George Henry Thomas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | "Rock of Chickamauga," "Sledge of Nashville," "Slow Trot Thomas," "Old Slow Trot," "Pap" |

| Born | July 31, 1816 Newsom's Depot, Virginia, US |

| Died | March 28, 1870 (aged 53) San Francisco, California, US |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | United States Army (Union Army) |

| Years of service | 1840–1870 |

| Rank | Major general |

| Commands held | XIV Corps Army of the Cumberland Military Division of the Pacific |

| Battles/wars | |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Lucretia Kellogg, m. 1852 |

| Signature | |

George Henry Thomas (July 31, 1816 – March 28, 1870) was an American general in the Union Army during the American Civil War and one of the principal commanders in the Western Theater.

Thomas served in the Mexican–American War and later chose to remain with the U.S. Army for the Civil War as a Southern Unionist, despite his heritage as a Virginian (whose home state would join the Confederate States of America). He won one of the first Union victories in the war, at Mill Springs in Kentucky, and served in important subordinate commands at Perryville and Stones River. His stout defense at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863 saved the Union Army from being completely routed, earning him his most famous nickname, "the Rock of Chickamauga." He followed soon after with a dramatic breakthrough on Missionary Ridge in the Battle of Chattanooga. In the Franklin–Nashville Campaign of 1864, he achieved one of the most decisive victories of the war, destroying the army of Confederate General John Bell Hood, his former student at West Point, at the Battle of Nashville.

Thomas had a successful record in the Civil War, but he failed to achieve the historical acclaim of some of his contemporaries, such as Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman. He developed a reputation as a slow, deliberate general. In an environment rife with jealousy and avarice for promotion and recognition, Thomas stood out as an oddball for occasionally refusing promotions to positions that he thought he were still not capable of; although on some occasions he regretted his refusals or found it injurious that he was passed over for promotion. After the war, he did not write memoirs to advance his legacy.

Early life and education

Thomas was born at Newsom's Depot, Southampton County, Virginia, five miles (8 km) from the North Carolina border.[1] His father, John Thomas, of Welsh[2] descent, and his mother, Elizabeth Rochelle Thomas, a descendant of French Huguenot immigrants, had six children. George had three sisters and two brothers.[3] The family led an upper-class plantation lifestyle. By 1829, they owned 685 acres (2.77 km2) and 15 slaves. John died in a farm accident when George was 13, leaving the family in financial difficulties.[4] George Thomas, his sisters, and his widowed mother were forced to flee from their home and hide in the nearby woods during Nat Turner's 1831 slave rebellion.[5] Benson Bobrick has suggested that while some repressive acts were enforced following the crushing of the revolt, Thomas took the lesson another way, seeing that slavery was so vile an institution that it had forced the slaves to act in violence. This was a major event in the formation of his views on slavery; that the idea of the contented slave in the care of a benevolent overlord was a sentimental myth.[6] Christopher Einolf, in contrast wrote "For George Thomas, the view that slavery was needed as a way of controlling blacks was supported by his personal experience of Nat Turner's Rebellion. ... Thomas left no written record of his opinion on slavery, but the fact that he owned slaves during much of his life indicates that he was not opposed to it."[7] A traditional story is that Thomas taught as many as 15 of his family's slaves to read, violating a Virginia law that prohibited this,[8] and despite the wishes of his father.[9]

Thomas was appointed to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1836 by Congressman John Y. Mason, who warned Thomas that no nominee from his district had ever graduated successfully. Entering at age 20, Thomas was known to his fellow cadets as "Old Tom," and he became instant friends with his roommates, William T. Sherman and Stewart Van Vliet. He made steady academic progress, was appointed a cadet officer in his second year, and graduated 12th in a class of 42 in 1840.[10] He was appointed a second lieutenant in Company D, 3rd U.S. Artillery.[11]

Antebellum military career

Thomas's first assignment with his artillery regiment began in late 1840 at the primitive outpost of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in the Seminole Wars, where his troops performed infantry duty. He led them in successful patrols and was appointed a brevet first lieutenant on November 6, 1841.[12] From 1842 until 1845, he served in posts at New Orleans, Fort Moultrie in Charleston Harbor, and Fort McHenry in Baltimore. With the Mexican–American War looming, his regiment was ordered to Texas in June 1845.[13]

In Mexico, Thomas led a gun crew with distinction at the battles of Fort Brown, Resaca de la Palma, Monterrey, and Buena Vista, receiving two more brevet promotions.[14] At Buena Vista, Gen. Zachary Taylor reported that "the services of the light artillery, always conspicuous, were more than unusually distinguished" during the battle. Brig. Gen. John E. Wool wrote about Thomas and another officer that "without our artillery we would not have maintained our position a single hour." Thomas's battery commander wrote that Thomas's "coolness and firmness contributed not a little to the success of the day. Lieutenant Thomas more than sustained the reputation he has long enjoyed in his regiment as an accurate and scientific artillerist."[15] During the war, Thomas served closely with an artillery officer who would be a principal antagonist in the Civil War—Captain Braxton Bragg.[16]

Thomas was reassigned to Florida in 1849–50. In 1851, he returned to West Point as a cavalry and artillery instructor, where he established a close professional and personal relationship with another Virginia officer, Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee, the Academy superintendent. His appointment there was based in part on a recommendation from Braxton Bragg. Concerned about the poor condition of the Academy's elderly horses, Thomas moderated the tendency of cadets to overwork them during cavalry drills and became known as "Slow Trot Thomas". Two of Thomas's students who received his recommendation for assignment to the cavalry, J.E.B. Stuart and Fitzhugh Lee, became prominent Confederate cavalry generals. Another Civil War connection was a cadet expelled for disciplinary reasons on Thomas's recommendation, John Schofield, who would excoriate Thomas in postbellum writings about his service as a corps commander under Thomas in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign. On November 17, 1852, Thomas married Frances Lucretia Kellogg, age 31, from Troy, New York. The couple remained at West Point until 1854. Thomas was promoted to captain on December 24, 1853.[17]

In the spring of 1854, Thomas's artillery regiment was transferred to California and he led two companies to San Francisco via the Isthmus of Panama, and then on a grueling overland march to Fort Yuma. On May 12, 1855, Thomas was appointed a major of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry (later re-designated the 5th U.S. Cavalry) by Jefferson Davis, then Secretary of War. Once again, Braxton Bragg had provided a recommendation for Thomas's advancement. There was a suspicion as the Civil War drew closer that Davis had been assembling and training a combat unit of elite U.S. Army officers who harbored Southern sympathies, and Thomas's appointment to this regiment implied that his colleagues assumed he would support his native state of Virginia in a future conflict.[18] Thomas resumed his close ties with the second-in-command of the regiment, Robert E. Lee, and the two officers traveled extensively together on detached service for court-martial duty. In October 1857, Major Thomas assumed acting command of the cavalry regiment, an assignment he would retain for 2½ years. On August 26, 1860, during a clash with a Comanche warrior, Thomas was wounded by an arrow passing through the flesh near his chin area and sticking into his chest at Clear Fork, Brazos River, Texas. Thomas pulled the arrow out and, after a surgeon dressed the wound, continued to lead the expedition. This was the only combat wound that Thomas suffered throughout his long military career.[19]

In November 1860, Thomas requested a one-year leave of absence. His antebellum career had been distinguished and productive, and he was one of the rare officers with field experience in all three combat arms—infantry, cavalry, and artillery. On his way home to southern Virginia, he suffered a mishap in Lynchburg, Virginia, falling from a train platform and severely injuring his back. This accident led him to contemplate leaving military service and caused him pain for the rest of his life. Continuing to New York to visit with his wife's family, Thomas stopped in Washington, D.C., and conferred with general-in-chief Winfield Scott, advising Scott that Maj. Gen. David E. Twiggs, the commander of the Department of Texas, harbored secessionist sympathies and could not be trusted in his post.[20] Twiggs did indeed surrender his entire command to Confederate authorities shortly after Texas seceded, and later served in the Confederate military.[21]

American Civil War

Remaining with the Union

At the outbreak of the Civil War, 19 of the 36 officers in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry resigned, including three of Thomas's superiors—Albert Sidney Johnston, Robert E. Lee, and William J. Hardee.[22] Many Southern-born officers were torn between loyalty to their states and loyalty to their country. Thomas struggled with the decision but opted to remain with the United States. His Northern-born wife probably helped influence his decision. In response, his family turned his picture against the wall, destroyed his letters, and never spoke to him again. During the economic hard times in the South after the war, Thomas sent some money to his sisters, who angrily refused to accept it, declaring they had no brother.[23]

Nevertheless, Thomas stayed in the Union Army with some degree of suspicion surrounding him, despite his action concerning Twiggs. On January 18, 1861, a few months before Fort Sumter, he had applied for a job as the commandant of cadets at the Virginia Military Institute.[24] Any real tendency to the secessionist cause, however, could be refuted when he turned down Virginia Governor John Letcher's offer to become chief of ordnance for the Virginia Provisional Army.[25] On June 18, his former student and fellow Virginian, Confederate Col. J.E.B. Stuart, wrote to his wife, "Old George H. Thomas is in command of the cavalry of the enemy. I would like to hang, hang him as a traitor to his native state."[26] Nevertheless, as the Civil War carried on, he won the affection of Union soldiers serving under him as a "soldier's soldier", who took to affectionately referring to Thomas as "Pap Thomas".[27]

Kentucky

Thomas was promoted in rapid succession to be lieutenant colonel (on April 25, 1861, replacing Robert E. Lee) and colonel (May 3, replacing Albert Sidney Johnston) in the regular army, and brigadier general of volunteers (August 17).[28] In the First Bull Run Campaign, he commanded a brigade under Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson in the Shenandoah Valley,[29] but all of his subsequent assignments were in the Western Theater. Reporting to Maj. Gen. Robert Anderson in Kentucky, Thomas was assigned to training recruits and to command an independent force in the eastern half of the state. On January 18, 1862, he defeated Confederate Brig. Gens. George B. Crittenden and Felix Zollicoffer at Mill Springs, gaining the first important Union victory in the war, breaking Confederate strength in eastern Kentucky, and lifting Union morale.[30]

Shiloh and Corinth

On December 2, 1861, Brig. Gen. Thomas was assigned to command the 1st Division of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell's Army of the Ohio. He missed the Battle of Shiloh (April 7, 1862), arriving after the fighting had ceased. The victor at Shiloh, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, came under severe criticism for the bloody battle due to the surprise and lack of preparations and his superior, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, reorganized his Department of the Mississippi to ease Grant out of direct field command. The three armies in the department were divided and recombined into three "wings". Thomas, promoted to major general effective April 25, 1862, was given command of the Right Wing, consisting of four divisions from Grant's former Army of the Tennessee and one from the Army of the Ohio. Thomas successfully led this force in the siege of Corinth. On June 10, Grant returned to command of the original Army of the Tennessee.

Perryville, Stones River, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga

Thomas resumed service under Don Carlos Buell. During Confederate General Braxton Bragg's invasion of Kentucky in the fall of 1862, the Union high command became nervous about Buell's cautious tendencies and offered command of the Army of the Ohio to Thomas, who refused, as Buell's plans were too far advanced. Thomas served as Buell's second-in-command at the Battle of Perryville, but his wing of the army did not hear the fighting engaged in by the other flank. Although tactically inconclusive, the battle halted Bragg's invasion of Kentucky as he voluntarily withdrew to Tennessee. Again frustrated with Buell's ineffective pursuit of Bragg, the government replaced him with Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans. Thomas wrote on October 30, 1862, a letter of protest to Secretary Stanton, because Rosecrans had been junior to him, but Stanton wrote back on November 15, telling him that this was not the case (Rosecrans had in fact been his junior, but his commission as major general had been backdated to make him senior to Thomas) and reminding him of his earlier refusal to accept command; Thomas demurred and withdrew his protest.[31]

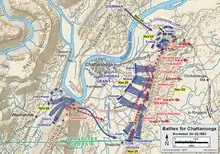

Fighting under Rosecrans, commanding the "Center" wing of the newly renamed Army of the Cumberland, Thomas gave an impressive performance at the Battle of Stones River, holding the center of the retreating Union line and once again preventing a victory by Bragg. He was in charge of the most important part of the maneuvering from Decherd to Chattanooga during the Tullahoma Campaign (June 22 – July 3, 1863) and the crossing of the Tennessee River. At the Battle of Chickamauga on September 19, 1863, now commanding the XIV Corps, he once again held a desperate position against Bragg's onslaught while the Union line on his right collapsed. Thomas rallied broken and scattered units together on Horseshoe Ridge to prevent a significant Union defeat from becoming a hopeless rout. Future president James Garfield, a field officer for the Army of the Cumberland, visited Thomas during the battle, carrying orders from Rosecrans to retreat; when Thomas said he would have to stay behind to ensure the Army's safety, Garfield told Rosecrans that Thomas was "standing like a rock." After the battle he became widely known by the nickname "The Rock of Chickamauga", representing his determination to hold a vital position against strong odds.[32]

_-_NARA_-_530349.jpg.webp)

Thomas succeeded Rosecrans in command of the Army of the Cumberland shortly before the Battles for Chattanooga (November 23–25, 1863), a stunning Union victory that was highlighted by Thomas's troops taking Lookout Mountain on the right and then storming the Confederate line on Missionary Ridge, the next day. When the Army of the Cumberland advanced further than ordered, General Grant, on Orchard Knob asked Thomas, "Who ordered the advance?" Thomas replied, "I don't know. I did not."

Atlanta and Franklin/Nashville

During Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman's advance towards Georgia with three armies in the spring of 1864, the Army of the Cumberland numbered over 60,000 men, and Thomas's staff did the logistics and engineering for Sherman's entire army group, including developing a novel series of Cumberland pontoons. At the chaotic Battle of Peachtree Creek (July 20, 1864), Thomas's troops defended against an attack by Lt. Gen. John B. Hood's army in its first attempt to break the siege of Atlanta.

When Hood broke away from Atlanta in the autumn of 1864, he menaced Sherman's long line of communications, and endeavored to force Sherman to follow him, Sherman abandoned his communications and embarked on an offensive through Georgia. Thomas was ordered to defend Tennessee from confederate offensive operations, culminating in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign. As Hood's army of Tennessee entered the state, Thomas hurriedly attempted to concentrate his forces. He had a numerical advantage, but he still wished for his entire force to be concentrated. He ordered the Army of the Ohio under command of his subordinate general Schofield to delay the confederates as much as possible. Schofield's small, single-corps army attempted to harangue the confederate crossing of the Tennessee, but Hood's army executed a skillful manoeuvre and emplaced themselves behind Schofield's corps, on a hill named Spring Hill. In the ensuing fighting, Schofield's army came near destruction, but due to a series of miscommunications Hood's army was frozen for a day as the Army of the Ohio beat a hurried retreat in front of it, and defeated confederate cavalry led by Gen. Forrest in a rearguard action. This army made a forced march to Franklin where it entrenched itself strongly.[33]

At the Battle of Franklin on November 30, 1864, the smallest part of Thomas's force, under command of Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield, resisted an attack by Hood's army and held him in check for a day as pontoons were built over the Harpeth river (bridges had been destroyed), Schofield's army retreated the same night and made a desperate forced march for Nashville, where all union forces in Tennessee were being concentrated. Thomas had to organize his forces, which had been drawn from all parts of the West and which included many raw troops and even quartermaster employees. Hood's army subsequently arrived, found the vastly larger union army heavily entrenched, and began entrenching in preparation for a siege of Nashville. Grant (General in Chief of all union armies) ordered Thomas to attack, and Thomas replied that he needed a few days to have everything in order for an attack. Grant had grown greatly exasperated and nervous at the prospect of a confederate invasion through Tennessee and Kentucky, which could turn the tide of the war, him and Halleck both bombarded Thomas daily with frequent communiques ordering him to attack the confederate army. As Thomas' preparations ended, a snow storm immobilized both armies entirely for four days, as snow melted Thomas sent a message to Grant and the war department that as snow melted, he would attack the next day. Grant had grown completely impatient with Thomas during this period and drafted an order relieving him from command. Halleck had wired Thomas that Grant was deeply unhappy with Thomas' performance, and Thomas replied that if he wished to relieve him from command he would 'submit without a murmur'. General Grant grew impatient at the continued delay, and finally sent Maj. Gen. John A. Logan with an order to replace Thomas as commander, and soon afterwards Grant started a journey west from City Point, Virginia to take command in person.[34]

.tif.jpg.webp)

As the weather finally warmed and rain washed away the snow on December 14,Thomas drafted the orders and distributed them to his corps commanders on the day to attack on the confederates on the next day, and the Battle of Nashville effectively destroyed Hood's army in two days of fighting. Thomas sent his wife, Frances Lucretia Kellogg Thomas, the following telegram, the only communication surviving of the Thomases' correspondence: "We have whipped the enemy, taken many prisoners and considerable artillery."

As news of the victory streamed north, Logan returned to Grant and returned his orders to relieve Thomas. Thomas was appointed a major general in the regular army, with date of rank of his Nashville victory, and received the Thanks of Congress:[35]

... to Major-General George H. Thomas and the officers and soldiers under his command for their skill and dauntless courage, by which the rebel army under General Hood was signally defeated and driven from the state of Tennessee.

Thomas may have resented his delayed promotion to major general (which made him junior by date of rank to Sheridan); upon receiving the telegram announcing it, he remarked to Surgeon George Cooper: "I suppose it is better late than never, but it is too late to be appreciated. I earned this at Chickamauga.".[36]

Thomas also received another nickname from his victory: "The Sledge of Nashville".[37]

Later life and death

After the end of the Civil War, Thomas commanded the Department of the Cumberland in Kentucky and Tennessee, and at times also West Virginia and parts of Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama, through 1869. During the Reconstruction period, Thomas acted to protect freedmen from white abuses. He set up military commissions to enforce labor contracts since the local courts had either ceased to operate or were biased against blacks. Thomas also used troops to protect places threatened by violence from the Ku Klux Klan.[38] In a November 1868 report, Thomas noted efforts made by former Confederates to paint the Confederacy in a positive light, stating:

[T]he greatest efforts made by the defeated insurgents since the close of the war have been to promulgate the idea that the cause of liberty, justice, humanity, equality, and all the calendar of the virtues of freedom, suffered violence and wrong when the effort for southern independence failed. This is, of course, intended as a species of political cant, whereby the crime of treason might be covered with a counterfeit varnish of patriotism, so that the precipitators of the rebellion might go down in history hand in hand with the defenders of the government, thus wiping out with their own hands their own stains; a species of self-forgiveness amazing in its effrontery, when it is considered that life and property—justly forfeited by the laws of the country, of war, and of nations, through the magnanimity of the government and people—was not exacted from them.

— George Henry Thomas, November 1868.[39]

President Andrew Johnson offered Thomas the rank of lieutenant general—with the intent to eventually replace Grant, a Republican and future president, with Thomas as general in chief—but the ever-loyal Thomas asked the Senate to withdraw his name for that nomination because he did not want to be party to politics. In 1869 he requested assignment to command the Military Division of the Pacific with headquarters at the Presidio of San Francisco. He died there of a stroke on March 28, 1870, while writing an answer to an article criticizing his military career by his wartime rival John Schofield.[35] Sherman, by then general-in-chief, personally conveyed the news to President Grant at the White House. None of Thomas's blood relatives attended his funeral as they had never forgiven him for his loyalty to the Union. He was buried in Oakwood Cemetery, in Troy, New York. His gravestone was sculpted by Robert E. Launitz and comprises a white marble sarcophagus topped by a bald eagle.[40]

Legacy

The veterans' organization for the Army of the Cumberland, throughout its existence, fought to see that he was honored for all he had done. In 1879, they commissioned the equestrian statue of Thomas at Thomas Circle, Washington, D.C.[41]

Thomas was in chief command of only two battles in the Civil War, the Battle of Mill Springs at the beginning and the Battle of Nashville near the end. Both were decisive victories. However, his contributions at the battles of Stones River, Chickamauga, Chattanooga, and Peachtree Creek were decisive. His main legacies lay in his development of modern battlefield doctrine and in his mastery of logistics.

Thomas has generally been held in high esteem by Civil War historians; Bruce Catton and Carl Sandburg wrote glowingly of him, and many consider Thomas one of the top three Union generals of the war, after Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman. But Thomas never entered the popular consciousness like those men. The general destroyed his private papers, saying he did not want "his life hawked in print for the eyes of the curious." Beginning in the 1870s, many Civil War generals published memoirs, justifying their decisions or re-fighting old battles, but Thomas, who died in 1870, did not publish his own memoirs. In addition, most of his campaigns were in the Western theater of the war, which received less attention both in the press of the day and in contemporary historical accounts.

Grant and Thomas also had a cool relationship, for reasons that are not entirely clear, but are well-attested by contemporaries. It apparently started when Halleck placed Thomas in command of most of Grant's divisions after the Battle of Shiloh. When a rain-soaked Grant arrived at Thomas's headquarters before the Chattanooga Campaign, Thomas, caught up in other activity, did not provide dry clothes for several minutes until Grant's staffer intervened. Thomas's perceived slowness at Nashville—although necessitated by the weather—drove Grant into a fit of impatience, and Grant nearly replaced Thomas. In his Personal Memoirs, Grant minimized Thomas's contributions, particularly during the Franklin-Nashville Campaign, saying his movements were "always so deliberate and so slow, though effective in defence."[42]

Grant did, however, acknowledge that Thomas's eventual success at Nashville obviated all criticism. Sherman, who had been close to Thomas throughout the war, also repeated the accusation after the war that Thomas was "slow", and this damning with faint praise tended to affect perceptions of the Rock of Chickamauga up to the present day. Both Sherman and Grant attended Thomas's funeral, and were reported by third parties to have been visibly moved by his passing. Thomas's legendary bay horse, Billy, bore his friend Sherman's name.

Thomas was always on good terms with his commanding officer in the Army of the Cumberland, William Rosecrans. Even after Rosecrans was relieved of command by Grant and replaced by Thomas, he had nothing but praise for him. Upon hearing of Thomas' death, Rosecrans sent a letter to the National Tribune, stating Thomas' passing was a "National Calamity... Few knew him better than I did, none valued him more."[43]

In 1887, Sherman published an article praising Grant and Thomas, and contrasting them to Robert E. Lee. After noting that Thomas, unlike his fellow Virginian Lee, stood by the Union, Sherman wrote:

During the whole war his services were transcendent, winning the first substantial victory at Mill Springs in Kentucky, January 20th, 1862, participating in all the campaigns of the West in 1862-3-4, and finally, December 16th, 1864 annihilating the army of Hood, which in mid winter had advanced to Nashville to besiege him.[44]

Sherman concluded that Grant and Thomas were "heroes" deserving "monuments like those of Nelson and Wellington in London, well worthy to stand side by side with the one which now graces our capitol city of 'George Washington.'"[45]

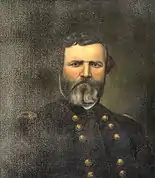

J. C. Buttre's 1877 engraving of Thomas, based on a photograph by George N. Bernard[46]

J. C. Buttre's 1877 engraving of Thomas, based on a photograph by George N. Bernard[46].jpg.webp) Woodcut by Thomas Nast

Woodcut by Thomas Nast General George H. Thomas' life-size statue by sculptor Rodolfo Ayoroa, located at Civil War Park, Lebanon, Kentucky

General George H. Thomas' life-size statue by sculptor Rodolfo Ayoroa, located at Civil War Park, Lebanon, Kentucky The bronze equestrian statue of Thomas by John Quincy Adams Ward, located at Thomas Circle in Washington, D.C.

The bronze equestrian statue of Thomas by John Quincy Adams Ward, located at Thomas Circle in Washington, D.C. Painting of Thomas at Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park

Painting of Thomas at Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park

In memoriam

A fort south of Newport, Kentucky was named in his honor, and the city of Fort Thomas now stands there and carries his name as well. A memorial honoring Thomas, Major General George Henry Thomas, can be found in the eponymous Thomas Circle in Washington, D.C.[47]

A distinctive engraved portrait of Thomas appeared on U.S. paper money in 1890 and 1891. The bills are called "treasury notes" or "coin notes" and are widely collected today because of their fine, detailed engraving. The $5 Thomas "fancyback" note of 1890, with an estimated 450–600 in existence relative to the 7.2 million printed, ranks as number 90 in the "100 Greatest American Currency Notes" compiled by Bowers and Sundman (2006).[48]

Thomas County, Kansas, established in 1888, is named in his honor. The townships of Thomas County are named after fallen soldiers in the Battle of Chickamauga.[49] Thomas County, Nebraska, is also named after him.[50]

In 1999 a statue of Thomas by sculptor Rudy Ayoroa was unveiled in Lebanon, Kentucky.[51]

A bust of Thomas is located in Grant's Tomb in Manhattan, New York.

Thomas's torn loyalties during the Civil War are briefly discussed in Chapter XIX of MacKinlay Kantor's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel "Andersonville" (1955).

A three-quarter length portrait of him, executed by U.S. general Samuel Woodson Price (1828–1918) in 1869 and gifted by the heirs of General Price, hangs in the stairwell to Special Collections at Transylvania University, Lexington, Kentucky.

A Sons of Union Veterans Camp, Camp No. 19 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, is named in his honor.

He was honored as the namesake of the George Henry Thomas Post Number 5 of the Grand Army of the Republic.[52] A 10-mile road in Southampton County, Virginia, his birthplace, is named General Thomas Highway.

See also

Citations

- ↑ Cleaves, p. 7.

- ↑ Coppee, LL. D., Henry (1898). Great Commanders, General Thomas. D. Appleton and Company. p. 2.

- ↑ Coppee, LL. D., Henry (1898). Great Commanders, General Thomas. D. Appleton and Company. p. 3.

- ↑ Einolf, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Cleaves, pp. 6–7; Einolf, p. 20; O'Connor, p. 60.

- ↑ Bobrick, p. 14.

- ↑ Einolf, p. 19. Einolf's statement about owning slaves "during much of his life" is apparently derived from his family's ownership, his use of a family slave as a personal valet during "at least part of his military service", and the woman named Ellen whom his wife Francis bought in 1858 (p. 74).

- ↑ Cleaves, pp. 6–7; O'Connor, p. 60; Furgurson, p. 57, suggests that while this was illegal, it was not uncommon for slaves to be taught to read; biography of Thomas Archived November 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, by Kennedy Hickman. Einolf, p. 13, offers a contrary view: "It is unlikely, however, that Thomas taught his family's slaves how to read.... While Thomas did eventually come to support education and freedom for blacks, he did not do so until much later in life, when the events of the Civil War had changed his views on race." He attributes (p. 12) the story to an interview conducted in 1890 by Oliver Otis Howard, who "wanted to explain Thomas's Unionism in terms of an antipathy toward slavery and so looked for early indications of sympathy toward African-Americans in Thomas's childhood."

- ↑ Coppée, p. 4.

- ↑ Einolf, pp. 22–29.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 527; Einolf, p. 30.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 527; Einolf, pp. 32–35.

- ↑ Einolf, pp. 36–40.

- ↑ Einolf, p. 55, and Cleaves, p. 43, refer to three brevet promotions. Eicher, p. 527, documents only two: brevet captain for Monterrey and brevet major for Buena Vista. Van Horne, p. 7, also lists only the two promotions.

- ↑ Einolf, p. 54.

- ↑ Cleaves, pp. 24–42; Einolf, pp. 39–57.

- ↑ Cleaves, pp. 48–51; Einolf, pp. 60–66; Eicher, p. 527. Cleaves claims that Thomas was assigned to the Academy in 1853 on the recommendation of William S. Rosecrans.

- ↑ Einolf, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Einolf, pp. 72–79; Cleaves, pp. 56–61.

- ↑ Einolf, pp. 78–81; Cleaves, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Cutrer, Thomas W.; Smith, David Paul. "TSHA | Twiggs, David Emanuel". www.tshaonline.org. Austin, TX: Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ↑ Einolf, pp. 93, 97.

- ↑ Einolf, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Einolf, p. 81.

- ↑ Einolf, p. 83; Cleaves, pp. 64–66.

- ↑ Einolf, p. 99.

- ↑ Civil War letters by Sargeant Sherman Leland, 104th Illinois Infantry, Co.D., a unit which served under General Thomas during the Chattanooga Campaign. Mr. Leland noted this is the nickname fellow soldiers used to convey genuine respect and affection for the General. They also referred to General Sherman as "Uncle Billy" These letters are unpublished.

- ↑ Einolf, pp. 97, 101; Eicher, p. 527.

- ↑ Einolf, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Einolf, pp. 101–23; Cleaves, pp. 81–100.

- ↑ Broadwater, p. 88-91

- ↑ Broadwater, p. 136.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911, p. 866.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911, pp. 866–867.

- 1 2 Chisholm 1911, p. 867.

- ↑ Stephen Z. Starr, "Grant and Thomas: December, 1864," Archived November 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Cincinnati Civil War Round Table website

- ↑ Broadwater, p. 1, pp. 205-221.

- ↑ Einolf, Christopher J.: "Forgotten Heroism", North & South, Volume 11, number 2, page 90, December 2008.

- ↑ Thomas, George Henry (December 4, 1868). "The Department Reports". Sacramento Daily Union. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

[T]he greatest efforts made by the defeated insurgents since the close of the war have been to promulgate the idea that the cause of liberty, justice, humanity, equality, and all the calendar of the virtues of freedom, suffered violence and wrong when the effort for southern independence failed. This is, of course, intended as a species of political cant, whereby the crime of treason might be covered with a counterfeit varnish of patriotism, so that the precipitators of the rebellion might go down in history hand in hand with the defenders of the government, thus wiping out with their own hands their own stains; a species of self-forgiveness amazing in its effrontery, when it is considered that life and property—justly forfeited by the laws of the country, of war, and of nations, through the magnanimity of the government and people—was not exacted from them.

- ↑ Harrison, A. Rebecca (August 3, 1984). "National Register of Historic Places Registration nomination, Oakwood Cemetery (Javascript)". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. p. 11. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ↑ Furgurson, Ernest B. (March 1, 2007). "Catching Up With "Old Slow Trot"". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ↑ Grant, chapter LX.

- ↑ Cozzens, Peter (1992). This Terrible Sound. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01703-X.

- ↑ Sherman, W. T. (May 1887). "Grant, Thomas, Lee" (PDF). North American Review. 144 (366): 437–450. JSTOR 25101219., pp. 445.

- ↑ Sherman, W. T. (May 1887). "Grant, Thomas, Lee". North American Review. 144 (366): 437–450.

- ↑ Cleaves, p. 277.

- ↑ dcmemorials.com

- ↑ Bowers, Q.D., and D.M. Sundman, 100 Greatest American Currency Notes, Atlanta: Whitman Publishing, 2006.

- ↑ Thomas County website Archived August 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, Lilian Linder (1925). "Nebraska Place-Names". p. 139. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Announcement of Lebanon sculpture". Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved September 19, 2010.

- ↑ Together We Served.com, Essay

General references

- Bobrick, Benson. Master of War: The Life of General George H. Thomas. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7432-9025-8.

- Broadwater, Robert. General George H. Thomas. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7864-3856-3.

- Bowers, Q.D., and D.M. Sundman, 100 Greatest American Currency Notes, Atlanta: Whitman Publishing, 2006.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Thomas, George Henry". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 866–867.

- Cleaves, Freeman. Rock of Chickamauga: The Life of General George H. Thomas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1948. ISBN 0-8061-1978-0.

- Coppée, Henry. General Thomas, The Great Commanders Series. New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1893. OCLC 2146008.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Einolf, Christopher J. George Thomas: Virginian for the Union. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8061-3867-1.

- Furgurson, Ernest B. "Catching up with Old Slow Trot". Smithsonian, March 2007.

- Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. 2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. ISBN 0-914427-67-9.

- O'Connor, Richard. Thomas, Rock of Chickamauga. New York: Prentice-Hall, 1948. OCLC 1345107.

- Van Horne, Thomas Budd. The Life of Major-General George H. Thomas. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1882. OCLC 458382436.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

Further reading

- Cimprich, John. "A Critical Moment and Its Aftermath for George H. Thomas." in The Moment of Decision: Biographical Essays on American Character and Regional Identity. Randall M. Miller and John R. McKivigan, editors. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1994.

- Downing, David C. A South Divided: Portraits of Dissent in the Confederacy. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House, 2007. ISBN 978-1-58182-587-9.

- Johnson, Richard W. Memoir of Maj-Gen George H. Thomas. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott and Co., 1881. OCLC 812607.

- McKinney, Francis F. Education in Violence: The Life of George H. Thomas and the History of the Army of the Cumberland. Chicago: Americana House, 1991. ISBN 0-9625290-5-2.

- Palumbo, Frank A. George Henry Thomas, Major General, U.S.A.: The Dependable General, Supreme in Tactics of Strategy and Command. Dayton, OH: Morningside Bookshop, 1983. ISBN 0-89029-311-2.

- Thomas, Wilbur D. General George H. Thomas: The Indomitable Warrior. New York: Exposition Press, 1964. OCLC 1655500.

- Van Horne, Thomas B. The Army of the Cumberland: Its Organizations, Campaigns, and Battles. New York: Smithmark Publishers, 1996. ISBN 0-8317-5621-7. First published 1885 by Robert Clarke & Co.

- Wills, Brian Steel. George Henry Thomas: As True as Steel. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012. ISBN 978-0-7006-1841-5.

External links

- George H. Thomas in Encyclopedia Virginia

- Stone, Henry (1889). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography.

- Johnston, Alexander (1888). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (9th ed.).

- Picture of $5 US Treasury Note featuring George Thomas, provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

- The General George H. Thomas Home Page

- General George H. Thomas and Army of the Cumberland Source Page

- An article by Stephen Z. Starr about the relationship between Grant and Thomas