The Antiphonary tonary missal of St. Benigne (also called Antiphonarium Codex Montpellier or Tonary of Saint-Bénigne of Dijon) was written in the last years of the 10th century, when the Abbot William of Volpiano at St. Benignus of Dijon reformed the liturgy of several monasteries in Burgundy. The chant manuscript records mainly Western plainchant of the Roman-Frankish proper Mass and part of the chant sung during the matins ("Gregorian chant"), but unlike the common form of the Gradual and of the Antiphonary, William organized his manuscript according to the chant genre (antiphons with psalmody, alleluia verses, graduals, offertories, and proses for the missal part), and these sections were subdivided into eight parts according to the octoechos. This disposition followed the order of a tonary, but William of Volpiano wrote not only the incipits of the classified chant, he wrote the complete chant text with the music in central French neumes which were still written in campo aperto, and added a second alphabetic notation of his own invention for the melodic structure of the codified chant.

Historical background

This particular type of a fully notated tonary only appeared in Burgundy and Normandy. It can be regarded as a characteristic document of a certain school founded by William of Volpiano, who was reforming abbot at St. Benignus of Dijon since 989. In 1001 he followed a request by Duke Richard II and became first abbot at the Abbey of Fécamp which was a reforming centre of monasticism in Normandy.

Only this manuscript was written during the time of William by the same hand as several other manuscripts of the Library of the Medical Faculty of Montpellier (today "Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de Médecin") which all belong to St. Bénigne. It is not known, whether it was really written by William of Volpiano in person. The few things known about him can be read in a hagiographic source, the Vita domni Willelmi in fourteen chapters written by his disciple, the Burgundian monk Raoul Glaber in 1031, and revised probably by demand of the later Abbot John of Fécamp during the late 11th century.[1] William was born as son of the Alemannic Duke Robert of Volpiano at the citadel of his family on the island S. Giulio of the Lake Orta in Piedmont. The legend said that Emperor Otto had conquered this island, while William was born, so the Emperor became his patron and he was educated as a monk and made his clerical career at Cluny Abbey during the reform of Abbot Majolus who continued the reform of his predecessor Odo and supported reforms connected with papal politics under influence of the Ottonic Emperors. Concerning liturgical reforms, Emperor Otto I already emphasized the need for a reform of monasticism in Southern Italy and to abandon local liturgies in favour of the Roman rite, a kind of second Carolingian reform, and he already wished to "liberate" Arab Sicily and to organize church provinces of the island which was mainly populated by Muslims and by a Greek Christians. His plan failed after the catastrophic defeat of his son Otto II near Crotone, but the role of Cluny as a centre for liturgical reforms had increased in Ottonic times.

William's reforms were not only concerned with liturgy and the new design of local chant books, but also with the construction of new churches and buildings for abandoned abbeys, with canon law, with the organization of grammar schools and even rural communities of Normandy. It was typical for a career at Cluny Abbey to get one of the most prestigious positions as a cantor and to continue as a reforming abbot in another Abbey, which was subjected to this powerful and ambitious Abbey. As Abbot of St. Benignus William reformed several monasteries of Burgundy, Lorraine and the Île-de-France. There are some testimonies like the Libellus de revelatione, edificatione et auctoritate Fiscannensis monasterii, a chronicle of Fécamp, which reports certain resentments against Norman culture and its local liturgical customs.[2] William appeared as a Cluniac reformer, but studies of his liturgical reform especially of the Office chant for Fécamp did not confirm, that he just removed local in favour of Cluniac customs.[3] Within the reform and the history of Norman monasticism, the reform of William of Volpiano was neither the beginning nor its climax, as a reformer he had to find a balance between local needs and problems and certain interests of the Cluniac Abbot, of the Pope, and of the Norman patrons, whose founding activities cultivated a new form of policy. William contributed to this history with the foundation of an own school.

According to Véronique Gazeau he did not spend too much time in Normandy during the period about 30 years of his Norman activities, but nevertheless his school could be established, because he ordained his students as abbots.[4] He was not only Abbot at Fécamp, but also at Jumièges between 1015 and 1017. He became first Abbot of Bernay, a foundation of Countess Judith, Richard II's wife, in 1025. By order of Duke Robert he left Fécamp for John of Ravenna in 1028, before 1027 he was assisted at the Abbey at Bernay by a custos Thierry, an elder and experienced monk and prior from Saint-Bénigne of Dijon. Before he followed Suppo as prior at Mont-Saint-Michel in 1023. These administrative changes were caused by the establishment of monastic centres during certain periods, in which some Abbeys were no longer guided by an abbot, but by a prior of the community who was often called "custos", and several new foundations did not always start as an Abbey, they were subordinated to older abbeys. These monastic centres which had the control over various monasteries including former abbeys, were used to control new foundations as well as to obey liturgical and administrative reforms. This practice was continued after William's death, Fécamp and Saint-Bénigne were controlled by one abbot between 1052 and 1054: Abbot John of Ravenna. When the new founded monasteries became abbeys, the abbots were usually chosen among the monks of Fécamp.

Only few writings by William have survived in the Abbey of Fécamp, but it is not always easy to decide, if the collection of Montpellier which belonged obviously to the library of the Abbey St. Benignus of Dijon, had this Abbey as destination. Michel Huglo remarked that the last part of the manuscript H.159, the real Antiphonary with antiphons and responsories for the Matins, was continued by the 13th-century copy of the Antiphonary of the Abbey of Fécamp (Rouen, Bibliothèque municipale, Ms. 254, olim A.190).[5] So the destination of the Tonary of Saint-Bénigne is still a matter of discussion. On the other hand, customs of St. Bénigne like the liturgy for the patron can also be found in other Abbeys as Fécamp and Bernay, and the tonaries of Dijon (Montpellier, Ms. H159), of Fécamp (Rouen, Ms. 244, olim A.261), and of Jumièges (Rouen, Ms. 248, olim A.339) are so consistent that they can be regarded as documents of one school which can be ascribed to William of Volpiano.

Alphabetic notation invented by William of Volpiano

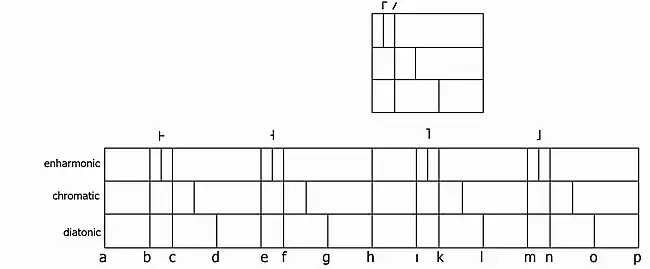

One of William's innovations as a cantor and notator was an alphabetic pitch notation. Its point of reference was the Boethian diagram, which displayed the double octave of the systema teleion in the diatonic (semitonium-tonus-tonus), the chromatic (semitonium-semitonium-trihemitonium), and the enharmonic tetrachord (diesis-diesis-ditonus). The different positions were represented by alphabetical letters, except the dieses which had special signs not unlike the tyronic letters used by Boethius:

This alphabetic pitch notation not only offers insights into microtonal shifts used by the cantors of this local school, it proves that the common projection of the piano keyboard on the medieval tone system is inadequate. Like many other letter systems used since the 8th century, also the system of William of Volpiano represented the positions of the Boethian diagram, and the enharmonic signs used for the dieses represented not a change into another genus, but microtonal attractions within the diatonic melos of a certain mode.[6]

Concerning the diesis Guido of Arezzo wrote about 1026 in his treatise Micrologus that the diesis sharpens the usual tonus between re-mi (a-b; d-e; g-h or h-i) with the proportion 9:8 by a proportion of 7:6 (a-˫; d-˧; g-Γ or h-˥).[7] Guido's explanation, how to find this interval at the monochord, made it already evident that the diesis, taken from the "enharmonic" division of the tetrachord, was used here as a microtonal shift in different melodic modes of the diatonic genus.

Composition

The Tonary of Saint-Bénigne of Dijon is organized in a very rare form of a fully notated tonary, which serves like a fully notated music manuscript for Mass (gradual) and office chant (antiphonary).[8]

The first division of the chant book is between the book's gradual (ff. 13r-155v) and an antiphonary fragment (ff. 156r-162v) which has the Matins for Palm Sunday, St. Blasius and St. Hylarius in the conventional liturgical order, but with tonal rubrics.[9] The last leaf was added from another book to use the blank versoside for additions on the last pages written by other hands, chant notated in adiastematic neumes but without alphabetic notation and even diastematic neumes with alphabetic notation (ff. 160r-163r).[10]

The gradual itself with proper Mass chant is divided into six parts: The first are antiphons (introits and communions) (ff. 13r-53r). The next three parts are chant genres which precedes lessons: alleluia verses for gospel readings (ff. 53v-69r), the benedictiones (hymnus trium puerorum) for prophetic readings (ff. 75r-76v), and the graduels for epistle readings (ff. 77r-98v). The last two parts are an offertorial (ff. 99r-151r) and a tractus collection (ff. 69r-74v; 151v-155v), dedicated to the genre which replace the alleluia verses during fasten time for all kinds of scriptural readings.[11]

The third level of division are the eight parts according to the oktoechos in the order of autentus protus, plagi proti, autentus deuterus etc. In the first part, every tonal section has all introits according to the liturgical year cycle and then all communions according to the liturgical order. The whole disposition is not new, but it is identical with tonaries from different regions of the Cluniac Monastic Association. The only difference is, that every chant is not represented by an incipit, it is fully notated in neumes and in alphabetic notation as well. Thanks to this manuscript, even cantors who do not know the chant, can memorize the melody together with its tonus.

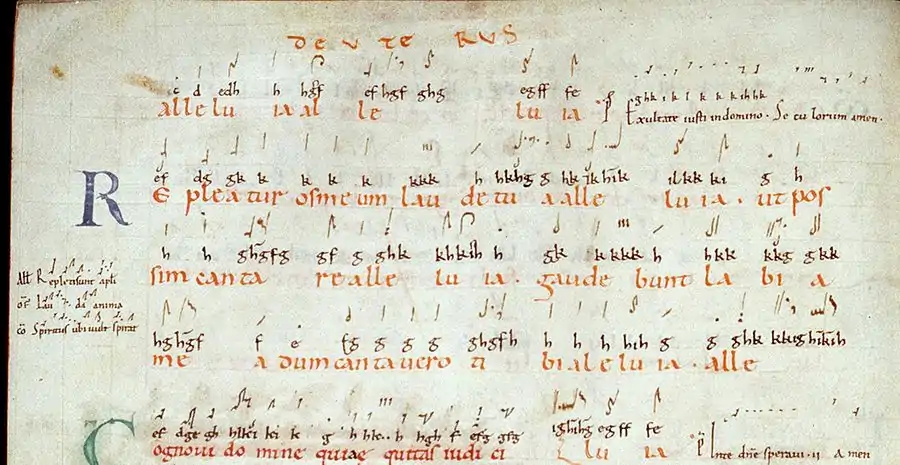

As an example might serve the Introitus "Repleatur os meum" used as a refrain for Psalm 70 during the procession into the church, at the beginning of the morning Mass on Saturday before Pentecost. The introit was written in the first part of the antiphons and is quite at the beginning of the deuterus section (written as heading on each page), hence an introit in the 3rd tone or "autentus deuterus":

The beginning with the psalm incipit and the ending of the psalmody, here called differentia no. "ii", follows the antiphon. The antiphons of the entrance (introits) have the gradual order of the Mass as a rubric at the margin (on a verso page as here: left), i.e. the serial for the day with gradual (R), alleluia (All) or tractus (TR), offertorium (OF), and communio (CO). A conventional tonary with the list of differentiae was also attached to the beginning of the manuscript.[12] It was used as an index to find the differentia no. ii or melodic ending used during the recitation of the psalm - here the incipit refers to Psalm 70 of the Vulgata. This tonary is preceded by an alleluia collection written in central French neumes in campo aperto.

The style of William of Volpiano's tonary which follows, is unique, and Michel Huglo called it one of the finest tonaries which survived in the manuscript collections today. The scribe used red ink for the chant text and different colours to decorate its initials, while the neume and the alphabetic notation was written in black ink.[13]

William of Volpiano's contribution to the evolution of musical notation

William of Volpiano's innovation of the notation system did not change the habits of central French neume notation, it just added an own alphabetic pitch notation. Often it was not clear how the letters refer to the neumes. Letter groups usually refer to the group of a ligature, but sometimes neumes were added as well to the letters to help the reading cantor for the coordination.

Among the monastic reforms of Normandy William of Volpiano was an important protagonist among the local abbots, but his alphabetic notation was only used over the following centuries in the Norman monasteries of his school, but never in the later Italo-Norman manuscripts which were rather influenced by the Aquitanian school (a few manuscripts used central French neumes, but without alphabetic notation). Within the Cluniac Monastic Association, the cantors of the following generation like Adémar de Chabannes who was taught by his uncle Roger at Saint-Martial Abbey of Limoges (Aquitaine), developed a new diastematic neume notation which allowed to indicate the ligatures, even if they were separated by the vertical disposition according to their pitch class. His innovation was imitated by Italian cantors, first in Northern Italy than in other reform centres of the 11th century like Benevento and Monte Cassino. During the 12th century one are two lines were added to help the scribe and the reader for a constant vertical orientation.

After the first generation of fully notated neume manuscripts written since the early 10th century,[14] the particular notation system represent a transition between the adiastematic and diastematic neumes. During the 11th century a lot of local traditions, different from the chant repertory of the Roman-Frankish reform, were codified the first time in diastematic neumes: Old Beneventan chant (Beneventan neumes without lines), Ravenna chant (Beneventan neumes), Old Roman chant (Roman neumes without lines), Ambrosian or Milanese chant (square neumes on a penta- or tetragramm).

See also

References

- ↑ See the edition of Véronique Gazeau and Monique Goullet (2008).

- ↑ Gazeau (2002, 44).

- ↑ See the dissertation of Olivier Diard (2000) which proves that he "corrected" chants as Raoul Glaber called it, and he also added own compositions which can only found in the two manuscripts, and he respected certain customs of the local school.

- ↑ Gazeau (2002, 39f).

- ↑ Huglo, Michel. "Tonary". New Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Nancy Phillips (2000) offers an overview.

- ↑ See: Guido D'Arezzo (1784), "Micrologus", in Gerbert, Martin (ed.), Scriptores ecclesiastici de musica sacra potissimum, vol. 2 (Hildesheim 1963 reprint ed.), St Blaise: Typis San-Blasianis, p. 11.

- ↑ It has been preserved in the Bibliothèque Inter-Universitaire, Section Médecine, at the University of Montpellier (Ms. H.159), and it was issued as a facsimile in the series illustrating the relics of ancient musical notation, Paléographie Musicale (first series, Solesmes, 1896; reprinted twice: Bern, 1972; Solesmes, 1995).

- ↑ This form was also used in a contemporary Aquitanian abridged antiphonary or breviary (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, fonds lat., Ms. 1085), the only difference is that every chant is just represented by an incipit and that the tonal classification is a Latin ordinal according to the system of Hucbald (tonus I-VIII). William of Volpiano followed also here the shape of another tonary type and used classifications like "P TE" for "Plagi tetrardi" as they were already used in the 9th-century Gradual-Sacramentary of Saint-Denis (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, fonds lat., Ms. 118).

- ↑ See folio 161 recto.

- ↑ An exact description of its content can be found in the analytic table of the facsimile edition in the serial of Paléographie musicale (VIII, 9-18).

- ↑ See the coloured reproductions of the folios 11 recto and 11 verso and the transcription in the analytic table of the PM edition (1901, VIII, 10).

- ↑ See folio 14 recto.

- ↑ One of the earliest Southern French testimonies of local melodic neume notation («notation protoaquitaine») can be found in a gradual written about 890 (Albi, Bibliothèque municipale Rochegude, Ms. 44), where only 27 pieces have musical notation and usually only in some parts. Nevertheless, the scriptor left space for the notator (see the Christmas masses on folio 5r–5v Archived March 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine), even if it had not always been used for later additions of neumes.

Bibliography

Manuscript

- William of Volpiano. "Montpellier, Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de Médecine, Ms. H159, pp.7-322". Toner-Gradual & Antiphonary of the Abbey St. Bénigne in Dijon. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

Editions

- Codex H. 159 de la Bibliothèque de l'École de médecine de Montpellier: Antiphonarium tonale missarum, XIe siècle. Paléographie musicale. Vol. 7–8. Solesmes: Abbaye Saint-Pierre de Solesmes. 1901–1905.

- Hansen, Finn Egeland, ed. (1974). H159 Montpellier: Tonary of St Bénigne of Dijon, transcribed and annotated by Finn Egeland Hansen. Studies og publikationer fra Musikvidenskabeligt Institut, Aarhus Universitet. Vol. 2. Copenhagen: Dan Fog Musikforlag. ISBN 87-87099-04-7.

Studies

- Bulst, Neithard (1973). Untersuchungen zu den Klosterreformen Wilhelms von Dijon (962-1031). Pariser historische Studien. Vol. 11. Bonn: Ludwig Röhrscheid.

- Diard, Olivier (2000). "Les offices propres dans le sanctoral normand, étude liturgique et musicale (Xe-XVe siècles)" (Document). Paris: PhD, Université de Paris IV-Sorbonne.

- Gazeau, Véronique (2002). "Guillaume de Volpiano en Normandie : état des questions". Guillaume de Volpiano : Fécamp et l' histoire normande : Actes du colloque tenu à Fécamp les 15 et 16 juin 2001. Tabularia « Études ». Vol. 2. Caen: CRAHM. pp. 35–46. doi:10.4000/tabularia.1756.

- Gazeau, Véronique; Monique Goullet (2008). Guillaume de Volpiano. Un Réformateur en son temps (962 - 1031). Caen: Publications du CRAHM. ISBN 978-2-902685-61-5.

- Gillingham, Bryan (2006). Music in the Cluniac Ecclesia: A Pilot Project. Ottawa: Institute of Mediaeval Music. ISBN 1-896926-73-8.

- Hiley, David (May 1981). The Liturgical Music of Norman Sicily: A Study centered on Manuscripts 288, 289, 19421 and Vitrina 20-4 of the Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid (Ph.D). PhD, King's College, University of London.

- Huglo, Michel (1956). "Le tonaire de Saint-Bénigne de Dijon". Annales musicologiques. 4: 7–18.

- Phillips, Nancy (2000). "Notationen und Notationslehren von Boethius bis zum 12. Jahrhundert". In Ertelt, Thomas; Zaminer, Frieder (eds.). Die Lehre vom einstimmigen liturgischen Gesang. Geschichte der Musiktheorie. Vol. 4. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. pp. 293–324. ISBN 3-534-01204-6.

External links

- "Les Manuscrits Musicaux de la Bibliothèque Interuniversitaire Médecine de Montpellier". Retrieved 2 January 2012.