.jpg.webp)

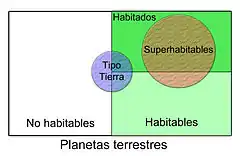

A superhabitable planet is a hypothetical type of exoplanet or exomoon that may be better suited than Earth for the emergence and evolution of life. The concept was introduced in 2014 by René Heller and John Armstrong,[2] who have criticized the language used in the search for habitable planets and proposed clarifications. According to Heller and Armstrong, knowing whether or not a planet is in its host star's habitable zone (HZ) is insufficient to determine its habitability:[3] It is not clear why Earth should offer the most suitable physicochemical parameters to living organisms, as "planets could be non-Earth-like, yet offer more suitable conditions for the emergence and evolution of life than Earth did or does." While still assuming that life requires water, they hypothesize that Earth may not represent the optimal planetary habitability conditions for maximum biodiversity; in other words, they define a superhabitable world as a terrestrial planet or moon that could support more diverse flora and fauna than there are on Earth, as it would empirically show that its environment is more hospitable to life.

Heller and Armstrong also point out that not all rocky planets in a habitable zone (HZ) may be habitable, and that tidal heating can render terrestrial or icy worlds habitable beyond the stellar HZ, such as in Europa's internal ocean.[4][n. 1] The authors propose that in order to identify a habitable—or superhabitable—planet, a characterization concept is required that is biocentric rather than geo- or anthropocentric.[2] Heller and Armstrong proposed to establish a profile for exoplanets according to stellar type, mass and location in their planetary system, among other features. According to these authors, such superhabitable worlds would likely be larger, warmer, and older than Earth, and orbiting K-type main-sequence stars.

General characteristics

Heller and Armstrong proposed that a series of basic characteristics are required to classify an exoplanet or exomoon as superhabitable;[7][2][8][9] [10] for size, it is required to be about 2 Earth masses, and 1.3 Earth radii will provide an optimal size for plate tectonics.[11] In addition, it would have a greater gravitational attraction that would increase retention of gases during the planet's formation.[10] It is therefore likely that they have a denser atmosphere that will offer greater concentration of oxygen and greenhouse gases, which in turn raise the average temperature to optimum levels for plant life to about 25 °C (77 °F).[12][13] A denser atmosphere may also influence the surface relief, making it more regular and decreasing the size of the ocean basins, which would improve diversity of marine life in shallow waters.[14]

Other factors to consider are the type of star in the system. K-type stars and low-luminosity G-type stars, collectively referred to as orange dwarfs, are less massive than the Sun, and are stable on the main sequence for a very long time (18 to 34 billion years, compared to 10 billion for the Sun, a G2V star),[15][16] giving more time for the emergence of life and evolution. In addition, orange dwarfs emit less ultraviolet radiation (which can damage DNA and thus hamper the emergence of nucleic acid based life) than stars like the Sun. Additional information on orange dwarfs, including quantitative estimates about their suitability to serve as hosts for superhabitable planets, has been given by Cuntz and Guinan.[17]

Surface, size and composition

An exoplanet with a larger volume than that of Earth, or with a more complex terrain, or with a larger surface covered with liquid water, could be more hospitable for life than Earth.[18] Since the volume of a planet tends to be directly related to its mass, the more massive it is, the greater its gravitational pull, which can result in a denser atmosphere.[19]

Some studies indicate that there is a natural radius limit, set at R🜨, below which nearly all planets are terrestrial, composed primarily of rock-iron-water mixtures.[20] It was once thought that objects with a mass below 8 M🜨 are very likely to be of similar composition as Earth;[21] above this limit, the density of the planets decreases with increasing size, the planet will become a "water world" and finally a gas giant.[22][23] In addition, for most super-Earths with masses 7 times Earth's, their high masses may cause them to lack plate tectonics.[11] Thus, it is expected that any exoplanet similar to Earth's density and with a radius under 2 R🜨 may be suitable for life.[13] However, other studies indicate that water worlds represent a transitional stage between mini-Neptunes and the terrestrial planets, especially if they belong to red dwarfs or K dwarfs.[24][25] Although water planets may be habitable, the average depth of the water and the absence of land area would not make them superhabitable as defined by Heller and Armstrong.[26] Further studies on the mass-radius relationship also indicate that the transition point between a rocky planet and a mini-Neptune usually occurs much earlier, at only about 2 M🜨;[27] exceptions to this are very close to their stars (and thus would have had their volatile atmospheres boiled away), producing very hot surface conditions not very conducive for life.[28] From a geological perspective, the optimal mass of a planet is about 2 M🜨, so it must have a radius that keeps the density of the Earth among 1.2 and 1.3R🜨.[29]

The average depth of the oceans also affects the habitability of a planet. The shallow areas of the sea, given the amount of light and heat they receive, usually are more comfortable for known aquatic species, so it is likely that exoplanets with a lower average depth are more suitable for life.[26][30] More massive exoplanets would tend to have a regular surface gravity, which can mean shallower—and more hospitable—ocean basins.[31]

Geology

Plate tectonics, in combination with the presence of large bodies of water on a planet, is able to maintain high levels of carbon dioxide (CO

2) in its atmosphere.[32][33] This process appears to be common in geologically active terrestrial planets with a significant rotation speed.[34] The more massive a planetary body, the longer time it will generate internal heat, which is a major contributing factor to plate tectonics.[11] However, excessive mass can also slow plate tectonics because of increased pressure and viscosity of the mantle, which hinders the sliding of the lithosphere.[11] Research suggests that plate tectonics peaks in activity in bodies with a mass between 1 and 5M🜨, with an optimum mass of approximately 2M🜨.[29]

If the geological activity is not strong enough to generate a sufficient amount of greenhouse gases to increase global temperatures above the freezing point of water, the planet could experience a permanent ice age, unless the process is offset by an intense internal heat source such as tidal heating or stellar irradiation.[35]

Magnetosphere

Another feature favorable to life is a planet's potential to develop a strong magnetosphere to protect its surface and atmosphere from cosmic radiation and stellar winds, especially around red dwarf stars.[36] Less massive bodies and those with a slow rotation, or those that are tidally locked, have a weak to non-existent magnetic field, which over time can result in the loss of a significant portion of its atmosphere, especially hydrogen, by hydrodynamic escape.[11]

Temperature and climate

The optimum temperature for Earth-like life in general is unknown, although it appears that on Earth organism diversity has been greater in warmer periods.[37] It is therefore possible that exoplanets with slightly higher average temperatures than that of Earth are more suitable for life.[38] The thermoregulatory effect of large oceans on exoplanets located in a habitable zone may maintain a moderate temperature range.[39][38] In this case, deserts would be more limited in area and would likely support habitat-rich coastal environments.[38]

However, studies suggest that Earth already lies near to the inner edge of the habitable zone of the Solar System,[40] and that may harm its long-term livability as the luminosities of main-sequence stars steadily increase over time, pushing the habitable zone outwards.[41][42] Therefore, superhabitable exoplanets must be warmer than Earth, yet orbit further out than Earth does and closer to the center of the system's habitable zone.[43][44] This would be possible with a thicker atmosphere or with a higher concentration of greenhouse gases.[45][46]

Star

The star's type largely determines the conditions present in a system.[48][49] The most massive star types (O, B, and A) have a very short life cycle, quickly leaving the main sequence.[50][51] In addition, O-type stars produce a photoevaporation effect that prevents the accretion of planets around the star.[52][53]

On the opposite side, the less massive M-and late-type K-types are by far the most common and long-lived stars of the universe, but their potential for supporting life is still under study.[48][53] Their low luminosity reduces the size of the habitable zone, which are exposed to ultraviolet radiation outbreaks that occur frequently, especially during their first billion years of existence.[15] When a planet's orbit is too short, it can cause tidal locking of the planet, where it always presents the same hemisphere to the star, known as day hemisphere.[54][53] Even if the existence of life were possible in a system of this type, it is unlikely that any exoplanet belonging to a red dwarf star would be considered "superhabitable".[48]

Dismissing both ends, systems with K-type stars (except late-type K stars) and low-luminosity G-type stars, collectively referred to as orange dwarfs, offer the best habitable zones for life.[15][53] K-type stars allow the formation of planets around them, have long life expectancy, and provide stable habitable zones free of the effects of excessive proximity to their stars.[53] Furthermore, the radiation produced by a K-type star is low enough to allow complex life without the need for an atmospheric ozone layer.[15][55][56] They are also the most stable and their habitable zones do not move very much during their lifetimes, so a terrestrial analog located near a K-type star may be habitable for almost all of the main sequence.[15]

Orbit and rotation

Experts have not reached a consensus about what the optimal rotation speed for an exoplanet is, but it cannot be too fast or slow. The latter case can cause problems similar to those observed in Venus, which completes one rotation every 243 Earth days, and as a result, cannot generate an Earth-like magnetic field. A more massive, slow-rotation planet could overcome this problem by having multiple moons due to its higher gravity that can boost the magnetic field.[57][58]

Ideally, the orbit of a superhabitable world would be at the midpoint of the habitable zone of its star system.[59][45]

Atmosphere

There are no solid arguments to explain if Earth's atmosphere has the optimal composition to host life.[45] On Earth, during the period when coal was first formed, atmospheric oxygen (O

2) levels were up to 35%, and coincided with the periods of greatest biodiversity.[60] So, assuming that the presence of a significant amount of oxygen in the atmosphere is essential for exoplanets to develop complex life forms,[61][45] the percentage of oxygen relative to the total atmosphere appears to limit the maximum size of the planet for optimum superhabitability and ample biodiversity.

Also, the atmospheric density should be higher in more massive planets, which reinforces the hypothesis that super-Earths can provide superhabitable conditions.[45]

Age

Planets older than Earth may have greater biodiversity, since native species have had more time to evolve, adapt, and stabilize the environmental conditions suitable for life.[16]

For many years it was thought that older star systems have lower metallicity, and would've therefore formed many fewer planets than newer systems.[62][63] The first exoplanetary discoveries supported this, which were mostly gas giants orbiting very close to their stars (known as hot Jupiters).[64] In 2012, the Kepler telescope's observations suggested this relationship is much more restrictive in systems with hot Jupiters, and that terrestrial planets could form in stars of much lower metallicity to an extent.[63] It's now thought that first Earth-mass objects appeared sometime between 7 and 12 billion years ago.[63]

Profile summary

.jpg.webp)

Despite the scarcity of information available, the hypotheses presented above on superhabitable planets can be summarized as a preliminary profile.[10]

- Mass: approximately 2M🜨.

- Radius: to maintain a similar density to Earth, its radius should be close to 1.2 or 1.3R🜨.

- Oceans: percentage of surface area covered by oceans should be Earth-like but more distributed, without large continuous land masses. The oceans should be shallow; the light then will penetrate easier through the water and will reach the fauna and flora, stimulating an abundance of life down in the ocean.

- Distance: shorter distance from the center of the habitable zone of the system than Earth.

- Temperature: average surface temperature of about 25 °C (77 °F).[12]

- Star and age: belonging to an intermediate K-type star with an older age than the Sun (4.5 billion years) but younger than 7 billion years.

- Atmosphere: somewhat denser than Earth's and with a higher concentration of oxygen. That will make life larger and more abundant.

There is no confirmed exoplanet that meets all these requirements. After updating the database of exoplanets on 23 July 2015, the one that comes closest is Kepler-442b, belonging to an orange dwarf star, with a radius of 1.34R🜨 and a mass of 2.36M🜨, but with an estimated surface temperature of 4 °C (39 °F).[65][66]

Appearance

The appearance of a superhabitable planet should be, in general, very similar to Earth.[67] The main differences, in compliance with the profile seen previously, would be derived from its mass. Its denser atmosphere may prevent the formation of ice sheets as a result of lower thermal difference between different regions of the planet.[45] A superhabitable world would also have a higher concentration of clouds, and abundant rainfall.

The vegetation of such a planet would be very different due to the increased air density, precipitation, temperature, and stellar flux compared to Earth. As the peak wavelength of light differs for K-type stars compared to the Sun, plants may be a different colour than the green vegetation present on Earth.[1][68] Plant life would also cover more of the surface of the planet, which would be visible from space.[67]

In general, the climate of a superhabitable planet would be warm, moist, homogeneous and have stable land, allowing life to extend across the surface without presenting large population differences in contrast to Earth, which has inhospitable areas such as glaciers, deserts and some tropical regions.[38] If the atmosphere contains enough oxygen, the conditions of these planets may be bearable to humans even without the protection of a space suit, provided that the atmosphere does not contain excessive toxic gases, but they would need to develop adaptations to the increased gravity, such as an increase in muscle and bone density.[67][25][69]

Abundance

Heller and Armstrong speculate that the number of superhabitable planets around Kepler 442-like stars can far exceed that of Earth analogs:[70] less massive stars in the main sequence are more abundant than the larger and brighter stars, so there are more orange (K) dwarfs than solar analogues.[71] It is estimated that about 9% of stars in the Milky Way are K-type stars[72] in comparison to 4% of solar analogues.

Another point favoring the predominance of superhabitable planets in regard to Earth analogs is that, unlike the latter, most of the requirements of a superhabitable world can occur spontaneously and jointly simply by having a higher mass.[73] A planetary body close to 2 or 3M🜨 should have longer-lasting plate tectonics and also will have a larger surface area in comparison to Earth.[10] Similarly, it is likely that its oceans are shallower by the effect of gravity on the planet's crust, its gravitational field more intense and its atmosphere denser.[12]

By contrast, Earth-mass planets may have a wider range of conditions. For example, some may sustain active tectonics for shorter time periods and will therefore end up with lower air densities than Earth, increasing the probability of developing global ice coverage, or even permanent Snowball Earth scenarios.[45] Another negative effect of lower atmospheric density can be manifested in the form of thermal oscillations, which can lead to high variability in the global climate and increase the chance for catastrophic events. In addition, by having weaker magnetospheres, such planets may lose their atmospheric hydrogen by hydrodynamic escape easier and become desert planets.[45] Any of these examples could prevent the emergence of life on a planet's surface.[74] In any case, the multitude of scenarios that can turn an Earth-mass planet located in the habitable zone of a solar analogue into an inhospitable place are less likely on a planet that meets the basic features of a superhabitable world, so that the latter should be more common.[70]

In September 2020, astronomers identified 24 superhabitable planet contenders from among more than 4000 confirmed exoplanets at present, based on astrophysical parameters, as well as the natural history of known life forms on the Earth.[75]

Confirmed superhabitable planets

Among the 24 potentially superhabitable planets identified by Schulze-Makuch and colleagues, Kepler-1126b (KOI-2162.01) is currently the only one that has been confirmed.[75] Kepler-69c (KOI-172.02) was initially included before follow-up research showed that its atmospheric composition is likely to be closer to a super-Venus, and thus not superhabitable.[76]

Unconfirmed superhabitable planets

The 22 unconfirmed planetary candidates include:[75]

- KOI-5715.01

- KOI-4878.01

- KOI-456.04

- KOI 5237.01

- KOI 7711.01

- KOI 5248.01

- KOI 5176.01

- KOI 7235.01

- KOI 7223.01

- KOI 7621.01

- KOI 5135.01

- KOI 5819.01

- KOI 5554.01

- KOI 7894.01

- KOI 5276.01

- KOI 8000.01

- KOI 8242.01

- KOI 5389.01

- KOI 5130.01

- KOI 5978.01

- KOI 8047.01

Further reading

Newly confirmed, false probabilities for Kepler objects of interest.

In Search for a Planet Better than Earth: Top Contenders for a Superhabitable World

See also

Notes

- ↑ The habitable zone (HZ) is a region present around each star where a terrestrial planet or moon that has an atmospheric pressure and a suitable combination of gases, could maintain liquid water on its surface.[5][6] However, planets in the HZ may not be habitable, as tidal heating during the planet's orbit can be an additional heat source that causes a planet to enter a runaway greenhouse state.

- ↑ The initials "HZD" or "Habitable Zone Distance" mark the position of a planet about the center of the habitable zone of the system (value 0). A negative HZD value means that the orbit of a planet is smaller near its star —the center of the habitable zone— while a positive value means a wider orbit around its star. The values 1 and −1 mark the boundary of the habitable zone.[43] A superhabitable planet should have a HZD of 0 (the optimal location within the habitable zone).[44]

References

- 1 2 Nancy Y. Kiang (April 2008). "The color of plants on other worlds". Scientific American. 298 (4): 48–55. Bibcode:2008SciAm.298d..48K. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0408-48. PMID 18380141.

- 1 2 3 Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 50

- ↑ Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 51

- ↑ Reynolds, R.T.; McKay, C.P.; Kasting, J.F. (1987). "Europa, tidally heated oceans, and habitable zones around giant planets". Advances in Space Research. 7 (5): 125–132. Bibcode:1987AdSpR...7e.125R. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(87)90364-4. PMID 11538217.

- ↑ Mendez, Abel (10 August 2011). "Habitable Zone Distance (HZD): A habitability metric for exoplanets". PHL. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ↑ "Planetary Habitability Laboratory". PHL de la UPRA. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ Choi, Charles Q. (14 March 2014). "Super-Habitable World May Exist Near Earth". Astrobiology Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Williams, D.M.; Kasting, J.F. (September 1997). "Habitable Planets with High Obliquities". Icarus. 129 (1): 254–267. Bibcode:1997Icar..129..254W. doi:10.1006/icar.1997.5759. PMID 11541242.

- ↑ Rushby, A.J.; Claire, M.W.; Osborn, H.; Watson, A.J. (18 September 2013). "Habitable Zone Lifetimes of Exoplanets around Main Sequence". Astrobiology. 13 (9): 833–849. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13..833R. doi:10.1089/ast.2012.0938. hdl:10023/5071. PMID 24047111.

- 1 2 3 4 Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 59

- 1 2 3 4 5 Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 55

- 1 2 3 Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 55-58

- 1 2 Moyer, Michael (31 January 2014). "Faraway Planets May Be Far Better for Life". Scientific American. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ↑ Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 54-56

- 1 2 3 4 5 Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 57

- 1 2 Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 56-57

- ↑ Cuntz, M.; Guinan, E. F. (2016). "About Exobiology: The Case for Dwarf K Stars". Astrophysical Journal. 827 (1): 79 (9 pp.). arXiv:1606.09580. Bibcode:2016ApJ...827...79C. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/827/1/79. S2CID 119268294.

- ↑ Pierrehumbert, Raymond T. (2 December 2010). Principles of Planetary Climate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521865562.

- ↑ PHL. "Habitable Zone Atmosphere". PHL University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ↑ Clery, Daniel (5 January 2015). "How to make a planet just like Earth". Science Magazine. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ↑ "New Instrument Reveals Recipe for Other Earths". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. 5 January 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ↑ "What Makes an Earth-Like Planet? Here's the Recipe". Space.com. 21 January 2015.

- ↑ Rogers, Leslie A. (2015). "Most 1.6 Earth-radius Planets are Not Rocky". The Astrophysical Journal. 801 (1): 41. arXiv:1407.4457. Bibcode:2015ApJ...801...41R. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/801/1/41. S2CID 9472389.

- ↑ Choi, Charles Q. (17 February 2015). "Planets Orbiting Red Dwarfs May Stay Wet Enough for Life". Space.com. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- 1 2 Howell, Elizabeth (2 January 2014). "Kepler-62f: A Possible Water World". Space.com. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- 1 2 Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 54

- ↑ Chen, Jingjing; Kipping, David (2016). "Probabilistic Forecasting of the Masses and Radii of Other Worlds". The Astrophysical Journal. 834 (1): 17. arXiv:1603.08614. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/834/1/17. S2CID 119114880.

- ↑ Siegel, Ethan (30 June 2021). "It's Time To Retire The Super-Earth, The Most Unsupported Idea In Exoplanets". Forbes. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- 1 2 Noack, L.; Breuer, D. (2011). "Plate Tectonics on Earth-like Planets". EPSC Abstracts. No. 6. pp. 890–891. Bibcode:2011epsc.conf..890N.

- ↑ Gray, John S. (1997). "Marine biodiversity: patterns, threats, and conservation needs". Biodiversity & Conservation. 6 (6): 153–175. doi:10.1023/A:1018335901847. S2CID 11024443.

- ↑ Lewis, Tanya (9 January 2014). "Super-Earth Planets May Have Watery Earthlike Climates". Space.com. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ↑ Van Der Meer, Douwe G.; Zeebe, Richard E.; van Hinsbergen, Douwe J. J.; Sluijs, Appy; Spakman, Wim; Torsvik, Trond H. (25 March 2014). "Plate tectonic controls on atmospheric CO2 levels since the Triassic". PNAS. 111 (12): 4380–4385. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4380V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1315657111. PMC 3970481. PMID 24616495.

- ↑ NASA. "Climate change: How do we know?". Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ↑ Riguzzi, F.; Panza, G.; Varga, P.; Doglioni, C. (19 March 2010). "Can Earth's rotation and tidal despinning drive plate tectonics?". Tectonophysics. 484 (1): 60–73. Bibcode:2010Tectp.484...60R. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2009.06.012.

- ↑ Walker, J.C.G.; Hays, P.B.; Kasting, J.F. (1981). "A negative feedback mechanism for the long-term stabilization of the earth's surface temperature". Journal of Geophysical Research. 86 (86): 9776–9782. Bibcode:1981JGR....86.9776W. doi:10.1029/JC086iC10p09776.

- ↑ Baumstark-Khan, Christa; Facius, Rainer (2002). "Life under Conditions of Ionizing Radiation". Astrobiology. pp. 261–284. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-59381-9_18. ISBN 978-3-642-63957-9.

- ↑ Mayhew, P.J.; Bell, M.A.; Benton, T.G.; McGowan, A.J. (2012). "Biodiversity tracks temperature over time". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (38): 15141–15145. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10915141M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1200844109. PMC 3458383. PMID 22949697.

- 1 2 3 4 Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 55-56

- ↑ O'Neill, Ian (21 July 2014). "Oceans Make Exoplanets Stable for Alien Life". Discovery News. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ↑ Kopparapu, R.K.; Ramirez, R.; Kasting, J.; Eymet, V. (2013). "Habitable Zones Around Main-Sequence Stars: New Estimates". Astrophysical Journal. 765 (2): 131. arXiv:1301.6674. Bibcode:2013ApJ...765..131K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/765/2/131. S2CID 76651902.

- ↑ Perryman 2011, p. 283-284

- ↑ Cain, Fraser (30 September 2013). "How Long Will Life Survive on Earth?". Universe Today. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- 1 2 Mendez, Abel (30 July 2012). "Habitable Zone Distance (HZD): A habitability metric for exoplanets". PHL. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- 1 2 Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 56

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 58

- ↑ Perryman 2011, p. 269

- ↑ PHL. "HEC: Graphical Catalog Results". Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 Schirber, Michael (9 April 2009). "Can Life Thrive Around a Red Dwarf Star?". Space.com. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ "Binary Star Systems: Classification and Evolution". Space.com. 23 August 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ Naftilan, S. A.; Stetson, P. B. (13 July 2006). "How do scientists determine the ages of stars? Is the technique really accurate enough to use it to verify the age of the universe?". Scientific American. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Laughlin, G.; Bodenheimer, P.; Adams, F. C. (1997). "The End of the Main Sequence". The Astrophysical Journal. 482 (1): 420–432. Bibcode:1997ApJ...482..420L. doi:10.1086/304125.

- ↑ Dickinson, David (13 March 2014). ""Death Stars" Caught Blasting Proto-Planets". Universe Today. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Perryman 2011, p. 285

- ↑ Redd, Nola T. (8 December 2011). "Tidal Locking Could Render Habitable Planets Inhospitable". Astrobiology. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Cockell, C.S. (October 1999). "Carbon Biochemistry and the Ultraviolet Radiation Environments of F, G, and K Main Sequence Stars". Icarus. 141 (2): 399–407. Bibcode:1999Icar..141..399C. doi:10.1006/icar.1999.6167.

- ↑ Rushby, A.J.; Claire, M.W.; Osborn, H.; Watson, A.J. (2013). "Habitable Zone Lifetimes of Exoplanets around Main Sequence". Astrobiology. 13 (9): 833–849. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13..833R. doi:10.1089/ast.2012.0938. hdl:10023/5071. PMID 24047111.

- ↑ Choi, Charles Q. (4 November 2014). "Planet Venus Facts: A Hot, Hellish & Volcanic Planet". Space.com. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 57-58

- ↑ Tate, Karl (11 December 2013). "How Habitable Zones for Alien Planets and Stars Work". Space.com. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ↑ Falcon-Lang, H. J. (1999). "156". Fire ecology of a Late Carboniferous floodplain, Joggins, Nova Scotia. London: Journal of the Geological Society. pp. 137–148.

- ↑ Harrison, J.F.; Kaiser, A.; VandenBrooks, J.M. (26 May 2010). "Atmospheric oxygen level and the evolution of insect body size". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Vol. 277. pp. 1937–1946.

- ↑ Sanders, Ray (9 April 2012). "When Stellar Metallicity Sparks Planet Formation". Astrobiology Magazine. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - 1 2 3 Cooper, Keith (4 September 2012). "When Did the Universe Have the Right Stuff for Planets?". Space.com. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ Perryman 2011, p. 188-189

- ↑ NASA. "NASA Exoplanet Archive". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ PHL. "Planetary Habitability Laboratory". PHL University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 54-59

- ↑ Than, Ker (11 April 2007). "Colorful Worlds: Plants on Other Planets Might Not Be Green". Space.com. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ Wall, Mike (18 April 2013). "What Might Alien Life Look Like on New 'Water World' Planets?". Space.com. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 61

- ↑ LeDrew, Glenn (2001). "The Real Starry Sky". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 95 (686): 32–33. Bibcode:2001JRASC..95...32L. ISSN 0035-872X.

- ↑ Croswell, Ken (1997). Planet Quest: The Epic Discovery of Alien Solar Systems (1 ed.). Free Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0684832524.

- ↑ Heller & Armstrong 2014, p. 54-58

- ↑ Johnson, Michele; Harrington, J.D. (17 April 2014). "NASA's Kepler Discovers First Earth-Size Planet in The 'Habitable Zone' of Another Star". NASA. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 Schulze-Makuch, Dirk; Heller, Rene; Guinan, Edward (18 September 2020). "In Search for a Planet Better than Earth: Top Contenders for a Superhabitable World". Astrobiology. 20 (12): 1394–1404. Bibcode:2020AsBio..20.1394S. doi:10.1089/ast.2019.2161. PMC 7757576. PMID 32955925.

- ↑ Kane, Stephen R.; Barclay, Thomas; Gelino, Dawn M. (30 May 2013). "A Potential Super-Venus in the Kepler-69 System". The Astrophysical Journal. 770 (2): L20. arXiv:1305.2933. Bibcode:2013ApJ...770L..20K. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/770/2/L20. ISSN 2041-8205. S2CID 9808447.

Bibliography

- Heller, René; Armstrong, John (2014). "Superhabitable Worlds". Astrobiology. 14 (1): 50–66. arXiv:1401.2392. Bibcode:2014AsBio..14...50H. doi:10.1089/ast.2013.1088. PMID 24380533. S2CID 1824897.

- Perryman, Michael (2011). The Exoplanet Handbook. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76559-6.