| Austrian Armed Forces | |

|---|---|

| Bundesheer | |

Insignia of the Bundesheer | |

| Founded | 18 March 1920 |

| Current form | 15 May 1955 |

| Service branches | Land Forces Air Force Special Forces Cyber Forces |

| Headquarters | Rossauer Barracks, Vienna |

| Website | www |

| Leadership | |

| President | Alexander Van der Bellen |

| Minister of Defense | Klaudia Tanner |

| Chief of the General Staff | Gen Rudolf Striedinger |

| Personnel | |

| Military age | 17 |

| Conscription | 6 months[1] |

| Active personnel | 16,000 |

| Reserve personnel | 125,600[1] |

| Expenditures | |

| Budget | €3,380,000,000 (2023) |

| Percent of GDP | 1.0% (including pensions) (2023)[2] |

| Industry | |

| Domestic suppliers | Steyr Mannlicher Glock Ges.m.b.H. |

| Foreign suppliers | |

| Related articles | |

| History | Military history of Austria Austro-Hungarian Army |

| Ranks | Ranks of the Austrian Bundesheer |

_-_Rossauer-Kaserne_(1).JPG.webp)

The Austrian Armed Forces (German: Bundesheer, lit. 'Federal Army') are the combined military forces of Austria.

The military consists of 16,000 active-duty personnel and 125,600 reservists.[1] The military budget is 1.0% of national GDP (including pensions) or €3.317 billion (2023,without pensions).[3]

History

In 1918, the Republic of German-Austria established a military known as the Volkswehr ("People's Defence"). Volkswehr forces took part in military confrontations with Royal Yugoslav Army troops which occupied parts of Carinthia that Austria claimed as its own. In 1920, after the Republic of German-Austria transitioned into the First Austrian Republic, the new regime changed the military's name to the Bundesheer ("Federal Army"), which it has been known by ever since. In 1938, Bundesheer officers led by Alfred Jansa developed a military operation plan to defend against a potential invasion by Nazi Germany, which ultimately went unused due to a lack of political willpower when Austria was annexed by the Germans in the same year during the Anschluss. Under German rule, the Bundesheer was disbanded, and many Austrians served during World War II in the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS.[4]

World War II role of the "Bundesheer":

- Elements of Austrian Army became 9th Panzer Division (Wehrmacht)

- Elements of Austrian Army became 44th Infantry Division (Wehrmacht)

- 4th Austrian Division became the 45th Infantry Division (Wehrmacht)

- 5th and 7th Austrian Divisions became the 3rd Mountain Division (Wehrmacht)

- 6th Austrian Division became the 2nd Mountain Division (Wehrmacht)

In 1955, Austria issued its Declaration of Neutrality, meaning that it would never join a military alliance. The Austrian Armed Forces' main purpose since then has been the protection of Austria's neutrality. Its relationship with NATO is limited to the Partnership for Peace programme.[5]

With the end of the Cold War, the Austrian military have increasingly assisted the border police in controlling the influx of undocumented migrants through Austrian borders. The war in the neighbouring Balkans resulted in the lifting of the restrictions on the range of weaponry of the Austrian military that had been imposed by the Austrian State Treaty.

Troops entering Klagenfurt after a manoeuvre in Carinthia (September, 1929)

Troops entering Klagenfurt after a manoeuvre in Carinthia (September, 1929) Austrian Gebirgsjäger in 1930

Austrian Gebirgsjäger in 1930 Austrian Armed Forces celebrating their 10th anniversary in March 1930 at the Viennese Heldenplatz

Austrian Armed Forces celebrating their 10th anniversary in March 1930 at the Viennese Heldenplatz Austrian mountain artillerymen during a manoeuvre in Tyrol

Austrian mountain artillerymen during a manoeuvre in Tyrol New "Standarten" (flags) of Austrian Army units being consecrated by a Catholic priest in Mattersburg, Burgenland

New "Standarten" (flags) of Austrian Army units being consecrated by a Catholic priest in Mattersburg, Burgenland Engineers building a bridge across the Danube during a manoeuvre in 1931

Engineers building a bridge across the Danube during a manoeuvre in 1931 Soldiers of the Austrian Army in Vienna, during the Austrian Civil War in 1934

Soldiers of the Austrian Army in Vienna, during the Austrian Civil War in 1934.jpg.webp) Troops training with M1 Garands during the 1950s

Troops training with M1 Garands during the 1950s

Mission

The main constitutional tasks of today's Austrian military are:

- to protect the constitutionally established institutions and the population's democratic freedoms.

- to maintain order and security inside the country.

- to render assistance in the case of natural catastrophes and disasters of exceptional magnitude.

General Organization

.jpg.webp)

Under the constitution, the President is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces.[6] In reality, the Chancellor has the decision-making authority, exercised through the Minister for National Defence.[6] The Chancellor also chairs the National Defence Council, which has as its members a vice-chairman, the minister for national defence, an appointee of this minister, the Chief of the General Staff, and a parliamentary representative.[6] The minister for national defence, acting in co-operation with the minister for interior, coordinates the work of the four major committees under the National Defence Council: the Military Defence Committee; the Civil Defence Committee; the Economic Defence Committee; and the Psychological Defence Committee.[6] The Chief of the General Staff acts as the senior military adviser to the Minister for National Defence, assists the minister in the exercise of his authority, and, as the head of the general staff, is responsible for planning.[6] However, the army commander exercises direct operational control of the Bundesheer in both peacetime and wartime.[6]

Article 79 of the constitution, as amended in 1985, states that the Army is entrusted with the military defence of the country.[6] Insofar as the legally constituted civil authority requests its co-operation, the army is further charged with protecting constitutional institutions and their capacity to act, as well as the democratic freedoms of the inhabitants; maintaining order and security in the interior; and rendering aid in disasters and mishaps of extraordinary scope.[6] In administering the armed forces, the Ministry for National Defence is organized into four principal sections and the inspectorate general: Section I deals with legal and legislative matters; Section II handles personnel and recruitment matters, including discipline and grievances; Section III is concerned with troop command, schools, and other facilities, and it also comprises departments G-1 through G-5 as well as a separate department for air operations; and Section IV deals with procurement and supply, quartermaster matters, armaments, and ordnance.[6]

The general troop inspectorate is a separate section of the ministry with responsibility for co-ordination and fulfilment of the missions of the armed forces.[6] It encompasses a general staff department, an attaché department, and planning and inspection groups.[6]

The armed forces consist solely of the army, of which the air force is considered a constituent part.[6] In 1993, the total active complement of the armed forces was 52,000, of whom 20,000 to 30,000 were conscripts undergoing training of six to eight months.[6] The army had 46,000 personnel on active duty (including an estimated 19,500 conscripts), and the air force had 6,000 personnel (2,400 conscripts).[6]

Army Organization

Cold War

On 1 March 1978, the "Wehrgesetz 1978" became law, which encompassed the "Heeresgliederung 1978" plan to grow the Austrian Armed Forces to 384,000 (84,000 active, 300,000 militia) by the early 1990s to be able to fully employ the Austrian Raumverteidigung concept. A total of 30 new Landwehrstammregimenter were to be raised. On 6 October 1987, the Austrian government enacted the "Heeresgliederung 1987", which instructed the armed forces to stop the growth of the militia at 200,000. Afterwards only the militia's infantry grew, making 1988-1989 the timeframe Austria's armed forces reached their maximum strength. On 29 May 1990 the "Wehrgesetz 1978" was cancelled[7] and the army began to shrink, which accelerated with the "Gesamte Rechtsvorschrift für Wehrgesetz 1990" (Fassung of 31.12.1992).[8]

Raumverteidigung

NATO's Central Army Group in Southern Germany was arrayed against attacks from East Germany and Czechoslovakia, with only the German Army's 10th Panzer Division available to cover the army group's Austrian flank. To strengthen the flank NATO would have deployed the French Army's II Corps, which would have required seven days for mobilization and approach. The arrival of Warsaw Pact forces in southern Bavaria within the first six days after the start of hostilities would have prompted NATO to use tactical nuclear weapons to block the enemy approach routes through Upper Austria.[9] To prevent the use of tactical nuclear weapons on Austrian territory the Austrian military developed the Raumverteidigung (Area Defense) concept, which envisioned that Austrian forces would delay, harass and decimate Warsaw Pact forces with determined, sustained and costly resistance along their expected axis of advance.[9][10][11][12][13]

Strategic considerations

The Austrian military assumed that Warsaw Pact forces would include Czechoslovak People's Army, Hungarian People's Army, and Soviet Army units. A mixed Czechoslovak-Soviet corps of three divisions was expected to mass in the Břeclav-Brno-Znojmo region and attack through the Weinviertel north of Vienna. The expected crossing of the Danube was expected to occur between Tulln and Krems, from where the enemy forces would have turned West to reach the Sankt Pölten area. In parallel the 5th Hungarian Army, consisting of Hungarian units, Soviet Central Group of Forces and Southern Group of Forces units, and Czechoslovak units based in Slovakia was expected to strike from Sopron through the Wiener Wald towards Sankt Pölten.[11][12]

After taking Sankt Pölten the Austrian armed forces expected the combined Warsaw Pact forces to strike West to take possession of the Linz-Steyr-Wels, supported by an advance of two Czechoslovak People's Army divisions through the Mühlviertel to the North of Linz. After taking possession of the Linz basin the Warsaw Pact attack would have continued into Bavaria. The Austrian military also expected an advance by up to three Hungarian People's Army divisions, supported by Romanian People's Army units, into Styria and across the Soboth Pass and Pack Saddle towards Klagenfurt and Villach, from where the Eastern forces could turn South towards the Italian Army's 5th Army Corps or West towards the Italian 4th Alpine Army Corps.[12]

While it was imagined that NATO troops could likewise use Austria as a stepping stone for invasions of the Warsaw Pact countries, such a scenario was considered highly unlikely, unrealistic and eventually remained theoretical in strategic realization.

Initial dispositions

In 1978 the Austrian Armed Forces enacted its new concept of Raumverteidigung. The Raumverteidigung divided the entire nation into Key Zones (Schlüsselzonen), Area Security Zones (Raumsicherungszonen), and Subzones (Teilzonen). Key zones were set up in those areas of the national territory, which an aggressor had to take possession of in order to achieve his military goals. Area security zones were set up to deny an aggressor the possibility to bypass key zones and prevent the massing, movement, supply, and maintenance of enemy units. Operationally the aim was to block the direct march lines through layered defenses in the key zones and to prevent an aggressor from freely using the space in the area security zones through mobile warfare. Both types of zones were to be defended by militia formations.[11][12][14][13]

The four subzones formed the Central Area in Austria's mountainous interior, which was outside of the anticipated main axis of a Warsaw Pact advance. In the event of an attack and an occupation of most of Austria, one or more the sub zones would form the national territory, which would justify the continuation of Austria as a subject of international law. The central area was therefore of essential importance and had to be defended at its entrances. The Army Command and Austrian government would have retreat to a bunker complex in St Johann im Pongau in the central area.[9] Furthermore the central area acted as main depot of Austria's war stocks. The capital Vienna would not have been defended and was therefore excluded from defense preparations.[11][12][13]

Geographically the country was divided into 34 areas:

- 10 Key zones

- 19 Area security zones

- 1 reinforced key area designated Block Zone 33 (Sperrzone 33)

- 4 Sub zones / Central Area

Each key zone and area security zone, and Block Zone 33 were overseen during peacetime by a Landwehrstammregiment, which were tasked with training the militia forces needed for the defense of their assigned zone.[13] The Landwehrstammregiments consisted of a staff company, training companies, a supply train, and mobilization depots. Some of the Landwehrstammregiment also trained and fielded an active Jäger battalion. In case of war the Landwehrstammregiments would have reformed as Landwehr Regiments with various types of militia battalions and companies, allowing the regiments to fight delaying actions from fortified positions as well has hit and run attacks on enemy formations trying to pass through their zone. The Landwehr regiments formed the area-bound Landwehr and fielded the following types of Landwehr units:[11][12]

- Landwehr battalions (Landwehrbataillone) tasked with defending their zone

- Blocking battalions and companies (Sperrbataillone and Sperrkompanien) tasked to man more than 500 bunkers and fortified positions[9]

- Jagdkampf battalions and companies (Jagdkampfbataillone and Jagdkampfkompanien) tasked to fight behind enemy lines and disrupt enemy supply lines

- River-blocking companies (Flusssperrkompanien) tasked with blocking river fords

- Guard companies (Wachkompanien) tasked to guard key infrastructure

- Guard-blocking companies (Wachsperrkompanien) tasked to guard and defend key transport infrastructure, and to prevent the enemy from capturing it

- Stationary artillery batteries (Artilleriebatterie ortsfest) with M2 155mm howitzers in bunkers to lay suppressing fire on enemy approach routes

Operationally the country was divided initially into three operational areas (Operationsraum), which were commanded by the Army Command.[12]

- Operational Area East under Corps Command I, in Graz, encompassing the states of Vienna, Burgenland, Steiermark and Lower Austria, the latter without Key Zone 35

- Operational Area Center under Corps Command II, in Salzburg, encompassing the states of Kärnten, Salzburg and Upper Austria, Key Zone 35, and East Tyrol

- Operational Area West under Military Command Tyrol, in Innsbruck, encompassing the states of Tyrol (without East Tyrol) and Vorarlberg (later merged into Operational Area Center)

The Air Division and army's support troops were under direct Army Command. In wartime the operational commands would command nine brigades, which formed the mobile Landwehr. The mobile Landwehr was the Austrian armed forces reserve, which once the intentions of the opponent were determined, could be used to counterattack enemy formations. The mobile Landwehr consisted of six light Jäger brigades, which would only be fully manned during wartime, and three Panzergrenadier brigades, equipped with main battle tanks and infantry fighting vehicles, which were fully manned at all times. The staffs of the six Jäger brigades would have been formed upon war by the armed forces military commands, which in peacetime had territorial functions in the states. The three Panzergrenadier brigades were assigned to the 1st Panzergrenadier Division and based along the Danube valley from Vienna to Linz.[11][12]

Raumverteidigung Organization

Each Austrian military command was numbered from 1 to 9, with all zones and units assigned to the command or part of the command starting with the same number. The only exception was the 9th Panzergrenadier Brigade, which carried the number of the Vorarlberg Military Command in the extreme West of the country, but was based near Vienna in the East of the country and manned by conscripts from Vienna. The Austrian military commands of the Raumverteidigung concept, their assigned number, zones and main units during peacetime were:[11]

- Burgenland Military Command - No. 1, in Eisenstadt

- Vienna Military Command - No. 2, in Vienna

- 2nd Jäger Brigade, in Vienna (in wartime assigned to Lower Austria Military Command)

- 21st Landwehrstammregiment, in Vienna (Area Security Zone 21 in Lower Austria)

- Lower Austria Military Command - No. 3, in Sankt Pölten

- 3rd Panzergrenadier Brigade, in Mautern an der Donau (based in the Area Security Zone 31)[15]

- 9th Panzergrenadier Brigade, in Götzendorf an der Leitha (based in the Area Security Zone 21)

- 311th Jagdkampfbataillon 311, in Allentsteig (Area Security Zone 31, in peacetime part of the 32nd Landwehrstammregiment)

- 32nd Landwehrstammregiment, in Korneuburg (Area Security Zone 32)

- 33rd Landwehrstammregiment, in Mautern an der Donau (Block Zone 33)

- 34th Landwehrstammregiment, in Wöllersdorf (Key Zone 34)

- 35th Landwehrstammregiment, in Amstetten (Key Zone 35)[16][14]

- 36th Landwehrstammregiment (Area Security Zone 36, formation suspended with the 1987 reform)

- Upper Austria Military Command - No. 4, in Linz

- 4th Panzergrenadier Brigade, in Linz (covering Block Zone 45)

- 41st Landwehrstammregiment, in Steyr (Block Zone 41)

- 42nd Landwehrstammregiment, in Linz (Area Security Zone 42)

- 43rd Landwehrstammregiment, in Wels (Area Security Zone 43)

- 44th Landwehrstammregiment, in Kirchdorf an der Krems (Area Security Zone 44)

- Styria Military Command - No. 5, in Graz

- 5th Jäger Brigade, in Graz

- 51st Landwehrstammregiment (Area Security Zone 51, formation suspended with the 1987 reform)

- 52nd Landwehrstammregiment, in Feldbach (Area Security Zone 52)

- 53rd Landwehrstammregiment, in Straß (Key Zone 53)[17]

- 54th Landwehrstammregiment, in Graz (Key Zone 54)

- 55th Landwehrstammregiment, in Sankt Michael (Subzone 55)

- 56th Landwehrstammregiment (Subzone 56, formation suspended with the 1987 reform)

- Tyrol Military Command - No. 6, in Innsbruck

- 6th Jäger Brigade, in Innsbruck

- 61st Landwehrstammregiment, in Kitzbühel (Area Security Zone 61)

- 62nd Landwehrstammregiment, in Absam (Key Zone 62)

- 63rd Landwehrstammregiment, in Landeck (Area Security Zone 63)

- 64th Landwehrstammregiment, in Lienz (Area Security Zone 64)

- 65th Landwehrstammregiment (Area Security Zone 65, formation suspended with the 1987 reform)

- Carinthia Military Command - No. 7, in Klagenfurt

- 7th Jäger Brigade, in Klagenfurt

- 71st Landwehrstammregiment, in Wolfsberg (Key Zone 71)

- 72nd Landwehrstammregiment, in Klagenfurt (Area Security Zone 72)

- 73rd Landwehrstammregiment, in Villach (Key Zone 73)

- 74th Landwehrstammregiment, in Spittal an der Drau (Area Security Zone 74)

- Salzburg Military Command - No. 8, in Salzburg

- 8th Jäger Brigade, in Salzburg

- 81st Landwehrstammregiment, in Salzburg (Area Security Zone 81)

- 82nd Landwehrstammregiment, in St Johann im Pongau (Subzone 82)

- 83rd Landwehrstammregiment, in Tamsweg (Subzone 83)

- Vorarlberg Military Command - No. 9, in Bregenz

- 91st Landwehrstammregiment, in Lochau (Area Security Zone 91)

Under the area defence strategy, which determined the army's structure until 1993, the army was divided into three principal elements: the standing alert force (Bereitschaftstruppe) of active units, including the 1st Panzergrenadier Division and the air division; the mobile militia (Mobile Landwehr), organized as eight mechanized reserve brigades to be deployed to key danger spots in the event of mobilization; and the stationary militia (Raumgebundene Landwehr) of twenty-six reserve infantry regiments organized for territorial defence.[6] Both the mobile militia and the stationary militia were brought up to strength only in times of mobilization or during periods allotted for refresher training, usually three weeks in June.[6] Training of conscripts was conducted by twenty-eight training and equipment-holding regiments (Landwehrstammregimenter).[6] On mobilization, these regiments would disband, with their cadre reassigned to lead reserve units or form replacement regiments and battalions.[6]

At the army level were a headquarters, guard, and special forces battalions and an artillery battalion at cadre strength.[6] Two corps headquarters, one in the east at Graz and one in the west at Salzburg, would, on mobilization, command the provincially organized units in their respective zones.[6] Each corps included artillery, antitank, antiaircraft, and engineering battalions, and a logistics regiment, all on a cadre basis.[6]

Each of the nine provincial military commands supervised the training and maintenance activities of their training and equipment-holding regiments.[6] On mobilization, these nine commands would convert to a divisional headquarters commanding mobile militia, stationary militia, and other independent units.[6]

The only active units immediately available in an emergency were those of the standing alert force of some 15,000 career soldiers supplemented by eight-month conscripts.[6] The force was organized as a mechanized division consisting of three armored infantry brigades.[6] Each brigade was composed of one tank battalion, one mechanized infantry battalion, and one self-propelled artillery battalion.[6] Two of the brigades had antitank battalions equipped with self-propelled weapons.[6] The divisional headquarters was at Baden bei Wien near Vienna;[6] the 3rd, 4th, and 9th Brigades were based in separate locations, also in the northeast of the country. 3rd Brigade was at Mautern an der Donau, 4th at Linz, and 9th Brigade at Götzendorf an der Leitha.

Post-Cold War structure

The New Army Structure—the reorganization plan announced in late 1991 and scheduled to be in place sometime in 1995—replaces the previous two-corps structure with one of three corps.[6] The new corps is headquartered at Baden, with responsibility for the two northeastern provinces of Lower Austria and Upper Austria.[6] Army headquarters will be eliminated, as will the divisional structure for the three standing brigades.[6] The three corps—in effect, regional commands—will be directly subordinate to the general troop inspector.[6] The three mechanized brigades will be placed directly under the new Third Corps at Baden, although in the future one brigade may be assigned to each of the three corps.[6] The mobile militia will be reduced from eight to six mechanized brigades.[6] Each of the nine provincial commands will have at least one militia regiment of two to six battalions as well as local defence companies.[6]

Total personnel strength—both standing forces and reserves—is to be materially contracted under the new plan.[6] The fully mobilized army will decline in strength from 200,000 to 120,000.[6] The standing alert force will be reduced from 15,000 to 10,000.[6] Reaction time is to be radically shortened so that part of the standing alert force can be deployed within hours to a crisis zone (for example, one adjacent to the border with Slovenia).[6] A task force ready for immediate deployment will be maintained by one of the mechanized brigades on a rotational basis.[6] Separate militia training companies to which all conscripts are assigned will be dismantled; in the future, conscripts will undergo basic training within their mobilization companies.[6] Conscripts in the final stages of their training could supplement the standing forces by being poised for operational deployment at short notice.[6]

Promotion is not based solely on merit but on position attained, level of education, and seniority.[6] Officers with advanced degrees (for which study at the National Defence Academy qualifies) can expect to attain grade VIII before reaching the retirement age of sixty to sixty-five.[6] Those with a baccalaureate degree can expect to reach grade VII (colonel).[6] Career NCOs form part of the same comprehensive personnel structure.[6] It is common for NCOs to transfer at some stage in their careers to civilian status at the equivalent grade, either in the Ministry for National Defence or in the police or prison services after further training.[6]

Austrian Air Force

Austria's air force (German: Luftstreitkräfte) has as its missions the defence of Austrian airspace, tactical support of Austrian ground forces, reconnaissance and military transport, and search-and-rescue support when requested by civil authorities.[6]

Until 1985, when the first of twenty-four Saab 35 Draken were delivered, the country had remained essentially without the capacity to contest violations of its airspace.[6] The Drakens, reconditioned after having served the Swedish Air Force since the early 1960s, were armed, in accordance with the restrictions on missiles in the State Treaty of 1955, only with a cannon.[6] However, following Austria's revised interpretation of its obligations under the treaty, a decision was made in 1993 to procure AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles.[6] The first of these missiles were purchased from Swedish air force inventory, while later a higher performance model was acquired directly from the United States, with deliveries commencing in 1995.[6] French Mistral surface-to-air missiles systems were purchased to add ground-based protection against air attack.[6] The first of the systems arrived in Austria in 1993; final deliveries concluded in 1996.[6]

The Drakens were retired in 2005 and 12 F-5E Tiger II were leased from Switzerland to avoid a gap in the Austrian air defence capabilities until the first Austrian Eurofighter Typhoon units became operational in 2007. Besides one squadron of 15 Eurofighter Typhoons, the air force has a squadron with 28 Saab 105 trainers, which double as reconnaissance and close air support planes.

The helicopter fleet includes 23 AB 212 helicopters used as light transport. 24 French Alouette III are in service as search-and-rescue helicopters. Furthermore, the air force fields 10 OH-58B Kiowa as light scout helicopters. After Austria had to request assistance from the United States Army, Swiss Air Force, French Air Force, and German Bundeswehr to evacuate survivors after the 1999 Galtür Avalanche a decision was taken to equip the Austrian Air Force with medium-sized transport helicopters. Thus in 2002 Austria acquired 9 UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters. In 2003 the air force received 3 C-130K Hercules transport aircraft to support the armed forces in their UN peacekeeping and humanitarian activities.

Special Operations Forces

The Jagdkommando (lit. Hunting Command) is the Austrian Armed Forces' Special Operations group. The duties of this elite unit match those of its foreign counterparts, such as the United States Army Special Forces and British Special Air Service being amongst others counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency. Jagdkommando soldiers are highly trained professionals whose thorough and rigorous training enables them to take over when tasks or situations outgrow the capabilities and specialization of conventional units.

Unit locations

8 Infantry

1 Engineer

1 Cmd Sup

Personnel, conscription, training, and reserves

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Until 1971, Austrian males were obligated to serve nine months in the armed forces, followed by four days of active service every two years for training and inspection.[6] In 1971 the period of initial service was reduced to six months, followed by a total of sixty days of refresher training in the reserves.[6][18] In the early 1990s, about 45,000 conscripts completed their initial military training every year, and 80,000 reservists participated in some form of exercises each year.[6]

Reducing the mobilization strength of the army to 120,000 under the New Army Structure plan is to be accomplished in part by limiting initial training of recruits to six months, followed by reducing the period allotted for refresher training from twenty years to ten years.[6] Each reservist is to receive training over a twelve-day period every second year during his first ten years of reserve duty, generally not extending beyond the time he reaches his mid-thirties.[6] The reduced need for conscripts corresponds to a lower pool of young men because of a declining birth rate.[6] The availability of about 40,000 fit trainees annually in 1993 was expected to fall to barely 30,000 by 2000 and to 26,000 by 2015.[6]

In 2006 conscription was reduced to six months total. Mandatory reserve training was abolished.[19][20][21] Since then the army reserve battalions (Miliz) are suffering from a lack of new reservists and are therefore overaging.

Under a 1974 law, conscientious objectors can be assigned work as medical orderlies, or other occupations in lieu of military service.[6] Exemptions from service are liberally granted—in 1992 about 12,000 persons were exempted, a great increase over the 1991 total of 4,500.[6] The increase occurred after a new law, valid only for 1992 and 1993, no longer required young men to present their objections to the military in a credible way.[6] Previously, that had not been the case.[6] In 1990, for example, two young men rejected by the alternate service commission on the grounds that they did not present their beliefs in a credible manner were sentenced to prison terms of three months and one month, respectively.[6]

Conscripts may attain the rank of private first class by the completion of initial training.[6] Those with leadership potential may serve a longer period to obtain noncommissioned officer (NCO) status in the militia.[6] Those volunteering for the career service can, after three to four years, apply to attend the NCO academy and later a senior NCO course to qualify as warrant officers.[6] Both regular and militia officer candidates undergo a one-year program of basic training.[6] After a further three years, regular officer candidates attending the military academy at Wiener Neustadt and militia officer candidates undergoing periodic intensified refresher training qualify as second lieutenants.[6] The reserve obligation of conscripts generally ends by the time they reach their mid-thirties; NCOs and officers usually end their reserve status at a later age depending on their rank and specialization.[6] By the early 1990s, some 1.3 million men had completed their initial service and refresher training obligations and had no further active-duty commitment.[6]

The military personnel system is an integral part of a comprehensive civil service system.[6] The nine officer ranks from officer candidate through general correspond to grades I through IX of the civil service system.[6] The highest grade, IX, may be occupied by a section chief (undersecretary), a career ambassador, or a three-star general.[6] A grade VIII position may be held by a departmental counselor, a career minister, or a brigadier general.[6] Salary levels are the same for both civil and military personnel in the equivalent grades, although various allowances may be added, such as flight pay or hazardous-duty pay.[6]

The system of promotion in the Austrian military, which offers no incentive for early retirement, means that the military is top-heavy with senior officers.[6] The New Army Structure, which is intended to result in many fewer active-duty and reserve commands, compounds the difficulty.[6] Personnel changes can be implemented only gradually, as the surplus of officers shrinks by attrition.[6] In 1991, the army had four officers of general rank, fifty-nine at the rank of brigadier general (one star), 155 colonels, and 254 lieutenant colonels.[6] The education of career officers is conducted at the Maria Theresia Military Academy at Wiener Neustadt, forty-five kilometres south of Vienna, which was founded in 1752.[6] Young men who have completed their university entrance requirements are eligible to compete for places.[6] The three-year course graduated 212 students in 1990.[6] At the National Defence Academy in Vienna, which has a curriculum comparable to those of the National Defence University and the Army War College in the United States, operational and troop commanders of field-grade rank study for three years in preparation for general staff and command positions.[6] The NCO school is located at Enns near Linz.[6] Troop schools provide continuous specialized courses for officers and NCOs in artillery, air defence, armour, combat engineering, communications, and the like.[6]

In 1998 the Austrian government approved women's membership in the Austrian Armed Forces.[22] All service branches are open for female volunteers. In a public opinion survey in 1988, about 66 percent of those polled approved of opening the military to voluntary service by women; only nine percent favoured obligatory service.[6]

Appearance

Since 2019 the new service uniform with a six colour camouflage pattern is issued, but the old service uniform in olive is still widespread and will be taken out of service very slowly.[23][24][25] The dress uniform is grey; for formal occasions a white uniform may be worn.[6] The air force uniform is identical, with the addition of wings worn on the right jacket breast—gold for officers and silver for enlisted personnel.[6] Branches of service are identified by beret colours: scarlet for the honour Guard; green for infantry; black for armour; cherry for airborne; and dark blue for quartermaster.[6] Insignia of rank are worn on the jacket lapel of the dress uniform (silver stars on a green or gold shield) and on the epaulets of the field uniform (white, silver or gold stars on an olive drab field).[26][27][6]

Equipment

The Austrian military has a wide variety of equipment. Recently, Austria has spent considerable amounts of money modernizing its military arsenal. Leopard 2 main battle tanks, Ulan and Pandur infantry fighting vehicles, C-130 Hercules transport planes, S-70 Black Hawk utility helicopters, and Eurofighter Typhoon multi-purpose combat aircraft have been purchased, along with new helicopters to replace the inadequate ones used after the 1999 Galtür Avalanche.

Rank structure

Of the eight enlisted ranks, only a sergeant (Wachtmeister) or above is considered an NCO.[6] There are two warrant officer ranks—Offiziersstellvertreter and Vizeleutnant.[6] The lowest commissioned rank of officer candidate (Fähnrich)—is held by cadets at the military academy and by reserve officers in training for the rank second lieutenant.[6] To maintain conformity with grade levels in the civil service, there are only two ranks of general in the personnel system—brigadier general (one star) and general lieutenant (three stars).[6] However, the ranks of major general (two stars) and full general (equivalent to four stars) are accorded to officers holding particular military commands.[6]

International operations

Currently (June 14, 2016) there are Bundesheer forces in:

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina

- EUFOR Althea (former SFOR)

- 195 personnel

- since 2 December 2004 under European Union Command

Kosovo/

Kosovo/ Serbia

Serbia

Lebanon

Lebanon

- UNIFIL

- 182 personnel

Croatia

Croatia

- RACVIAC

- 1 personnel

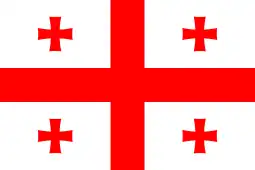

Georgia

Georgia

- EUMM Georgia

- 3 personnel

Cyprus

Cyprus

- UNFICYP

- 4 personnel

Afghanistan

Afghanistan

- RSM

- 9 personnel

EU Mediterranean Sea

EU Mediterranean Sea

- EUNAVFOR MED SOPHIA

- 8 personnel

Lebanon

Lebanon

- UNTSO

- 4 personnel

Armenia

Armenia

- OSCE

- 1 personnel

Central African Republic

Central African Republic

- EUMAM/RCA

- 1 personnel

Congo

Congo

- EUSEC

- 1 personnel

Ukraine

Ukraine

- SMMU

- 10 personnel

Mali

Mali

Western Sahara

Western Sahara

- MINURSO

- 5 personnel

Traditions

Some of the traditions of the old Austro-Hungarian Army continue to be carried on in Bundesheer. For example, the most famous regiment in the Bundesheer is the "Hoch und Deutschmeister Regiment", now known as Jägerbataillon Wien 1 based in "Maria Theresien Kaserne", named after Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. Also nearly every other regiment of the Bundesheer carries on traditions of the famous Austro-Hungarian regiments like "Kaiserjäger", "Rainer", etc.

Strong Europe Tank Challenge

Austria took first place in the Strong Europe Tank Challenge 2017 as six nations and partner nations battled it out in Grafenwoehr, Germany. The Austrian tankers defeated teams from France, Germany, Poland, Ukraine and from the United States in the exercise.[28] The Austrian soldiers used Leopard 2A4 tanks during the competition.[28]

See also

- Austrian conscription referendum, 2013

- Austrian Military Police - Kommando Militärstreife & Militärpolizei (Kdo MilStrf&MP)

- Heeresgeschichtliches Museum

- Heeresnachrichtenamt

- Theresian Military Academy

Citations

- 1 2 3 International Institute for Strategic Studies (25 February 2021). The Military Balance 2021. London: Routledge. p. 85. ISBN 9781032012278.

- ↑ "Mehr Budget fürs Bundesheer" (in German).

- ↑ Landesverteidigung, Bundesministerium für. "Mehr Budget fürs Bundesheer". bundesheer.at (in German). Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ↑ Bischof, Gunter; Pelinka, Anton; Stiefel, Dieter (20 December 2018). The Marshall Plan in Austria: Vol 8. Routledge. p. 323. ISBN 978-1-351-30350-7.

- ↑ "Austrian Mission to NATO". Bundesministerium für europäische und internationale Angelegenheiten. Retrieved Jan 24, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 Tartier, Jean R. (1994). Solsten, Eric; McClave, David E. (eds.). Austria: a country study (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 232–245. ISBN 0-8444-0829-8. OCLC 30664988.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Austrian Official Gazette 1990

- ↑ "RIS - Wehrgesetz 1990 - Bundesrecht konsolidiert, Fassung vom 31.12.1992". www.ris.bka.gv.at. Retrieved Jan 24, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Theuretsbacher, Wilhelm (18 May 2016). "Im Kalten Krieg drohte Österreich atomare Vernichtung". Kurier. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ↑ Seledec, Walter. "Das Bundesheer im Kalten Krieg". ORF - Austrian National TV. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rauchensteiner, Manfried (2010). Zwischen den Blöcken: NATO, Warschauer Pakt und Österreich. Vienna: Böhlau Verlag. pp. 135–192, 325–386, 557–614. ISBN 978-3-205-78469-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lampersberger, Thomas. "Der Weg zur Raumverteidigung 3". Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Steiger, Andreas. "Feuertaufe für die Raumverteidigung - RVÜ79". Truppendienst. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- 1 2 Gerold Keusch, Rudolf Halbartschlager. "Das entscheidende Gelände der Raumverteidigung 1". Truppendienst. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ↑ "Die Geschichte der 3. Panzergernadierbrigade" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ↑ Häusler. "Geländebefahrbarkeit der Schlüsselzone 35" (PDF). Geologischen Bundesanstalt. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ↑ 160 Jahre Garnison Straß (PDF). Bundesministeriums für Landesverteidigung und Sport. pp. 42–45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ↑ Tomanović, Milutin, ed. (1972). Hronika međunarodnih događaja 1971 [The Chronicle of International Events in 1971] (in Serbo-Croatian). Belgrade: Institute of International Politics and Economics. p. 2723.

- ↑ "Military service age and obligation - The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ↑ "Neutral Austria votes to keep military draft". Reuters. 2013-01-20. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ↑ Wasinger, Matthias (2020). "From Strategy to Military Capability: the Austrian Example". Military Strategy Magazine. 7 (2): 40–45.

- ↑ Turner, B. (29 December 2016). The Statesman's Yearbook 2001: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World. Springer. p. 907. ISBN 978-0-230-27129-6.

- ↑ Landesverteidigung, Bundesministerium für. "Verteidigungsminister Mario Kunasek übergibt neue Tarnuniform an die Truppe". bundesheer.at. Retrieved Jan 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Neue Tarnuniformen: Ab heute ist Bundesheer in Camouflage-Look im Einsatz". 4 March 2019.

- ↑ "Österreich: Neue Tarnuniformen". 3 March 2019.

- ↑ BMLVS - Abteilung Kommunikation. "Bundesheer - Uniformen und Abzeichen - Barettfarben". Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ BMLVS - Abteilung Kommunikation. "Bundesheer - Uniformen und Abzeichen - Dienstgrade". Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- 1 2 "Austria takes top honors in Strong Europe Tank Challenge". www.army.mil. Retrieved Jan 24, 2023.

References

- IISS (2019). The Military Balance 2019. Routledge. ISBN 978-1857439885.

- CIA World Factbook, 2005

- Christopher Eger, The Final End of the Austrian Navy, on the site militaryhistory.suite101.com, 2006

.svg.png.webp)