In differential geometry, an affine connection[lower-alpha 1] is a geometric object on a smooth manifold which connects nearby tangent spaces, so it permits tangent vector fields to be differentiated as if they were functions on the manifold with values in a fixed vector space. Connections are among the simplest methods of defining differentiation of the sections of vector bundles.[3]

The notion of an affine connection has its roots in 19th-century geometry and tensor calculus, but was not fully developed until the early 1920s, by Élie Cartan (as part of his general theory of connections) and Hermann Weyl (who used the notion as a part of his foundations for general relativity). The terminology is due to Cartan[lower-alpha 2] and has its origins in the identification of tangent spaces in Euclidean space Rn by translation: the idea is that a choice of affine connection makes a manifold look infinitesimally like Euclidean space not just smoothly, but as an affine space.

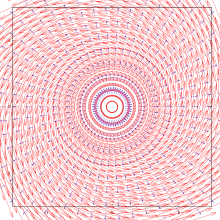

On any manifold of positive dimension there are infinitely many affine connections. If the manifold is further endowed with a metric tensor then there is a natural choice of affine connection, called the Levi-Civita connection. The choice of an affine connection is equivalent to prescribing a way of differentiating vector fields which satisfies several reasonable properties (linearity and the Leibniz rule). This yields a possible definition of an affine connection as a covariant derivative or (linear) connection on the tangent bundle. A choice of affine connection is also equivalent to a notion of parallel transport, which is a method for transporting tangent vectors along curves. This also defines a parallel transport on the frame bundle. Infinitesimal parallel transport in the frame bundle yields another description of an affine connection, either as a Cartan connection for the affine group or as a principal connection on the frame bundle.

The main invariants of an affine connection are its torsion and its curvature. The torsion measures how closely the Lie bracket of vector fields can be recovered from the affine connection. Affine connections may also be used to define (affine) geodesics on a manifold, generalizing the straight lines of Euclidean space, although the geometry of those straight lines can be very different from usual Euclidean geometry; the main differences are encapsulated in the curvature of the connection.

Motivation and history

A smooth manifold is a mathematical object which looks locally like a smooth deformation of Euclidean space Rn: for example a smooth curve or surface looks locally like a smooth deformation of a line or a plane. Smooth functions and vector fields can be defined on manifolds, just as they can on Euclidean space, and scalar functions on manifolds can be differentiated in a natural way. However, differentiation of vector fields is less straightforward: this is a simple matter in Euclidean space, because the tangent space of based vectors at a point p can be identified naturally (by translation) with the tangent space at a nearby point q. On a general manifold, there is no such natural identification between nearby tangent spaces, and so tangent vectors at nearby points cannot be compared in a well-defined way. The notion of an affine connection was introduced to remedy this problem by connecting nearby tangent spaces. The origins of this idea can be traced back to two main sources: surface theory and tensor calculus.

Motivation from surface theory

Consider a smooth surface S in a 3-dimensional Euclidean space. Near any point, S can be approximated by its tangent plane at that point, which is an affine subspace of Euclidean space. Differential geometers in the 19th century were interested in the notion of development in which one surface was rolled along another, without slipping or twisting. In particular, the tangent plane to a point of S can be rolled on S: this should be easy to imagine when S is a surface like the 2-sphere, which is the smooth boundary of a convex region. As the tangent plane is rolled on S, the point of contact traces out a curve on S. Conversely, given a curve on S, the tangent plane can be rolled along that curve. This provides a way to identify the tangent planes at different points along the curve: in particular, a tangent vector in the tangent space at one point on the curve is identified with a unique tangent vector at any other point on the curve. These identifications are always given by affine transformations from one tangent plane to another.

This notion of parallel transport of tangent vectors, by affine transformations, along a curve has a characteristic feature: the point of contact of the tangent plane with the surface always moves with the curve under parallel translation (i.e., as the tangent plane is rolled along the surface, the point of contact moves). This generic condition is characteristic of Cartan connections. In more modern approaches, the point of contact is viewed as the origin in the tangent plane (which is then a vector space), and the movement of the origin is corrected by a translation, so that parallel transport is linear, rather than affine.

In the point of view of Cartan connections, however, the affine subspaces of Euclidean space are model surfaces — they are the simplest surfaces in Euclidean 3-space, and are homogeneous under the affine group of the plane — and every smooth surface has a unique model surface tangent to it at each point. These model surfaces are Klein geometries in the sense of Felix Klein's Erlangen programme. More generally, an n-dimensional affine space is a Klein geometry for the affine group Aff(n), the stabilizer of a point being the general linear group GL(n). An affine n-manifold is then a manifold which looks infinitesimally like n-dimensional affine space.

Motivation from tensor calculus

The second motivation for affine connections comes from the notion of a covariant derivative of vector fields. Before the advent of coordinate-independent methods, it was necessary to work with vector fields by embedding their respective Euclidean vectors into an atlas. These components can be differentiated, but the derivatives do not transform in a manageable way under changes of coordinates. Correction terms were introduced by Elwin Bruno Christoffel (following ideas of Bernhard Riemann) in the 1870s so that the (corrected) derivative of one vector field along another transformed covariantly under coordinate transformations — these correction terms subsequently came to be known as Christoffel symbols.

This idea was developed into the theory of absolute differential calculus (now known as tensor calculus) by Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro and his student Tullio Levi-Civita between 1880 and the turn of the 20th century.

Tensor calculus really came to life, however, with the advent of Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity in 1915. A few years after this, Levi-Civita formalized the unique connection associated to a Riemannian metric, now known as the Levi-Civita connection. More general affine connections were then studied around 1920, by Hermann Weyl,[5] who developed a detailed mathematical foundation for general relativity, and Élie Cartan,[6] who made the link with the geometrical ideas coming from surface theory.

Approaches

The complex history has led to the development of widely varying approaches to and generalizations of the affine connection concept.

The most popular approach is probably the definition motivated by covariant derivatives. On the one hand, the ideas of Weyl were taken up by physicists in the form of gauge theory and gauge covariant derivatives. On the other hand, the notion of covariant differentiation was abstracted by Jean-Louis Koszul, who defined (linear or Koszul) connections on vector bundles. In this language, an affine connection is simply a covariant derivative or (linear) connection on the tangent bundle.

However, this approach does not explain the geometry behind affine connections nor how they acquired their name.[lower-alpha 3] The term really has its origins in the identification of tangent spaces in Euclidean space by translation: this property means that Euclidean n-space is an affine space. (Alternatively, Euclidean space is a principal homogeneous space or torsor under the group of translations, which is a subgroup of the affine group.) As mentioned in the introduction, there are several ways to make this precise: one uses the fact that an affine connection defines a notion of parallel transport of vector fields along a curve. This also defines a parallel transport on the frame bundle. Infinitesimal parallel transport in the frame bundle yields another description of an affine connection, either as a Cartan connection for the affine group Aff(n) or as a principal GL(n) connection on the frame bundle.

Formal definition as a differential operator

Let M be a smooth manifold and let Γ(TM) be the space of vector fields on M, that is, the space of smooth sections of the tangent bundle TM. Then an affine connection on M is a bilinear map

such that for all f in the set of smooth functions on M, written C∞(M, R), and all vector fields X, Y on M:

- ∇fXY = f ∇XY, that is, ∇ is C∞(M, R)-linear in the first variable;

- ∇X(fY) = (∂X f) Y + f ∇XY, where ∂X denotes the directional derivative; that is, ∇ satisfies Leibniz rule in the second variable.

Elementary properties

- It follows from property 1 above that the value of ∇XY at a point x ∈ M depends only on the value of X at x and not on the value of X on M − {x}. It also follows from property 2 above that the value of ∇XY at a point x ∈ M depends only on the value of Y on a neighbourhood of x.

- If ∇1, ∇2 are affine connections then the value at x of ∇1

XY − ∇2

XY may be written Γx(Xx, Yx) whereis bilinear and depends smoothly on x (i.e., it defines a smooth bundle homomorphism). Conversely if ∇ is an affine connection and Γ is such a smooth bilinear bundle homomorphism (called a connection form on M) then ∇ + Γ is an affine connection. - If M is an open subset of Rn, then the tangent bundle of M is the trivial bundle M × Rn. In this situation there is a canonical affine connection d on M: any vector field Y is given by a smooth function V from M to Rn; then dXY is the vector field corresponding to the smooth function dV(X) = ∂XY from M to Rn. Any other affine connection ∇ on M may therefore be written ∇ = d + Γ, where Γ is a connection form on M.

- More generally, a local trivialization of the tangent bundle is a bundle isomorphism between the restriction of TM to an open subset U of M, and U × Rn. The restriction of an affine connection ∇ to U may then be written in the form d + Γ where Γ is a connection form on U.

Parallel transport for affine connections

Comparison of tangent vectors at different points on a manifold is generally not a well-defined process. An affine connection provides one way to remedy this using the notion of parallel transport, and indeed this can be used to give a definition of an affine connection.

Let M be a manifold with an affine connection ∇. Then a vector field X is said to be parallel if ∇X = 0 in the sense that for any vector field Y, ∇YX = 0. Intuitively speaking, parallel vectors have all their derivatives equal to zero and are therefore in some sense constant. By evaluating a parallel vector field at two points x and y, an identification between a tangent vector at x and one at y is obtained. Such tangent vectors are said to be parallel transports of each other.

Nonzero parallel vector fields do not, in general, exist, because the equation ∇X = 0 is a partial differential equation which is overdetermined: the integrability condition for this equation is the vanishing of the curvature of ∇ (see below). However, if this equation is restricted to a curve from x to y it becomes an ordinary differential equation. There is then a unique solution for any initial value of X at x.

More precisely, if γ : I → M a smooth curve parametrized by an interval [a, b] and ξ ∈ TxM, where x = γ(a), then a vector field X along γ (and in particular, the value of this vector field at y = γ(b)) is called the parallel transport of ξ along γ if

- ∇γ′(t)X = 0, for all t ∈ [a, b]

- Xγ(a) = ξ.

Formally, the first condition means that X is parallel with respect to the pullback connection on the pullback bundle γ ∗ TM. However, in a local trivialization it is a first-order system of linear ordinary differential equations, which has a unique solution for any initial condition given by the second condition (for instance, by the Picard–Lindelöf theorem).

Thus parallel transport provides a way of moving tangent vectors along a curve using the affine connection to keep them "pointing in the same direction" in an intuitive sense, and this provides a linear isomorphism between the tangent spaces at the two ends of the curve. The isomorphism obtained in this way will in general depend on the choice of the curve: if it does not, then parallel transport along every curve can be used to define parallel vector fields on M, which can only happen if the curvature of ∇ is zero.

A linear isomorphism is determined by its action on an ordered basis or frame. Hence parallel transport can also be characterized as a way of transporting elements of the (tangent) frame bundle GL(M) along a curve. In other words, the affine connection provides a lift of any curve γ in M to a curve γ̃ in GL(M).

Formal definition on the frame bundle

An affine connection may also be defined as a principal GL(n) connection ω on the frame bundle FM or GL(M) of a manifold M. In more detail, ω is a smooth map from the tangent bundle T(FM) of the frame bundle to the space of n × n matrices (which is the Lie algebra gl(n) of the Lie group GL(n) of invertible n × n matrices) satisfying two properties:

- ω is equivariant with respect to the action of GL(n) on T(FM) and gl(n);

- ω(Xξ) = ξ for any ξ in gl(n), where Xξ is the vector field on FM corresponding to ξ.

Such a connection ω immediately defines a covariant derivative not only on the tangent bundle, but on vector bundles associated to any group representation of GL(n), including bundles of tensors and tensor densities. Conversely, an affine connection on the tangent bundle determines an affine connection on the frame bundle, for instance, by requiring that ω vanishes on tangent vectors to the lifts of curves to the frame bundle defined by parallel transport.

The frame bundle also comes equipped with a solder form θ : T(FM) → Rn which is horizontal in the sense that it vanishes on vertical vectors such as the point values of the vector fields Xξ: Indeed θ is defined first by projecting a tangent vector (to FM at a frame f) to M, then by taking the components of this tangent vector on M with respect to the frame f. Note that θ is also GL(n)-equivariant (where GL(n) acts on Rn by matrix multiplication).

The pair (θ, ω) defines a bundle isomorphism of T(FM) with the trivial bundle FM × aff(n), where aff(n) is the Cartesian product of Rn and gl(n) (viewed as the Lie algebra of the affine group, which is actually a semidirect product – see below).

Affine connections as Cartan connections

Affine connections can be defined within Cartan's general framework.[7] In the modern approach, this is closely related to the definition of affine connections on the frame bundle. Indeed, in one formulation, a Cartan connection is an absolute parallelism of a principal bundle satisfying suitable properties. From this point of view the aff(n)-valued one-form (θ, ω) : T(FM) → aff(n) on the frame bundle (of an affine manifold) is a Cartan connection. However, Cartan's original approach was different from this in a number of ways:

- the concept of frame bundles or principal bundles did not exist;

- a connection was viewed in terms of parallel transport between infinitesimally nearby points;[lower-alpha 4]

- this parallel transport was affine, rather than linear;

- the objects being transported were not tangent vectors in the modern sense, but elements of an affine space with a marked point, which the Cartan connection ultimately identifies with the tangent space.

Explanations and historical intuition

The points just raised are easiest to explain in reverse, starting from the motivation provided by surface theory. In this situation, although the planes being rolled over the surface are tangent planes in a naive sense, the notion of a tangent space is really an infinitesimal notion,[lower-alpha 5] whereas the planes, as affine subspaces of R3, are infinite in extent. However these affine planes all have a marked point, the point of contact with the surface, and they are tangent to the surface at this point. The confusion therefore arises because an affine space with a marked point can be identified with its tangent space at that point. However, the parallel transport defined by rolling does not fix this origin: it is affine rather than linear; the linear parallel transport can be recovered by applying a translation.

Abstracting this idea, an affine manifold should therefore be an n-manifold M with an affine space Ax, of dimension n, attached to each x ∈ M at a marked point ax ∈ Ax, together with a method for transporting elements of these affine spaces along any curve C in M. This method is required to satisfy several properties:

- for any two points x, y on C, parallel transport is an affine transformation from Ax to Ay;

- parallel transport is defined infinitesimally in the sense that it is differentiable at any point on C and depends only on the tangent vector to C at that point;

- the derivative of the parallel transport at x determines a linear isomorphism from TxM to TaxAx.

These last two points are quite hard to make precise,[9] so affine connections are more often defined infinitesimally. To motivate this, it suffices to consider how affine frames of reference transform infinitesimally with respect to parallel transport. (This is the origin of Cartan's method of moving frames.) An affine frame at a point consists of a list (p, e1,… en), where p ∈ Ax[lower-alpha 6] and the ei form a basis of Tp(Ax). The affine connection is then given symbolically by a first order differential system

defined by a collection of one-forms (θ j, ω j

i). Geometrically, an affine frame undergoes a displacement travelling along a curve γ from γ(t) to γ(t + δt) given (approximately, or infinitesimally) by

Furthermore, the affine spaces Ax are required to be tangent to M in the informal sense that the displacement of ax along γ can be identified (approximately or infinitesimally) with the tangent vector γ′(t) to γ at x = γ(t) (which is the infinitesimal displacement of x). Since

where θ is defined by θ(X) = θ1(X)e1 + … + θn(X)en, this identification is given by θ, so the requirement is that θ should be a linear isomorphism at each point.

The tangential affine space Ax is thus identified intuitively with an infinitesimal affine neighborhood of x.

The modern point of view makes all this intuition more precise using principal bundles (the essential idea is to replace a frame or a variable frame by the space of all frames and functions on this space). It also draws on the inspiration of Felix Klein's Erlangen programme,[10] in which a geometry is defined to be a homogeneous space. Affine space is a geometry in this sense, and is equipped with a flat Cartan connection. Thus a general affine manifold is viewed as curved deformation of the flat model geometry of affine space.

Affine space as the flat model geometry

Definition of an affine space

Informally, an affine space is a vector space without a fixed choice of origin. It describes the geometry of points and free vectors in space. As a consequence of the lack of origin, points in affine space cannot be added together as this requires a choice of origin with which to form the parallelogram law for vector addition. However, a vector v may be added to a point p by placing the initial point of the vector at p and then transporting p to the terminal point. The operation thus described p → p + v is the translation of p along v. In technical terms, affine n-space is a set An equipped with a free transitive action of the vector group Rn on it through this operation of translation of points: An is thus a principal homogeneous space for the vector group Rn.

The general linear group GL(n) is the group of transformations of Rn which preserve the linear structure of Rn in the sense that T(av + bw) = aT(v) + bT(w). By analogy, the affine group Aff(n) is the group of transformations of An preserving the affine structure. Thus φ ∈ Aff(n) must preserve translations in the sense that

where T is a general linear transformation. The map sending φ ∈ Aff(n) to T ∈ GL(n) is a group homomorphism. Its kernel is the group of translations Rn. The stabilizer of any point p in A can thus be identified with GL(n) using this projection: this realises the affine group as a semidirect product of GL(n) and Rn, and affine space as the homogeneous space Aff(n)/GL(n).

Affine frames and the flat affine connection

An affine frame for A consists of a point p ∈ A and a basis (e1,… en) of the vector space TpA = Rn. The general linear group GL(n) acts freely on the set FA of all affine frames by fixing p and transforming the basis (e1,… en) in the usual way, and the map π sending an affine frame (p; e1,… en) to p is the quotient map. Thus FA is a principal GL(n)-bundle over A. The action of GL(n) extends naturally to a free transitive action of the affine group Aff(n) on FA, so that FA is an Aff(n)-torsor, and the choice of a reference frame identifies FA → A with the principal bundle Aff(n) → Aff(n)/GL(n).

On FA there is a collection of n + 1 functions defined by

(as before) and

After choosing a basepoint for A, these are all functions with values in Rn, so it is possible to take their exterior derivatives to obtain differential 1-forms with values in Rn. Since the functions εi yield a basis for Rn at each point of FA, these 1-forms must be expressible as sums of the form

for some collection (θ i, ω k

j)1 ≤ i, j, k ≤ n of real-valued one-forms on Aff(n). This system of one-forms on the principal bundle FA → A defines the affine connection on A.

Taking the exterior derivative a second time, and using the fact that d2 = 0 as well as the linear independence of the εi, the following relations are obtained:

These are the Maurer–Cartan equations for the Lie group Aff(n) (identified with FA by the choice of a reference frame). Furthermore:

- the Pfaffian system θ j = 0 (for all j) is integrable, and its integral manifolds are the fibres of the principal bundle Aff(n) → A.

- the Pfaffian system ω j

i = 0 (for all i, j) is also integrable, and its integral manifolds define parallel transport in FA.

Thus the forms (ω j

i) define a flat principal connection on FA → A.

For a strict comparison with the motivation, one should actually define parallel transport in a principal Aff(n)-bundle over A. This can be done by pulling back FA by the smooth map φ : Rn × A → A defined by translation. Then the composite φ′ ∗ FA → FA → A is a principal Aff(n)-bundle over A, and the forms (θ i, ω k

j) pull back to give a flat principal Aff(n)-connection on this bundle.

General affine geometries: formal definitions

An affine space, as with essentially any smooth Klein geometry, is a manifold equipped with a flat Cartan connection. More general affine manifolds or affine geometries are obtained easily by dropping the flatness condition expressed by the Maurer-Cartan equations. There are several ways to approach the definition and two will be given. Both definitions are facilitated by the realisation that 1-forms (θ i, ω k

j) in the flat model fit together to give a 1-form with values in the Lie algebra aff(n) of the affine group Aff(n).

In these definitions, M is a smooth n-manifold and A = Aff(n)/GL(n) is an affine space of the same dimension.

Definition via absolute parallelism

Let M be a manifold, and P a principal GL(n)-bundle over M. Then an affine connection is a 1-form η on P with values in aff(n) satisfying the following properties

- η is equivariant with respect to the action of GL(n) on P and aff(n);

- η(Xξ) = ξ for all ξ in the Lie algebra gl(n) of all n × n matrices;

- η is a linear isomorphism of each tangent space of P with aff(n).

The last condition means that η is an absolute parallelism on P, i.e., it identifies the tangent bundle of P with a trivial bundle (in this case P × aff(n)). The pair (P, η) defines the structure of an affine geometry on M, making it into an affine manifold.

The affine Lie algebra aff(n) splits as a semidirect product of Rn and gl(n) and so η may be written as a pair (θ, ω) where θ takes values in Rn and ω takes values in gl(n). Conditions 1 and 2 are equivalent to ω being a principal GL(n)-connection and θ being a horizontal equivariant 1-form, which induces a bundle homomorphism from TM to the associated bundle P ×GL(n) Rn. Condition 3 is equivalent to the fact that this bundle homomorphism is an isomorphism. (However, this decomposition is a consequence of the rather special structure of the affine group.) Since P is the frame bundle of P ×GL(n) Rn, it follows that θ provides a bundle isomorphism between P and the frame bundle FM of M; this recovers the definition of an affine connection as a principal GL(n)-connection on FM.

The 1-forms arising in the flat model are just the components of θ and ω.

Definition as a principal affine connection

An affine connection on M is a principal Aff(n)-bundle Q over M, together with a principal GL(n)-subbundle P of Q and a principal Aff(n)-connection α (a 1-form on Q with values in aff(n)) which satisfies the following (generic) Cartan condition. The Rn component of pullback of α to P is a horizontal equivariant 1-form and so defines a bundle homomorphism from TM to P ×GL(n) Rn: this is required to be an isomorphism.

Relation to the motivation

Since Aff(n) acts on A, there is, associated to the principal bundle Q, a bundle A = Q ×Aff(n) A, which is a fiber bundle over M whose fiber at x in M is an affine space Ax. A section a of A (defining a marked point ax in Ax for each x ∈ M) determines a principal GL(n)-subbundle P of Q (as the bundle of stabilizers of these marked points) and vice versa. The principal connection α defines an Ehresmann connection on this bundle, hence a notion of parallel transport. The Cartan condition ensures that the distinguished section a always moves under parallel transport.

Further properties

Curvature and torsion

Curvature and torsion are the main invariants of an affine connection. As there are many equivalent ways to define the notion of an affine connection, so there are many different ways to define curvature and torsion.

From the Cartan connection point of view, the curvature is the failure of the affine connection η to satisfy the Maurer–Cartan equation

where the second term on the left hand side is the wedge product using the Lie bracket in aff(n) to contract the values. By expanding η into the pair (θ, ω) and using the structure of the Lie algebra aff(n), this left hand side can be expanded into the two formulae

where the wedge products are evaluated using matrix multiplication. The first expression is called the torsion of the connection, and the second is also called the curvature.

These expressions are differential 2-forms on the total space of a frame bundle. However, they are horizontal and equivariant, and hence define tensorial objects. These can be defined directly from the induced covariant derivative ∇ on TM as follows.

The torsion is given by the formula

If the torsion vanishes, the connection is said to be torsion-free or symmetric.

The curvature is given by the formula

Note that [X, Y] is the Lie bracket of vector fields

in Einstein notation. This is independent of coordinate system choice and

the tangent vector at point p of the ith coordinate curve. The ∂i are a natural basis for the tangent space at point p, and the X i the corresponding coordinates for the vector field X = X i ∂i.

When both curvature and torsion vanish, the connection defines a pre-Lie algebra structure on the space of global sections of the tangent bundle.

The Levi-Civita connection

If (M, g) is a Riemannian manifold then there is a unique affine connection ∇ on M with the following two properties:

- the connection is torsion-free, i.e., T∇ is zero, so that ∇XY − ∇YX = [X, Y];

- parallel transport is an isometry, i.e., the inner products (defined using g) between tangent vectors are preserved.

This connection is called the Levi-Civita connection.

The term "symmetric" is often used instead of torsion-free for the first property. The second condition means that the connection is a metric connection in the sense that the Riemannian metric g is parallel: ∇g = 0. For a torsion-free connection, the condition is equivalent to the identity X g(Y, Z) = g(∇XY, Z) + g(Y, ∇X Z), "compatibility with the metric".[11] In local coordinates the components of the form are called Christoffel symbols: because of the uniqueness of the Levi-Civita connection, there is a formula for these components in terms of the components of g.

Geodesics

Since straight lines are a concept in affine geometry, affine connections define a generalized notion of (parametrized) straight lines on any affine manifold, called affine geodesics. Abstractly, a parametric curve γ : I → M is a straight line if its tangent vector remains parallel and equipollent with itself when it is transported along γ. From the linear point of view, an affine connection M distinguishes the affine geodesics in the following way: a smooth curve γ : I → M is an affine geodesic if is parallel transported along γ, that is

where τs

t : TγsM → TγtM is the parallel transport map defining the connection.

In terms of the infinitesimal connection ∇, the derivative of this equation implies

for all t ∈ I.

Conversely, any solution of this differential equation yields a curve whose tangent vector is parallel transported along the curve. For every x ∈ M and every X ∈ TxM, there exists a unique affine geodesic γ : I → M with γ(0) = x and γ̇(0) = X and where I is the maximal open interval in R, containing 0, on which the geodesic is defined. This follows from the Picard–Lindelöf theorem, and allows for the definition of an exponential map associated to the affine connection.

In particular, when M is a (pseudo-)Riemannian manifold and ∇ is the Levi-Civita connection, then the affine geodesics are the usual geodesics of Riemannian geometry and are the locally distance minimizing curves.

The geodesics defined here are sometimes called affinely parametrized, since a given straight line in M determines a parametric curve γ through the line up to a choice of affine reparametrization γ(t) → γ(at + b), where a and b are constants. The tangent vector to an affine geodesic is parallel and equipollent along itself. An unparametrized geodesic, or one which is merely parallel along itself without necessarily being equipollent, need only satisfy

for some function k defined along γ. Unparametrized geodesics are often studied from the point of view of projective connections.

Development

An affine connection defines a notion of development of curves. Intuitively, development captures the notion that if xt is a curve in M, then the affine tangent space at x0 may be rolled along the curve. As it does so, the marked point of contact between the tangent space and the manifold traces out a curve Ct in this affine space: the development of xt.

In formal terms, let τ0

t : TxtM → Tx0M be the linear parallel transport map associated to the affine connection. Then the development Ct is the curve in Tx0M starts off at 0 and is parallel to the tangent of xt for all time t:

In particular, xt is a geodesic if and only if its development is an affinely parametrized straight line in Tx0M.[12]

Surface theory revisited

If M is a surface in R3, it is easy to see that M has a natural affine connection. From the linear connection point of view, the covariant derivative of a vector field is defined by differentiating the vector field, viewed as a map from M to R3, and then projecting the result orthogonally back onto the tangent spaces of M. It is easy to see that this affine connection is torsion-free. Furthermore, it is a metric connection with respect to the Riemannian metric on M induced by the inner product on R3, hence it is the Levi-Civita connection of this metric.

Example: the unit sphere in Euclidean space

Let ⟨ , ⟩ be the usual scalar product on R3, and let S2 be the unit sphere. The tangent space to S2 at a point x is naturally identified with the vector subspace of R3 consisting of all vectors orthogonal to x. It follows that a vector field Y on S2 can be seen as a map Y : S2 → R3 which satisfies

Denote as dY the differential (Jacobian matrix) of such a map. Then we have:

- Lemma. The formula

- defines an affine connection on S2 with vanishing torsion.

- Proof. It is straightforward to prove that ∇ satisfies the Leibniz identity and is C∞(S2) linear in the first variable. So all that needs to be proved here is that the map above does indeed define a tangent vector field. That is, we need to prove that for all x in S2

- Proof. It is straightforward to prove that ∇ satisfies the Leibniz identity and is C∞(S2) linear in the first variable. So all that needs to be proved here is that the map above does indeed define a tangent vector field. That is, we need to prove that for all x in S2

- Consider the map

- Consider the map

- The map f is constant, hence its differential vanishes. In particular

- The map f is constant, hence its differential vanishes. In particular

- Equation 1 above follows. Q.E.D.

See also

Notes

- ↑ a linear connection is also frequently called affine connection or simply connection,[1] So that there is no agreement on the precise definitions of these terms (John M. Lee simply calls it connection).[2]

- ↑ Cartan explains that he has borrowed this term (i.e. "affine connection") from the H. Weyl's book and referred to it (Space-Time-Matter), although he used it in more general context.[4]

- ↑ As a result, many mathematicians use the term linear connection (instead of affine connection) for a connection on the tangent bundle, on the grounds that parallel transport is linear and not affine. However, the same property holds for any (Koszul or linear Ehresmann) connection on a vector bundle. Originally the term affine connection is short for an affine connection in the sense of Cartan, and this implies that the connection is defined on the tangent bundle, rather than an arbitrary vector bundle. The notion of a linear Cartan connection does not really make much sense, because linear representations are not transitive.

- ↑ It is difficult to make Cartan's intuition precise without invoking smooth infinitesimal analysis, but one way is to regard his points being variable, that is maps from some unseen parameter space into the manifold, which can then be differentiated.

- ↑ Classically, the tangent space was viewed as an infinitesimal approximation, while in modern differential geometry, tangent spaces are often defined in terms of differential objects such as derivations.[8]

- ↑ This can be viewed as a choice of origin: actually it suffices to consider only the case p = ax; Cartan implicitly identifies this with x in M.

Citations

- ↑ Lee 1997, p. 51.

- ↑ Lee 2018, p. 91.

- ↑ Lee 2018, p. 88, Connections.

- ↑ Akivis & Rosenfeld 1993, p. 213.

- ↑ Weyl 1918, 5 editions to 1922.

- ↑ Cartan 1923.

- ↑ Cartan 1926.

- ↑ Kobayashi & Nomizu 1996, Volume 1, sections 1.1–1.2

- ↑ For details, see Lumiste (2001b). The following intuitive treatment is that of Cartan (1923) and Cartan (1926).

- ↑ Cf. R. Hermann (1983), Appendix 1–3 to Cartan (1951), and also Sharpe (1997).

- ↑ Kobayashi & Nomizu 1996, p. 160, Vol. I

- ↑ This treatment of development is from Kobayashi & Nomizu (1996, Volume 1, Proposition III.3.1); see section III.3 for a more geometrical treatment. See also Sharpe (1997) for a thorough discussion of development in other geometrical situations.

References

- Akivis, M. A.; Rosenfeld, Boris (1993). Élie Cartan (1869–1951). Translated by Goldberg, V. V. AMS. ISBN 978-0-8218-5355-9.

- Lee, John M. (1997). Riemannian Manifolds: An Introduction to Curvature. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 176. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-98322-6. OCLC 54850593.

- Lee, John M. (2018). Introduction to Riemannian Manifolds. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 176 (2nd ed.). Springer Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-91755-9. ISBN 978-3-319-91755-9.

Bibliography

Primary historical references

- Christoffel, Elwin Bruno (1869), "Über die Transformation der homogenen Differentialausdrücke zweiten Grades", Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik, 1869 (70): 46–70, doi:10.1515/crll.1869.70.46, S2CID 122999847

- Levi-Civita, Tullio (1917), "Nozione di parallelismo in una varietà qualunque e conseguente specificazione geometrica della curvatura Riemanniana", Rend. Circ. Mat. Palermo, 42: 173–205, doi:10.1007/bf03014898, S2CID 122088291

- Cartan, Élie (1923), "Sur les variétés à connexion affine, et la théorie de la relativité généralisée (première partie)", Annales Scientifiques de l'École Normale Supérieure, 40: 325–412, doi:10.24033/asens.751

- Cartan, Élie (1924), "Sur les variétés à connexion affine, et la théorie de la relativité généralisée (première partie) (Suite)", Annales Scientifiques de l'École Normale Supérieure, 41: 1–25, doi:10.24033/asens.753

- Cartan, Élie (1986), On Manifolds with Affine Connection and the Theory of General Relativity, Humanities Press

- Cartan's treatment of affine connections as motivated by the study of relativity theory. Includes a detailed discussion of the physics of reference frames, and how the connection reflects the physical notion of transport along a worldline.

- Cartan, Élie (1926), "Espaces à connexion affine, projective et conforme", Acta Math., 48: 1–42, doi:10.1007/BF02629755

- A more mathematically motivated account of affine connections.

- Cartan, Élie (1951), with appendices by Robert Hermann (ed.), Geometry of Riemannian Spaces (translation by James Glazebrook of Leçons sur la géométrie des espaces de Riemann, 2nd ed.), Math Sci Press, Massachusetts (published 1983), ISBN 978-0-915692-34-7.

- Affine connections from the point of view of Riemannian geometry. Robert Hermann's appendices discuss the motivation from surface theory, as well as the notion of affine connections in the modern sense of Koszul. He develops the basic properties of the differential operator ∇, and relates them to the classical affine connections in the sense of Cartan.

- Weyl, Hermann (1918), Raum, Zeit, Materie (5 editions to 1922, with notes by Jürgen Ehlers (1980), translated 4th edition Space, Time, Matter by Henry Brose, 1922 (Methuen, reprinted 1952 by Dover) ed.), Springer, Berlin, ISBN 0-486-60267-2

Secondary references

- Kobayashi, Shoshichi; Nomizu, Katsumi (1996), Foundations of Differential Geometry, Vols. 1 & 2 (New ed.), Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 0-471-15733-3.

- This is the main reference for the technical details of the article. Volume 1, chapter III gives a detailed account of affine connections from the perspective of principal bundles on a manifold, parallel transport, development, geodesics, and associated differential operators. Volume 1 chapter VI gives an account of affine transformations, torsion, and the general theory of affine geodesy. Volume 2 gives a number of applications of affine connections to homogeneous spaces and complex manifolds, as well as to other assorted topics.

- Lumiste, Ülo (2001a) [1994], "Affine connection", in Hazewinkel, Michiel (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4.

- Lumiste, Ülo (2001b) [1994], "Connections on a manifold", in Hazewinkel, Michiel (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4.

- Two articles by Lumiste, giving precise conditions on parallel transport maps in order that they define affine connections. They also treat curvature, torsion, and other standard topics from a classical (non-principal bundle) perspective.

- Sharpe, R.W. (1997), Differential Geometry: Cartan's Generalization of Klein's Erlangen Program, Springer-Verlag, New York, ISBN 0-387-94732-9.

- This fills in some of the historical details, and provides a more reader-friendly elementary account of Cartan connections in general. Appendix A elucidates the relationship between the principal connection and absolute parallelism viewpoints. Appendix B bridges the gap between the classical "rolling" model of affine connections, and the modern one based on principal bundles and differential operators.