The Zanja Madre (Spanish: [ˈsaŋxa ˈmaðɾe], "Mother Trench") is the original aqueduct that brought water to the Pueblo de Los Angeles from the Río Porciúncula (Los Angeles River). The original open, earthen ditch, or zanja was completed by community laborers within a month of founding the pueblo.[lower-alpha 1] This water system was used for both domestic uses and irrigation to fields west of town. The main zanja ultimately fed eight branch zanjas.[1] This availability of water was essential to the survival and growth of the community founded here. Brick conduits 3 to 3.5 feet (0.91 to 1.07 m) in diameter were built to improve the system after 1884. Eventually the system did not supply enough water to keep pace with population growth and irrigation demand. The system was abandoned by 1904 though portions were still used for storm water purposes.[2] It was maintained by the Zanjero of Los Angeles.

Origins

The Pueblo de Los Angeles was an official settlement of Spain. They had three types of settlements in Alta California: presidio (military), mission (religious) and pueblo (civil). The pueblos would provide the commercial and agricultural needs of the military as an alternative to the missions. Governor Felipe de Neve took the assignment of creating this settlement very seriously and had elaborate plans drawn up outlining the details of its infrastructure. The plan included a governmental directive for the provision of water to be delivered to the settlement, stating, "there should be examined all the lands which may receive the benefit of irrigation, marking the place most proper to divert the water, so that it may be allotted to the largest portion of lands."[3] It was also directed that the pueblo be placed on moderately elevated ground so that all the agricultural lands benefiting from the irrigation could be overlooked. This would mean that the supply head would have to be at yet higher ground.

The Zanja Madre was placed close to present-day Broadway at the foot of the Elysian Hills by the river. An earth and brush dam, called a toma, was created to pool up the water into the ditch which then ran along an elevated slope down to the pueblo after which it was split into multiple ditches which ran to the various portions of lowland.[4] A large water wheel, constructed in the 1850s, took water up to the Zanja Madre and onto the main brick reservoir that was located in what is now the Plaza at the end of Olvera Street. The wheel was susceptible to damage from floods. The toma was washed away several times before a wooden one was built in its place.[5]

Later improvements

The soft, sandy tunnel collapsed several times and attempts were made to repair it with brick lining, but the whole aqueduct was abandoned in 1884 after a flood tore out the wooden dam. It had already been realized since 1878 that several improvements would have to be done to the zanja systems. Some of this included conversion of the smaller ditches to pipelines while larger areas would be concrete. After this last failure the earthen toma and open ditch were put back into service while more elaborate plans were being made.

In 1888 the city planned to put pipe in most of the existing zanjas, but budgetary shortfalls did not allow the work to be finished. The tunnel at the headwater of the Zanja Madre was reconstructed and much of the conduit was either brick or concrete lined. By 1893 there ended up some 50 mi (80 km) of zanjas in the city and another 40 mi (64 km) of zanjas outside the city limit. Over the years the portion of the Zanja Madre that passed around the north edge of the River Train Yard was realigned again and again until railroad construction eventually demolished most of the conduits as the city built newer types of water systems.

Archaeological finds

At least 18 segments of the Los Angeles Zanja system, including various portions of the Zanja Madre, have been documented as they have been uncovered during construction projects over the years. The resource was first formally documented by archaeologists in 1978 when archaeologist Julia Costello discovered a portion of the Zanja Madre during construction of the Plaza de Dolores.[7]

In 2000 two people dug up a section of the Zanja on the steep slope near a Broadway parking garage and were credited by the L.A. Weekly and Los Angeles Times as having rediscovered the Zanja. Later, archaeologists overseeing site operations near the MTA Gold Line studied the portions of uncovered brick conduit. They expected to find more portions along the line near the River Yard, but there were no discoveries. It was generally supposed that the Zanja had been destroyed during railroad yard construction over the years. Since it was private property, no archaeological surveys were made.[8]

In 2005 MTA construction crews uncovered unexpected sections of the brick Zanja Madre. Archaeologists were brought in to evaluate the finds, most of which were red-brick, penstock-sized aqueducts. Now serious studies and documentation have begun in order to have the Zanja Madre routes put onto historical registers.[9]

In 2014 excavation for the foundation of the Blossom Plaza project on North Broadway discovered a 100-foot-long section (30 m).[10] The careless and rushed removal of a 40-foot portion (12 m) of the Zanja Madre to allow the development to continue without delay has been criticized in the editorial pages of the Daily News[11] and by KCET Departures.[12] The brick section was destroyed when moved.

At least three exposed segments of the Zanja Madre survive on publicly-owned land. They include a segment owned by Los Angeles County and located next to the Gold Line tracks adjacent to Los Angeles State Historic Park, and two City-owned segments located within buildings at Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument.[13]

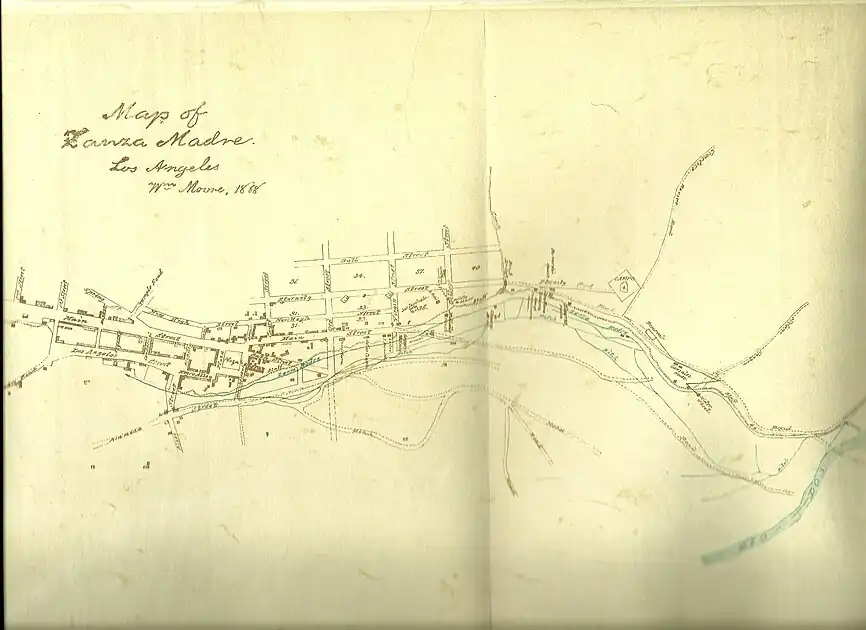

A leather book with a hand-drawn map from the city survey records dated to 1887 identifies the location where newly unearthed brick and mortar pipe was found according to the City Surveyor, Tony Pratt.[14]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The word zanjero was the 19th century title of a municipal worker who had charge of the water system in Los Angeles.

References

- ↑ Phillips, George Harwood (August 1, 1980). "Indians in Los Angeles, 1781-1875: Economic Integration, Social Disintegration". Pacific Historical Review. 49 (3): 427–451. doi:10.2307/3638564. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3638564.

- ↑ "Zanja Madre, Los Angeles County". Cogstone Resource Management Inc. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014.

- ↑ Irrigation Development: History, Customs, Laws, and Administrative Systems Relating to Irrigation, Water-courses, and Waters in France, Italy, and Spain. The Introductory Part of the Report of the State Engineer of California, on Irrigation and the Irrigation Question. Vol. 2. James J. Ayers, Superintendent state printing. 1886.

- ↑ "Los Angeles County History – An Illustrated History of Southern California". The Water Supply. CalArchives4u.com. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company. 1890. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ↑ Zanja No. 3: Brick Culvert HAER No. CA-50 (PDF). National Park Service. 1986. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 2, 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Christine Sterling. Olvera Street: El Pueblo de Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los Angeles: Its History and Restoration. Self-published, 1947

- ↑ https://scahome.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/16_Beherec_final.pdf

- ↑ Maese, Kathryn (May 8, 2000). "Hitting the Mother Load". Los Angeles Downtown News. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016.

- ↑ Pool, Bob (March 31, 2005). "Historic Aqueduct in L.A. to Be Buried". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016.

- ↑ Pool, Bob (April 21, 2014). "Workers discover part of L.A.'s first municipal water system". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Editorial: Preserve the Zanja Madre in Place". Los Angeles Daily News. April 29, 2014. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016.

- ↑ Jao, Carren (May 2, 2014). "Are We Doing All We Can for the Zanja Madre?". Departures. KCET. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015.

- ↑ https://scahome.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/16_Beherec_final.pdf

- ↑ Pool, Bob (April 25, 2014). "Field guide written by surveyor in 1887 pointed to L.A.'s 'Mother Ditch'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014.

External links

- "The History and Archaeology of the Zanja Madre, Los Angeles, California" (PDF). Cogstone Resource Management, Inc. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2007.

Contains valuable bibliography, Prepared for the MTA under contract to UltraSystems Environmental

- "Departures slideshow of the Zanja Madre". KCET.