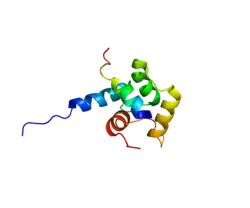

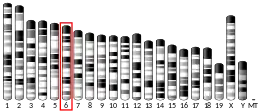

Xeroderma pigmentosum, complementation group C, also known as XPC, is a protein which in humans is encoded by the XPC gene. XPC is involved in the recognition of bulky DNA adducts in nucleotide excision repair.[4] It is located on chromosome 3.[5]

Function

This gene encodes a component of the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway. There are multiple components involved in the NER pathway, including Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) A-G and V, Cockayne syndrome (CS) A and B, and trichothiodystrophy (TTD) group A, etc. This component, XPC, plays an important role in the early steps of global genome NER, especially in damage recognition, open complex formation, and repair protein complex formation.[4]

The complex of XPC-RAD23B is the initial damage recognition factor in global genomic nucleotide excision repair (GG-NER).[6] XPC-RAD23B recognizes a wide variety of lesions that thermodynamically destabilize DNA duplexes, including UV-induced photoproducts (cyclopyrimidine dimers and 6-4 photoproducts ), adducts formed by environmental mutagens such as benzo[a]pyrene or various aromatic amines, certain oxidative endogenous lesions such as cyclopurines and adducts formed by cancer chemotherapeutic drugs such as cisplatin. The presence of XPC-RAD23B is required for assembly of the other core NER factors and progression through the NER pathway both in vitro and in vivo.[7] Although most studies have been performed with XPC-RAD23B, it is part of a trimeric complex with centrin-2, a calcium-binding protein of the calmodulin family.[7]

Clinical significance

Mutations in this gene or some other NER components result in Xeroderma pigmentosum, a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by increased sensitivity to sunlight with the development of carcinomas at an early age.[4]

Cancer

DNA damage appears to be the primary underlying cause of cancer,[8] and deficiencies in DNA repair genes likely underlie many forms of cancer.[9][10] If DNA repair is deficient, DNA damage tends to accumulate. Such excess DNA damage may increase mutations due to error-prone translesion synthesis. Excess DNA damage may also increase epigenetic alterations due to errors during DNA repair.[11][12] Such mutations and epigenetic alterations may give rise to cancer.

Reductions in expression of DNA repair genes (usually caused by epigenetic alterations such as promoter hypermethylation) are very common in cancers, and are ordinarily much more frequent than mutational defects in DNA repair genes in cancers. The table below shows that XPC expression was frequently epigenetically reduced in bladder cancer and also in non-small cell lung cancer, and also shows that XPC was more frequently reduced in the more advanced stages of these cancers.

| Cancer | Frequency | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Bladder cancer | 50% | [13] |

| Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential | 35% | [13] |

| Low grade papillary bladder cancer | 42% | [13] |

| High grade papillary bladder cancer | 65% | [13] |

| Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | 70% | [14] |

| NSCLC Stage I | 62% | [14] |

| NSCLC Stages II-III | 77% | [14] |

While epigenetic hypermethylation of the promoter region of the XPC gene was shown to be associated with low expression of XPC,[13] another mode of epigenetic repression of XPC may also occur by over-expression of the microRNA miR-890.[15]

Interactions

XPC (gene) has been shown to interact with ABCA1,[16] CETN2[17] and XPB.[18]

References

- 1 2 3 GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000030094 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- 1 2 3 "Entrez Gene: XPC xeroderma pigmentosum, complementation group C".

- ↑ "OMIM Entry - # 278720 - XERODERMA PIGMENTOSUM, COMPLEMENTATION GROUP C; XPC". Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ↑ Sugasawa K, Ng JM, Masutani C, Iwai S, van der Spek PJ, Eker AP, Hanaoka F, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH (1998). "Xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein complex is the initiator of global genome nucleotide excision repair". Mol. Cell. 2 (2): 223–32. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80132-x. PMID 9734359.

- 1 2 Schärer OD (Oct 2013). "Nucleotide excision repair in eukaryotes". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 5 (10): a012609. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a012609. PMC 3783044. PMID 24086042.

- ↑ Kastan MB (2008). "DNA damage responses: mechanisms and roles in human disease: 2007 G.H.A. Clowes Memorial Award Lecture". Mol. Cancer Res. 6 (4): 517–24. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0020. PMID 18403632.

- ↑ Harper JW, Elledge SJ (2007). "The DNA damage response: ten years after". Mol. Cell. 28 (5): 739–45. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.015. PMID 18082599.

- ↑ Dietlein F, Reinhardt HC (2014). "Molecular pathways: exploiting tumor-specific molecular defects in DNA repair pathways for precision cancer therapy". Clin. Cancer Res. 20 (23): 5882–7. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1165. PMID 25451105.

- ↑ O'Hagan HM, Mohammad HP, Baylin SB (2008). "Double strand breaks can initiate gene silencing and SIRT1-dependent onset of DNA methylation in an exogenous promoter CpG island". PLOS Genetics. 4 (8): e1000155. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000155. PMC 2491723. PMID 18704159.

- ↑ Cuozzo C, Porcellini A, Angrisano T, Morano A, Lee B, Di Pardo A, Messina S, Iuliano R, Fusco A, Santillo MR, Muller MT, Chiariotti L, Gottesman ME, Avvedimento EV (Jul 2007). "DNA damage, homology-directed repair, and DNA methylation". PLOS Genetics. 3 (7): e110. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030110. PMC 1913100. PMID 17616978.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yang J, Xu Z, Li J, Zhang R, Zhang G, Ji H, Song B, Chen Z (2010). "XPC epigenetic silence coupled with p53 alteration has a significant impact on bladder cancer outcome". J. Urol. 184 (1): 336–43. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.044. PMID 20488473.

- 1 2 3 Yeh KT, Wu YH, Lee MC, Wang L, Li CT, Chen CY, Lee H (2012). "XPC mRNA level may predict relapse in never-smokers with non-small cell lung cancers". Ann. Surg. Oncol. 19 (3): 734–42. doi:10.1245/s10434-011-1992-9. PMID 21861227. S2CID 19154489.

- ↑ Hatano K, Kumar B, Zhang Y, Coulter JB, Hedayati M, Mears B, Ni X, Kudrolli TA, Chowdhury WH, Rodriguez R, DeWeese TL, Lupold SE (2015). "A functional screen identifies miRNAs that inhibit DNA repair and sensitize prostate cancer cells to ionizing radiation". Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (8): 4075–86. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv273. PMC 4417178. PMID 25845598.

- ↑ Shimizu Y, Iwai S, Hanaoka F, Sugasawa K (January 2003). "Xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein interacts physically and functionally with thymine DNA glycosylase". EMBO J. 22 (1): 164–73. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg016. PMC 140069. PMID 12505994.

- ↑ Araki M, Masutani C, Takemura M, Uchida A, Sugasawa K, Kondoh J, Ohkuma Y, Hanaoka F (June 2001). "Centrosome protein centrin 2/caltractin 1 is part of the xeroderma pigmentosum group C complex that initiates global genome nucleotide excision repair". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (22): 18665–72. doi:10.1074/jbc.M100855200. PMID 11279143.

- ↑ Yokoi M, Masutani C, Maekawa T, Sugasawa K, Ohkuma Y, Hanaoka F (March 2000). "The xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein complex XPC-HR23B plays an important role in the recruitment of transcription factor IIH to damaged DNA". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (13): 9870–5. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.13.9870. PMID 10734143.

Further reading

- Cleaver JE, Thompson LH, Richardson AS, States JC (1999). "A summary of mutations in the UV-sensitive disorders: xeroderma pigmentosum, Cockayne syndrome, and trichothiodystrophy". Hum. Mutat. 14 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)14:1<9::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-6. PMID 10447254. S2CID 24148589.

- El-Deiry WS (2003). "Transactivation of repair genes by BRCA1". Cancer Biol. Ther. 1 (5): 490–1. doi:10.4161/cbt.1.5.162. PMID 12496474.

- Sugasawa K (2007). "UV-induced ubiquitylation of XPC complex, the UV-DDB-ubiquitin ligase complex, and DNA repair". J. Mol. Histol. 37 (5–7): 189–202. doi:10.1007/s10735-006-9044-7. PMID 16858626. S2CID 817898.

- Legerski R, Peterson C (1993). "Expression cloning of a human DNA repair gene involved in xeroderma pigmentosum group C". Nature. 360 (6404): 610. doi:10.1038/360610b0. PMID 1461286.

- Legerski R, Peterson C (1992). "Expression cloning of a human DNA repair gene involved in xeroderma pigmentosum group C". Nature. 359 (6390): 70–3. Bibcode:1992Natur.359...70L. doi:10.1038/359070a0. PMID 1522891. S2CID 34276965.

- Legerski RJ, Liu P, Li L, Peterson CA, Zhao Y, Leach RJ, Naylor SL, Siciliano MJ (1994). "Assignment of xeroderma pigmentosum group C (XPC) gene to chromosome 3p25". Genomics. 21 (1): 266–9. doi:10.1006/geno.1994.1256. PMID 8088800.

- Maruyama K, Sugano S (1994). "Oligo-capping: a simple method to replace the cap structure of eukaryotic mRNAs with oligoribonucleotides". Gene. 138 (1–2): 171–4. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90802-8. PMID 8125298.

- Masutani C, Sugasawa K, Yanagisawa J, Sonoyama T, Ui M, Enomoto T, Takio K, Tanaka K, van der Spek PJ, Bootsma D (1994). "Purification and cloning of a nucleotide excision repair complex involving the xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein and a human homologue of yeast RAD23". EMBO J. 13 (8): 1831–43. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06452.x. PMC 395023. PMID 8168482.

- Li L, Bales ES, Peterson CA, Legerski RJ (1994). "Characterization of molecular defects in xeroderma pigmentosum group C". Nat. Genet. 5 (4): 413–7. doi:10.1038/ng1293-413. PMID 8298653. S2CID 24923699.

- Li L, Peterson C, Legerski R (1996). "Sequence of the mouse XPC cDNA and genomic structure of the human XPC gene". Nucleic Acids Res. 24 (6): 1026–8. doi:10.1093/nar/24.6.1026. PMC 145764. PMID 8604333.

- van der Spek PJ, Eker A, Rademakers S, Visser C, Sugasawa K, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH (1996). "XPC and human homologs of RAD23: intracellular localization and relationship to other nucleotide excision repair complexes". Nucleic Acids Res. 24 (13): 2551–9. doi:10.1093/nar/24.13.2551. PMC 145966. PMID 8692695.

- Li L, Lu X, Peterson C, Legerski R (1997). "XPC interacts with both HHR23B and HHR23A in vivo". Mutat. Res. 383 (3): 197–203. doi:10.1016/s0921-8777(97)00002-5. PMID 9164480.

- Suzuki Y, Yoshitomo-Nakagawa K, Maruyama K, Suyama A, Sugano S (1997). "Construction and characterization of a full length-enriched and a 5'-end-enriched cDNA library". Gene. 200 (1–2): 149–56. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00411-3. PMID 9373149.

- Zeng L, Quilliet X, Chevallier-Lagente O, Eveno E, Sarasin A, Mezzina M (1998). "Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer corrects DNA repair defect of xeroderma pigmentosum cells of complementation groups A, B and C". Gene Ther. 4 (10): 1077–84. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3300495. PMID 9415314.

- Khan SG, Levy HL, Legerski R, Quackenbush E, Reardon JT, Emmert S, Sancar A, Li L, Schneider TD, Cleaver JE, Kraemer KH (1998). "Xeroderma pigmentosum group C splice mutation associated with autism and hypoglycinemia". J. Invest. Dermatol. 111 (5): 791–6. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00391.x. PMID 9804340.

- Yokoi M, Masutani C, Maekawa T, Sugasawa K, Ohkuma Y, Hanaoka F (2000). "The xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein complex XPC-HR23B plays an important role in the recruitment of transcription factor IIH to damaged DNA". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (13): 9870–5. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.13.9870. PMID 10734143.

- Batty D, Rapic'-Otrin V, Levine AS, Wood RD (2000). "Stable binding of human XPC complex to irradiated DNA confers strong discrimination for damaged sites". J. Mol. Biol. 300 (2): 275–90. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.3857. PMID 10873465.

- Araújo SJ, Nigg EA, Wood RD (2001). "Strong functional interactions of TFIIH with XPC and XPG in human DNA nucleotide excision repair, without a preassembled repairosome". Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 (7): 2281–91. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.7.2281-2291.2001. PMC 86862. PMID 11259578.

- Araki M, Masutani C, Takemura M, Uchida A, Sugasawa K, Kondoh J, Ohkuma Y, Hanaoka F (2001). "Centrosome protein centrin 2/caltractin 1 is part of the xeroderma pigmentosum group C complex that initiates global genome nucleotide excision repair". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (22): 18665–72. doi:10.1074/jbc.M100855200. PMID 11279143.