| ||

|---|---|---|

Ministerial career President of the Liberal Democratic Party

Elections

|

||

Beginning in November 2023,[1] a scandal involving the misuse of campaign funds by members of the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan's conservative Seiwa Seisaku Kenkyūkai and Shisuikai factions became public after it was revealed the faction had failed to report over ¥600 million in campaign funds and stored them in illegal slush funds. The scandal has led to discussions regarding the future of the LDP and its political dominance in Japan.

Background

The Liberal Democratic Party has been the dominant party in Japanese politics since its formation in 1955. The dominance of the LDP, referred to popularly as the 1955 System, has only been interrupted twice: between 1993 and 1994, as a result of corruption scandals and the end of the Japanese asset price bubble,[2] and from 2009 to 2012 as a result of continuing economic crisis during the Lost Decades.[3] The LDP later recovered both times; in 1994 by forming a coalition with the Japan Socialist Party,[4] and in 2012 as a result of the Fukushima nuclear accident a year prior.[5]

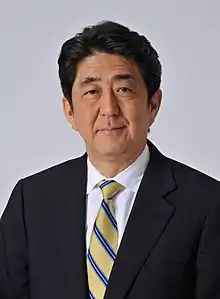

The LDP has numerous factions, but since 2012 has been dominated by the right-wing Seiwa Seisaku Kenkyūkai, also referred to as the Seiwakai or Abe faction. Formerly led by Shinzo Abe (for whom it is nicknamed), the Seiwakai continued to wield significant influence even after Abe resigned as Prime Minister in 2020.[6] Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is a member of the liberal Kōchikai faction, which competes with the Seiwakai for influence.[7] Other factions include the Shisuikai, or Nikai faction, led by Toshihiro Nikai, the Shikōkai, led by Tarō Asō, and the Heisei Kenkyūkai, led by Toshimitsu Motegi, among others.[8]

Following the assassination of Shinzo Abe in 2022, the LDP's popularity was significantly shaken after the extent of political influence by the Unification Church new religious movement was revealed.[9] Kishida reshuffled his cabinet on 10 August 2022 in an attempt to purge UC-associated ministers from the government and regain popular support,[9] but public scrutiny continued over remaining cabinet officials with connections to the church, and support for Kishida's government dropped by a further 16% according to polls conducted by the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper.[10]

Amidst continuing unpopularity, Kishida again reshuffled his cabinet on 13 September 2023, promising change. The new cabinet was primarily noted by The Japan Times as having a relatively-high number of women in official positions, as well as including members of rival factions in high-ranking positions ahead of a leadership election within the LDP in 2024. The Japan Times assessed that the placement of Heisei Kenkyūkai leader Motegi as Secretary-General of the Liberal Democratic Party was a measure to reduce his ability to criticise Kishida, while Shikōkai member Taro Kono was appointed as Minister for Digital Transformation despite controversy regarding his handling of a Individual Number Card data breach. Important Seiwakai members Kōichi Hagiuda and Hirokazu Matsuno retained their cabinet positions, as did Shikōkai leader Asō.[11]

Scandal

On 8 December 2023 Kishida, as well as other members of the LDP, were questioned by opposition lawmakers during a meeting of the National Diet. According to initial public allegations, dozens of members of the Diet from the Seiwakai were suspected of collecting at least ¥100 million from fundraising and storing the money in slush funds, in violating of Japanese campaign finance and election law. Amidst questioning, Kishida stated that the scandal was being publicly investigated and ordered the LDP to stop fundraising. Hirokazu Matsuno, Chief Cabinet Secretary, was the first individual to be named in the scandal. According to the allegations, he diverted over ¥10 million from fundraising events to a slush fund over a timeline of five years. Matsuno refused to speak about the scandal, noting that it was under investigation by police, and stated that the Seiwakai was investigating its accounts.[12]

On 13 December 2023,[13] amidst the growing size of the scandal, Kishida announced the removal of four ministers from his cabinet: Matsuno, Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry Yasutoshi Nishimura, Minister for Internal Affairs and Communications Junji Suzuki, and Minister of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries Ichiro Miyashita. Deputy Minister of Defence Hiroyuki Miyazawa was also removed from office.[5] All of the removed officials were members of the Seiwakai, while Matsuno's replacement, Yoshimasa Hayashi, was a member of the Kōchikai.[13]

The same day as the removal of the Seiwakai ministers, the opposition Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan filed a motion of no confidence in Kishida's cabinet, which was defeated due to LDP dominance in the Diet's chambers. CDPJ and Japanese Communist Party parliamentarians criticised the government's response to the scandal, with CDPJ leader Kenta Izumi saying that the LDP lacked "self-cleansing ability" and JCP leader Kazuo Shii calling it a "bottomless, serious problem." Miyazawa said following his removal that the Seiwakai faction leadership had told him "it's okay to not enter" kickbacks received between 2020 and 2022, and therefore assumed the practice was legal.[13]

The scandal continued to grow late into the month, as the National Police Agency raided the Seiwakai and Shisuikai headquarters. The NPA said that five of six LDP factions, including Kishida's Kōchikai, were under investigation for improper usage of slush funds. Kishida, who was unrelated to the scandal, left the Kōchikai as information regarding their involvement in the scandal became public. He further promised legal reforms and anti-corruption measures, promising to act as a "ball of fire."[5]

On 7 January 2024 the first arrests in the scandal were made, with former deputy Minister of Education Yoshitaki Ikeda and his aide Kazuhiro Kakinuma being charged with covering up ¥48 million received by the Seiwakai between 2018 and 2022. The NPA cited the possibility of destruction of evidence as a reason for their arrest. After information about the arrests became public, Ikeda was expelled from the LDP.[14]

Aftermath

Kishida's approval ratings have continued to fall as a result of the scandal, decreasing to 23% as of 13 December 2023, the lowest such rating any Prime Minister has had since the LDP's 2012 return to power.[13] By 22 December Kishida's approval ratings had further declined to 17%.[5] Per a 18 December 2023 Mainichi Shimbun poll, 79% of individuals polled disapprove of Kishida's performance as Prime Minister, the highest disapproval since the end of World War II. Support for the LDP, according to the poll, remained the highest of any party, with 17% above the CDPJ's 14%.[15]

Referred to by American journalist Anthony Kuhn as "Japan's worst political corruption scandal in decades," the scandal has threatened the LDP's authority and led to public speculation that the party could lose power following the next Japanese general election. Hitoshi Tanaka, a Japanese diplomat, has speculated that it could result in a change of government in Japan, potentially affecting Japan–United States relations.[1] This notion has disputed by University of Shizuoka professor Seijiro Takeshita, who has noted that the opposition to the LDP is fragmented and that the 2009–2012 Democratic Party of Japan government has continued to influence the unpopularity of the opposition. According to Takeshita, the scandal is likely to further increase political apathy and cynicism among the general population.[5] Political journalist Hiroshi Izumi has claimed without evidence that the scandal is part of a broader attempt by Kishida and the Japanese judiciary to get revenge on the Seiwakai following a series of corruption scandals under Abe's premiership that went uninvestigated.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 Kuhn, Anthony (22 December 2023). "Party bosses fall in Japan's worst political corruption scandal in decades". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 5 January 2024. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ↑ "Japanese politics and the July 1993 election". ResearchGate. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ↑ "'Major win' for Japan opposition". BBC News. 30 August 2009. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ↑ Ito, Tim. "Major Political Parties in Japan". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mao, Frances (22 December 2023). "Japan: Corruption scandal threatens PM Kishida's government". BBC News. Archived from the original on 29 December 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ↑ "LDP's biggest faction appoints leader to succeed Abe". The Japan Times. 17 August 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ↑ Taro, Kotegawa (31 October 2021). "LDP voices test Kishida's 'ability to listen' to the public in election". Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ↑ Bosack, Michael (4 January 2022). "The Evolution of LDP Factions". Tokyo Review. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- 1 2 Yamaguchi, Mari (10 August 2022). "Japan PM purges Cabinet after support falls over church ties". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 26 August 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ↑ Ito, Nanae (22 August 2022). "Support for Kishida Cabinet dives to 36% after reshuffle: Mainichi poll". Mainichi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ↑ Kanako, Takahara; Ninivaggi, Gabriele (13 September 2023). "Kishida replaces top diplomat and boosts women in Cabinet reshuffle". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 15 October 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, Mari (8 December 2023). "Japan's leader grilled in parliament over widening fundraising scandal, link to Unification Church". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- 1 2 3 4 Yamaguchi, Mari (13 December 2023). "Kishida says he regrets a ruling party funds scandal and will work on partial changes to his Cabinet". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 10 January 2024. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, Mari (7 January 2024). "Japanese prosecutors make their first arrest in the fundraising scandal sweeping the ruling party". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 10 January 2024. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ↑ Odanaka, Hiroshi (18 December 2023). "Disapproval rate for Japanese Cabinet highest since 1947: Mainichi poll". Mainichi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 8 January 2024. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)