Yusuf Gowon | |

|---|---|

| Uganda Army Chief of Staff | |

| In office June 1978 – March 1979 | |

| President | Idi Amin |

| Preceded by | Isaac Lumago |

| Succeeded by | Ali Fadhul |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Yusuf Mogi 1936 (age 87–88) Ladonga, West Nile Province, Uganda Protectorate |

| Nickname(s) | "Goan" "The tractor driver" "bad omen" "Snake" |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Uganda Army (UA) |

| Years of service | 1968–1979 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Battles/wars | |

Yusuf Gowon[lower-alpha 1] (born Yusuf Mogi in 1936) is an Ugandan retired military officer who served as chief of staff for the Uganda Army during the dictatorship of Idi Amin. Originally a farmer, Gowon quickly rose in the ranks of the military due to a combination of happenstance and his skills in politics. Compared with other high-ranking officials of Amin's regime, he was regarded as humane; nevertheless, he was probably involved in some political murders. His appointment as chief of staff was mostly owed to the fact that he was regarded by President Amin as loyal, not ambitious, and of no threat to his own rule. Gowon's lack of talent for tactics and strategy came to the fore when the Uganda–Tanzania War broke out in 1978, and his leadership of the Uganda Army during this conflict was extensively criticised. Many of his comrades and subordinates even blamed him for Uganda's defeat in the conflict with Tanzania. When Amin's regime began collapsing in 1979 and his own soldiers intended to murder him, Gowon fled Uganda.

He subsequently settled in Zaire where he worked as businessman. Unlike many of his former comrades, Gowon did not join any insurgent group during his exile. When the new Ugandan government of Yoweri Museveni offered him to return to his home country in 1994, he accepted and founded a nonprofit organization to help ex-combatants to find civilian jobs. He also became head of a veterans association. In 2001, Gowon was arrested and tried for the suspected involvement in the murder of Eliphaz Laki during Amin's rule. The trial generated much publicity and was controversial, as some regarded it as important chance to finally address the crimes of Amin's dictatorship, while others claimed that it was politically motivated. Gowon denied any involvement in Laki's murder, and was acquitted due to lack of evidence in 2003.

Biography

Early life

Gowon was born as Yusuf Mogi[3] in Ladonga, a village in the West Nile Province[4][lower-alpha 2] of the British Uganda Protectorate in 1936.[6] His father Ibrahim was born a Catholic Christian and an ethnic Kakwa, but converted to Islam and adopted a Nubian identity; as a result, Gowon's cheeks were cut with three marks after his birth, signalling him belonging to the Nubians.[7][lower-alpha 3] Though his family was not wealthy, his father was a clan chieftain and owned some farmland.[3] In his youth, Yusuf would help out on his family's farm by looking after its fields, goats and cows. Occasionally, he went hunting with bows and arrows.[10]

Ibrahim could only afford to send one of his children to an Islamic primary school in the provincial capital of Arua; he chose Yusuf.[3][10] To pay for his son's education, he sold some of his cattle to the disapproval of other clan elders who reminded Ibrahim that the West Nile region was too poor to offer any employment for educated men. Sending Yusuf to school was regarded as wasted money. Yusuf wanted to go to school, however, and convinced his father to pay a few years of tuition. In Arua, Yusuf stayed at the house of a family friend, working on the fields and helping in the household to earn his keep.[10] Arua served as center for the British colonial troops, the King's African Rifles, and many of Yusuf's classmates adored the military.[6] He was an exception in this regard, and showed no interest in military matters at all.[3][11] His classmates regarded him as sociable prankster who would entertain others with jokes and songs. Yusuf was known for dressing fashionably, thereby earning the nickname "Goan". This was a reference to the city of Goa in India, as the region's best tailors were Indians. Having taken a great liking for the nickname, he eventually adopted it with slight changes as his official last name.[3]

The West Nile Province was a poor region, and offered few occupation opportunities for young men.[6] As a result, most of Gowon's friends joined the King's African Rifles when they finished primary school. In contrast, he opted to attend the junior high school, and subsequently an agricultural college. There, Gowon learned how to drive a tractor, and used his new skills to set up his own farm. This endeavor yielded little monetary gains, so Gowon decided to switch to working on a prison farm producing cotton in 1964.[12][11] He enjoyed the work, and a British overseer taught him to repair the farm's machinery. Gowon later described this time as the happiest of his life.[11]

Military service

Early career and invasion of 1972

Gowon left the prisons service in 1968, and enlisted in the military. This decision partially stemmed from the changed political situation in Uganda. The country had become independent in 1962, and the Ugandan King's African Rifles units had been transformed into the Uganda Army. At the same time, politicians began to conspire and struggle for power, backed by the country's numerous tribal groups. By the late 1960s, the main opposing factions were led by Army chief of staff Idi Amin (mainly supported by the West Nile tribes) and President Milton Obote (mainly backed by the Acholi and Langi). In order to secure the power over the Uganda Army, both launched extensive recruitment drives to enlist as many members of their own respective tribal groups as possible.[12] As a result, military service offered great social and financial rewards which appealed to Gowon despite his disinterest in warfare.[13]

At first, Gowon was sent to a boot camp north of Kampala, Uganda's capital, where Amin was training a new elite unit. Obote considered this new unit a potential threat, however, and ordered its disbandment. As result, Gowon was reassigned to the military police,[14] and later to the paratroopers trained by Israeli experts.[15] At some point after 1969, he was among those sent to Greece for a course in commando tactics.[12][15] In 1971, Amin launched a coup d'état and installed himself as President, though Obote found refuge in Tanzania. Amin's military dictatorship promptly purged the army of all those who were believed loyal to Obote, including most Acholi and Langi. The vacant leadership positions were then filled with soldiers who were loyal to Amin and usually from the West Nile Province.[16] Gowon returned to Uganda after the coup's conclusion, and was promoted to major and appointed second-in-command of the Simba Battalion, stationed at Mbarara. Another Ugandan ex-officer later commented that Gowon was not prepared for such a promotion, and was just appointed because he belonged to Amin's own tribal group and religion. With the President as his personal patron, Gowon held great power over the Simba Battalion, probably more than the official commanding officer, Colonel Ali Fadhul.[17]

"Some men will themselves to power. Gowon, it seemed, had just happened into it."

—Researcher Andrew Rice about Gowon's rise in the ranks of the Uganda Army[18]

Despite his inexperience, Gowon won some respect as second-in-command of the Simba Battalion, and was regarded as more polite and humane than other military officers who abused their power. While he was stationed at Mbarara, the Simba Battalion carried out numerous massacres of Acholi and Langi; Gowon later claimed that he knew nothing of any mass murders.[19] On 17 September 1972, rebels loyal to Obote launched an invasion of Uganda from Tanzania.[20] As Colonel Fadhul went missing amid the attack's early stages, Gowon was left in command of the Simba Battalion, and organized a counter-attack against a rebel column of 350 fighters. This counter-attack completely overwhelmed the rebels, most of whom were killed or captured. After Obote's invasion had been repelled, Amin ordered a purge of any possible rebel supporters throughout Uganda. One of Gowon's subordinates, Nasur Gille, later testified under disputed circumstances[lower-alpha 4] that Gowon ordered and organized the political murders in Mbarara.[22][21] It is known that the commander had good connections to at least some members of the State Research Bureau, Amin's secret police organisation, and some victims of the purges as well as their families believe that Gowon ordered their deaths.[23][24] Despite this, several residents of Mbarara argued that Gowon actually saved many lives during the mass killings. They later recalled that people had been marked for execution, but been freed on Gowon's orders.[25][24] When questioned about his involvement in some political murders, the commander later told that "Any commanding officer who defended them [i.e. the victims]... When you defend, you become a collaborator", meaning one would in turn be marked for death.[24]

Rise in the ranks

Gowon's reputation improved due to his role in defeating Obote's invasion, and he consequently rose in the ranks. When Amin ordered the expulsion of Asians from Uganda, Gowon was one of those responsible for redistributing the properties of about 40,000 deported Indian businessmen. This job was not just profitable and made him quite wealthy, but helped him to forge political connections.[19] He proved extremely adapt at politics, and gradually gained a reputation as "ruthless infighter" in the Uganda Army who would manipulate others to get his way.[26] Nevertheless, Gowon almost fell from power after the Arube uprising, a coup attempt against Amin in 1974. An unidentified person told the President that Gowon was secretly a Christian which was enough to warrant suspicions about him being a supporter of the coup attempt.[27][lower-alpha 5] He was placed under house arrest, but Army Chief of Staff Mustafa Adrisi intervened on his behalf, allowing Gowon to be flown to Libya for medical treatment of a stomach ailment. In this way, he avoided the worst purges, and upon returning was even promoted to commander of a unit in eastern Uganda.[18] Over the following years, Gowon rose to lieutenant colonel, colonel, and brigadier general.[21] By 1976, he commanded the Eastern Brigade.[29][5]

"Amin, I must leave my work. I may die like Gowon is going to die. These Nubians are deceiving you."

—Mustafa Adrisi begging for President Idi Amin to spare Gowon's life[18]

Around 1976, Gowon was again accused of treason as result of political conspiracies among Amin's inner circles. A rival alleged that he was in contact with anti-Amin rebels in Tanzania. He was arrested by the State Research Bureau,[29] and, alongside his protector Adrisi, brought into the President's bureau. There, Amin told them that more evidence had surfaced about Gowon's support for the 1974 coup attempt,[18] and had him ordered out of sight. Gowon believed that he was going to be executed.[29] Adrisi fell on his knees[30] and begged the President to reconsider, claiming that the entire affair was engineered by a clique of Nubians. Amin finally relented,[18] and ordered Gowon back into the room. He then got everyone a cup of tea and told Gowon that he was spared. Regardless, the President also threatened that if the general was accused one more time of involvement in the 1974 coup, he would be executed.[18][30]

Despite this incident, Gowon remained one of Amin's most trusted followers. The general would spy for the President on other officers, while trying to remove his own rivals.[31][30] His military rivals referred to him as "snake" as a commentary on his apparent deft political abilities which facilitated his rise in the ranks.[32] His political skills did not endear him to his subordinates who held little respect for him. They regarded Gowon as an "uneducated rube", and promoted far above his station. He was even derogatorily nicknamed "the tractor driver" by soldiers due to his past as a farmer.[33] Some officers also disliked Gowon due to his tendency to circumvent them and deal with the lower ranks directly.[24] In contrast, he was popular among the people of his birthplace, Ladonga, because he paid school tuition for local children, and built a primary school and a medical clinic.[4]

In early 1978, Adrisi was almost killed in a car accident that was suspected to be actually an assassination attempt. Amin consequently purged several of Adrisi's followers from the government, including Uganda Army Chief of Staff Isaac Lumago.[34][26] Gowon was made acting Army Chief of Staff, and promoted to major general on 8 May 1978.[35] He was formally appointed as Lumago's successor[36][37][38] in June.[39] By this point, the repeated purges had reduced Amin's inner circle to a small number of officers. Gowon's appointment was mostly owed to the fact that he was regarded as loyal to Amin, and lacked a power base in the military to threaten the President.[40][41] After becoming chief of staff, one reporter described him as the "second-most powerful man in the country".[42]

As chief of staff, Gowon was tasked by Amin to carry out another purge in the Uganda Army's upper ranks. He disempowered the heads of two intelligence services, and also moved against his long-time rival General Moses Ali.[26] Ali was removed from his posts in April 1978, and almost killed by hitmen when he went into self-imposed exile in his home town in West Nile. He consequently blamed Gowon for these events.[31][26][43] Although Gowon had thus risen to one of Amin's closest allies and proven to be competent in politics, he was not qualified as head of the military, and lacked training in basic strategy.[33][44] In September 1978 Amin, in response to international criticisms of his regime, announced the creation of a human rights committee "charged with the duty of explaining Uganda's position abroad". Gowon was made a member of the body, though subsequent events prevented it from performing any work.[32]

The Uganda–Tanzania War, dismissal, and desertion

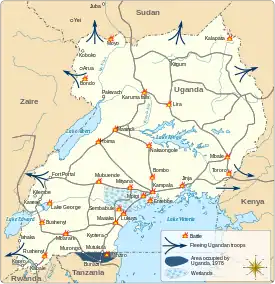

In late 1978, tensions between Uganda and Tanzania culminated in open warfare. The exact circumstances of the conflict's outbreak remain unclear,[45] but President Amin ordered an invasion of northwestern Tanzania on 30 October 1978. Gowon was put in charge of about 3,000 soldiers to carry out the operation which initially went well. The Tanzanian border guards were overwhelmed and the Kagera salient occupied, whereupon the Ugandan troops launched a spree of plundering, rape, and murder. Gowon joined the looting, and reportedly demoted an Ugandan captain when the latter refused to hand over a stolen tractor to him.[lower-alpha 6] After the Uganda Army blew up a bridge across the Kagera river, Gowon believed that he had made a Tanzanian counter-offensive impossible and thereby won the war. This turned out to be a catastrophic miscalculation, as the Tanzania People's Defence Force (TPDF) counter-attacked using a pontoon bridge, routing the Ugandans.[40] Thereafter, Tanzania began preparing a counter-invasion of Uganda, but Gowon and other high-ranking commanders ignored warnings by subordinate officers about an impending Tanzanian offensive.[46] Colonel Bernard Rwehururu in particular accused Gowon of gross incompetence, recalling an occasion when he showed the Chief of Staff a map with possible Tanzanian invasion routes. Gowon was allegedly unimpressed, and replied "What's wrong with you? You are always thinking of maps. Do you fight with maps?"[47] Another officer stated that the Chief of Staff lied to the President about the military situation, and ignored messages by frontline commanders.[48] Other unidentified officers alleged that Gowon and other Ugandan high-ranking commanders focused more on "their petty feuds" than on the war.[49]

One of the greatest problems for the Uganda Army was its lack of artillery, while the Tanzanians had ample access to Katyusha rocket launchers. Gowon put off this issue until another Ugandan general urged him to finally do something about it. Gowon asked Amin to buy artillery abroad, but the man who was entrusted this task simply pocketed the money.[40] The TPDF invaded on 21 January 1979, and defeated the Uganda Army in a series of battles.[47] Amin consequently dispatched Gowon to the frontlines which was "widely interpreted as a punishment".[50] Eventually, Amin's Libyan ally Muammar Gaddafi intervened by sending an expeditionary force,[47] whereupon a combined Ugandan-Libyan counter-offensive was launched against Lukaya on 10 March 1979. The battle turned against the Ugandans on 11 March, as the TPDF launched a successful counter-attack. In an attempt to strengthen morale, Gowon and General Isaac Maliyamungu joined their troops on the front line at Lukaya. For unknown reasons, the positions the two men took were frequently subject to sudden, intense rocket fire. Ugandan junior officers tried to convince their men that the Tanzanians were probably aware of the generals' presence and were targeting them with precise bombardments. The Ugandan troops nonetheless felt that Maliyamungu and Gowon were harbingers of misfortune and nicknamed them bisirani, or "bad omen". The leading Ugandan commander at Lukaya, Godwin Sule, realised the generals were not having a positive effect and asked them to leave the front.[51]

According to an unidentified "high Ugandan official" who was in exile in Nairobi at the time, Gowon and other officers unsuccessfully urged Amin to step down as President after the Battle of Lukaya.[52] Soon after, a Libyan officer visited Gowon's headquarters, and relayed that Amin had fired him. The Libyan then mounted a tank and addressed the Ugandan soldiers present, telling them that Gowon had betrayed them to the Tanzanians.[47] The soldiers were enraged, and wanted to murder their former Chief of Staff,[53] but Gowon claimed that he intended to muster reinforcements. Using this excuse,[54] he fled to Kampala and from there to Wile Nile on a motorcycle. His troops believed that he had deserted,[47] prompting one of them to comment in an interview with the Drum magazine that "Our recent chief of staff, Major General Gowon, has disappeared. Only hell knows where he is."[55] He was succeeded as Chief of Staff by Ali Fadhul.[52]

Exile in Zaire and return to Uganda

When Gowon arrived in Arua, West Nile, he initially laid low and planned his possible exile. However, he eventually chanced upon a detachment of Ugandan soldiers who knew him.[54] These troopers arrested him as traitor, and confiscated his wealth.[56][lower-alpha 7] By chance, Gowon's old ally Mustafa Adrisi visited Arua shortly after his arrest, and ordered his release.[47] Adrisi told Gowon that he should flee Uganda as soon as possible, and the former Chief of Staff followed this recommendation.[57] He was unsure whether to go into exile in Zaire or Sudan, but chose the former because most Amin loyalists – who intended to kill him – were fleeing to Sudan.[58] Gowon initially found refuge with Catholic missionaries.[57] Meanwhile, Amin's regime collapsed as the Tanzanians and their Ugandan rebel allies occupied Kampala, prompting most Uganda Army loyalists to flee into Sudan and Zaire.[lower-alpha 8] Zairean dictator Mobutu Sese Seko allowed the Ugandan exiles, including Gowon, to stay in his country. As many believed that Gowon had actually been bribed by the Tanzanians and lost the war on purpose, he became a persona non grata among the Ugandan exiles and thus excluded from plans by Amin loyalists to launch a rebellion to regain power. Gowon was actually pleased about this, as he had no interest in resuming fighting.[57][59]

Instead, Gowon focused on building a new life in Zaire,[57] taking up residency in Kisangani.[60] By befriending a Zairean customs officer, he had transported some trucks out of Uganda and would subsequently rent them out.[57] He was also involved in smuggling, and eventually made enough money to buy a house in Bunia where he was joined by two of his wives.[59] At the same time, Uganda descended into civil war which resulted in Yoweri Museveni's rise to presidency in 1986. Museveni's government focused on national reconstruction, and offered reconciliation to Amin's former followers. Gowon took up this offer in 1994. He returned to Uganda with 25 other ex-officers, hundreds of dependants, and over ten thousand civilian refugees.[57][59] Museveni personally welcomed Gowon back to Uganda, and the two even laughingly reminisced about the 1972 invasion during which they had fought each other (Museveni had been part of Obote's rebel alliance at the time). Mbarara threw a "huge party" in Gowon's honor.[57] The Ugandan government rented him a house[61] in Ntinda,[42][62] and granted him a stipend.[62] Grateful for this treatment, Gowon subsequently supported Museveni, and made speeches in his favor during the 1996 Ugandan presidential election.[61]

The former Chief of Staff also founded "Good Hope"[63] and "Alternatives to Violence", nonprofit organizations to help ex-combatants to find civilian jobs.[25] The Ugandan government promised Gowon funds to set up companies in which the ex-rebels could be employed, but the money never materialised. Over the next years, his stipend was paid ever less regularly, and Gowon was no longer able to pay his rent. He was evicted from his Ntinda residence, and had to relocate to live in a bicycle shop run by one of his sons. Broke and without a job, he spent most his time in the Slow Boat Pub.[63] At some point, Gowon became the leader of a Uganda Army veterans association.[64]

Trial

Gowon lived in retirement until 2001, when he was arrested by the Ugandan police for the murder of county chief Eliphaz Laki. According to the testimony of two former subordinates of Gowon, Laki had been murdered on his orders during the purges following the 1972 invasion. The former Chief of Staff disputed any knowledge of or involvement in Laki's death, but was placed in the Luzira Maximum Security Prison and put on trial.[65] Gowon faced the death sentence if convicted of the murder.[3] His trial generated much publicity in Uganda, as most crimes during Amin's regime remained unresolved due to lack of evidence and lack of interest in prosecuting them on the side of the Ugandan government which wants to maintain communal peace.[25] The prosecutors, the families of victims, and reporters saw Gowon's trial as the last chance to finally address the injustices of Amin's regime which had killed between 100,000 and 300,000 people, as the majority of the perpetrators were already quite old.[66][67] Lead prosecutor Simon Byabakama Mugenyi stated that "It's like our Nuremberg Trial."[22] Others, mostly people from West Nile, saw Gowon as victim of political conspiracies.[68] Gowon believed that his old rival, Moses Ali, was behind his trial. By then, Ali had risen to minister of internal affairs in Museveni's government and was quite influential. At some point, the minister allegedly visited Luzira Prison just to enjoy seeing Gowon imprisoned; Ali denied all of this, once stating that he "did not even know [that Gowon] was arrested" until reading of it in the newspapers.[43] In general, prison life was difficult for Gowon and he lost more than thirty pounds while incarcerated. However, he had few problems with most other prisoners at Luzira and even developed a friendship with one of his former enemies who also served a prison term. However, he had a tense relationship with those prisoners who had formerly served alongside him in the Uganda Army. The hostility between him and his ex-superior Ali Fadhul was so intense that prison authorities had to keep the two separate.[69] The former Chief of Staff maintained his innocence during the entire trial,[70][24] stating on one occasion that "These people were civilians. They could not have been killed. This is what I know."[71]

Gowon's former subordinates had confessed before the trial that they had murdered Laki on Gowon's direct order, but the reliability of their confessions was questioned during the trial. They had told the police about Gowon's order because they had already been arrested on charges of murder, hoping to be treated leniently by indicting Gowon. When this did not come to pass, the purported witnesses recanted their confessions.[72] As the prosecutors attempted to gather more and firmer evidence for Gowon's guilt, the trial dragged on for almost a year.[73] The trial resulted in tensions among Gowon's family. When well-wishers donated money for his defense, one of his sons absconded with it. The former Chief of Staff then tried to hire an attorney, Caleb Alaka, by promising him a house, but Gowon's wife promptly sued him. She argued that the house in question was rightfully hers. In the end, Alaka still took the case out of respect and pity for the former Chief of Staff.[62] Early in the trial, one person offered Gowon's family and the defense attorney to speak out in favor of the former Chief of Staff in return for a bribe; the family had to refuse, as they were still broke.[74][lower-alpha 9]

Though Laki's son had managed to gather evidence which suggested that Gowon was guilty, it was regarded as inadmissible by the judge.[23] The defense attempted to discredit other evidence which had been found by a private investigator who died while the trial was still ongoing, arguing that the latter had died of a mental disorder although he had in fact died of HIV/AIDS.[75] In the middle of the trial, defense attorney Caleb Alaka simply disappeared; he later resurfaced in Western Nile, where he had taken a job representing a rebel group which had signed a peace deal with the Ugandan government. Five months later he rejoined Gowon's trial,[76] only to disappear again in February 2003, this time for good.[77] For lack of firm evidence, the judge acquitted Gowon and the two other defendants on 25 September 2003.[78] His release was celebrated by his family and sympathizers, mostly from West Nile, while Laki's family and sympathizers, mostly from southern Uganda, decried it as injustice. Some even spread conspiracy theories according to which the government had installed the judge, a Muslim, because he would support Gowon and his co-defendants.[79] The former Chief of Staff regarded the verdict as vindication of his innocence.[80]

Later life

Following his release, Gowon resumed his work in the veterans association, and consequently advocated for a greater unity among ex-combatants of West Nile origin.[64] However, he struggled to pay the legal bills of the trial.[81] By 2005, he was spending most of his time at Arua where he still possessed a house,[82] and had joined a class action lawsuit against several banks that had frozen assets of Amin-era officials worth 50 million dollars.[83]

Personal life

Academic Andrew Rice described Gowon as a "simple man" who is "cheerful by disposition", and easily makes friends.[84] He has 28 children by four different wives, and 22 grandchildren.[25] Gowon is fluent in Swahili, and he understands a little English.[85] He is a Muslim.[86]

Notes

- ↑ also known as Yusuf Gowan[1] and Yufu Gowon[2]

- ↑ George Ivan Smith falsely stated that Gown was born in southern Sudan.[5]

- ↑ The Nubians of Uganda were "an extremely fluid category".[8] They are often portrayed as descendants of Emin Pasha's mostly Muslim soldiers who fled to Uganda after being defeated by Mahdist Sudanese forces in the 1880s. Regarded as martial people, they were consequently recruited into British colonial units; as a result, West Nile people who wanted to join the military often claimed to be Nubians. This led to the paradoxical situation that the Nubians were both "detribalised" yet had also a distinct identity intimately linked to the West Nile region, to Islam, and to military service.[9]

- ↑ Gille claimed that his testimony was coerced.[21]

- ↑ Rice initially stated that Gowon was accused in the involvement of a 1973 coup attempt,[28] but corrected the date to 1974 in his later account of the events.[27]

- ↑ Gowon admitted that there had been an incident about a tractor, though claimed that he commandeered it because the captain did not know how to drive it.[40]

- ↑ Gowon was known for his large collection of cars which he lost amid the collapse of Amin's regime. By 2001, he no longer possessed any motor vehicles. While in exile, Idi Amin made fun of this, laughingly commenting "I hear Gowon, a whole major general, walks from his house in Ntinda to town and has no car."[42]

- ↑ After Amin's fall from power, rival tribes exacted revenge from the West Nile peoples who had prospered under his dictatorship. Gowon's wider family and associates were among those negatively affected. Militants came to Ladonga, where they destroyed Gowon's mansion, the clinic, and the school, while killing several locals. The community subsequently became marginalized and poor.[4]

- ↑ Upon his arrest, the Ugandan government cut off Gowon's stipend.[62]

References

Citations

- ↑ Rwehururu 2002, p. 96.

- ↑ Decalo 2019, The Collapse of a Dictator.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rice 2003a, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Rice 2003b, p. 8.

- 1 2 Smith 1980, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 Rice 2003a, p. 5.

- ↑ Rice 2009, p. 152.

- ↑ Nugent 2012, p. 233.

- ↑ Leopold 2005, p. 60.

- 1 2 3 Rice 2009, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 Rice 2009, p. 159.

- 1 2 3 Rice 2003a, p. 6.

- ↑ Rice 2009, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Rice 2009, pp. 160–161.

- 1 2 Rice 2009, p. 162.

- ↑ Rice 2003a, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Rice 2003a, pp. 7–8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rice 2003a, p. 10.

- 1 2 Rice 2003a, p. 8.

- ↑ Rice 2003a, pp. 8–9.

- 1 2 3 Rice 2003a, p. 9.

- 1 2 Rice 2004a, p. 4.

- 1 2 Rice 2004a, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rice 2004b, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 4 Rice 2003a, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Rice 2009, p. 198.

- 1 2 Rice 2009, p. 195.

- ↑ Rice 2003a, pp. 9–10.

- 1 2 3 Rice 2009, p. 197.

- 1 2 3 Rice 2009, pp. 197–198.

- 1 2 Rice 2003a, pp. 10–11.

- 1 2 Lowman 2020, p. 176.

- 1 2 Rice 2003a, pp. 4, 11.

- ↑ Otunnu 2016, p. 313.

- ↑ "Ministerial Appointment and Military Promotions in Uganda". Summary of World Broadcasts: Non-Arab Africa. 8 May 1978.

- ↑ Rice 2003a, pp. 3–4, 11.

- ↑ Clement Aluma; Felix Warom Okello (9 May 2012). "Maj. Gen. Isaac Lumago dies at Arua referral hospital". Daily Monitor. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ Omara-Otunnu 1987, p. 140.

- ↑ "Uganda : Mutiny a minor manifestation of discontent". To the Point International. Vol. 5, no. 41. 1978. p. 55.

- 1 2 3 4 Rice 2003a, p. 11.

- ↑ Rice 2009, p. 199.

- 1 2 3 Rice 2003a, p. 1.

- 1 2 Carol Natukunda (24 April 2013). "Amin played Moses Ali against Yusuf Gowon". New Vision. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ↑ Rice 2009, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Roberts 2017, p. 156.

- ↑ Rice 2003a, pp. 11–12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rice 2003a, p. 12.

- ↑ Faustin Mugabe (17 April 2016). "Uganda annexes Tanzanian territory after Kagera Bridge victory". Daily Monitor. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ Rice 2009, p. 203.

- ↑ Rice 2009, p. 204.

- ↑ Rwehururu 2002, p. 125.

- 1 2 John Daimon (6 April 1979). "Libyan Troops Supporting Amin Said to Flee Kampala, Leaving It Defenseless". The New York Times. p. 9. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ↑ Rice 2003a, p. 4.

- 1 2 Rice 2009, p. 205.

- ↑ Seftel 2010, p. 231.

- ↑ Rice 2009, pp. 206–207.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rice 2003a, p. 13.

- ↑ Rice 2009, p. 207.

- 1 2 3 Rice 2009, p. 136.

- ↑ Magembe, Muwonge (7 March 2016). "The pain Idi Amin's friend suffered for 20 years in exile". New Vision. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- 1 2 Rice 2003a, pp. 13–14.

- 1 2 3 4 Rice 2004b, p. 4.

- 1 2 Rice 2009, p. 138.

- 1 2 Amandu, Rimiliah (11 May 2018). "Arua veteran decry poor mobilization and disunity among members". West Nile Web. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ Rice 2003a, pp. 1–3, 14.

- ↑ Rice 2003a, pp. 2, 14.

- ↑ Rice 2004a, pp. 4–6.

- ↑ Rice 2004b, pp. 4–6.

- ↑ Rice 2009, pp. 135, 322.

- ↑ Rice 2004a, p. 3.

- ↑ Rice 2003a, p. 14.

- ↑ Rice 2004a, p. 7.

- ↑ Rice 2004a, p. 8.

- ↑ Rice 2004a, p. 11.

- ↑ Rice 2004b, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Rice 2004b, p. 9.

- ↑ Rice 2004b, p. 12.

- ↑ Rice 2004b, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Rice 2004b, p. 13.

- ↑ Rice 2004b, p. 16.

- ↑ Rice 2009, p. 284.

- ↑ Rice 2009, pp. 283–285.

- ↑ Rice 2009, pp. 285–286.

- ↑ Rice 2003a, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Rice 2004a, p. 9.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 50.

Works cited

- Avirgan, Tony; Honey, Martha (1983). War in Uganda: The Legacy of Idi Amin. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Publishing House. ISBN 978-9976-1-0056-3.

- Cooper, Tom; Fontanellaz, Adrien (2015). Wars and Insurgencies of Uganda 1971–1994. Solihull: Helion & Company Limited. ISBN 978-1-910294-55-0.

- Decalo, Samuel (2019). Psychoses Of Power: African Personal Dictatorships. Routledge. ISBN 9781000308501.

- Leopold, Mark (2005). Inside West Nile. Violence, History & Representation on an African Frontier. Oxford: James Currey. ISBN 0-85255-941-0.

- Lowman, Thomas James (2020). Beyond Idi Amin: Causes and Drivers of Political Violence in Uganda, 1971-1979 (PDF) (PhD). Durham University. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Nugent, Paul (2012) [1st pub. 2004]. Africa since Independence (2nd ed.). London: Red Globe Press. ISBN 978-0-230-27288-0.

- Rice, Andrew (20 August 2003). "The General" (PDF). Institute of Current World Affairs Letters. AR (12).

- Rice, Andrew (1 September 2003). "Thin" (PDF). Institute of Current World Affairs Letters. AR (13).

- Rice, Andrew (1 March 2004). "The Trial" (PDF). Institute of Current World Affairs Letters. AR (18).

- Rice, Andrew (1 April 2004). "The Trial" (PDF). Institute of Current World Affairs Letters. AR (19).

- Rice, Andrew (2009). The Teeth May Smile But the Heart Does Not Forget: Murder and Memory in Uganda. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-7965-4.

- Roberts, George (2017). "The Uganda–Tanzania War, the fall of Idi Amin, and the failure of African diplomacy, 1978–1979". In Anderson, David M.; Rolandsen, Øystein H. (eds.). Politics and Violence in Eastern Africa: The Struggles of Emerging States. London: Routledge. pp. 154–171. ISBN 978-1-317-53952-0.

- Rwehururu, Bernard (2002). Cross to the Gun. Kampala: Monitor. OCLC 50243051.

- Omara-Otunnu, Amii (1987). Politics and the Military in Uganda, 1890–1985. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-18738-6.

- Otunnu, Ogenga (2016). Crisis of Legitimacy and Political Violence in Uganda, 1890 to 1979. Chicago: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-319-33155-3.

- Seftel, Adam, ed. (2010) [1st pub. 1994]. Uganda: The Bloodstained Pearl of Africa and Its Struggle for Peace. From the Pages of Drum. Kampala: Fountain Publishers. ISBN 978-9970-02-036-2.

- Smith, George Ivan (1980). Ghosts of Kampala. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0060140274.