| |

|---|---|

| |

| Tournament details | |

| Host countries | Canada Mexico United States |

| Dates | June TBD – July 19[1] |

| Teams | 48 (from 6 confederations) |

| Venue(s) | 16 (in 16 host cities) |

The 2026 FIFA World Cup, marketed as FIFA World Cup 26,[2] will be the 23rd FIFA World Cup, the quadrennial international men's soccer championship contested by the national teams of the member associations of FIFA. The tournament will take place from a yet to be determined date in June to July 19, 2026. It will be jointly hosted by 16 cities in three North American countries: Canada, Mexico, and the United States. The tournament will be the first hosted by three nations and the first North American World Cup since 1994.[3][4] Argentina is the defending champion.

This tournament will be the first to include 48 teams, expanded from 32.[5] The United 2026 bid beat a rival bid by Morocco during a final vote at the 68th FIFA Congress in Moscow. It will be the first World Cup since 2002 to be hosted by more than one nation. With its past hosting of the 1970 and 1986 tournaments, Mexico will become the first country to host or co-host the men's World Cup three times. The United States last hosted the World Cup in 1994, whereas it will be Canada's first time hosting or co-hosting the men's tournament. The event will return to its traditional northern summer schedule after the 2022 edition in Qatar was held in November and December.

Format and expansion

For the first time the FIFA World Cup will include 48 teams, an expansion by 16 compared with the previous seven tournaments. The teams will be split in 12 groups of 4 teams, with the top two of each group and the eight best third-placed teams progressing to a new round of 32, as approved by the FIFA Council on March 14, 2023.[6] This is set to be the first expansion, and change of any kind, in the competition's format since 1998.

The total number of games played will increase from 64 to 104, and the number of games played by teams reaching the final four will increase from seven to eight. The tournament is expected to last between 38 and 40 days, an increase from 32 days of the 2014 and 2018 editions.[7][8] Each team will still play three group matches.[9][10] The final matchday at club level for players named in the final squads is May 24, 2026; clubs have to release their players by May 25, with exceptions granted to players participating in continental club competition finals up until May 30. The 56 days of the combined rest, release and tournament periods remains identical to the 2010, 2014 and 2018 tournaments.[6]

The expansion to 48 teams had already been approved on January 10, 2017, when it was decided that the tournament would include 16 groups of 3 teams, and 80 matches in total, with the top two teams of each group progressing to a round of 32.[5][11] Under this format, the maximum number of games per team would have remained at seven, but each team would have played one fewer group match than before. The tournament still would have been completed within 32 days.[12] This format was chosen over three other proposals, ranging from 40 to 48 teams, from 76 to 88 matches, and from one to four minimum matches per team.[13][14][15]

Critics of this format argued that the use of three-team groups with two teams progressing significantly increased the risk of collusion between teams.[16] This prompted FIFA to suggest that penalty shoot-outs may be used to prevent draws in the group stage,[17] although even then some risk of collusion would remain, and a possibility would emerge of teams deliberately losing shootouts to eliminate a rival.[16] In view of such concerns, FIFA continued considering alternative formats.[18]

The general idea of expanding the tournament had been suggested as early as 2013 by then-UEFA president Michel Platini,[19][20] and also in 2016 by FIFA president Gianni Infantino.[21] Opponents of the proposal argued that the number of games played was already at an unacceptable level,[22] that the expansion would dilute the quality of the games,[23][24] and that the decision was driven by political rather than sporting concerns, accusing Infantino of using the promise of bringing more countries to the World Cup to win his election.[25]

Host selection

The FIFA Council went back and forth between 2013 and 2017 on limitations within hosting rotation based on the continental confederations. Originally, it was set that bids to be host would not be allowed from countries belonging to confederations that hosted the two preceding tournaments. It was temporarily changed to only prohibit countries belonging to the confederation that hosted the previous World Cup from bidding to host the following tournament,[26] before the rule was changed back to its prior state of two World Cups.

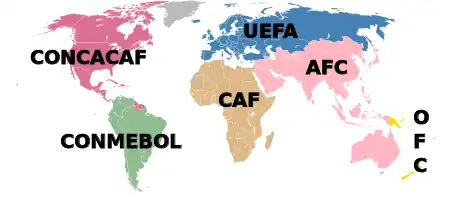

The FIFA Council made an exception to potentially grant eligibility to member associations of the confederation of the second-to-last host of the FIFA World Cup in the event that none of the received bids fulfill the strict technical and financial requirements.[27][28] In March 2017, FIFA president Gianni Infantino confirmed that "Europe (UEFA) and Asia (AFC) are excluded from the bidding following the selection of Russia and Qatar in 2018 and 2022 respectively."[29] Therefore, the 2026 World Cup could be hosted by one of the remaining four confederations: CONCACAF (North America; last hosted in 1994), CAF (Africa; last hosted in 2010), CONMEBOL (South America; last hosted in 2014), or OFC (Oceania, never hosted before), or potentially by UEFA in case no bid from those four met the requirements.

Co-hosting the FIFA World Cup—which had been banned by FIFA after the 2002 World Cup—was approved for the 2026 World Cup, though not limited to a specific number but instead evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Also for 2026, the FIFA general secretariat, after consultation with the Competitions Committee, had the power to exclude bidders who did not meet the minimum technical requirements to host the competition.[27] In March 2022, Liga MX president Mikel Arriola claimed Mexico's involvement as cohost could have been at risk if the league and the federation had not responded quickly to the Querétaro–Atlas riot between rival fans that left 26 spectators injured and resulted in 14 arrests. Arriola said FIFA was "shocked" by the incident but Infantino was satisfied with the sanctions handed down against Querétaro.[30]

Canada, Mexico, and the United States had all publicly considered bidding for the tournament separately, but the United joint bid was announced on April 10, 2017.[31][32]

| Allowed to vote | Banned from voting |

|---|---|

Voted for United bid | Canada–Mexico–United States |

Voted for Moroccan bid | Morocco |

Voted for neither | Sanctioned by FIFA |

Abstained from voting | Not a FIFA member |

Voting

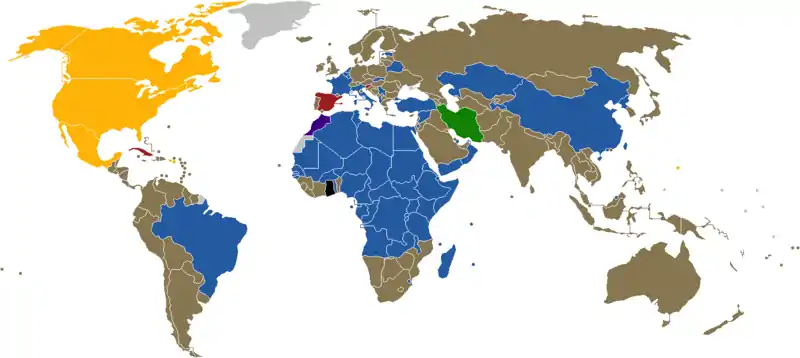

The voting took place on June 13, 2018, during the 68th FIFA Congress in Moscow, and it was opened to all 203 eligible members.[33] The United bid won with 134 valid ballots, while the Morocco bid received 65 valid ballots. Iran voted for the option "None of the bids", while Cuba, Slovenia and Spain abstained from voting.

| Nation | Vote | |

|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | ||

| Canada, Mexico, United States | 134 | |

| Morocco | 65 | |

| None of the bids | 1 | |

| Abstentions | 3 | |

| Total votes | 200 | |

| Majority required | 101 | |

Venues

|

|

|

During the bidding process, 41 cities with 43 existing, fully functional venues with regular tenants (except Montreal) and 2 venues under construction submitted to be part of the bid (3 venues in 3 cities in Mexico; 9 venues in 7 cities in Canada; 38 venues in 34 cities in the United States). A first-round elimination cut nine venues and nine cities. A second-round elimination cut an additional nine venues in six cities, while three venues in three cities (Chicago, Minneapolis, and Vancouver) dropped out due to FIFA's unwillingness to discuss financial details.[34] After Montreal dropped out in July 2021 due to lack of provincial funding and support to renovate the Olympic Stadium,[35] Vancouver rejoined the bid as a candidate city in April 2022,[36] bringing the total number to 24 venues, each in its own city or metropolitan area.

On June 16, 2022, the sixteen host cities (2 in Canada, 3 in Mexico, 11 in the United States) were announced by FIFA: Vancouver, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Guadalajara, Kansas City, Dallas, Houston, Atlanta, Monterrey, Mexico City, Toronto, Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, and Miami.[37] Eight of the sixteen chosen stadiums have permanent artificial turf surfaces that are planned to be replaced with grass under the direction of FIFA and a University of Tennessee–Michigan State University research team. Four venues (Dallas, Houston, Atlanta, and Vancouver) are indoor stadiums that use retractable roof systems, all equipped with climate control while a fifth, Los Angeles, is open-air but has a translucent roof and no climate control.[38]

Although there are soccer-specific stadiums in Canada and the United States, the largest dedicated soccer-specific stadium in the U.S., Geodis Park in Nashville, seats 30,000, which falls short of FIFA's minimum of 40,000 (Toronto's BMO Field is being expanded from 30,000 to 45,500 for this tournament).[39] Stadiums including Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, Gillette Stadium in Foxborough and Lumen Field in Seattle are used by National Football League (NFL) and Major League Soccer (MLS) teams.[40] Although primarily used for gridiron football, with the American stadiums having hosted NFL teams, and Canada's stadiums hosting the Canadian Football League (CFL), all of the Canadian and American stadiums have been used on numerous occasions for soccer and are also designed to host that sport.[41]

Mexico City is the only capital of the three host nations chosen as a venue site, with Ottawa and Washington, D.C., joining Bonn (West Germany, 1974) and Tokyo (Japan, 2002) as the only capital cities not selected to host World Cup matches. Washington was a host city candidate, but combined its bid with nearby Baltimore's due to the poor state of FedExField, which was also unsuccessful. Other cities eliminated from the final hosting list were Cincinnati, Denver, Nashville, Orlando, and Edmonton. Ottawa's candidate venue, TD Place Stadium, was eliminated early on due to insufficient capacity. None of the stadiums used in the 1994 FIFA World Cup will be used in this tournament, and the Azteca is the only stadium in this tournament that was used in the 1970 and 1986 FIFA World Cups.[42]

- A † denotes a stadium used for previous men's World Cup tournaments.

- A ‡ denotes an indoor stadium with a fixed or retractable roof with interior climate control.

(East Rutherford) |

(Arlington) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Estadio Azteca† | MetLife Stadium | AT&T Stadium‡ | Arrowhead Stadium |

| Capacity: 87,523 | Capacity: 82,500 (Bid book capacity: 87,157) |

Capacity: 80,000 (Bid book capacity: 92,967) (expandable to 105,000) |

Capacity: 76,416 (Bid book capacity: 76,640) |

|

|

|

|

(Inglewood) |

|||

| NRG Stadium‡ | Mercedes-Benz Stadium‡ | SoFi Stadium | Lincoln Financial Field |

| Capacity: 72,220 (expandable to 80,000) |

Capacity: 71,000 (Bid book capacity: 75,000) (expandable to 83,000) |

Capacity: 70,240 (expandable to 100,240) |

Capacity: 69,796 (Bid book capacity: 69,328) |

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

.jpg.webp) |

(Santa Clara) |

(Foxborough) |

(Miami Gardens) | |

| Lumen Field | Levi's Stadium | Gillette Stadium | Hard Rock Stadium |

| Capacity: 69,000 (expandable to 72,000) |

Capacity: 68,500 (Bid book capacity: 70,909) (expandable to 75,000) |

Capacity: 65,878 (Bid book capacity: 70,000) |

Capacity: 64,767 (Bid book capacity: 67,518) |

|

|

|

|

(Guadalupe) |

(Zapopan) |

||

| BC Place‡ | Estadio BBVA | Estadio Akron | BMO Field |

| Capacity: 54,500 | Capacity: 53,500 (Bid book capacity: 53,460) |

Capacity: 49,850 (Bid book capacity: 48,071) |

Capacity: 30,000 (Expanding to 45,736 for tournament) |

|

|

|

|

Teams

Qualification

The United Bid personnel anticipated that all three host countries would be awarded automatic berths.[43] On August 31, 2022, FIFA President Gianni Infantino confirmed that six CONCACAF teams will qualify for the World Cup, with Canada, Mexico, and the United States automatically qualifying as hosts.[44][45] This was confirmed by the FIFA Council on February 14, 2023.[46][47][48]

Immediately prior to the 67th FIFA Congress, the FIFA Council approved the slot allocation in a meeting in Manama, Bahrain.[49][50] This includes an intercontinental play-off tournament involving six teams to decide the last two FIFA World Cup spots.[51]

The six teams in the play-offs will comprise one team from each confederation excluding UEFA, and one additional team from the confederation of the host countries (CONCACAF). Two of the teams will be seeded based on the World Rankings, and they will play-off against the winners of two knockout games between the four unseeded teams for the two FIFA World Cup berths. The four-game tournament is to be played in one or more of the host countries, and will also be used as a test event for the FIFA World Cup.[49] The ratification of slot allocation also gives the OFC a guaranteed berth in the final tournament for the first time: the 2026 FIFA World Cup will be the first tournament in which all six confederations have at least one guaranteed berth. This will also be the first time since the 2010 edition in which all continents have a team qualified for the World Cup finals.[49]

Marketing

Branding

The official emblem and brand identity was unveiled on May 17, 2023, at the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, California; its basic form consists of a stacked "26" with an image of the FIFA World Cup Trophy in front of it (marking the first time that the trophy has been depicted in a World Cup emblem as a photo, as opposed to a stylized representation), but it is designed to be adaptable to different backdrops.[52][53] The next day, FIFA unveiled variants of the emblem for each of the host cities, which feature color variants and designs that reflect local landscapes or culture (with the Los Angeles emblem featuring a stylized sun and wave, the Monterrey emblem featuring imagery of the Cerro de la Silla mountain, and Toronto featuring the city skyline and CN Tower).[54][55]

Reaction to the logo from the initial unveiling was largely negative, with many feeling that the design was either unfinished or uncreative compared to the emblems of past FIFA World Cup tournaments. By contrast, United States national team player Jesús Ferreira described the emblem as "beautiful".[56][53][57]

Broadcasting rights

.svg.png.webp) Australia – SBS[58]

Australia – SBS[58] Austria – ORF[59]

Austria – ORF[59] Brazil – TV Globo, SporTV[60]

Brazil – TV Globo, SporTV[60] Bulgaria – NOVA[61]

Bulgaria – NOVA[61] Bosnia and Herzegovina – BHRT, MY TV[62]

Bosnia and Herzegovina – BHRT, MY TV[62].svg.png.webp) Canada – TSN, CTV, RDS[63]

Canada – TSN, CTV, RDS[63] Denmark – DR, TV2[64]

Denmark – DR, TV2[64] Finland – YLE, MTV[65]

Finland – YLE, MTV[65] Norway – NRK, TV2[66]

Norway – NRK, TV2[66] Sweden – SVT, TV4[65]

Sweden – SVT, TV4[65] United States – Fox, Telemundo[67]

United States – Fox, Telemundo[67]

On February 12, 2015, FIFA renewed the U.S. and Canadian broadcasting rights contracts for Fox, Telemundo, and CTV/TSN parent company Bell Media to cover 2026, without accepting any other bids. A report in The New York Times asserted that this extension was intended as compensation for the rescheduling of the 2022 World Cup to November–December rather than its traditional June–July scheduling, as it created considerable conflicts with major professional sports leagues that are normally in their off-season during the World Cup.[68][69][70]

References

- ↑ "Updates on the Men's and Women's International Match Calendars" (PDF). FIFA Circular Letter. No. 1840. Zürich: FIFA. April 6, 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

The final of the FIFA World Cup 2026 will take place on 19 July 2026, with the date of the opening match to be confirmed in due course.

- ↑ "FIFA World Cup 26 official brand unveiled at iconic LA landmark". 90min.com. May 18, 2023. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- ↑ "World Cup 2026: Canada, US & Mexico joint bid wins right to host tournament". BBC Sport. June 13, 2018. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ↑ Carlise, Jeff (April 10, 2017). "U.S., neighbors launch 2026 World Cup bid". ESPN. Archived from the original on April 11, 2017.

- 1 2 "Unanimous decision expands FIFA World Cup to 48 teams from 2026". FIFA. January 10, 2017. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- 1 2 "FIFA Council approves international match calendars". FIFA. March 14, 2023. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ↑ Ingle, Sean (March 14, 2023). "World Cup 2026: four-team groups and 104 game-tournament confirmed by Fifa". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ↑ Bushnell, Henry (March 14, 2023). "FIFA scraps ill-fated 2026 World Cup format, but new plan presents other pros and cons". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ↑ Ziegler, Martyn (March 14, 2023). "World Cup will be a week longer — but Fifa scraps three-team group plan". The Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ↑ Slater, Matt; Ornstein, David (March 14, 2023). "World Cup 2026 format expands again with four-team groups and 104 matches". The Athletic. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ↑ "Fifa approves Infantino's plan to expand World Cup to 48 teams from 2026". The Guardian. January 10, 2017. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ↑ "World Cup: Gianni Infantino defends tournament expansion to 48 teams". BBC Sport. January 10, 2017. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017.

- ↑ "New Fifa chief backs 48-team World Cup". HeraldLIVE. October 7, 2016. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016.

It's an idea, just as the World Cup with 40 teams is already on the table with groups of four or five teams.

- ↑ "FIFA's 5 options for a 2026 World Cup of 48, 40 or 32 teams". Yahoo! Sports. Associated Press. December 23, 2016. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017.

- ↑ "FIFA World Cup format proposals" (PDF). FIFA. December 19, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 15, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- 1 2 Guyon, Julien (April 30, 2020). "Risk of Collusion: Will Groups of 3 Ruin the FIFA World Cup?". Journal of Sports Analytics. 6 (4): 259–279. doi:10.3233/JSA-200414.

- ↑ "Penalty shootouts may be used to settle drawn World Cup matches". World Soccer. January 18, 2017. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ Ziegler, Martyn (April 1, 2022). "Format for 2026 World Cup could be revamped amid 'collusion' fears, says Fifa vice-president". The Times. London. Archived from the original on November 13, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ↑ "Michel Platini calls for 40-team World Cup starting with Russia 2018". The Guardian. October 28, 2013. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ↑ "Michel Platini's World Cup expansion plan unlikely – Fifa". BBC Sport. October 29, 2013. Archived from the original on April 21, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ↑ "Infantino suggests 40-team World Cup finals". Independent Online. South Africa: IOL. Reuters. March 30, 2016. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016.

- ↑ "World Cup: Europe's top clubs oppose FIFA's expansion plans". CNN. December 15, 2016. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Low confirms opposition to 40-team World Cup". sbs.com.au. Australian Associated Press. October 2, 2016. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Mundial de 48 equipos: durísimas críticas en Europa". Clarín (in Spanish). January 10, 2017. Archived from the original on January 12, 2017.

- ↑ "Críticas a decisión de la FIFA de jugar el Mundial 2026 con 48 selecciones". El Universo (in Spanish). Agence France-Presse. January 10, 2017. Archived from the original on January 11, 2017.

- ↑ "Current allocation of FIFA World Cup confederation slots maintained". FIFA. May 30, 2015. Archived from the original on May 30, 2015.

- 1 2 "FIFA Council discusses vision for the future of football". FIFA. October 14, 2016. Archived from the original on October 17, 2016.

- ↑ "FIFA blocks Europe from hosting 2026 World Cup, lifting Canada's chances". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Associated Press. October 14, 2016. Archived from the original on October 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Trump travel ban could prevent United States hosting World Cup". The Guardian. March 9, 2017. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ↑ Garcia, Arriana (March 9, 2022). "Mexico violence almost cost World Cup 2026 hosting duties - Liga MX president". ESPN. Archived from the original on March 17, 2022. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ↑ "USA, Mexico, Canada announce bid to host '26 WC". Sports Illustrated. April 10, 2017. Archived from the original on April 11, 2017.

- ↑ Carlise, Jeff (April 10, 2017). "U.S., Mexico and Canada officially launch bid to co-host 2026 World Cup". ESPN. Archived from the original on April 11, 2017.

- ↑ Graham, Bryan Armen (June 13, 2018). "North America to host 2026 World Cup after winning vote over Morocco – as it happened". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ↑ Carlisle, Jeff (March 16, 2018). "United States-led World Cup bid cuts list of potential host cities to 23". ESPN. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ↑ "Montreal withdraws from host city selection process for 2026 World Cup". Sportsnet. July 6, 2021. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ↑ "Update on FIFA World Cup 2026 candidate host city process". FIFA. April 14, 2022. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ↑ "FIFA unveils stellar line-up of FIFA World Cup 2026 Host Cities". FIFA. June 16, 2022. Archived from the original on June 16, 2022. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- ↑ Tannenwald, Jonathan (November 2, 2022). "FIFA goes to college to study how to grow grass indoors for the 2026 men's World Cup". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on November 7, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ Cattry, Pardeep (April 22, 2021). "Toronto FC to expand BMO Field to host 2026 World Cup matches". Mlssocer.com. Major League Soccer. Archived from the original on November 24, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ↑ "World Cup 2026 host cities confirmed: What you need to know about the 16 venues". ESPN. June 16, 2022. Archived from the original on November 7, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ Jones, J. Sam (June 16, 2022). "Your guide to 2026 World Cup stadiums and locations in the US, Mexico and Canada". MLSsoccer.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ Booth, Chuck; Gonzalez, Roger (June 17, 2022). "FIFA World Cup 2026 host cities: Los Angeles, New York/New Jersey among top venues; Washington D.C. snubbed". CBS Sports. Archived from the original on June 27, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ↑ "United 2026 bid book" (PDF). united2026.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 15, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ↑ "Presidente de la FIFA confirma cantidad de plazas de Concacaf para el Mundial de 2026". ESPN Deportes (in Spanish). August 31, 2022. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Infantino anuncia cuántos cupos tendrá la Concacaf para el Mundial de 2026". CRHoy.com (in Spanish). August 31, 2022. Archived from the original on August 31, 2022. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ↑ "FIFA Council highlights record breaking revenue in football". FIFA. February 14, 2023. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ↑ "FIFA confirms U.S., Mexico, Canada automatically in '26 World Cup". Reuters. February 14, 2023. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ↑ "USA, Canada and Mexico to qualify automatically for 2026 FIFA World Cup". The Athletic. February 14, 2023. Archived from the original on February 23, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Bureau of the Council recommends slot allocation for the 2026 FIFA World Cup". FIFA. March 30, 2017. Archived from the original on June 19, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ↑ "World Cup 2026: Fifa reveals allocation for 48-team tournament". BBC. March 30, 2017. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017.

- ↑ "FIFA Council prepares Congress, takes key decisions for the future of the FIFA World Cup". FIFA. May 9, 2017. Archived from the original on June 18, 2017.

- ↑ Cook, Glenn (May 17, 2023). "FIFA Unveils Logo For 2026 World Cup in North America". SportsLogos.Net News. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- 1 2 Cook, Glenn (May 18, 2023). "'Is That It?': Reaction to 2026 World Cup Logo Swift, Overwhelmingly Negative". SportsLogos.Net News. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ↑ Cook, Glenn (May 19, 2023). "FIFA, Host Cities Roll Out Specific Branding for 2026 World Cup". SportsLogos.Net News. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ↑ "Unprecedented Host City brands launched to bring FIFA World Cup 26™ destinations to life". www.fifa.com. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ↑ "'It's beautiful' - USMNT striker Jesus Ferreira disagrees with people who hate FIFA's World Cup 2026 logo". Goal.com. May 18, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ↑ "Fans rip FIFA World Cup 2026 logo after official reveal for men's tournament in USA, Mexico and Canada". Sporting News. May 18, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ↑ "SBS secures all rights to 2026 FIFA World Cup". October 23, 2023. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- ↑ Nambiar, Rahul (November 24, 2023). "ORF to broadcast 106 games of FIFA World Cup 2026 in Austria". Sports Mint Media. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ↑ Karter, Jonathan (November 19, 2022). "Globo renova contrato com a Fifa até 2026, mas sem exclusividade". Poder360 (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on November 19, 2022. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Nova Broadcasting Group secures broadcasting rights to UEFA EURO 2024 and UEFA EURO 2028". nova.bg (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ↑ "BHRT i BH Telecom kupuju tv prava za prenose utakmica fudbalske reprezentacije BiH". sport1.oslobodjenje.ba. January 17, 2022. Archived from the original on January 17, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ↑ Sandomir, Richard (February 12, 2015). "Fox and Telemundo to Show World Cup Through 2026 as FIFA Extends Contracts"". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ↑ Ross, Martin (December 15, 2020). "TV2 and DR continue major event rights drive with 2026 World Cup deal". Sportbusiness. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- 1 2 "TV4 to show FIFA World Cup 2026 men's contest with SVT in Sweden, with YLE in Finland". Telecompaper. Archived from the original on November 6, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ↑ "TV2, NRK add to football rights pact with 2026 World Cup deal". SportBusiness. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ↑ Parker, Ryan (February 13, 2015). "2026 World Cup TV rights awarded without bids; ESPN 'surprised'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015.

- ↑ "FIFA grants Fox, Telemundo U.S. TV rights for World Cup through 2026". Sports Illustrated. February 12, 2015. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ↑ "Why FIFA Made Deal With Fox for 2026 Cup". The New York Times. February 26, 2015. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ↑ "FIFA extending TV deals through 2026 World Cup with CTV, TSN and RDS". The Globe and Mail. February 12, 2015. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016.

External links

- FIFA World Cup 2026, FIFA.com