The Yosemite Firefall was a summer time event that began in 1872 and continued for almost a century, in which burning hot embers were spilled from the top of Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park to the valley 3,000 feet (900 m) below. From a distance it appeared as a glowing waterfall. The owners of the Glacier Point Hotel conducted the firefall. History has it that David Curry, founder of Camp Curry, would stand at the base of the fall, and yell "Let the fire fall," each night as a signal to start pushing the embers over. The Firefalls were performed at 9 p.m. seven nights a week as the final act of a performance at Camp Curry.

The Firefall ended in January 1968, when George B. Hartzog, then the director of the National Park Service, ordered it to stop because the overwhelming number of visitors that it attracted trampled the meadows, and because it was not a natural event. The NPS wanted to preserve the valley, returning it to its natural state. The Glacier Point Hotel was destroyed by fire 18 months later and was not rebuilt.

The spectacle of the Yosemite Firefall has evolved into a natural spectacle observed annually. Unlike the original man-made Firefall event, the modern-day phenomenon is a captivating interplay of nature's elements that occurs every February, replicating the appearance of a fiery waterfall without the use of actual fire in Horsetail Fall (Yosemite). Today's Firefall occurs at Horsetail Fall on El Capitan in Yosemite National Park, where the setting sun illuminates the waterfall, casting a warm, fiery glow that resembles a cascade of fire.

Nineteenth-century origins

In 1871, before Yosemite became a National Park, an Irish immigrant named James McCauley hired John Conway to build the Four Mile Trail from Yosemite Valley, where McCauley lived, to Glacier Point. When the trail was completed, McCauley built a small hotel called the Glacier Point Mountain House. McCauley and his wife Barbara operated the hotel during the summer months. In 1883, James McCauley sent for his niece, Elizabeth McCauley, to come from Ireland and help with the hotel.

McCauley's son Fred had an apple orchard just outside the park. His twin brother John told Ranger-Naturalist Bob Fry in 1961 that the Firefalls began spontaneously one day. James McCauley often made a large campfire for his guests on the point of the granite cliff that jutted out over the valley. All would sit around the fire and talk. At the end of the evening, McCauley would kick the glowing coals over the edge of the cliff. People in the valley were fascinated by the falling embers and mentioned it to McCauley's sons. Some visitors gave them money, saying things like "Here's two bits. Tell your father to have another firefall tonight." The sons decided this was a way to earn a little money. They gathered wood for a larger fire, carrying it up the mountain on their burros. James McCauley tied a gunny sack to a long pole and dipped in "coal oil". He would light the sack and wave it as a signal that the Firefall was about to begin. Then he would kick over the campfire coals and spectators would watch from below as the coals fell. The park placed a warning sign which read:

- It is 3,000 feet to the bottom

- And no undertaker to meet you

- TAKE NO CHANCES

- There is a difference

- Between bravery and just plain

- ORDINARY FOOLISHNESS

In 1897, the Washburn brothers, who owned the Wawona Hotel, had the Guardian of the State Grant evict James McCauley and took over his hotel at Glacier Point. They stopped the Firefalls.

The following year, McCauley bought John Lembert's homestead in Tuolumne Meadows and ran cattle there. He and his sons built a small cabin on the property at Tuolumne Meadows; today the "McCauley Cabin" houses park personnel. The McCauley family sold it to the Sierra Club in 1912, and the Sierra Club sold it to the National Park Service in 1973.

Camp Curry years

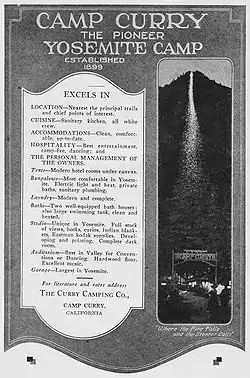

In 1899 David Curry established Camp Curry in Yosemite Valley. Soon he heard visitors reminiscing about the Firefall when McCauley ran the hotel at Glacier Point. Sometime in the early 1900s, Curry reestablished the Firefall during the summer season, when guests were at Camp Curry. He sent his employees to build a fire on the point and push it off on special occasions.

Curry prided himself on his booming voice. He would call up to Glacier Point to signal when the Firefall should begin:

- David Curry: Hello, Glacier Point.

- Glacier Point: Hello.

- David Curry: Let 'er go, Gallagher.

On May 31, 1913, Curry and Assistant Secretary of the Interior Adolph C. Miller had a confrontation over the Curry Camping Company's lease. Miller told him, "I'm going to take the Firefall away. There will be no Firefall." Curry felt that a rival company, the Desmond Park Service Company, had influenced the Park Service against him. From then on, he began the nightly entertainment program by saying "Welcome to Camp Curry, where the Stentor calls and fire used to fall." In 1916, Desmond built the Glacier Point Hotel, a large chalet-style hotel with a commanding view of Yosemite Valley, Vernal Fall, and Nevada Fall.

On March 8, 1917, Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane granted the Curry Camping Company a five-year lease and said that the Firefall could be reinstated as a nightly summertime event. David Curry died on April 30, but his widow and son opened Camp Curry as usual that summer and presided at the reintroduction of the Firefall. Foster Curry shouted "Let 'er go, Gallagher" and continued as the caller for many years.

The job of making the calls later was one that loud-voiced employees competed for.

- Camp Curry: Hello, Glacier Point.

- Glacier Point: Hello, Camp Curry.

- Camp Curry: Is the fire ready?

- Glacier Point: The fire is ready.

- Camp Curry: Let the fire fall.

- Glacier Point: The fire falls.

By 1960, the middle exchange ("Is the fire ready?"; "The fire is ready.") was eliminated.

As the fire fell, the "Indian Love Call" was sung at Camp Curry while visitors saw what seemed to be a waterfall of fire. At the campground sites where Ranger-Naturalists (as they were called then) gave nightly summer talks, "America the Beautiful" was played, and the audience sang along. The time of the Firefall was established as 9:00 p.m. The Ranger-Naturalists had to be careful to end their programs in the campgrounds and at Camp Curry right at 9:00, or the "fire would fall on the program." In 1962, President John F. Kennedy visited Yosemite National Park, and on that night an especially large fire was built on the Point to make a spectacular Firefall. President Kennedy was on the telephone at 9:00, so the Firefall was delayed until he finished, and the Firefall occurred around 9:30 p.m.

Sometime, probably by 1920, red fir bark was found to be the best fuel to produce an even flow of coals, so fires were made of red fir bark instead of wood. Employees would gather huge piles of the bark, which they stored near the hotel; each day a stack of the bark would be placed on the Valley side of the Point, to be lit that night and to burn for a couple hours to produce a bed of coals. Through the years, visitors to Glacier Point enjoyed watching the hotel employees gradually push the glowing embers off the cliff with long-handled metal pushers.

In 1925 all the rival business companies in the Park united to form the Yosemite Park and Curry Company under the direction of the Curry family. YPCC continued to be the concessionaire of Yosemite National Park until 1993 (Although the YPCC has been owned by various corporations in recent decades, the name remained unchanged).

During World War II the Firefall was cancelled. Some people in both the National Park Service and the Yosemite Park and Curry Company hoped that it would not be continued after the war. The NPS considered it an unnatural event in a natural area, and the task of presenting the Firefall each night was burdensome to YPCC. Employees drove trucks farther to find the red fir bark, because they were allowed to collect it only from trees that were dead and down. Before the Firefall ended, they were going as far as the Tioga Road.

After World War II, the public demanded the Firefall's return.

The end of a tradition

In January 1968, director George B. Hartzog of the Park Service ordered the Firefall be discontinued on the grounds such a man-made event was inconsistent with the Service mission to encourage appreciation of natural wonders. According to Hartzog, the firefall was as appropriate as "horns on a rabbit".[1] Also, the traffic was increasingly problematic, as each night a stream of cars left the campgrounds and meadow areas where people had gone to get the best views.

The last Firefall was on Thursday, January 25, 1968. Since it was winter, no crowd was present.

In popular culture

- The Firefall can be seen in the 1954 movie The Caine Mutiny when Willie Keith and his girlfriend, May Wynn, visit Yosemite for shore leave. The movie is based on the book of the same name, which also has the Firefall in it.

- In 1974, musician Rick Roberts named his band "Firefall" after the Yosemite spectacle.

- The dénouement of Richard P. Powell's novel Say It With Bullets takes place at the Firefall.

Modern-Day Firefalls

The allure of the Yosemite Firefall has transcended through time, evolving into a natural spectacle observed annually. Unlike the original man-made Firefall event, the modern-day phenomenon is a captivating interplay of nature's elements that occurs every February, replicating the appearance of a fiery waterfall without the use of actual fire in Horsetail Fall (Yosemite).[2][3]

Occurrence

Today's Firefall occurs at Horsetail Fall on El Capitan in Yosemite National Park, where the setting sun illuminates the waterfall, casting a warm, fiery glow that resembles a cascade of fire. This spectacle predominantly occurs from mid to late February, with the peak intensity usually observed around February 21 each year. The golden hues begin to appear approximately 35 minutes before sunset, with the vibrant orange and red colors becoming prominent 10–15 minutes before sunset. This natural marvel is highly dependent on the sun's specific angle of descent coupled with the availability of water in Horsetail Fall, which is subject to recent precipitation and snowmelt.[2][4]

Viewing details

Viewers can marvel at this phenomenon from various vantage points within the park, including the Four Mile Hike, Taft Point, El Cap Meadow, and Tunnel View. The waterfall itself is known as Horsetail Fall and is located on the far right side of El Capitan. For those planning to catch a glimpse of this wonder, the park has set specific dates in February when Temporary Vehicle Reservations are required to access the park, ensuring the experience remains serene and unspoiled.[4][2]

Reservations and access

In recent years, the influx of visitors keen on witnessing the Firefall has led to the implementation of a reservation system during the peak viewing period in February. For instance, in 2022, reservations were required for the entire month, while in 2023, they were necessary for weekends only. The park offers ample parking lots, with signs along North River Road near Yosemite Lodge guiding visitors to the designated parking areas. From the main parking lots, a walk of approximately 1.5 miles leads to the most common viewing areas.[2] A parking pass is available for $35 as well as a $2 reservation fee to view the Firefall.

Conservation considerations

The modern-day Firefall, while enthralling, also underscores the delicate balance between public enjoyment and conservation. The National Park Service, in its bid to maintain the natural integrity of Yosemite, regulates access during this period to mitigate potential environmental impacts. This measure ensures that the awe-inspiring Firefall continues to be a sustainable attraction for future generations, epitomizing the harmonious coexistence of human appreciation and natural preservation.

Modern interpretations and management of the tradition

The tradition of celebrating the spectacle of Firefalls at Yosemite National Park has transcended into the modern era with a natural phenomenon replacing the original man-made event. The modern-day Firefalls at Horsetail Fall have become a significant attraction, drawing visitors from all over, especially during the brief period in February when the Firefall can be viewed.[5] However, the management, promotion, and preservation of this tradition have evolved to adapt to contemporary challenges and opportunities.

Social media and digital engagement

The role of social media in popularizing the Firefall event is notable. Images and experiences shared on social platforms have significantly contributed to the growing popularity of the event, drawing more visitors each year, and fostering a digital community of nature enthusiasts and Yosemite admirers.[5] The digital engagement not only promotes the event but also serves as a platform for educating the public about the park's natural features and the importance of environmental conservation.

Park management and environmental concerns

The increasing popularity of the Firefall, particularly through social media exposure, has led to a surge in visitor numbers, causing environmental concerns like damage and increased erosion in the area. In response, the National Park Service has implemented new rules and established a reservation system to manage the crowds and mitigate environmental impact. The reservation system is aimed at alleviating parking congestion and ensuring a better visitor experience, with specific dates designated for viewing the Firefall.[6][7] This system helps to organize the influx of visitors, ensuring they have a pleasant experience while adhering to the park's conservation policies.

Through these measures, the National Park Service aims to balance the preservation of this cherished tradition with the essential goal of environmental conservation, ensuring that the modern-day Firefalls continue to awe and inspire while safeguarding the pristine beauty of Yosemite National Park.

References

- ↑ 'The National Parks: America's Best Idea' 2009 television series, season 1, episode 6

- 1 2 3 4 "The Ultimate Guide to Yosemite Firefalls in 2024". Dalton Johnson Media. 2023-09-01. Retrieved 2023-10-20.

- ↑ McFadden, Mimi (2022-01-05). "Yosemite Firefall: How to Experience it & When to Go". The Atlas Heart. Retrieved 2023-10-20.

- 1 2 ymctb (2022-02-09). "Yosemite Firefall | Yosemite National Park's Horsetail Fall". Discover Yosemite National Park. Retrieved 2023-10-20.

- 1 2 Palmer, Jordan (2021-03-02). "What It's Like To Experience Yosemite's Incredible Firefall In Person". TravelAwaits. Retrieved 2023-10-20.

- ↑ Vincent, Brittany (2023-02-21). "Yosemite's Long-Awaited Firefall Arrives—And the Photos Are Stunning". Outdoors with Bear Grylls. Retrieved 2023-10-20.

- ↑ "Yosemite Horsetail Fall 'Firefall' 2023: What you need to know". yosemite.org. 2022-12-13. Retrieved 2023-10-20.

- Lau, Tammy; Sitterding, Linda (2000). Yosemite National Park in Vintage Postcards. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-0884-9.

- "Horsetail Fall - Yosemite National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2023-10-17.

Bibliography

- Huber, N. K. (2001, November 21). Yosemite Falls - A new perspective. Yosemite. https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/70206784

- Sargent, Shirley. Pioneers in Petticoats: Yosemite's Early Women, 1856–1900. Los Angeles: Trans-Anglo Books, 1966.

- Sargent, Shirley. Yosemite & Its Innkeepers: The Story of a Great Park and Its Chief Concessionaires. Yosemite: Flying Spur Press, 1975.