Witold Kieżun | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Witold Jerzy Kieżun |

| Nickname(s) | "Wypad" "2786" "Krak" |

| Born | 6 February 1922 Wilno, Poland (now Vilnius, Lithuania) |

| Died | 12 June 2021 (aged 99) Warsaw, Poland |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Union of Armed Struggle Home Army |

| Years of service | 1939–1945 |

| Rank | Podporucznik |

| Unit | "Baszta" Battalion "Karpaty" Battalion "Gustaw" Battalion |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Order of Virtuti Militari Several others (see below) |

Witold Jerzy Kieżun (6 February 1922 – 12 June 2021) was a Polish economist, soldier of the Home Army (the Polish resistance movement against German occupation during World War II), participant of the Warsaw uprising and prisoner in the Soviet Gulags. Kieżun was a former professor at Temple University, Duquesne University, Universite de Montreal, Université du Québec à Montréal, Bujumbura University, Warsaw University. He served as Chief Technical Advisor of the United Nations Development Programme in Burundi, Rwanda, and Burkina Faso. Witold Kieżun was a lecturer at Kozminski University in Warsaw. He received Doctor Honoris Causa from Jagiellonian University and the National Defence University of Warsaw. Kieżun was an honorary member of the Polish Academy of Sciences and an honorary citizen of Warsaw.

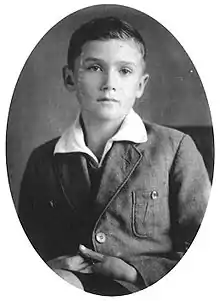

Early years

Witold Kieżun was born in 1922 in Wilno, to Witold Kieżun senior, a physician and officer of the Polish army and Leokadia Kieżun née Bokun, a dentist. Both parents were Catholic Poles. After the death of his older brother Zbigniew in 1930 and his father Witold Sr. in 1931, 9-year-old Witold moved with his mother to Warsaw.[1] They lived in the Żoliborz district, known as a preferred location for Polish Intelligentsia.

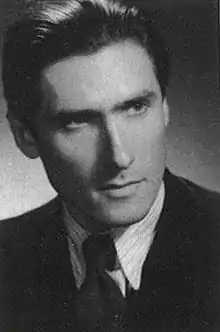

World War II

After Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, which launched World War II, 17-year-old Witold Kieżun was taken prisoner by the German army on 17 September, but managed to escape from the POW convoy and was hidden by a local farmer in an empty barrel.[2] After his escape, Witold returned to German-occupied Warsaw and moved back to Żoliborz with his mother. During that time the Kieżuns were providing shelter to their aunt Irena Kiełmuciowa, who was of Jewish descent, and to Witold's Catholic maternal cousin Leon Gieysztor. In 1940 Leon Gieysztor was arrested by Germans during a "Łapanka" (Roundup), and sent to Auschwitz concentration camp, where Leon died in December 1940.[3]

During the first years of Nazi German occupation after Poland's defeat, Witold jobbed as a glass-cutter and was a student of the Technical Vocational School (formerly an engineering school, which had been transformed into a vocational school by the German occupation regime, as Germans had banned higher education for Poles). One of Witold's classmates was Jan Bytnar, codename "Rudy", a prominent member of the Polish Scouting Resistance. Among Witold's lecturers was Professor Huber. Kieżun graduated from a vocational school in 1943. In 1942 Kieżun enrolled in the Law School of the secret Warsaw Underground University, where he completed the first year of curriculum before the clandestine program was interrupted by the Warsaw uprising in 1944.[4]

From 1939 onwards Witold Kieżun participated in the Polish resistance movement in World War II. From 1944 Witold's apartment in Żoliborz served as a weapon storage location of the Home Army.[5] Witold actively participated in the Warsaw uprising throughout its duration, under the code name "Wypad", serving in the special combat unit "Harnaś" at the rank of Second Lieutenant.[6] In August 1944 Witold Kieżun was awarded the Cross of Valour, amongst other things for taking 14 German soldiers captive and securing 14 rifles and 2000 rounds of ammunition.[7] On 23 September 1944 Witold Kieżun was decorated with Poland's highest military order Virtuti Militari personally by Commander in Chief Tadeusz Bor-Komorowski.[8] After the capitulation of the uprising on 3 October, Witold became prisoner of war, but once again managed to escape from a prisoner convoy.[9] Due to the near-complete destruction of Warsaw by the Germans following the defeat of the Warsaw Uprising, Witold relocated to Kraków using forged documents under the name of Jerzy Jezierza.[10] In Krakv Witold reunited with his mother, who had escaped from destroyed Warsaw.

Communist Poland

After the Soviet Red Army seized Kraków from German troops on 17 January 1945, Witold Kieżun enlisted in the Law School at the reopened Jagiellonian University. On 9 March 1945 Kieżun was arrested by the NKVD as part of Soviet repressions against members of the Polish Anti-Nazi resistance Home Army with the objective of strengthening the imposed Communist rule over post-war Poland. Kieżun was imprisoned in Kraków's infamous Montelupich Prison and intensively interrogated for his participation in the Warsaw Uprising and membership in the Home Army by Polish and Russian-speaking members of the NKVD. In March 1945, a mock execution was conducted, in which Kieżun and his fellow inmates were led to the prison yard and stood against a wall in front of a firing squad. Before the execution was performed, a senior NKVD officer arrived with orders to cancel the execution; Kieżun and the others were led back to their cell.[11]

On 23 March 1945, Witold Kieżun was removed from Montelupich Prison and transported on a Soviet freight train prisoner transport, together with other imprisoned Polish Home Army members as well as German POWs, to a Gulag labor camp in the Soviet Union, near the city of Krasnovodsk (currently Türkmenbaşy in Turkmenistan). Witold Kieżun's paternal uncle, Jan Kieżun, was also deported to the same labor camp. The transport took 31 days and arrived in the labor camp on 23 April. The labor camp was located in the Karakum Desert. Prisoners were provided with very limited food rations and contaminated water and suffered from a variety of diseases, which led to a death rate between 60% to 86%[12] over a period of 4 months after Kieżun's arrival. Witold Kieżun reported that the labor camp and NKVD guards used US military equipment provided to the Soviet Union as part of the Lend-Lease program and still bore US Army marking.[13]

During his stay in the camp, Witold Kieżun contracted pneumonia, typhoid fever, typhus, dystrophy, scabies, mumps and Beriberi. On 22 June Kieżun, who had fallen unconscious, was erroneously declared dead from pneumonia and his body was placed on a pile of corpses of other deceased patients. However, a nurse noticed the mistake and Kieżun was restored to the hospital, where he gradually recovered, although suffering from consequences of late stage Beriberi throughout his life. His death was also reported by a Polish fellow prisoner to Kieżun's mother in Krakow after the prisoner's release and return.[14] In September 1945 the camp was disbanded and on 20 September Kieżun was relocated to an NKVD hospital in Kogon, currently Uzbekistan, where he was imprisoned along with Japanese POWs. In April 1946 Witold Kieżun was released to return to Poland. First, he was sent back to an NKVD camp in Brest, where he was taken over by the Polish Communist Ministry of Public Security and imprisoned in a prisoner camp in Złotów. He was released by mid-1946.[15]

In October 1946 Witold Kieżun re-enrolled in the Law Program of Jagiellonian University in Kraków and started working for the National Bank of Poland. In 1948 Kieżun was arrested again for 48 hours by Ministry of Public Security due to his former membership in the Polish Resistance. Kieżun graduated in Law in June 1949 and moved from Krakow to Warsaw in August of that year. In 1950, Witold married Danuta who had been a paramedic during the Warsaw Uprising.[16]

Over the course of the 1950s and 1960s Witold Kieżun worked at the National Bank of Poland in Warsaw and pursued an academic career in Economics at the Main School of Planning and Statistics – currently the Warsaw School of Economics. Kieżun completed his doctorate studies in Economics in 1964. Under the guidance of prof. Tadeusz Kotarbiński and prof. Jan Zieleniewski, Witold Kieżun became a major representative of the Polish School of Praxeology. In 1971 Kieżun became the head of the Institute of Praxeology of the Polish Academy of Sciences. In 1973 he was fired from the post due to a request of the Institute's communist party unit. Over the next years he was employed as a lecturer at Warsaw University. He was granted the title of professor in 1975. From 1974 onwards Witold Kieżun was invited to hold a series of guest lectures in the United States and Canada: Seton Hall in 1974, Duquesne University in Pittsburgh in 1977 and University of Montreal in 1978, while still residing full-time in Poland until 1980.[17]

Emigration

On 6 September 1980 Witold Kieżun left Poland for a contract as lecturer at the School of Business and Administration at Temple University in Philadelphia. From 1980 to 1981 he held a series of lectures about the Solidarity Movement in Poland entitled "The Spirit of Solidarity" in 14 US and Canadian Universities.

In 1981–83 Witold Kieżun worked as Technical Advisor to the UNDP in Burundi, Africa.

After the end of his first contract in Burundi, Kieżun was meant to rejoin the faculty of Temple University, but the offer was revoked at the last minute, due to the university faculty's erroneous association with the Polish Anti-Nazi resistance Home Army of which Kieżun was a member, with collaboration with the Germans, propaganda lie deliberately spread by Stalin.[18] (See Anti-Polonism).

From 1983 to 1986 Kieżun was a professor at HEC Montréal. Kieżun returned to Burundi in 1986 as Chief Technical Advisor for the UNDP and directed the program until 1991. He was an advisor to President Pierre Buyoya. From 1989 to 1991 Kieżun was a professor at Bujumbura University. In 1990, Witold Kieżun met with Polish Pope John Paul II during his visit to Burundi.

Throughout the 1990s, Witold Kieżun alternated between roles as Chief Technical Advisor to UNDP in Rwanda (1991–1992) and Burkina Faso (1994) and his position as lecturer in Canada at the Universite de Quebec and McGill. During his time in Canada, Kieżun was co-organizer of the Canadian Foundation of Polish-Jewish Heritage in Montreal.[19]

Return to Poland

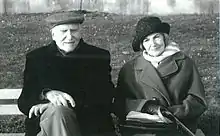

After the fall of Communism in Poland, Witold Kieżun was being considered for the post of Minister of Finance in the government of Tadeusz Mazowiecki, but he turned down the offer due to the lack of specificity of the request and his commitment to his UNDP project in Burundi.[20] In 1995 Witold Kieżun started giving regular 6-week long courses of international administration at Leon Kozminski Academy of Entrepreneurship and Management in Warsaw, where he became professor, but he still resided full-time in Canada until 1999, when he and his wife Danuta permanently moved back to Warsaw in Poland, where Witold continued to work as a lecturer, author and advisor.

During the 1990s, Witold Kieżun developed several propositions related to the administrative transformation of Poland and other post-communist states, e.g. the East European Countries Administrative Modernization for Nations Building project for the United Nations' Department of Technical Cooperation for Development. Witold Kieżun provided advice to the governments of Hanna Suchocka (1992–93), Jerzy Buzek (1997–2001), Marek Belka (2004–2005) and Jarosław Kaczyński (2006–2007) as well as to president Lech Kaczyński.[21]

Witold Kieżun's assessment of the economical and administrative development of post-transformation Poland has been generally critical. Kieżun claimed that the chosen path of economic transformation after the end of Communism had not taken into account the specifics of the Polish economy and that the applied "shock therapy" did not focus on preserving and modernizing existing assets, but unnecessarily handed over public assets to foreign companies and members of the former Communist party elite at drastically understated valuations. Kieżun attributed this to a lack of interest and knowledge of the economics of the political elite in Poland during the transformation years, in particular the government of Tadeusz Mazowiecki, as well as too much academic and detached-from-reality textbook liberalism of then finance minister Leszek Balcerowicz and Poland's foreign advisors such as George Soros and Jeffrey Sachs. While Kieżun admitted that the chosen path ultimately helped stop hyperinflation, according to Kieżun Poland's economic transformation resulted in creating a post-colonial state of dependence which puts at risk the future economic development of Poland. As support for his thesis Kieżun referred to annual profit outflows by foreign-owned companies in the range of 40–80 billion Polish Zloty (~3–5% of Poland's GDP), a too low share of wages in GDP, mass emigration, high unemployment and a very low fertility rate. Witold Kieżun has also been critical of the administrative transformation of Poland, stating that it served short-term political interests by creating unnecessary complexity and an excess of public servant posts while sacrificing government efficiency.[22]

On 9 January 2001, Witold Kieżun was kidnapped at gunpoint from a parking lot at Polna street in Warsaw by 2 unidentified men who knew his identity. The kidnappers drove Kieżun out of Warsaw in his own car, took his cell phone and address book, but were not interested in the money he carried or his Swiss watch. Ultimately, the kidnappers left Kieżun in a forest near Otwock, and drove off with his car, which was later found undamaged near Marysin. The background of the kidnapping has never been clarified.[23]

Witold Kieżun also frequently commented on Polish history, in particular related to the Second World War and the ongoing Polish debate about the justification and sense of the Warsaw uprising. Kieżun believed that the Uprising was a necessity because the population of Warsaw longed to actively put an end to the genocidal occupation of Warsaw by the Germans. As the specific trigger for the Uprising, Kieżun saw the German order to participate in the transformation of the city into "Festung Warschau", a German military concept of the total resistance in a city to maximize the slow-down of the Soviet advance, taking into account the city's complete destruction. The population of Warsaw refused to follow the order, which was punishable with death by German occupying forces and would have affected roughly 100 thousand male inhabitants of Warsaw, had the Uprising not begun. Also, Kieżun stressed insurgents' belief that the West would provide strong air support and could not have anticipated the lack of meaningful outside support for the Uprising.[24]

On 1 September 2014 the Polish Post issued a postage stamp bearing Kieżun's original picture from the Warsaw uprising to commemorate the 70th Anniversary of the outbreak of the Uprising.[25] 92-year-old (as of 2014) Witold Kieżun continued writing articles and delivering lectures to various audiences, and he was also working on a new book on the Polish transformation.

Personal life

Witold Kieżun was married to Danuta Magreczyńska, who had served as a paramedic of the Polish resistance Home Army during World War II (Code Name "Jola"). Danuta Kieżun died on 9 August 2013. Witold Kieżun has two children: one daughter Krystyna Macqueron (born 1951) who resides in France and one son Witold Olgierd Kieżun (born 1954) who lives in the United States. Witold Kieżun has three grandchildren – Aurelie, Charlotte and Adam.

Kieżun died in Warsaw in June 2021 at the age of 99. He is buried at the Powązki Military Cemetery.[26]

Awards and decorations

| Silver Cross of the Order of Virtuti Militari | Commander's Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta | ||||||||||

| Knight's Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta | Cross of Valour | Gold Cross of Merit | |||||||||

| Silver Cross of Merit | Medal of Victory and Freedom 1945 | Medal of Merit for National Defence (Silver) | |||||||||

| Medal of Merit for National Defence (Bronze) |

Medal of the 10th Anniversary of People's Poland | Badge of the 1000th Anniversary of the Polish State | |||||||||

| Medal of the National Education Commission | Pro Patria Medal | Member of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany | |||||||||

Publications (selection)

- 2014 – Niezapomniane twarze

- 2013 – Magdulka i cały świat. Rozmowa biograficzna z Witoldem Kieżunem przeprowadzona przez Roberta Jarockiego.

- 2012 – Drogi i bezdroża polskich przemian

- 2012 – Patologia transformacji

- 2003 – O odbudowę kapitału społecznego

- 1997 – Sprawne zarządzanie organizacją

- 1994 – Successful, though short lived sociotechnics

- 1992 – Management Efficient

- 1991 – Management in Socialist Countries

- 1990 – Manuel sur l’analyse des travaux administratifs

- 1990 – Problematique generale de la reforme administrative dans le monde

- 1984 – Organisation et Gestion

- 1978 – Ewolucja systemów zarządzania

- 1977 – Podstawy organizacji i zarządzania

- 1977 – Autonomization of Organizational Units. From Pathology of Organization

- 1974 – Organizace prace reditele

- 1971 – Organizacja pracy własnej dyrektora

- 1971 – Autonomizacja jednostek organizacyjnych. Z patologii zarządzania

- 1968 – Dyrektor. Z problematyki zarządzania instytucją

- 1965 – Organizacja bankowości w Polsce Ludowej

- 1964 – Bank a przedsiębiorstwo

References

- ↑ Jarocki, Robert (2013). Magdulka i cały świat. Rozmowa biograficzna z Witoldem Kieżunem przeprowadzona przez Roberta Jarockiego. Iskry. p. 92. ISBN 978-83-244-0325-7.

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), pp.92–93

- ↑ "Klub Inteligencji Polskiej". Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), pp.102–110

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), 125

- ↑ "Warsaw Uprising Museum". Witold Kieżun's short bio on the website of the Warsaw Uprising Museum. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ↑ "Gazeta Wyborcza (online edition)". Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), p. 148

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), p. 156

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), p. 158

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), pp. 174–176

- ↑ "Witold Kieżun, Armia Krajowa jedzie na Sybir. Wspomnienia z sowieckiego łagru w Krasnowodsku".

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), p. 195

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), p 205

- ↑ "Prof. Witold Kieżun: "Mogłem rozpocząć powstanie"". Radio Kraków.

- ↑ Legutko, Piotr (15 May 2014). "Bohater niespełniony". Gość Niedzielny.

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), pp. 441

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), p. 475

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), p. 518.

- ↑ "Polska Afryką Europy. Transformacja była klasyczną neokolonizacją; Forsal 2013". 8 November 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), pp. 523–528;545–547

- ↑ Kieżun, Witold (2013). Patologia transformacji. Poltext.

- ↑ Jarocki (2013), pp. 528–532

- ↑ "Prof. Kieżun: "Powstanie było najwspanialszym okresem"". Stefczyk.info.

- ↑ "Prof. Witold Kieżun na powstańczym znaczku". Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ↑ Nie żyje prof. Witold Kieżun. Powstaniec warszawski miał 99 lat

External links

- Witold Kieżun – personal homepage

- Biography of Witold Kiezun on http://www.warsawuprising.com/, a website dedicated to the Warsaw Uprising co-created by the son of Witold J. Kieżun.

- A Facebook page dedicated to Witold Kieżun: https://www.facebook.com/profwitoldkiezun

- Witold Kieżun speaks about his book "Patologia Transformacji" (Polish language) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YWQwKq6tNE0