| Yari (槍) | |

|---|---|

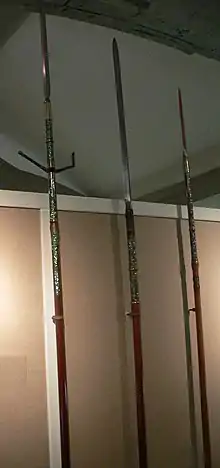

Yari forged by Echizen Kanenori, 17th century, Edo period (left), sasaho yari forged by Tachibana no Terumasa, 1686, Edo period (middle), and jūmonji yari forged by Kanabo Hyoeno jo Masasada, 16th century, Muromachi period (right). | |

| Type | Spear |

| Place of origin | Japan |

| Production history | |

| Produced | Nara period (710–794) for Hoko yari, Muromachi period (1333–1568) for Yari, since 1334[1] |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 1.27 kg (2.8 lb) |

| Length | 1–6 m (3 ft 3 in – 19 ft 8 in) |

| Blade length | 15–60 cm (5.9–23.6 in) |

| Blade type | multiple blade shapes |

| Hilt type | Wood, horn, lacquer |

| Scabbard/sheath | Lacquered wood |

Yari (槍) is the term for a traditionally-made Japanese blade (日本刀; nihontō)[2][3] in the form of a spear, or more specifically, the straight-headed spear.[4] The martial art of wielding the yari is called sōjutsu.

History

The forerunner of the yari is thought to be a hoko yari derived from a Chinese spear. These hoko yari are thought to be from the Nara period (710–794).[5][6]

The term 'yari' appeared for the first time in written sources in 1334, but this type of spear did not become popular until the late 15th century.[1] The original warfare of the bushi was not a thing for commoners; it was a ritualized combat usually between two warriors who would challenge each other via horseback archery.[7] In the late Heian period, battles on foot began to increase and naginata, a polearm, became a main weapon along with a yumi (longbow).[8]

The attempted Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281 was one of the factors that changed Japanese weaponry and warfare. The Mongols employed Chinese and Korean footmen wielding long pikes and fought in tight formations. They moved in large units to stave off cavalry.[7] Polearms (including naginata and yari) were of much greater military use than swords, due to their significantly longer reach, lighter weight per unit length (though overall a polearm would be fairly hefty), and their great piercing ability.[7]

In the Nanbokuchō period, battles on foot by groups became the mainstream and the importance of naginata further increased, but yari were not yet the main weapon. However, after the Onin War in 15th century in the Muromachi period, large-scale group battles started in which mobilized ashigaru (foot troops) fought on foot and in close quarters, and yari, yumi (longbow) and tanegashima (Japanese matchlock) became the main weapons. This made naginata and tachi obsolete on the battlefield, and they were often replaced with nagamaki and short, lightweight katana.[8][9][10][11]

Around the latter half of the 16th century, ashigaru holding pikes (nagae yari) with length of 4.5 to 6.5 m (15 to 21 ft) became the main forces in armies. They formed lines, combined with soldiers bearing firearms tanegashima and short spears. Pikemen formed a two- or three-row line, and were trained to move their pikes in unison under command. Not only ashigaru but also samurai fought on the battlefield with yari as one of their main weapons. For example, Honda Tadakatsu was famous as a master of one of The Three Great Spears of Japan, the Tonbokiri (蜻蛉切). One of The Three Great Spears of Japan, the Nihongō (ja:日本号) was treasured as a gift, and its ownership changed to Emperor Ogimachi, Shogun Ashikaga Yoshiaki, Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Fukushima Masanori, and so on, and has been handed down to the present day.[12][13]

With the coming of the Edo period the yari had fallen into disuse. Greater emphasis was placed on small-scale, close quarters combat, so the convenience of swords led to their dominance, and polearms and archery lost their practical value. During the peaceful Edo period, yari were still produced (sometimes even by renowned swordsmiths), although they existed mostly as either a ceremonial weapon or as a police weapon.[12]

Description

_omi_yari.jpg.webp)

Yari were characterized by a straight blade that could be anywhere from several centimeters to 3 feet (0.91 m) or more in length.[4] The blades were made of the same steel (tamahagane) from which traditional Japanese swords and arrowheads were forged, and were very durable.[4] Throughout history many variations of the straight yari blade were produced, often with protrusions on a central blade. Yari blades often had an extremely long tang (nakago; 中心); typically it would be longer than the sharpened portion of the blade. The tang protruded into a reinforced hollow portion of the handle (tachiuchi or tachiuke) resulting in a very stiff shaft making it nearly impossible for the blade to fall or break off.[4]

The shaft (nagaye or ebu) came in many different lengths, widths, and shapes; made of hardwood and covered in lacquered bamboo strips, these came in oval, round, or polygonal cross section. These in turn were often wrapped in metal rings or wire (dogane), and affixed with a metal pommel (ishizuki; 石突) on the butt end. Yari shafts were often decorated with inlays of metal or semiprecious materials such as brass pins, lacquer, or flakes of pearl. A sheath (saya; 鞘) was also part of a complete yari.[4]

Variations of yari blades

Various types of yari points or blades existed. The most common blade was a straight, flat design that resembles a straight-bladed double edged dagger.[4] This type of blade could cut as well as stab and was sharpened like a razor edge. Though 'yari' is a catchall term for 'spear', it is usually distinguished between 'kama yari', which have additional horizontal blades, and simple 'su yari' (choku-sō) or straight spears. Yari can also be distinguished by the types of blade cross section: the triangular sections were called 'sankaku yari' and the diamond sections were called 'ryō-shinogi yari'.[4]

- Sankaku yari (三角槍, "triangle spear") have a point that resembles a narrow spike with a triangular cross-section. A sankaku yari therefore had no cutting edge, only a sharp point at the end. The sankaku yari was therefore best suited for penetrating armor, even armor made of metal, which a standard yari was not as suited to.[4] There are two types of sankaku yari: sei sankaku yari, yari blades with a triangular, equilateral cross section, and hira sankaku yari, yari with a triangular, isosceles-shaped cross section.

- Ryō-shinogi yari, a blade with a diamond shaped cross section.

- Fukuro yari (袋槍, "bag" or "socket spear") were mounted to a shaft by means of a metal socket instead of a tang. The socket and blade are forged from a single piece.

- Kikuchi yari (菊池槍, "spear of Kikuchi") were one of the rarest types of yari, possessing only a single edge. This created a weapon that could be used for hacking and closely resembled a tantō. Kikuchi yari are the only yari which use a habaki.

- Yajiri nari yari (鏃形槍, "spade-shaped spear") had a very broad, "spade-shaped" head. Yajiri nari yari often had a pair of holes centering the two ovoid halves.

- Jūmonji yari (十文字槍, "cross-shaped spear"), also called magari yari (曲槍, "curved spear"), looked something similar to a trident or partisan, and brandishing two curved side blades pointing upward. It is occasionally referred to as 'maga yari' in modern weaponry texts.

- Jogekama yari, a jūmonji yari with one side blade pointing downward and one side blade pointing upward.

- Karigata yari, a jūmonji yari with the two side blades pointing downward.

- Gyaku yari, a jūmonji yari with the two side blades resembling a pair of buffalo horns.

- Kama-yari (鎌槍, "sickle spear") gets its name from a peasant weapon called kama (lit. "sickle" or "scythe").

- Kata kamayari (片鎌槍, "single-sided sickle spear") had a weapon design sporting a blade that was two-pronged. Instead of being constructed like a military fork, a straight blade (as in su yari) was intersected just below its midsection by a perpendicular blade. This blade was slightly shorter than the primary, had curved tips making a parallelogram, and was set off center so that only 1/6 of its length extended on the other side. This formed a rough 'L' shape.

- Tsuki nari yari (月形槍, "moon-shaped spear") barely looked like a spear at all. A polearm that had a crescent blade for a spearhead, which could be used for slashing and hooking.

- Kagi yari (鉤槍, "hook spear") was a key-shaped spear with a long blade with a side hook much like that found on a fauchard. This could be used to catch another weapon, or even dismount a rider mounted on horseback.

- Bishamon yari (毘沙門槍) possessed some of the most ornate designs for any spear. Running parallel to the long central blade were two 'crescent moon' shaped blades facing outwards. They were attached in two locations by short cross bars, making the head look somewhat like a fleur-de-lis.

- Hoko yari, an old form of yari possibly from the Nara period (710–794),[14] a guard's spear with 6 ft (1.8 m) pole and 8 in (200 mm) blade either leaf-shaped or waved (like keris); a sickle-shaped horn projected on one or both sides at the joint of blade.[15] The hoko yari had a hollow socket like the later period fukuro yari for the pole to fit into rather than a long tang.[16]

- Sasaho yari (笹穂槍), a broad yari described as being "leaf shaped" or "bamboo leaf shaped".[17]

- Su yari (素槍, "simple spear") (alao known as sugu yari), a straight double edged blade.[18]

- Omi no yari (omi yari), an extra long su yari blade.[18]

- Makura-yari (枕槍, "pillow spear")

- Choku-yari (直槍, straight spear")[19]

Variations of yari shafts

A yari shaft can range in length from 1–6 metres (3 ft 3 in – 19 ft 8 in), with some in excess of 6 metres.

- Nagae yari ("long shafted spear"): 16.4 to 19.7 ft (5.0 to 6.0 m) long, a type of pike used by ashigaru.[20][21] It was especially used by Oda clan ashigaru beginning from the reign of Oda Nobunaga; samurai tradition of the time held that the soldiers of the rural province of Owari were among the weakest in Japan. Kantō was a chaotic place; Kansai was home to the Shogunate, and the Uesugi, Takeda, Imagawa, and Hojo clans, as well as pirate raiders from Shikoku. Additionally, Kyushu was home of one of the most warmongering clans in Japan, the Shimazu clan. Because of this, Nobunaga armed his underperforming ashigaru soldiers extra-long pikes in order for them to be more effective against armoured opponents and cavalry, and fighting in groups and formations.

- Mochi yari (持ち槍, "hand spear"), a long spear used by ashigaru and samurai.[22]

- Kuda yari (管槍, "tube spear"). The shaft goes through a hollow metal tube that allowed the spear to be twisted during thrusting. This style of sojutsu is typified in the school Owari Kan Ryū.

- Makura yari (枕槍, "pillow spear"). A yari with a short simple shaft that was kept by the bedside for home protection.[23]

- Te yari (手槍, "hand spear"). A yari with a short shaft that was used by samurai and police to help capture criminals.[24]

Gallery

Kikuchi yari

Kikuchi yari Sasaho yari

Sasaho yari Sankaku yari

Sankaku yari Ryo shinogi fukuro yari

Ryo shinogi fukuro yari Tachiuchi or tachiuke, the reinforced upper part of the shaft.

Tachiuchi or tachiuke, the reinforced upper part of the shaft.

See also

References

- 1 2 Friday, Karl (2004). Samurai, Warfare and The State in Early Medieval Japan. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 0-415-32962-0.

- ↑ The Development of Controversies: From the Early Modern Period to Online Discussion Forums, Volume 91 of Linguistic Insights. Studies in Language and Communication, Author Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, Publisher Peter Lang, 2008, ISBN 3-03911-711-4, ISBN 978-3-03911-711-6 P.150

- ↑ The Complete Idiot's Guide to World Mythology, Complete Idiot's Guides, Authors Evans Lansing Smith, Nathan Robert Brown, Publisher Penguin, 2008, ISBN 1-59257-764-4, ISBN 978-1-59257-764-4 P.144

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ratti, Oscar; Adele Westbrook (1991). Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan. Tuttle Publishing. p. 484. ISBN 978-0-8048-1684-7.

- ↑ Japan and China: Japan, its history, arts, and literature, Frank Brinkley, T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1903 p.156

- ↑ The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords, Kōkan Nagayama, Kodansha International, p.49

- 1 2 3 Deal, William E (2007). Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan. Oxford University Press. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-19-533126-4.

- 1 2 Basic knowledge of naginata and nagamaki. Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum, Touken World

- ↑ Arms for battle – spears, swords, bows. Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum, Touken World

- ↑ Kazuhiko Inada (2020), Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords. p42. ISBN 978-4651200408

- ↑ 歴史人 September 2020. pp.40–41. ASIN B08DGRWN98

- 1 2 歴史人 September 2020. pp.128–135. ASIN B08DGRWN98

- ↑ Three Great Spears of Japan. Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum, Touken World.

- ↑ The new generation of Japanese swordsmiths, Tamio Tsuchiko, Kenji Mishina, Kodansha International, 2002 p.15

- ↑ The Encyclopedia Americana: a library of universal knowledge, Volume 15 Encyclopedia Americana Corp., 1919 p.745

- ↑ The Japanese sword Kanzan Satō, Kodansha International, 1983 P.63

- ↑ The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords, Kōkan Nagayama, Kodansha International, 1998 p.49

- 1 2 The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords, Kōkan Nagayama, Kodansha International, 1998, P.49

- ↑ Armstrong, Hunter B. "The Sliding Yari of the Owari Kan Ryu". www.koryu.com. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ Fighting techniques of the Oriental world, AD 1200–1860: equipment, combat skills, and tactics, Authors Michael E. Haskew, Christer Joregensen, Eric Niderost, Chris McNab, Publisher Macmillan, 2008, ISBN 0-312-38696-6, ISBN 978-0-312-38696-2 P.44

- ↑ Ashigaru 1467–1649, Stephen Turnbull, Howard Gerrard, Osprey Publishing, 2001, P.19

- ↑ Ashigaru 1467–1649, Authors Stephen Turnbull, Howard Gerrard, Illustrated by Howard Gerrard, Publisher Osprey Publishing, 2001, ISBN 1-84176-149-4, ISBN 978-1-84176-149-7 P.23

- ↑ Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior, Author Clive Sinclaire, Publisher Globe Pequot, 2004, ISBN 1-59228-720-4, ISBN 978-1-59228-720-8 P.119

- ↑ Taiho-jutsu: law and order in the age of the samurai, Author, Don Cunningham, Publisher Tuttle Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8048-3536-5, ISBN 978-0-8048-3536-7 P.44