| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(1R,3aS,3bR,5aS,9aS,9bS,11aS)-1-Acetyl-1-hydroxy-9a,11a-dimethylhexadecahydro-7H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-7-one | |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C21H32O3 | |

| Molar mass | 332.484 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

5α-Pregnan-17α-ol-3,20-dione, also known as 17α-hydroxy-dihydroprogesterone (17‐OH-DHP) is an endogenous steroid, a metabolite of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone.

Function

5α-Pregnan-17α-ol-3,20-dione (17‐OH-DHP) is a progestogen, i.e., it binds to the progesterone receptors. However, 17‐OH-DHP is better studied as a metabolic intermediate than a progestogen per se.

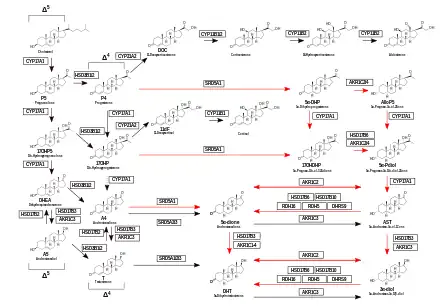

17‐OH-DHP is the first intermediate product within the androgen backdoor pathway[7] in which 17α-hydroxyprogesterone (17‐OHP) is 5α-reduced and finally converted to 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) without testosterone intermediate. The subsequent intermediate products in the pathway are 5α-pregnane-3α,17α-diol-20-one, androsterone and 5α-androstane-3α,17β-diol.[9][10] The primary feature of the androgen backdoor pathway is that 17α-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) can be 5α-reduced and finally converted to 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) via an alternative route that bypasses the conventional[11] intermediates androstenedione and testosterone.[12][13]

Biosynthesis

5α-Pregnan-17α-ol-3,20-dione is produced by 5α-reduction of 17-OHP. The reaction is catalyzed by SRD5A1[14] and possibly, SRD5A2 enzymes.[7] While the role of the SRD5A1 enzyme in this reaction is well established, it is unclear whether SRD5A2 is also involved.[13] Some authors[4][14] claim that the reduction of 17-OHP to 17OHDHP by SRD5A1 is not "sufficient" or "efficient", as supported by measurements of rat SRD5A2 activity in a 1971 study.[15] In a later study, conducted in 2017, however, it has been shown that recombinant human SRD5A1 and SRD5A2 can catalyze the reduction of 17-OHP at comparable rates to the reduction of progesterone.[16] Given both isozymes may be expressed in fetal tissues of both sexes,[17][18] the action of SRD5A2 in this reaction in humans is yet to be established.[7]

See also

References

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

- ↑ Asahina K, Suzuki K, Aida K, Hibiya T, Tamaoki B (February 1985). "Relationship between the structures and steroidogenic functions of the testes of the urohaze-goby (Glossogobius olivaceus)". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 57 (2): 281–292. doi:10.1016/0016-6480(85)90273-4. PMID 3156787.

- ↑ Gal M, Orly J (2014). "Selective inhibition of steroidogenic enzymes by ketoconazole in rat ovary cells". Clinical Medicine Insights. Reproductive Health. 8: 15–22. doi:10.4137/CMRH.S14036. PMC 4007567. PMID 24812532.

- ↑ "(5alpha)-17-Hydroxypregnane-3,20-dione - PubChem Compound Summary".

- 1 2 3 Fukami M, Homma K, Hasegawa T, Ogata T (April 2013). "Backdoor pathway for dihydrotestosterone biosynthesis: implications for normal and abnormal human sex development". Developmental Dynamics. 242 (4): 320–329. doi:10.1002/dvdy.23892. PMID 23073980. S2CID 44702659.

- ↑ Miller WL (January 2012). "The syndrome of 17,20 lyase deficiency". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 97 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-2161. PMC 3251937. PMID 22072737.

- ↑ Hastings C, Hansson V (August 1981). "Kinetic properties of the soluble 3 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from rat testis and epididymis". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. 14 (8): 705–711. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(81)90005-4. PMID 6946263.

- 1 2 3 4 Masiutin M, Yadav M (2023). "Alternative androgen pathways". WikiJournal of Medicine. 10: X. doi:10.15347/WJM/2023.003. S2CID 257943362.

- ↑ O'Shaughnessy PJ, Antignac JP, Le Bizec B, Morvan ML, Svechnikov K, Söder O, et al. (February 2019). Rawlins E (ed.). "Alternative (backdoor) androgen production and masculinization in the human fetus". PLOS Biology. 17 (2): e3000002. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000002. PMC 6375548. PMID 30763313.

- 1 2 Miller WL, Auchus RJ (April 2019). "The "backdoor pathway" of androgen synthesis in human male sexual development". PLOS Biology. 17 (4): e3000198. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000198. PMC 6464227. PMID 30943210.

- ↑ Wilson JD, Auchus RJ, Leihy MW, Guryev OL, Estabrook RW, Osborn SM, et al. (February 2003). "5alpha-androstane-3alpha,17beta-diol is formed in tammar wallaby pouch young testes by a pathway involving 5alpha-pregnane-3alpha,17alpha-diol-20-one as a key intermediate". Endocrinology. 144 (2): 575–580. doi:10.1210/en.2002-220721. PMID 12538619.

- ↑ Kinter KJ, Anekar AA (2021). Biochemistry, Dihydrotestosterone. StatPearls. PMID 32491566.

- ↑ Auchus RJ (November 2004). "The backdoor pathway to dihydrotestosterone". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 15 (9): 432–438. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2004.09.004. PMID 15519890. S2CID 10631647.

- 1 2 Kamrath C, Hochberg Z, Hartmann MF, Remer T, Wudy SA (March 2012). "Increased activation of the alternative "backdoor" pathway in patients with 21-hydroxylase deficiency: evidence from urinary steroid hormone analysis". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 97 (3): E367–E375. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-1997. PMID 22170725. S2CID 3162065.

- 1 2 Reisch N, Taylor AE, Nogueira EF, Asby DJ, Dhir V, Berry A, et al. (October 2019). "Alternative pathway androgen biosynthesis and human fetal female virilization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (44): 22294–22299. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11622294R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1906623116. PMC 6825302. PMID 31611378.

- ↑ Frederiksen DW, Wilson JD (April 1971). "Partial characterization of the nuclear reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate: delta 4-3-ketosteroid 5 alpha-oxidoreductase of rat prostate". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 246 (8): 2584–2593. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)62328-2. PMID 4396507.

- ↑ Barnard L, Gent R, van Rooyen D, Swart AC (November 2017). "Adrenal C11-oxy C21 steroids contribute to the C11-oxy C19 steroid pool via the backdoor pathway in the biosynthesis and metabolism of 21-deoxycortisol and 21-deoxycortisone". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 174: 86–95. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.07.034. PMID 28774496. S2CID 24071400.

- ↑ Ellsworth K, Harris G (October 1995). "Expression of the type 1 and 2 steroid 5 alpha-reductases in human fetal tissues". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 215 (2): 774–780. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1995.2530. PMID 7488021.

- ↑ Lunacek A, Schwentner C, Oswald J, Fritsch H, Sergi C, Thomas LN, et al. (August 2007). "Fetal distribution of 5alpha-reductase 1 and 5alpha-reductase 2, and their input on human prostate development". The Journal of Urology. 178 (2): 716–721. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.089. PMID 17574609.