Engineering on an astronomical scale, or astronomical engineering, i.e., engineering involving operations with whole astronomical objects (planets, stars, etc.), is a known theme in science fiction, as well as a matter of recent scientific research and exploratory engineering.[1]

On the Kardashev scale, Type II and Type III civilizations can harness energy on the required scale.[2][3] This can allow them to construct megastructures.

Examples

Exploratory engineering

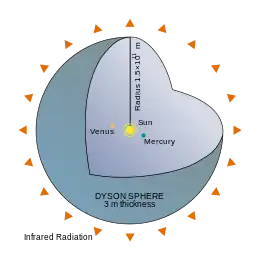

- Dyson spheres or Dyson swarm and similar constructs are hypothetical megastructures originally described by Freeman Dyson as a system of orbiting solar power satellites meant to enclose a star completely and capture most or all of its energy output.[4]

- Star lifting is a process where an advanced civilization could remove a substantial portion of a star's matter in a controlled manner for other uses.

- Matrioshka brains

- Stellar engine

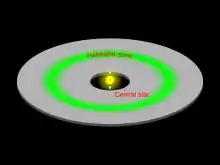

- An Alderson disk[5] (named after Dan Alderson, its originator) is a hypothetical artificial astronomical megastructure, a giant platter with a thickness of several thousand miles. The Sun rests in the hole at the center of the disk. The outer perimeter of an Alderson disk would be roughly equivalent to the orbit of Mars or Jupiter.

- A stellaser is a star-powered laser.

Science fiction

- In the Ringworld series by Larry Niven, a ring a million miles wide is built and spun (to simulate gravity) around a star roughly one astronomical unit away. The ring can be viewed as a functional version of a Dyson sphere with the interior surface area of 3 million Earth-sized planets. Because it is only a partial Dyson sphere, it can be viewed as a construction of a civilization intermediary between Type I and Type II. Both Dyson spheres and the Ringworld suffer from gravitational instability, however—a major focus of the Ringworld series is coping with this instability in the face of partial collapse of the Ringworld civilization.

- The Morlocks of Stephen Baxter's The Time Ships occupy a spherical shell around the Sun the diameter of Earth's orbit, spinning for gravity along one band. The shell's inner surface along this band is inhabited by cultures in many lower stages of development, while the K II Morlock civilization uses the entire structure for power and computation.[6]

- In the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Relics", the Enterprise discovers an abandoned Dyson sphere.[7]

- In the Halo universe, the Forerunners created many planet-sized artificial megastructures, such as the Halo ringworlds, the two Arks, and the Shield Worlds, which were micro-Dyson spheres. One of the Precursors' most well known creations were the Star Roads: immense, indestructible cables that connected planets and star systems.

- In the movie Elysium, a large-scale space habitat has been built to orbit Earth and is capable of sustaining life permanently.

- In the Corellian Trilogy (Star Wars Legends books), the Corellian system is revealed to have been constructed by an unknown ancient civilization, using Centerpoint Station to transport the planets across interstellar distances, and "planetary repulsors" to maneuver the planets into their orbits.

- In Iain M. Banks' fictional Culture universe, an Orbital is a purpose-built space habitat forming a ring typically around 3 million km (1.9 million miles) in diameter. The rotation of the ring simulates both gravity and a day-night cycle comparable to a planetary body orbiting a star.

- The Dyson shell is the variant of the Dyson sphere most often depicted in fiction. It is a uniform solid shell of matter around the star, as opposed to a swam of orbiting satellites.[8] In response to letters prompted by some papers, Dyson replied, "A solid shell or ring surrounding a star is mechanically impossible. The form of 'biosphere' which I envisaged consists of a loose collection or swarm of objects travelling on independent orbits around the star."[9]

Gallery

Dyson shell

Dyson shell Orbital with no apparent hub

Orbital with no apparent hub Alderson disk

Alderson disk A proposed plan for an orbital ring

A proposed plan for an orbital ring

See also

References

- ↑ Adams, Fred (2003). "Astronomical Engineering". Origins of Existence: How Life Emerged in the Universe. The Free Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-4391-3820-5.

- ↑ Dyson, Freeman J. (1966). Marshak, R. E. (ed.). "The Search for Extraterrestrial Technology". Perspectives in Modern Physics. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Kardashev, Nikolai. "On the Inevitability and the Possible Structures of Supercivilizations", The search for extraterrestrial life: Recent developments; Proceedings of the Symposium, Boston, MA, June 18–21, 1984 (A86-38126 17-88). Dordrecht, D. Reidel Publishing Co., 1985, p. 497–504.

- ↑ Dyson, Freeman J. (1966). "The Search for Extraterrestrial Technology". In Marshak, R. E. (ed.). Perspectives in Modern Physics: Essays in Honor of Hans Bethe. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Bibcode:1966pmp..book..641D.

- ↑ Hadhazy, Adam (5 August 2014). "Could We Build a Disk Bigger Than a Star?". Popular Mechanics.

- ↑ Alex Hormann (February 5, 2022). "BOOK REVIEW: The Time Ships, by Stephen Baxter". atboundarysedge.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Star Trek: The Next Generation Relics (TV episode 1992) - IMDb". IMDB. Retrieved 2011-11-21.

- ↑ "Dyson FAQ: What is a Dyson Sphere?". Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- ↑ Dyson, F. J.; Maddox, J.; Anderson, P.; Sloane, E. A. (1960). "Letters and Response, Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation". Science. 132 (3421): 250–253. doi:10.1126/science.132.3421.252-a. PMID 17748945.

Further reading

- Korycansky, D.G.; Laughlin, Gregory; Adams, Fred C. (2001). "Astronomical Engineering: A Strategy For Modifying Planetary Orbits". Astrophysics and Space Science. 275 (4): 349–366. arXiv:astro-ph/0102126. Bibcode:2001Ap&SS.275..349K. doi:10.1023/A:1002790227314. hdl:2027.42/41972. S2CID 5550304.

- McInnes, Colin R. (2002). "Astronomical Engineering Revisited: Planetary Orbit Modification Using Solar Radiation Pressure". Astrophysics and Space Science. 282 (4): 765–772. Bibcode:2002Ap&SS.282..765M. doi:10.1023/A:1021178603836. S2CID 118010671.

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.