| Anne of Bohemia | |

|---|---|

14th century manuscript of Anne's coronation | |

| Queen consort of England | |

| Tenure | 20 January 1382 – 7 June 1394 |

| Coronation | 22 January 1382 |

| Born | 11 May 1366 Prague, Kingdom of Bohemia |

| Died | 7 June 1394 (aged 28) Sheen Palace, England |

| Burial | 3 August 1394 Westminster Abbey, London |

| Spouse | |

| House | Luxembourg |

| Father | Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Mother | Elizabeth of Pomerania |

Anne of Bohemia (11 May 1366 – 7 June 1394), also known as Anne of Luxembourg, was Queen of England as the first wife of King Richard II. A member of the House of Luxembourg, she was the eldest daughter of Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia, and Elizabeth of Pomerania.[1] Her death at the age of 28 was believed to have been caused by plague.

Early life

Anne had four brothers, including the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, and one younger sister, Margaret of Bohemia, Burgravine of Nuremberg. She also had five half-siblings from her father's previous marriages, including Margaret of Bohemia, Queen of Hungary. She was brought up mainly at Prague Castle, and spent much of her early life in the care of her brother, King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia.[2] On her journey through Flanders on the way to her new life in England, she came under the protection of her uncle, Wenceslaus I, Duke of Luxembourg.[3]

Queen of England

Richard II married Anne of Bohemia (1382) as a result of the Western Schism (1378–1417) in the Papacy that had resulted in two rival popes. According to Eduard Perroy, Pope Urban VI sanctioned the marriage between Richard and Anne in an attempt to create an alliance on his behalf, particularly so that he might be stronger against the French and their preferred pope, Clement. Anne's father was the most powerful monarch in Europe at the time, ruling over about half of Europe's population and territory.[4]

The marriage was contracted against the wishes of many members of his nobility and members of parliament, and occurred primarily at the instigation of Richard's advisor Michael de la Pole. Richard had been offered Caterina Visconti, one of the daughters of Bernabò Visconti, the Lord of Milan, who would have brought a great deal of money with her as a dowry. However, instead, Anne was chosen. She brought with her no dowry, and in return for her hand in marriage, Richard gave 20,000 florins (around £4,000,000 in today's value) in payments to her brother King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia, who had written to Richard to stress their joint duty to reunite Christendom.[2] There were few diplomatic benefits – although English merchants were now allowed to trade freely within both the Bohemian lands and the lands of the Holy Roman Empire, this was not much when compared to the usual diplomatic benefits from marriages made as a result of the war with France.

Negotiations could not be completed until 1380 because Richard's negotiating team were held for ransom while returning from Prague. The marriage treaty was signed in May 1381.[2]

On her arrival in England in December 1381, having been delayed by storms,[2] Anne was severely criticised by contemporary chroniclers, probably as a result of the financial arrangements of the marriage, although it was quite typical for queens to be viewed in critical terms. The Westminster Chronicler called her "a tiny scrap of humanity",[5] and Thomas Walsingham related a disastrous omen upon her arrival; her ships smashed to pieces as soon as she had disembarked.[6] Nevertheless, Anne and King Richard II were married in Westminster Abbey on 20 January 1382. Still, the reception from Londoners was hostile at times.[2] Tournaments were held for several days after the ceremony in celebration. They then made a tour of the realm, staying at many major abbeys along the way. In 1383, Anne visited the city of Norwich, where at the Great Hospital a ceiling comprising 252 black eagles was made in her honour.[7] Anne and Richard were only 15 years old when they first met and married. Yet these "two wispy teenagers" soon fell into a loving relationship and "over the years the king proved truly devoted to his new wife".[8]

The court of Charles IV, Anne's father, based in Prague, was a centre of the International Gothic style, then at its height, and her arrival seems to have coincided with, and probably caused, new influences on English art. The Crown of Princess Blanche, now in Munich, may have been made for Anne, either in Prague or Paris.[9]

They were married for 12 years, but had no children. Anne's death from plague in 1394 at Sheen Manor was a devastating blow to Richard. He was so grief-stricken that he demolished Sheen Manor, where she had died.[10] Historians have speculated that her counsel had a moderating effect on Richard during her lifetime.[11] This is supported by his unwise conduct in the years after Anne's death that lost him his throne.[12]

Richard married his second wife, the six-year-old Isabella of Valois, on 31 October 1396.

Estimation

Although Anne was originally disliked by the chroniclers, there is some evidence that she became more popular in time. She was a very kind person and popular with the people of England; for example, she was well known for her tireless attempts to "intercede" on behalf of the people, procuring pardons for participants in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, and numerous other pardons for wrongdoers. In 1389, for example, she sought a pardon for a man who had been indicted for the murder of William de Cantilupe 14 years previously.[13]

She also made several high-profile intercessions in front of the king. Anne saved the life of John Northampton, a former mayor of London, in 1384; her humble begging convinced Richard II to merely commit the offender to lifelong imprisonment.[14] Anne's most famous act of intercession was on behalf of the citizens of London in the ceremonial reconciliation of Richard and London in 1392. The queen's role has been memorialized in Richard Maidstone's Reconciliation of Richard II with the City of London.[15]

Anne also interceded on behalf of Simon de Burley, Richard II's former tutor during his minority, in the 1388 Merciless Parliament. Despite her pleas to the Lords Appellant, Burley was executed.[16]

On the other hand, she never fulfilled many traditional duties of queens. In particular, she did not bear children, despite twelve years of marriage, and this is perhaps emphasised in her epitaph, whereby she is mentioned as having been kind to "pregnant women". The Evesham chronicler said, "this queen, although she did not bear children, was still held to have contributed to the glory and wealth of the realm, as far as she was able. Noble and common people suffered greatly at her death".[17] Nevertheless, her popular legacy as "Good Queen Anne" suggests that this lack of children was unimportant to many contemporaries.

Legacy

Anne is buried in Westminster Abbey beside her husband. In 1395, Richard sealed contracts for a monument for himself and for Anne. This was an innovation, the first time a double tomb was ordered for an English royal burial. Contracts for the base of Purbeck marble were sealed with two London masons, Henry Yevele and Stephen Lote, and for the two life size effigies with Nicholas Broker and Godfrey Prest, both coppersmiths of London. Designs, now lost, were supplied to both sets of craftsmen. The coppersmiths' contract stipulated that the effigies were to be made of gilded copper and latten and to lie under canopies. They were to be crowned, their right hands were to be joined, and they were to hold sceptres in their left hands.[18] Their joint tomb is now damaged, and the hands of the effigies are chipped off. The inscription on her tomb describes her as "beauteous in body and her face was gentle and pretty." When her tomb was opened in 1871, it was discovered that many of her bones had been stolen via a hole in the side of the casket.[19]

Anne of Bohemia is known to have made the sidesaddle more popular to ladies of the Middle Ages.[20] She also influenced the design of carts in England when she arrived in a carriage, presumably from Kocs, Hungary, to meet her future husband Richard (the name of Kocs is considered to have given rise to the English word coach). She also made the horned, Bohemian-style headdress the fashion for Englishwomen in the late 14th century.

In popular culture

Literature

- "Within the Hollow Crown" (1941), a novel by Margaret Campbell Barnes.

- "Passage to Pontefract" (1981), a novel by Jean Plaidy.

- "Frost on the Rose" (1982), a novel by Maureen Peters about Anne of Bohemia and Isabella of Valois.

- "The Last Plantagenets" (1962) by Thomas b. Costain.

Theatre

She is one of the main characters in the play Richard of Bordeaux (1932) written by Gordon Daviot. The play tells the story of Richard II of England in a romantic fashion, emphasizing the relationship between Richard and Anne of Bohemia. The play was a major hit in 1933, ran for over a year in the West End, playing a significant role in turning its director and leading man John Gielgud into a major star.

Anne also appears in Two Planks and a Passion (1983) by Anthony Minghella, in which she accompanies her husband and their close friend Robert de Vere in attending the York Corpus Christi mystery plays.

Film

- She was played by Gwen Ffrangcon Davies in a 1938 TV adaptation of the play Richard of Bordeaux. Richard II was played by Andrew Osborn. No copy has survived.

- She was played by Joyce Heron in a 1947 TV adaptation of the play Richard of Bordeaux. Richard II was played by Andrew Osborn. No copy has survived.

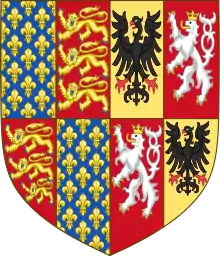

Arms

|

|

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Anne of Bohemia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ Strickland, Agnes, Lives of the Queens of England from the Norman Conquest, (Lea & Strickland, 1841), 303, 308.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hilton, Lisa (2008). Queens Consort:England's Medieval Queens. London: Phoenix. pp. 319–338. ISBN 9780753826119.

- ↑ Agnes Strickland (1841). Berengaria of Navarre. Anne of Bohemia. Lea & Blanchard. pp. 306.

- ↑ Westminster Abbey

- ↑ Westminster Chronicle 1381–1394, edited by L.C. Hector and B.F. Harvey (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982), 25.

- ↑ Thomas Walsingham, The St Albans Chronicle: The Chronica Maiora of Thomas Walsingham, Vol I: 1376–1394, ed. and trans. by John Taylor, Wendy R. Childs, and Leslie Watkiss (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003), 572–575.

- ↑ "The Great Hospital – Bishopgate, Norwich". Archived from the original on 15 November 2010. Retrieved 4 January 2011.. and Carole Rawcliffe, Medicine for the Soul: The Life, Death and Resurrection of an English Medieval Hospital St. Giles’s, Norwich, c.1249–1550 (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 1999), 118 and notes to plate 7

- ↑ Jones, Dan, The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens who made England, (Viking Press: New York, 2012), 456.

- ↑ Cherry, John, in: Jonathan Alexander & Paul Binski (eds), Age of Chivalry, Art in Plantagenet England, 1200–1400, Catalogue number 16, Royal Academy/Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1987

- ↑ "Westminster Abbey » Richard II and Anne of Bohemia". Archived from the original on 28 August 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ Costain, Thomas (1962). The Last Plantagenets. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. pp. 148, 149, 153. ISBN 978-1568493732.

- ↑ Strickland, 323–324.

- ↑ Pedersen, F. J. G. (2016b). "Murder, Mayhem and a Very Small Penis". American Historical Association. AHA. p. 6.

- ↑ Westminster Chronicle 1381–1394, edited by L.C. Hector and B.F. Harvey (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982), 93.

- ↑ Richard Maidstone (2003). David R. Carlson (ed.). Concordia (The Reconciliation of Richard II with London). Translated by A.G. Rigg. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications – via TEAMS Middle English Texts Series.

- ↑ Some chronicles record that Anne knelt before the earl of Arundel, while others indicate Thomas of Woodstock, duke of Gloucester. For Arundel, see: Chronique de la traïson et mort de Richart Deux roy D'Engleterre, ed. by Benjamin William (London : Aux dépens de la Société, 1846), 133; The Kirkstall Abbey Chronicles, ed. by John Taylor (Leeds: The Thoresby Society, 1952), 71; An English Chronicle, 1377–1461: edited from Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales MS 21068 and Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Lyell 34, ed. by William Marx (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2003), 11. For Gloucester, see: Eulogium Historiarum (continuation), ed. by Frank Scott Haydon, Vol. III (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green, 1863), 372; An English chronicle, 1377–1461, 16–7 suggests Anne knelt to both men.

- ↑ Historia Vitae et Regni Ricardi II, ed. by G.B. Stow (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1977), 134.

- ↑ "Anne of Bohemia and her contribution to Richard II's treasure".

- ↑ Richard II and Anne of Bohemia Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine at Westminster-Abbey.org. Accessed 11 March 2008.

- ↑ Strickland, Agnes (1841). Berengaria of Navarre. Anne of Bohemia. Lea & Blanchard. p. 309.

anne bohemia sidesaddle.

- ↑ Boutell, Charles (1863), A Manual of Heraldry, Historical and Popular, London: Winsor & Newton, p. 276

External links

- Images of Anne of Bohemia at the National Portrait Gallery

- Bronze Effigy of Anne of Bohemia on Westminster Tomb

- Portraits of Anne of Bohemia at the National Portrait Gallery, London