| Argonauts Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female Argonauta argo with its eggs bulging out of its damaged shell | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Octopoda |

| Family: | Argonautidae |

| Genus: | Argonauta Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Argonauta argo Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Species | |

*Species status questionable. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

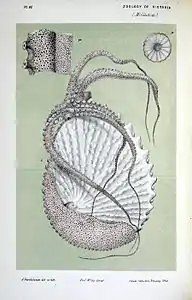

The argonauts (genus Argonauta, the only extant genus in the family Argonautidae) are a group of pelagic octopuses. They are also called paper nautili, referring to the paper-thin eggcase that females secrete. This structure lacks the gas-filled chambers present in chambered nautilus shells and is not a true cephalopod shell, but rather an evolutionary innovation unique to the genus.[1] It is used as a brood chamber, and to trap surface air to maintain buoyancy. It was once speculated that argonauts did not manufacture their eggcases but utilized shells abandoned by other organisms, in the manner of hermit crabs. Experiments by pioneering marine biologist Jeanne Villepreux-Power in the early 19th century disproved this hypothesis, as Villepreux-Power successfully reared argonaut young and observed their shells' development.[2]

Argonauts are found in tropical and subtropical waters worldwide. They live in the open ocean, i.e. they are pelagic. Like most octopuses, they have a rounded body, eight limbs (arms) and no fins. However, unlike most octopuses, argonauts live close to the surface rather than on the seabed. Argonauta species are characterised by very large eyes and small webs between the arms. The funnel–mantle locking apparatus is a major diagnostic feature of this taxon. It consists of knob-like cartilages in the mantle and corresponding depressions in the funnel. Unlike the closely allied genera Ocythoe and Tremoctopus, Argonauta species lack water pores.

Of its names, "argonaut" means "sailor of the Argo".[3] "Paper nautilus" is derived from the Greek ναυτίλος nautílos, which literally means "sailor", as paper nautili were thought to use two of their arms as sails.[4] This is not the case, as argonauts swim by expelling water through their funnels.[5] The chambered nautilus was later named after the argonaut, but belongs to a different cephalopod order, Nautilida.

Description

Sexual dimorphism and reproduction

Argonauts exhibit extreme sexual dimorphism in size and lifespan. Females grow up to 10 cm and make shells up to 30 cm, while males rarely surpass 2 cm. The males only mate once in their short lifetime, whereas the females are iteroparous, capable of having offspring many times over the course of their lives. In addition, the females have been known since ancient times, while the males were only described in the late 19th century.

The males lack the dorsal tentacles used by the females to create their eggcases. The males use a modified arm, the hectocotylus, to transfer sperm to the female. For fertilization, the arm is inserted into the female's pallial cavity and then becomes detached from the male. The hectocotylus when found in females was originally described as a parasitic worm.[6]

Mature female A. nodosa

Mature female A. nodosa Juvenile female A. hians

Juvenile female A. hians Immature male A. hians

Immature male A. hians

Eggcase

Female argonauts produce a highly laterally-compressed calcareous eggcase in which they reside. This "shell" has a double keel fringed by two rows of alternating tubercles. The sides are ribbed with the centre either flat or having winged protrusions. The eggcase curiously resembles the shells of extinct ammonites. It is secreted by the tips of the female's two greatly expanded dorsal tentacles (third left arms) before egg laying. After she deposits her eggs in the floating eggcase, the female takes shelter in it, often retaining the male's detached hectocotylus. She is usually found with her head and tentacles protruding from the opening, but she retreats deeper inside if disturbed. These ornate curved white eggcases are occasionally found floating on the sea, sometimes with the female argonaut clinging to it. It is not made of aragonite as most other shells are, but of calcite, with a three-layered structure[7] and a higher proportion of magnesium carbonate (7%) than other cephalopod shells.[8]

The eggcase contains a bubble of air that the animal captures at the surface of the water and uses for buoyancy, similarly to other shelled cephalopods, although it does not have a chambered phragmocone.[7] Once thought to contribute to occasional mass strandings on beaches, the air bubble is under sophisticated control, evident from the behaviour of animals from which air has been removed under experimental diving conditions.[9][10][11]

Most other octopuses lay eggs in caves; Neale Monks and C. Phil Palmer speculate that, before ammonites died out during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, the argonauts may have evolved to use discarded ammonite shells for their egg laying, eventually becoming able to mend the shells and perhaps make their own shells.[12] However, this is uncertain and it is unknown whether this is the result of convergent evolution.

Argonauta argo is the largest species in the genus and also produces the largest eggcase, which may reach a length of 300 mm.[13][14] The smallest species is Argonauta boettgeri, with a maximum recorded size of 67 mm.[13][15]

Female A. nodosa with its eggcase

Female A. nodosa with its eggcase The eggcase of A. argo

The eggcase of A. argo The eggcase of A. nodosa

The eggcase of A. nodosa The eggcase of A. hians

The eggcase of A. hians

Beak

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The beaks of Argonauta species are distinctive, being characterised by a very small rostrum and a fold that runs to the lower edge or near the free corner. The rostrum is "pinched in" at the sides, making it much narrower than in other octopuses, with the exception of the closely allied monotypic genera Ocythoe and Vitreledonella. The jaw angle is curved and indistinct. Beaks have a sharp shoulder, which may or may not have posterior and anterior parts at different slopes. The hood lacks a notch and is very broad, flat, and low. The hood to crest ratio (f/g) is approximately 2–2.4. The lateral wall of the beak has no notch near the wide crest. Argonaut beaks are most similar to those of Ocythoe tuberculata and Vitreledonella richardi, but differ in "leaning back" to a greater degree than the former and having a more curved jaw angle than the latter.[15]

Feeding and defense

Feeding mostly occurs during the night. Argonauts use their legs to grab prey and drag it toward the buttock. It then bites the prey to inject it with lethal poison(able to kill 200 humans) from the salivary gland. They feed on small crustaceans, molluscs, jellyfish and salps. If the prey is shelled, the argonaut uses its radula to drill into the organism, then inject the toxin.

Argonauts are capable of altering their color. They can blend in with their surroundings to avoid predators. They also produce ink, which is ejected when the animal is being attacked. This ink paralyzes the olfaction of the attacker, providing time for the argonaut to escape. The female is also able to pull back the web covering of her shell, making a silvery flash, which may deter a predator from attacking.

Argonauts are preyed upon by tunas, billfishes, and dolphins. Shells and remains of argonauts have been recorded from the stomachs of Alepisaurus ferox and Coryphaena hippurus.[15]

Male argonauts have been observed residing inside eggss, although little is known about this relationship.[16]

Classification

Fossilised eggcase of the extinct Miocene species Argonauta joanneus (lateral and keel views) |

Eggcases of six extant Argonauta species |

The genus Argonauta contains up to seven extant species. Several extinct species are also known.

Four extant species are widely considered valid:[17]

- Argonauta argo Linnaeus, 1758

- Argonauta hians Lightfoot, 1786

- Argonauta nodosus Lightfoot, 1786

- Argonauta nouryi Lorois, 1852

Several additional taxa are either treated as valid species or regarded as nomina dubia:

- Argonauta boettgeri Maltzan, 1881

- Argonauta cornutus Conrad, 1854

- Argonauta pacificus Dall, 1871

A number of extinct species have also been described:

- †Argonauta absyrtus Martill & Barker, 2006

- †Argonauta biarmata Ponzi, 1876[18]

- †Argonauta itoigawai Tomida, 1983

- †Argonauta joanneus Hilber, 1915

- †Argonauta oweri Fleming, 1945

- †Argonauta sismondai Bellardi, 1872

- †Argonauta tokunagai Yokoyama, 1913

The extinct species Obinautilus awaensis was originally assigned to Argonauta, but has since been transferred to the genus Obinautilus.[19]

Dubious or uncertain taxa

The following taxa associated with the family Argonautidae are of uncertain taxonomic status:[20]

| Binomial name and author citation | Current systematic status | Type locality | Type repository |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argonauta arctica Fabricius, 1780 | Undetermined | Unresolved; ?Tullukaurfak, Greenland | Unresolved |

| Argonauta bibula Röding, 1798 | Undetermined | Unresolved | Unresolved |

| Argonauta compressa Blainville, 1826 | Undetermined | Mer de Indes | Unresolved; [other Blainville types at MNHN] [not reported by Lu et al. (1995)] |

| Argonauta conradi Parkinson, 1856 | Species of uncertain status [fide Robson (1932:200)] | "New Nantucket, Pacific Ocean" | Unresolved |

| Argonauta cornu Gmelin, 1791 | Undetermined | Unresolved | Unresolved; LS? |

| Argonauta cymbium Linné, 1758 | Non-cephalopod; foraminiferous shell [fide Von Martens (1867:103) | ||

| Argonauta fragilis Parkinson, 1856 | Species of uncertain status [fide Robson (1932:200)] | Not designated | Unresolved |

| Argonauta geniculata Gould, 1852 | Species of uncertain status [fide Robson (1932:200)] | Near Sugarloaf Mountain, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Type not extant [fide Johnson (1964:32)] |

| Argonauta maxima Dall, 1871 | Nomen nudum | ||

| Argonauta navicula Lightfoot, 1786 | Species dubium [fide Rehder (1967:11)] | Not designated | Unresolved |

| Argonauta rotunda Perry, 1811 | Non-cephalopod; Carcinaria sp. [fide Robson (1932:201)] | ||

| Argonauta rufa Owen, 1836 | Incertae sedis [fide Robson (1932:181)] | "Indian seas" ["South Pacific ocean" fide Owen (1842:114)] | Unresolved; Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons? Holotype |

| Argonauta sulcata Lamarck, 1801 | Nomen nudum | ||

| Argonauta tuberculata f. aurita Von Martens, 1867 | Undetermined | Unresolved | ZMB |

| Argonauta tuberculata f. mutica Von Martens, 1867 | Undetermined | Coast of Brazil | ZMB Holotype |

| Argonauta tuberculata f. obtusangula Von Martens, 1867 | Undetermined | Not designated | ZMB Syntypes |

| Argonauta vitreus Gmelin, 1791 | Undetermined | Not designated | Unresolved; LS? |

| Octopus (Ocythoe) raricyathus Blainville, 1826 | Undetermined [Argonauta?] | Not designated | MNHN Holotype; specimen not extant [fide Lu et al. (1995:323)] |

| Ocythoe punctata Say, 1819 | Argonauta sp. [fide Robson (1929d:215)] | Atlantic Ocean near the North American coast (from stomach of dolphin) | Unresolved; ANSP? Holotype [not traced by Spamer and Bogan (1992)] |

| Tremoctopus hirondellei Joubin, 1895 | Argonauta or Ocythoe [fide Thomas (1977:386)] | 44°28′56″N 46°48′15″W / 44.48222°N 46.80417°W (Atlantic Ocean) | MOM Holotype [station 151] [fide Belloc (1950:3)] |

In design

The argonaut was the inspiration for a number of classical and modern art and decorative forms including use on pottery and architectural elements. Some early examples are found in Bronze Age Minoan art from Crete.[21] A variation known as the double argonaut design was also found in Minoan jewelry.[22] This design was also transposed and adapted in both gold and glass in contemporary Mycenaean contexts, as seen both at Mycenae and the Tholos at Volo.[23]

In literature and etymology

- Argonauts are featured in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, noted for their ability to use their tentacles as sails, though this is a widespread myth.

- A female argonaut is also described in Marianne Moore's poem "The Paper Nautilus".

- "Argonauta" is the name of a chapter in Anne Morrow Lindbergh's Gift from the Sea.

- Paper nautiluses were caught in The Swiss Family Robinson novel.[24]

- Argonauts gave their name to an Arabidopsis thaliana mutation and by extension to Argonaute proteins.

References

- ↑ Naef, A. (1923). "Die Cephalopoden, Systematik". Fauna Flora Golf. Napoli (35) (in German). 1: 1–863.

- ↑ Scales, Helen (2015). Spirals in Time: The Secret Life and Curious Afterlife of Seashells. Bloomsbury.

- ↑ "Word Origin and History for Argonaut". Online Etymology Dictionary. 2010. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

- ↑ "Origin of nautilus". Dictionary.com Unabridged. 2017. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

- ↑ Figuier, Louis (1869). The Ocean World: Being a Descriptive History of the Sea and Its Living Inhabitants. London: Cassell, Petter and Galpin. pp. 329.

- ↑ Delle Chiaje, S. (1825). Memorie sulla storia e notomia degli animali (in Italian). Senza Vertebre del Regno di Napoli. I.

- 1 2 Nixon, M.; Young, J. Z. (2003). The Brains and Lives of Cephalopods. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Saul, L.; Stadum, C. (2005). "Fossil Argonauts (Mollusca: Cephalopoda: Octopodida) From Late Miocene Siltstones Of The Los Angeles Basin, California". Journal of Paleontology. 79 (3): 520–531. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079<0520:FAMCOF>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 4095022. S2CID 131373540.

- ↑ Finn, J. K. & Norman, M. D. The argonaut shell: gas-mediated buoyancy control in a pelagic octopus. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, published online May 19, 2010. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0155

- ↑ "Museum Victoria 'Argonaut buoyancy' video" Archived 2012-07-13 at the Wayback Machine museumvictoria.com.au. URL accessed on 19 May 2010.

- ↑ Pidcock, R. 2010. Ancient octopus mystery resolved. BBC News, May 19, 2010.

- ↑ Monks, N.; Palmer, C. P. (2002). Ammonites. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C.

- 1 2 Pisor, D. L. (2005). Registry of World Record Size Shells (4th ed.). Snail's Pace Productions and ConchBooks. p. 12.

- ↑ (in Russian) Nesis, K. N. 1982. Abridged key to the cephalopod mollusks of the world's ocean. Light and Food Industry Publishing House, Moscow, 385+ii pp. [Translated into English by B. S. Levitov, ed. by L. A. Burgess (1987), Cephalopods of the world. T. F. H. Publications, Neptune City, NJ, 351 pp.]

- 1 2 3 Clarke, M. R. (1986). A Handbook for the Identification of Cephalopod Beaks. Oxford University Press. pp. 273 pp.

- ↑ Banas, P. T.; D. E. Smith & D. C. Biggs (1982). "An association between a pelagic octopod, Argonauta sp. Linnaeus 1758, and aggregate salps". Fish. Bull. 80: 648–650.

- ↑ Serge Gofas (2015). "Argonauta Linnaeus, 1758". World Register of Marine Species. Flanders Marine Institute. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ Ponzi, G. (1876). Cefalopodi. [p. 932 + pl. III 1a–b] In: I fossili del Monte Vaticano. Atti della Reale Accademia dei Lincei, series 2, 3(2): 925–959 + 3 pls. (in Italian)

- ↑ Martill, D.M. & M.J. Barker (2006). A paper nautilus (Octopoda, Argonauta) from the Miocene Pakhna Formation of Cyprus. Palaeontology 49 (5): 1035-1041.

- ↑ Sweeney, M. J. Taxa Associated with the Family Argonautidae Tryon, 1879. Tree of Life web project.

- ↑ Eleni M. Konstantinidi, 2001, Jewellery Revealed in the Burial Contexts of the Greek Bronze Age, Hadrian Books, 322 pages ISBN 1-84171-165-9

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan, Knossos Fieldnotes, The Modern Antiquarian (2007)

- ↑ Higgins, Reynold; Higgins, Reynold Alleyne (1980-01-01). Greek and Roman Jewellery. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03601-7.

- ↑ Johann David Wyss and Jenny H. Stickney, The Swiss Family Robinson, Ginn & Co., 1898, 364 pages.