| Realgar | |

|---|---|

Realgar crystals, Royal Reward Mine, King County, Washington, US | |

| General | |

| Category | Sulfide mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | As4S4 or AsS |

| IMA symbol | Rlg[1] |

| Strunz classification | 2.FA.15a |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Crystal class | Prismatic (2/m) (same H-M symbol) |

| Space group | P21/n (no. 14) |

| Unit cell | a = 9.325(3) Å b = 13.571(5) Å c = 6.587(3) Å β = 106.43°; Z = 16 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Red to yellow-orange; in polished section, pale gray, with abundant yellow to red internal reflections |

| Crystal habit | Prismatic striated crystals; more commonly massive, coarse to fine granular, or as incrustations |

| Twinning | Contact twins on {100} |

| Cleavage | Good on {010}; less so on {101}, {100}, {120}, and {110} |

| Tenacity | Sectile, slightly brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 1.5–2 |

| Luster | Resinous to greasy |

| Streak | Red-orange to red |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent |

| Specific gravity | 3.56 |

| Optical properties | Biaxial (-) |

| Refractive index | nα = 2.538 nβ = 2.684 nγ = 2.704 |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.166 |

| Pleochroism | Nearly colorless to pale golden yellow |

| 2V angle | 40° |

| Dispersion | r > v, very strong |

| Other characteristics | Toxic and carcinogenic. Disintegrates on long exposure to light to a powder composed of pararealgar or arsenolite and orpiment. |

| References | [2][3][4][5][6] |

Realgar (/riˈælɡɑːr, -ɡər/ ree-AL-gar, -gər), also known as "ruby sulphur" or "ruby of arsenic", is an arsenic sulfide mineral with the chemical formula α-As4S4. It is a soft, sectile mineral occurring in monoclinic crystals, or in granular, compact, or powdery form, often in association with the related mineral, orpiment (As2S3). It is orange-red in color, melts at 320 °C, and burns with a bluish flame releasing fumes of arsenic and sulfur. Realgar is soft with a Mohs hardness of 1.5 to 2 and has a specific gravity of 3.5. Its streak is orange colored. It is trimorphous with pararealgar and bonazziite.[2]

Etymology

Its name comes from the Arabic rahj al-ġār (رهج الغار [rahdʒ ʔlɣaːr] ⓘ, "powder of the mine"), via Medieval Latin, and its earliest record in English is in the 1390s.[7][8][9]

Uses

Realgar is a minor ore of arsenic extracted in China, Peru, and the Philippines. [10]

Historical uses

Realgar was used by firework manufacturers to create the color white in fireworks prior to the availability of powdered metals such as aluminium, magnesium and titanium. It is still used in combination with potassium chlorate to make a contact explosive known as "red explosive" for some types of torpedoes and other novelty exploding fireworks branded as 'cracker balls', as well in the cores of some types of crackling stars.

Realgar is toxic. It was sometimes used to kill weeds, insects, and rodents,[11] even though more effective arsenic-based anti-pest agents are available such as cacodylic acid, (CH3)2As(O)OH, an organoarsenic compound used as herbicide and also to kill ants and mice.

Realgar was commonly used in leather manufacturing to remove hair from animal pelts. Because it is a known carcinogen and an arsenic poison, and because substitutes are available, it is rarely used today for this purpose.

The ancient Greeks, who called realgar σανδαράκη (sandarákē), understood that it was poisonous. From this, realgar has also historically been known in English as sandarac.

Realgar was also used by Ancient Greek apothecaries to make a medicine known as "bull's blood".[12] The Greek physician Nicander described a death by "bull's blood", which matches the known effects of arsenic poisoning.[12] Bull's blood is the poison that is said to have been used by Themistocles and Midas for suicide.[12]

The Chinese name for realgar is 雄黃 (Mandarin xiónghuáng), literally 'masculine yellow', as opposed to orpiment which is 'feminine yellow'.[13]

Realgar was, along with orpiment, traded in the Roman Empire and was used as a red paint pigment. Early occurrences of realgar as a red paint pigment are known for works of art from China, India, Central Asia, and Egypt. It was used in European fine-art painting during the Renaissance era, a use which died out by the 18th century.[14] It was also used as medicine. Other traditional uses include manufacturing lead shot, printing, and dyeing calico cloth. It was used to poison rats in medieval Spain and in 16th century England.[15]

Occurrence

Realgar most commonly occurs as a low-temperature hydrothermal vein mineral associated with other arsenic and antimony minerals. It also occurs as volcanic sublimations and in hot spring deposits. It occurs in association with orpiment, arsenolite, calcite and barite.[2]

It is found with lead, silver and gold ores in Hungary, Bohemia and Saxony. In the US it occurs notably in Mercur, Utah; Manhattan, Nevada; and in the geyser deposits of Yellowstone National Park.[5]

After a long period of exposure to light, realgar changes form to a yellow powder known as pararealgar (β-As4S4). It was once thought that this powder was the yellow sulfide orpiment, but is a distinct chemical compound.[16]

Gallery

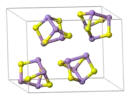

The unit cell of realgar, showing clearly the As4S4 molecules it contains

The unit cell of realgar, showing clearly the As4S4 molecules it contains Cluster of realgar crystals from Getchell Mine, Adam Peak, Potosi District, Humboldt County, Nevada, United States

Cluster of realgar crystals from Getchell Mine, Adam Peak, Potosi District, Humboldt County, Nevada, United States Cherry-red realgar crystals atop a matrix, and a sharp acicular spray of the rare species picropharmacolite (white needles) below

Cherry-red realgar crystals atop a matrix, and a sharp acicular spray of the rare species picropharmacolite (white needles) below Crystals of realgar, quartz, chalcopyrite and galena, from Quiruvilca Mine, La Libertad, Peru

Crystals of realgar, quartz, chalcopyrite and galena, from Quiruvilca Mine, La Libertad, Peru

See also

- Classification of minerals

- List of inorganic pigments

- List of minerals

- Realgar wine or Xionghuang wine is a Chinese alcoholic drink that is made from Chinese liquor dosed with powdered realgar.[17]

References

- ↑ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- 1 2 3 "Realgar" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. RRUFF Project.

- ↑ Realgar, Mindat.org

- ↑ Realgar, WebMineral.com

- 1 2 Klein, Cornelis; Hurlbut, Cornelius S. (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (20th ed.). Wiley. p. 282. ISBN 0-471-80580-7.

- ↑ Hejny, Clivia; Sagl, Raffaela; Többens, Daniel M.; Miletich, Ronald; Wildner, Manfred; Nasdala, Lutz; Ullrich, Angela; Balic-Zunic, Tonci (May 2012). "Crystal-structure properties and the molecular nature of hydrostatically compressed realgar". Physics and Chemistry of Minerals. 39 (5): 399–412. Bibcode:2012PCM....39..399H. doi:10.1007/s00269-012-0495-y. S2CID 96885484.

- ↑ Philip Babcock Grove, ed. (1993). Webster's Third New International Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, inc. ISBN 3-8290-5292-8.

- ↑ "Bonazziite".

- ↑ "List of Minerals". 21 March 2011.

- ↑ "Arsenic" (PDF). Mineral commodity summaries. United States Geological Survey. January 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ↑ Realgar (PDF). N.J. Department of Environmental Protection (Report). Hazardous Substance Factsheet. State of New Jersey. April 2008.

- 1 2 3 Arnould, Dominique (1993). "Boire le sang de taureau: La mort de Thémistocle" [Drinking bull's blood: The death of Themistocles]. Revue de philologie, de littérature et d'histoire anciennes (in French). LXVII (2): 229–235.

- ↑ Jie Liu; Yuanfu Lu; Qin Wu; Robert A. Goyer; Michael P. Waalkes (August 2008). "Mineral arsenicals in traditional medicines: Orpiment, realgar, and arsenolite" (PDF). Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 326 (2): 363–368. doi:10.1124/jpet.108.139543. PMC 2693900. PMID 18463319. Retrieved 2021-06-05. — On the toxicity of these medications

- ↑ "Realgar". Boston, MA: Museum of Fine Arts.

- ↑ "[no title cited]". Clarendon Press at Oxford. 1914 – via archive.org.

"[no title cited]" (in French). Beyrouth Impr. Catholique. 1890 – via archive.org. - ↑ Douglass, D. L.; Shing, Chichang; Wang, Ge (1992). "The light-induced alteration of realgar to pararealgar" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 77: 1266–1274. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ "Dragon Boat Festival activities expanded". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

Further reading

- The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals. 11th Edition. Ed. Susan Budavari. Merck & Co., Inc., N.J., U.S.A. 1989.

- William Mesny. Mesny’s Chinese Miscellany. A Text Book of Notes on China and the Chinese. Shanghai. Vol. III, (1899), p. 251; Vol. IV, (1905), pp. 425–426.

- American Mineralogist Vol 80, pp 400–403, 1995

- American Mineralogist Vol 20, pp 1266–1274, 1992