled Lincoln into thinking that he did, gaining entry to the Cabinet thereby.[194] Charles Francis Adams, minister in London during Seward's tenure as secretary, deemed him "more of a politician than a statesman", but Charles Anderson Dana, former Assistant Secretary of War, disagreed, writing that Seward had "the most cultivated and comprehensive intellect in the administration" and "what is very rare in a lawyer, a politician, or a statesman—imagination".[195]