Azerbaijani–Mongolian cultural relations (South Azerbaijani: آزربایجان–مونقول مدنی الاقلری, Mongolian: ᠠᠽᠧᠪᠠᠢᠵᠢᠶᠠᠩ ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠤᠯ ᠰᠣᠶᠣᠯ ᠤᠨ ᠬᠠᠷᠢᠴᠠᠭᠠ) started in 13th century with the Mongolian invasion of the areas currently populated by Azerbaijanis. Turkic and Mongolian migration to the area during the Ilkhanate era played major role in forming Azerbaijani people. During the time, Mongols migrated to the area converted to Islam and turkified. In this period Azerbaijani was called "Turkic of our state" by Ibn Muhanna's dictionary. Literatures were written in this language.

During the period of Ilkhanates Shamanist traditions became stronger and lived in folklore, culture, and mythology. In this era, process of conversion to Shia Islam in Iran and Azerbaijan has started. Later on, this became the base for the formation of Turcoman-shia states like Qara Qoyunlu and Safavids.

Orders of Ghazan and Öljaitü khans' and Genghis Khan's laws (Yassa) were used together with Islamic Sharia. During the period of Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu, Azerbaijani Turks considered those Yassas as their national law and remained loyal to it. Ilkhanates applied the Uighur variant of the twelve-animal calendar, which was used until the fall of Qajars. There are toponyms from the Mongol period in the territory of modern Azerbaijan. The "Karabakh" toponym, which is used to name the south of the historical territory of Arran, appeared in this period. In addition to the dialects of the Azerbaijani language, words borrowed from the Mongolian language are also observed in the areas of Eastern Anatolia belonging to the Azerbaijani dialect environment.

Historical and cultural environment

From 1256 to 1335 Ilkhanates, and from 1335 to 1337 Chobanids from sulduz tribe were in the region.[2] Mongolian and Turkic noblemen owned the role of political administration in Ilkhanates state. Part of the local Iranian nobility was destroyed. Their lands either seized by the state or Mongolian noblemen. Ilkhanates kept being nomads.[3]

The reason of the unity between Turkic and Mongolian elements in states emerged after the fall of Mongol Empire was nomadic heritage and thousand year long symbiosis in central Asia. At some point Turkic population and military strength were stronger than Mongols. Ilkhanates used Eastern Turkic despite Western Turkic (Oghuz) was spoken in the areas they controlled. Since Seljuks used Arabic and Persian in official documents, the first use of the Turkic language in official documents in Iran was due to the Mongols. After accepting Islam, most of the Mongols assimilated not to the Persians, but to the Turks, to whom they were culturally closer. Turcomans, who were more numerous than the Mongols and were Muslims, quickly lost the Mongols in their midst due to their shared nomadic lifestyle. In fact, the Islamization of Mongols was one of the aspects of Turkification.[4]

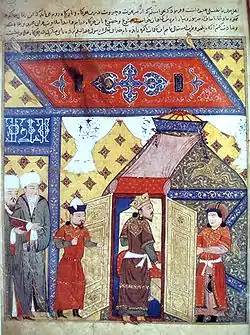

Hulagu Khan's vizier Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was completely familiar with the Turkic and Mongolian language and script as well as Mongolian and Easter Turkic customs, culture, and traditions. His son also became completely Turkic. The spoken language of vizier Rashid al-Din Hamadani and his sons, who was originally a Jew, was Turkic. He also knew the Mongolian language perfectly. Although his works reached the modern era in Arabic and Persian, he knew how to write in Turkic and Mongolian languages and adopted Turkic customs and traditions. The daughters of Rashid al-Din and his son Ghiyath al-Din were nicknamed "khatun" in Turkic, and one of Rashid al-Din's grandsons was named Artug.[5]

Formation of Azerbaijanis

At the same time as the Turkification of Azerbaijan during the Mongol period, the process of Turkification of the Mongols living there took place, the second process had a positive effect on the first process.[6] The Mongols who accepted Turkism and Islam were a group that spoke Turkic, but had Mongolian historical memory and continued their nomadic life in Iran, Azerbaijan and Eastern Anatolia. Turko-Mongolian nomads did not lose the military characteristics that are an important function of nomadic life.[7]

The settlement policy of the Turko-Mongolian tribes

The conquest of the region by the Seljuk Turks in the 11th century and the influx of Turkic peoples in the following centuries, including the Mongol invasions in the 13th century, led to Turkification in the area where Azerbaijanis currently live. Most of the tribes that formed the Mongol armies, as well as those who were forced to migrate as a result of the Mongol invasions, were Turks.[9] Turkologist Zeki Velidi Togan estimates the number of Turkic-Mongolian tribes that came to Azerbaijan as 2 million people according to primary sources.[10] Nevertheless, it is thought that the physiology of Azerbaijanis is not related to the Mongolian race.[11]

Turks made up a large part of the army of the Ilkhanates, the fifth Mongol nation.[12] Hulagu and his son Abaqa Khan strategically relocated scattered Turkic and Mongolian people to designated areas in Azerbaijan, northern Iraq, and Anatolia during their rule. This intentional resettlement and portraying local Muslim Oghuz nomads as khans and rulers paved the way for consolidation Azerbaijani Turkic identity.[13] In the gradual Turkification of Iranian Azerbaijan, the policy of the Ilkhanates to give land shares (iqta', soyurgal) to the leading military leaders played a role. The presence of the khans themselves and their entourage, and then the Turkoman followers starting with the Jalayirids, as well as the nomads who came from Central Asia with Emir Timur, in these mountainous pasture areas was another factor.[14] As a result, the territory of Azerbaijan and Iraq-i-Ajam became a yaylak and kishlak for 2 million nomads.[15]

During the Mongol period, Turkification was clearly observed in South and North Azerbaijan. Hamdallah Qazvini mentions the Turkic settlements here, and Ibn Battuta speaks about the importance of Tabriz Turks. A number of Turkic and Mongolian tribes were moved to the Mughan Plain during the Ghazan Khan's period. The rest of those tribes were met by Adam Olearius in 17th century. Nizari mentions in his work that the Arran region was overflowing with the army of the Turks (Ilkhanate warriors).[8] After the Ilhanates, during the Jalayirids, Timurids, Qara Qoyunlus and Ak Qoyunlus, the Mongols became Turkic, and the Turkic population increased in Iraq, North and South Azerbaijan.[16]

Although Zakariyya Ghazvini writes that the Turks who lived in the area before the Mongols were removed from the region, in the opinion of Sheikh Safiaddin Ardabili, it is believed that the Turkomans and Kurds in the country remained in their previous places. In any case, the Turks who lived here from the beginning (Seljuk Turks) gave the good territories to the Mongols and Eastern Turks and moved to other parts of the country.[17]

Settlement regions of tribes

As in the past (Seljuq period), during the Ilkhanate dynasty, Northern Azerbaijan was in the first place in the settlement of Turks and Mongols. In Iranian Azerbaijan, especially around Maragha, Khoy, and Urmia lake had also settlement process as well as Ajam-i-Iraq, the city of Sultaniyya, built between Qazvin-Zanjan, and its surroundings, and partially Ray region.[6]

During the Mongol period, Qajars lived in Khalkhal, Turgais (from the Ilkhanate) in Maragha, Kipchaks and Oirats in Ardabil, Yıvas in Khoy, and Imirs (Amarlu) in the Ghezel Ozan (Gizil Uzan) between Ardabil and Gilan. Even after the invasion of Timurids, part of Ilkhanates continued to live in Maragha. Around Hamadan and in the city, the Qara Qoyunlu people, especially Baharlı branch, formed an important Turkic population.[8] The main parts of Javanshirs, Ak Qoyunlus and Qara Qoyunlus came from Turkestan to Anatolia and Azerbaijan during the Ilkhanate dynasty.[18] Among the Turkoman living in Mughan and Arran, the tribe with the most livestock was Chobanli, which was known to have lived during the Jalayirid period.[19]

Oirats, a Turko-Mongol tribe, were settled in Sheki and Shamakhi region, which was the most powerful and numerous tribe in the Kura basin in its time.[20] The reason Oirat, Garagali, Kharkhatan, Gegir, Orand and Laladulan tribes settled in Lankaran, Neftchala and Lerik regions may be due to the similarity of these regions to Mongolia.[21]

It is belived that the reason for placing Kunjut, Junud, Baydarli, and Tangit tribes in Sheki and Qakh areas, which were the borders of Ilkhanate and Golden Horde, was that these tribes had to protect the border against the Golden Horde with their good fighting skills.[21]

Bayats came to Azerbaijan in 13th century with the Mongol invaders.[22][23] Padar tribe was settled in Azerbaijan during the Ilkhanate period. According to one of the claims about the origin of their name, the name "padar" is a phonetic distortion of the name of Chagatai Khan's son Baidar.[24]

It is believed that Qajars, came to Iran in the 13th century, and then to the South Caucasus,[25] was one of the Turkic tribes in Hulagu Khan's army.[26] There is a legend that the name of the Qajar comes from the Mongol leader Qajar Noyan.[27] According to Mirza Hasan Zonuzi Khoyi, the origin of the Qajar is Turkestan Mongols.[28] However, other sources think that the Qajars did not come from the Mongols, but from the Khazars.[29][30]

Toponyms

All court ladies (khavatin), princes, generals (umara), pillars of power and courtiers gathered in Karabakh of Arran and without any pretext or hypocrisy agreed the authority of the Islamic ruler (Gazan Khan').

Since the 13th century, place names of Mongolian origin began to appear in Azerbaijan.[31] Other areas bearing the traces of Mongol era tribes are Xançobanlı, Cəlayir, Kurqan, Küngüt (Aşağı və Baş Küngüt), Cunud, Tanqıt, Elciqan, Uriyad, Onqutlu, Tatar, Tatarlı, Xarxatan, Aratkənd, Çirkin, Damğalı, Dolanlar, Alar.[32]

The city of Salyan was called "Dalan-Navur" in Mongolian.[20]

Some of the toponyms seen in historical works, starting with Hulagu Khan and especially Abaqa Khan, are in Turkic, and some are in Mongolian. Lake Sevan in Armenia, which Azerbaijanis call Goycha (Azerbaijani: Göyçə), was called "Kokcha sea" during the rule of Abaga Khan.[33] Some Mongolian place names had Turkic and Persian words used together at first, but later on Persian words were gradually forgotten.[6]

From 15th century (Mongol period), the southern part of Arran began to be called "Garabagh" (Azerbaijani: Qarabağ, lit. 'Black garden'). The word "qara" is of Turkic origin, and "bağ" is of Persian origin.[34][35]

| Place | Tribe | Origin | Belongs to |

|---|---|---|---|

| Khalkhal | Qajars | Turkic | |

| Maragha | Turgays | ||

| Ardabil | Kipchaks and Oirats | Turkic and Mongolian | |

| Khoyda | Yıvas | Turkic | |

| Gizil Ozan | Imirli | ||

| Hamadan | Qara Qoyunlu (Baharlu) | Turkic | |

| Anatolia and Azerbaijan | Javanshirs, Aq qoyunlus and Qara Qoyunlus | Turkic | |

| Sheki and Shamakhi | Oirat | Mongolian | Jalayirs |

| Qakh | Baydarly, Tangyt | Mongolian | |

| Aşağı və Baş Küngüt, Künkütçay | Kingli | Mongolian | |

| Cunud | Sunnit | Mongolian | |

| Lankaran, Neftçala and Lerik | Oirat, Qaraqaşlı, Xarxatan, Orand | ||

| Köhnə Gəgir və Gəgiran | Kikir | ||

| Sumgaıt, Corat və Ələt | Suqaut, Corat və Ələt | Mongolian | |

| Aşağı Bucaq | Bucaq | Mongolian | Nogai |

| Çeşməli (Tovuz) | Çirkinlilər | Mongolian | |

| Darğalı (Qəmərli) | Damğalı | Mongolian | |

| Dolanlar, Lələdulan, Əvçədulan | Dolanlar | Mongolian | |

| Günnüt | Günnüt | Mongolian | |

| Üngütlü | Ongut | Mongolian | |

| Oncallı (Qax) | Onja (Əncə) | Turkic | Kipchaq |

Sources: [21]

Language

According to Zeki Velidi Togan, the main norms of the Azerbaijani language during the Mongolian dynasty – Ilkhanate period were formed as a result of the mutual influence of the Turkic languages – Oghuz-Turkmen, Kipchak and East Turkestan. The author notes that in the first half of the 14th century, when Ibn Muhanna was compiling the dictionary of Turkic and Mongolian languages spoken during the Ilkhanate period, he mentioned "Turkic language of our country" (Turki arzina) in addition to "Turkmen" and "Turkistan language". The examples attributed to "the Turkic language of our country" in the dictionary can be considered the first examples of the Azerbaijani language.[1] According to experts such as P. M. Melioranski, Bekir Chobanzade, and Ahmad Jafaroghlu, the Azerbaijani language is meant here.[36]

According to Fuat Köprülü, new Turko-Oghuz tribes, who came from the East to West (Azerbaijan and Eastern Anatolia) as a result of Mongol invasions, added new elements to language of Oghuz people (Turkmans/Turkmen) who settled here earlier during the Seljuk period.[37]

In all forms of the Azerbaijani language there are words borrowed from Mongolian language: yekə (big), qadağan (prohibited), qayçı (scissors), nöqtə (dot), hündür (tall), keşik (guard). These loanwords represent a common Ilkhanate heritage (1256–1335). Unlike Azerbaijani Turkish, Anatolian Turkish does not have such loanwords taken from the Mongolian.[38] In addition, words borrowed from the Mongolian language can be found in the dialects of the Azerbaijani language belonging to the Shirvan region. It is extralinguistic in nature and closely related to historical events.[39]

Literature

Folklore & mythology

.jpg.webp)

Mongol invasion and the Ilkhanate rule over both Iranian Azerbaijan and modern Azerbaijan in the subsequent periods led to strengthening of the Shamanistic customs spread there. The customs of Shamanism have undergone changes under the influence of Islam. Some of them have been preserved. The rules of ancient traditions have continued to live in cultural environment of Azerbaijan – in children's folklore and games, ceremonies and beliefs of people. For example, the aş eaten by Azerbaijanis on Thursdays in honor of the spirits of the dead is an ancient form of Shamanism.[40]

It is believed that saya is a Shamanic god and that Sayanism originated in Azerbaijan. The connection between saya and the words Yaya, Dz'aya and Dzayagg mean god in Mongolian shows that saya comes from Shamanism. The belief about saya came to the Altai, and from there to Anatolia and Azerbaijan under the influence of the old shaman Turko-Mongolian cultural environment.[41]

In Maragha, the first capital of the Ilkhanate state, there is a stone-hewn tomb dating back to the Mongol period. The building is deeply connected with Mongolian burial customs. The name of the village where the tomb is located is Varoy in local Azerbaijani literature. This name is linguistically similar to the village of Varay (Viyar) located in Sultaniyya, which was the Elkhani capital in last years of the state. The name of both villages is close to the word Vara given in Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk by Mahmud Kashgari. According to dictionary the word is connected with the myth of the separation of earth and sky. The roots of this expression may go back to religious beliefs about death. The words Varoy and Varay may be words that have been preserved in the Turkic language throughout history and have survived to the present day.[42]

Azerbaijani researchers Mammadhuseyn Tahmasib and Məmmədağa Sultanov claimed that the folklore hero Molla Nasraddin was the minister of the Ilkhanate period, Nasreddin Tusi. The reasons for this are that they lived in the same period, Tusi included anecdotes in one of his works, ridiculed astrologers as a scientist, Molla Nasraddin went to Emir Timur as a representative of the country, the parallel between Nasraddin Tusi being sent to Hulagu Khan by the ruler of Alamut, and both of them having the same name – Hasan. However, Mammadhuseyn Tahmasib stated that this information is not a substantial evidence, but just an allegation.[43][44]

Tapdig Goy oglu, the hero of an Azerbaijani fairy tale and son of Tufan Div, was expelled from heaven to earth. He is part of a legendary group of heroes, akin to God's children in Turkic and Mongolian legends, sent to cleanse the earth of demonic forces.[45][46] In another Azerbaijani tale, princes throw apples to girls to choose their betrothed, a custom that existed among the Mongols living in Azerbaijan in the 17th century.[47]

Written literature

The beginning of written classic Azerbaijani Turkic literature coincides with the period after the Mongol invasion.[48][49] The development of a special style of Azerbaijani poetry between 13th and 14th centuries was partly related to the Eastern Turkic traditions brought to the region from Khorasan during the Mongol period.[48] One of the reasons why Azerbaijanis created their own literature and played a role in its independent evolution was the fact that there were more Turkic and Mongolian elements in Azerbaijan than in Anatolia.[50]

At the beginning of the 14th century, the historian Vassaf wrote verses in Azerbaijani Turkic and mixed them with Eastern Turkic spelling. While the words in the Turkic in the works of Nasiraddin Tusi correspond to Eastern Turkic, the words in the works of Hamdullah Qazvini are in the Azerbaijani dialect. There are prayers, sermons and religious verses written in a Turkic language, which is a mixture of Eastern Turkish and Azerbaijani Turkic, dating back to the first half of the 14th century. In the second half of the 14th century, in Azerbaijan, on the one hand, the works of Khwarazm and Transoxian Turkic poets, including Khujandi, were read, and on the other hand, works were written in Azerbaijani Turkish based on these themes. Among them, Imadaddin Nasimi, Gazi Burhanaddin and Mustafa Zarir from Salur Turks can be mentioned.[1]

Works in Azerbaijani Turkish developed during the period of Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan (1316-1335). The fact that the Azerbaijani language takes a leading place together with Uyghur is evident from the information in the historical works and from the fact that Ajam poets used words from these two languages in their works.[1]

The literary trend that developed during the Mongol period included the Jalayirid ruler Sultan Ahmad. The fact that Sultan Ahmad wrote poems in Turkic is confirmed in the work of Abul Mahasin Yusif Bey Tanribirdi "Al-Nujum al-Zuhirra". The ghazal he wrote shows that Azerbaijani Turkish was used as a literary language in the Jalairid palaces.[51] Sultan Ahmad's ghazal ensured the continuity of Turks and the Turkic language, which prevailed in Jalayirid-Turkic identity fusion.[52]

Music

Sultan Ahmad highly appreciated the musicologist Abdulgadir Maraghayi. Maraghayi had two small couplets in Azerbaijani language. These are called tuyugh and koshuk. It is said that the song was composed for Emir Timur and was sung in front of him. These verses written by Maragayi in Azerbaijani demonstrate the role of the Turkic language in musical gatherings.[51]

Social life

Religion

We are of the same lineage (origin). These alans are not related by lineage to you so that you should not help them. And their religion is not similar to yours. If you do not stand between them and us, we promise not to touch you. And we will give you as much money and clothes as you want.

Deal between Mongols and Kipchaks in "The Complete History" by Ibn al-Athir

Shamanic rites were performed in the palace of Hulagu Khan and his son Abaga Khan during the Ilkhanate period. The performed rites influenced Turkic Sufis in Anatolia and Azerbaijan.[53]

Azerbaijan served as a showcase for Buddhist methods and material culture.[54] The Ilkhanates used their wealth to create gold and silver forms of Buddha in Azerbaijan and Khorasan.[55] Hulagu Khan built a prominent Buddhist temple in Khoy. The territory of Khoy was called "Turkic country"[n 1][56] because of the khitay (Chinese) population who came from Uyguristan. This suggests the presence of an immigrant Buddhist population that settled in the area by choice or/and on purpose. They were associated with early Buddhist temple construction in the region and provided masters and students for the project.[57]

Ahmdd Tekuder Khan, the son of Abaga Khan, was extremely interested in Turkic sheikhs. While wintering in Arran, he engaged in sama (musical zikr) in house of a Turkic sheikh named Ishan Mengli. The entry of Jalal ad-Din Rumi into the path of spiritual dance and attraction occurred through a dervish from Tabriz, after witnessing the influence of Turkic Sufi masters. Turkic Sufis of Azerbaijan also managed to win the hearts of the Seljuks in Konya. In addition, as Ibn Batuta noted, it is assumed that Azerbaijani, Anatolian and Khorasan Turkic veterans who built camps around Crimea and lived on war products participated in the campaigns of Nogai Khan, the army general of the Golden Horde.[58]

The Rifiyyah (Ahmadiyya) sect, spread in Iraq, Azerbaijan, Anatolia and even in Golden Horde, benefited from Mongolian shamanism. Mongols used their Sufi role to gain influence in the Islamic environment.[59] The Mongol army fought against supersticious sects (e.g. Javvaliqi) and protected Turkic Sufis such as Bektashi and Baraghi. Superstitious sects wanted to slander the rites of Turkic dervishes by calling them "the work of the devil". Azerbaijan is also among the territories where Javaliqis are dispersed in a distraught and miserable manner.[60]

During the Ilkhanates period, the conversion to Shiism, which would continue for a long time, began in Iran and Azerbaijan. During this period, the base of Turkoman-Shiite states such as Qara Qoyunlu and Safavids was formed. The theological works written by Shia scholars, including Nasraddin Tusi, Allama al-Hilli, Ibn Tawus, etc., which came out of Shia madrasas, are one of the factors that promote the spread of Shiism in the region. By the time the last Ilkhanate ruler, Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan, died, the Shiite population had begun to reach 20 percent of the empire's population.[61]

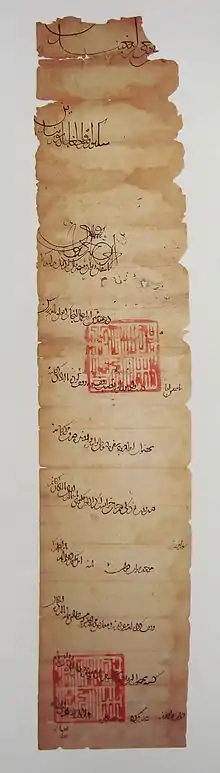

Law

Although the Ilkhanates accepted Islam, they did not stop the execution of the laws (Yassa) of Genghis Khan due to the decisions of the period of Öljaitü and Özbeg Khan. Ghazan Khan also took into account the decision to follow Islamic Sharia and Genghis Khan's Yassa together. Azerbaijani and Eastern Anatolian Turks considered the laws of Yassa as their national law during the period of Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu and remained loyal to it.[62]

Rashid al-Din Hamadani's sons Giyasaddin and Jalaluddin were praised and loved by the Turks for their virtues and morals, and for their knowledge of Ilkhanate laws and regulations.[5]

Later, Anatolian Turks considered themselves citizens of Ilkhanate and obeyed its laws. The Azerbaijani poet of the Timurid period, Gazi Burhanaddin, wrote that the force that could force him to do something, just as his lover could do, was the yassa and the khan's friendship, the identity card he knew was the khan's stamp, the state system he knew was khagan, ulu khan, sultan, bey, tutgavul (a security system to protect caravans and roads).[63]

In Iraq-i-Ajam and Azerbaijan, Mongols and Eastern Turks were not engaged in agriculture, so they employed farmers in their territories. In addition, the princes of Juji and Chagatai receive taxes from their hereditary (inçü) lands in Azerbaijan, and this did not change even though the war with the Ilkhanates continued.[64]

Calendar

During the Ilkhanate dynasty, all Turkoman Oghuz clans of Azerbaijan and Eastern Anatolia used Turkic year and month names.[65] The use of the 12 animal calendar was due to the influence of Eastern Turkic, and the Mongols adopted the Uighur version of the calendar. Although Mongolian translations were used, Turkish names have retained their importance. In Rashid al-Din Hamadani's historical work, year names are used 26 times in Turkic and 34 times in Mongolian. The names of the months were only in Turkic. In Iran, the Turko-Mongolian animal calendar was used together with the Hijri calendar from the end of the Mongol rule until the fall of Qajars.[66]

Nobility

I. P. Petrushevsky's research shows that Buddhists and Nestorians were often allied at Ilkhanate palace, while the Muslim elite, supported by factions of the Turkic military aristocracy and Iranian bureaucrats, opposed them. Sometimes the Jews sided with Buddhists.[67]

In the 13th-15th centuries, the lands of the old feudal lords in present-day Azerbaijan and Armenia gradually passed into the hands of the hereditary heads of the nomadic tribes.[68] The Orlat dynasty, which ruled the Sheki rulership that arose at the end of the 14th century, was an Azerbaijanized Turkic-speaking Mongol dynasty. Two members of this dynasty are known – Seyyid Ali Orlat (ca. 1393 – 1399) and Seyyid Ahmad Orlat (1399 – 1423/1424).[69][70][71] Darğalar village is located in the Barda region of Azerbaijan. It is believed that the village was founded by Mongol tax officials, descendants of the Dargas, and took its name from them.[21]

Nökər is a title historically used for members of the noble class in Mongol states.[72] It is one of the warrior classes that existed in Turko-Mongol societies in Middle Ages. Translated from the Mongolian language, it means "companion", "warrior", "servant", "helper" and "slave". Amongst Turks, this expression is used in the sense of a groom or groom's son's companion.[73][74] The title of servant also existed in Azerbaijan.[72] This title can be found in the Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu states as well.[74] Evliya Çelebi notes that the khanates of Baku, Ganja and Iravan had a certain number of servants.[72] In the military unit of the Kangarli cavalry during the Russian Tsarist period, soldiers and nokars came after gentlemen, viceroys and lawyers. The servants of the Kangarli cavalry had a special mark on their collars.[75] The word "nökər" is a name given to a male servant in the modern Azerbaijani language.[72]

The dynasties that replaced the Ilkhanates (Jalairs, Chobanids, Timurids, Aq Qoyunlus, Safavids, Afshars, Qajars) implemented the system of administration of Iran by Turko-Mongolian nomadic political and military elite. Nader Shah, the first ruler of the Afshar dynasty, held a congress in Mughan according to the Turko-Mongol tradition and thus became the ruler. He ordered his poets to write poems about him repeating the conquests of Genghis Khan. The Azerbaijani-speaking[76][77] Qajars claim that the beginning of their dynasty came from Qajar Noyon, the son of a Mongol commander, and hung paintings of Genghis Khan in Qajar-style clothes in their palaces.

Culinary

The "Yinshan zhengyao", a court recipe book of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1330s), was inspired by Inner and Western Asia. Azerbaijani cuisine includes elements similar to the foods found in this cookbook. An example of such dishes is piti. The piti dish of Azerbaijan is similar to the harissa dish of Iraq, and thus to a number of recipes in the Mongolian book. Quince is also added to Azerbaijan's bozbash dish, as is often done in "Yinshan zhengyao". Jams and sherbets of Azerbaijani cuisine are reminiscent of Turkic and Eastern cuisines and "Yinshan zhenqiao" recipes.[78] The roots of the kebab dish prepared in Azerbaijani, Iranian and Russian cuisine go back to the time when the territory of these countries lived as a part of the old Mongolian civilization.[79]

Cultural heritage in modern era

The Garabaghlar tomb complex, located in the Kangarli district of Nakhchivan, belonging to the Ilkhanate era, includes a tomb, a double minaret, and the remains of a religious building located between these two monuments. It is written in the inscription: "The construction of this building was ordered by Jahan Qudi Khatun". Qudi Khatun is believed to be Qutui Khatu, the wife of Ilkhanate ruler Abaqa.[80]

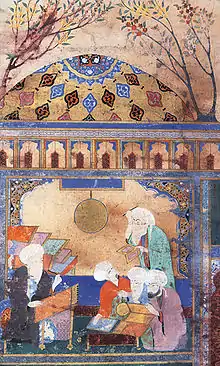

Traces of archaic traditions created by artists working in the workshops of Ilkhanate vizier Rashid al-Din at the beginning of the 14th century can also be seen in the miniatures of the 15th century Baku artist Abdul Bagi Bakuvi. Bakuvi's "Horse and its Master" is an Islamic version of a warrior image that was very popular in China during the late Yuan and early Ming dynasties.[81][82]

Gallery

A pottery plate from the Ilkhanate period discovered in Beylagan

A pottery plate from the Ilkhanate period discovered in Beylagan.JPG.webp) Remains of silk fabric from the Ilkhanate era (13th century)

Remains of silk fabric from the Ilkhanate era (13th century)

See also

Notes

- ↑ Khoy area is called "Iranian Turkestan" because Turks live here. These Turks most likely settled in the region before the Mongols. See: Yakupoğlu, 2018. pp. 188–189

References

- 1 2 3 4 Togan 1981, p. 272.

- ↑ Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "CHOBANIDS". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2021–06–22.

- ↑ История Ирана с древнейших времен до конца XVIII века. — Л.: Изд-во ЛГУ, 1958. — 390 с. p 190

- ↑ István Vásáry. The role and function of Mongolian and Turkic in Ilkhanid Iran // Turcologia.

- 1 2 Togan 1981, p. 282.

- 1 2 3 Sümer 1957, p. 439.

- ↑ Durand-Guédy 2010, pp. 376–377.

- 1 2 3 Köprülü 2000, p. 24.

- ↑ Suny, Ronald Grigor , Silaev, Evgeny Dmitrievich , Howe, G. Melvyn and Allworth, Edward. "Azerbaijan". Encyclopedia Britannica, 1 Jun. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Azerbaijan Archived 2019-07-02 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 10 June 2023.

- ↑ Azerbaycan // MEB Islam Ansiklopedisi. — 1979. — Т. 2, вып. 5. — С. 103–105.

- ↑ И. И. Пантюхов. Антропологические типы Кавказа//ВЕЛЕСОВА СЛОБОДА

- ↑ Yarshater, E (18 August 2011). "The Iranian Language of Azerbaijan". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ↑ Togan 1981, p. 225-227.

- ↑ C. E. Bosworth. Azerbaijan — Islamic history to 1941. Iranica.

- ↑ Togan 1981, p. 256.

- ↑ Köprülü 2000, p. 23.

- ↑ Togan 1981, p. 255.

- ↑ Togan 1981, p. 253.

- ↑ Sümer 1957, p. 441.

- 1 2 Togan 1981, p. 254.

- 1 2 3 4 Hüseynov 2023, pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Заселение Азербайджана тюрками. Сборник "Этническая ономастика". Академия наук СССР. Институт этнографии имени Н.Миклухо-Маклая. Издательство "Наука", М., 1984 г. Archived 2009-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ R. Khanam. Encyclopaedic ethnography of Middle-East and Central Asia: J-O, том 2. Стр. 126–127

- ↑ Məhəmmədhəsən bəy Vəlili-Baharlı ― ""Azərbaycan" (Fiziki-coğrafi, etnoqrafik və iqtisadi oçerk)" Bakı. 1993. Padarlar.

- ↑ Petrushevsky 1949, p. 48.

- ↑ Я.В.Рагозина. Из истории возвышения династии Каджаров // Вестник Санкт-Петербургского Университета. — Санкт-Петербург, 2008. — Т. 9, вып. 2, № 2. — С. 287–294.

- ↑ J. J. Reid, "The Qajar Uymaq in the Safavid Period, 1500–1722", p. 123–124

- ↑ N. Kondo, "How to Found a New Dynasty: The Early Qajars' Quest for Legitimacy", p. 278–279

- ↑ Д.Е.Еремеев. К семантике тюркской этнонимии. Сборник "Этнонимы". Москва: Мысль (1970).

- ↑ L. M. Helfgott, "The Rise of the Qajar Dynasty", p. 130–131

- ↑ Hüseynov 2023, p. 71.

- ↑ Hüseynov, Gurban. Gelecek Dergisi. (2022). Demographic Structure of Azerbaijan During The Ilkhanid Period. 6. 34–44.

- ↑ Sümer 1957, pp. 435–436.

- ↑ Академик В.В.Бартольд. Сочинения / Ответственный редактор тома А.М.Беленицкий. — М.: Наука, 1965. — Т. III. — С. 335. — 712 с.

- ↑ Босуорт К. Э. THE ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF ISLAM. — 1997. — Т. IV. — С. 573.

- ↑ Mustafayev 2013, p. 335.

- ↑ Mustafayev 2013, p. 344.

- ↑ Elisabetta Ragagnin. 28 Dec 2021, Azeri from: The Turkic Languages Routledge. Accessed on: 04 Nov 2023 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781003243809-17 Archived 2023-11-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Ilaha Mahammad gizi Gurbanova. Azərbaycan dili dialekt və şivələrinin etnolinqvistik təhlili. Baku, "Bilik", 2014, p. 240. (in Azerbaijani)

- ↑ Caferoğlu 1954, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Beydili 2003, p. 488.

- ↑ Moradi, A. A rock-cut tomb of the Mongol period in the Ilkhanid capital of Maraghe Archived 2023-11-01 at the Wayback Machine. asian archaeol 6, 15–35 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41826-022-00049-x

- ↑ Boratav 2014, p. 77.

- ↑ Boratav 2014, p. 39.

- ↑ Beydili 2003, p. 486.

- ↑ Beydili 2003, p. 537.

- ↑ Челеби Э. (1983). "Описание крепости Шеки/О жизни племени ит-тиль". Книга путешествия. (Извлечения из сочинения турецкого путешественника ХVII века). Вып. 3. Земли Закавказья и сопредельных областей Малой Азии и Ирана. Москва: Наука. p. 159. Archived from the original on 2023-04-18. Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- 1 2 H. Javadi and K. Burrill (December 15, 1988). "AZERBAIJAN x. Azeri Turkish Literature". iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 2013-02-01. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- ↑ Баку, губернский город Archived 2022-03-25 at the Wayback Machine // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона : в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890–1907.

- ↑ Köprülü 2000, p. 27.

- 1 2 Köprülü 2000, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Atıcı, Ayşe (2021). "Sultan Ahmed Celâyir, Türkçe'ye Verdiği Önem ve Kimlik Üzerine". Disiplinler Arası Dil ve Edebiyat Çalışmaları. Aybil yayınları. 2: 2–9.

- ↑ Togan 1981, p. 260.

- ↑ Prazniak 2014, p. 676.

- ↑ Prazniak 2014, p. 659.

- ↑ Yakupoğlu 2018, pp. 188–189.

- ↑ Prazniak 2014, p. 664.

- ↑ Togan 1981, pp. 267–268.

- ↑ Köprülü, F. (2004). İSLÂM SÛFÎ TARÎKATLERİNE TÜRK-MOĞOL ŞAMANLIĞININ TE'SİRİ . Marife Dini Araştırmalar Dergisi , 4 (1) , 267–275 . Retrieved from http://marife.org/tr/pub/issue/37809/436582 Archived 2023-06-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Togan 1981, p. 284.

- ↑ Haykıran, K. R. "İlhanlı Hâkimiyeti ve İmâmiye Şiîlerî". Milel ve Nihal 17 (2020): 87–109

- ↑ Togan 1981, p. 278.

- ↑ Togan 1981, pp. 279–280.

- ↑ Togan 1981, pp. 285–286.

- ↑ Togan 1981, p. 279.

- ↑ István Vásáry. The role and function of Mongolian and Turkic in Ilkhanid Iran // Turcologia.

- ↑ Prazniak 2014, p. 660.

- ↑ Petrushevsky 1949, p. 36.

- ↑ Шеки (историч. область в Азербайджане) — статья из Большой советской энциклопедии.

'Как независимое государственное образование упоминалось с конца 14 в. Владетелем Ш. был Сиди Ахмед Орлат (из тюркизированного монгольского племени орлатов)'

- ↑ Советская историческая энциклопедия, статья: Под ред. Е. М. Жукова. Шеки // Советская историческая энциклопедия. — М.: Советская энциклопедия. — 1973–1982

В послемонг. время Ш. как независимое государственное образование упоминается с кон. 14 в. Владетелем Ш. был Сиди Ахмед Орлат (из тюркизированного монг. племени орлатов).

- ↑ Petrushevsky 1949, p. 184.

- 1 2 3 4 Ahmet Caferoğlu. Türk Tarihinde Nöker ve Nöker-zadeler Müessesesi, IV. Türk Tarih Kongresi Ankara 10–14 Kasım 1948, Kongreye Sunulan Tebliğler, TDK Yay., Ankara 1952: 251.

- ↑ Starostin, Sergei; Dybo, Anna; Mudrak, Oleg (2003), "*nökör-", in Etymological dictionary of the Altaic languages (Handbuch der Orientalistik; VIII.8), Leiden, New York, Köln: E.J. Brill

- 1 2 Günal Zerrin: İslam Ansiklipedisi – Nöker İstanbul 2007

- ↑ Нагдалиев, Фархад (2006). Ханы Нахичеванские в Российской Империи (PDF). Moscow: Новый Аргумен. p. 432. ISBN 5-903224-01-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-07-05.

- ↑ Law, Henry D. G. (1984) "Modern Persian Prose (1920s-1940s)" Ricks, Thomas M. Critical perspectives on modern Persian literature Washington, D. C.: Three Continents Press s. 132 ISBN 0-914478-95-8, 9780914478959 "cited in Babak, Vladimir; Vaisman, Demian; Wasserman, Aryeh. "Political Organization in Central Asia and Azerbaijan":

- ↑ Б. П. Балаян, "К вопросу об общности этногенеза шахсевен и кашкайцев"

- ↑ Buell, Paul; Anderson, E.N.; de Pablo Moya, Montserrat; Oskenbay, Moldir (2020). Crossroads of Cuisine: The Eurasian Heartland, the Silk Roads and Food. Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004432109. hdl:20.500.12657/51058. ISBN 978-90-04-43210-9. page 250–251.

- ↑ Serdar Oktay and Saide Sadıkoğlu, Gastronomic Cultural Impacts of Russian, Azerbaijani and Iranian Cuisines, International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgfs.2018.03.003 Archived 2023-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Yurttaş, H. & Gökler, B. M. (2022). NAHÇIVAN KARABAĞLAR TÜRBESİ VE ANADOLU'YA YANSIMASI . Sanat ve İkonografi Dergisi , 0 (2) , 28–34 . Retrieved from https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/sidd/issue/69990/1120722 Archived 2023-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ ""Популярная художественная энциклопедия." Под ред. Полевого В. М.; М.: Издательство "Советская энциклопедия", 1986". Archived from the original on 2010-12-08. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi İslam Minyatürleri

78. At ve sahibi H. 2160 nolu albümden, y. 366, 21,5 x 24,5 cm. Resim 30 Atının kuyruğunu düğünlemeğe hazırlanan bir savaşçı tasviridir. Peyzaj, yapraklı bir ağacın dalları ve çiçek kümeleriyle belirlenmiştir. Bu resmin desen halindeki kopyası «Abdal – Bakî al – Bâkûî » imzalıdır (Aslanapa, «Turkische Miniaturmalerei, Abb* 13») Eser, geç Yüan ve erken Ming devrinden Çin de çok popüler olan bir konunun İslam i kopyasıdır, XV. Yüzyıl.

— Aslanapa, pl. 6, Abb. 12; Loehr, p, 87; İpşiroğlu, MM, fig. 47; Ipşiroğlu, 70.

Sources

- Togan, Zeki Velidi (1981). Ümumi türk tarihine giriş (cilt I). Enderun Kitabevi.

- Mustafayev, Shahin (2013). "Ethnolinguistic Processes in the Turkic Milieu of Anatolia and Azerbaijan (14th–15th Centuries)". In Lascu, Stoica; Fetisleam, Melek (eds.). Contemporary Research in Turkology and Eurasian Studies: A Festschrift in Honor of Professor Tasin Gemil on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday. Cluj-Napoca: Cluj University Press. pp. 333–346. ISBN 978-973-595-622-6. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- Sümer, Faruk (1957). "Azerbaycan'ın Türkleşmesi Tarihine Umumi Bir Bakı". Belleten (in Turkish). 21 (83): 429–448. ISSN 0041-4255. Archived from the original on 2023-10-26.

- Durand-Guédy, David (2010). Mongols, Turks and Others: Eurasian Nomads and the Sedentary World by Reuven Amitai, Michal Biran. Iranian Studies. ISBN 978-9-0041-4096-7.

- Köprülü, Mehmet Fuat (2000). Azeri. Baku: Elm.

- Hüseynov, Gurban (2023). "Moğolların Azerbaycan Saldırıları ve İlhanlılar Dönemi Azerbaycan'da Moğol Yerleşim Yerleri". Turkology Research (53): 63–79. ISSN 0041-4255.

- Caferoğlu, Ahmet (1954). "Azerbaycan ve Anadolu Ağızlarındaki Moğolca Unsurlar". Türk Dili Araştırmalar Yıllığı. Belleten. 2: 1–10. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30.

- Beydili, Celal (2003). Türk Mitolojisi Ansiklopedik Sözlük (PDF). Yurt Yayınevi. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-11-29.

- Boratav, Pertev Naili (2014). Nasreddin Hoca. Istanbul: Islık Yayınları. ISBN 978-605-64699-0-9.

- Prazniak, Roxann (2014). "Ilkhanid Buddhism: Traces of a Passage in Eurasian History". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 56 (3): 650–680. doi:10.1017/S0010417514000280. S2CID 145590332.

- Yakupoğlu, Cevdet (2018-03-18). "Azerbaycan´ın Hôy Yöresinde Türk Egemenliği (XI- XVI. Yüzyıllar)". History Studies International Journal of History. 10 (2): 175–193. doi:10.9737/hist.2018.590.

- Petrushevsky, Ilya Pavlovich (1949). Очерки по истории феодальных отношений в Азербайджане и Армении в XVI — начале XIX вв (in Russian).

Further reading

- Abdullayev, E. Z. (1987). AZERBAYCAN-MOĞOL DİL İLİŞKİLERİ . Türk Dili Araştırmaları Yıllığı — Belleten, 35 (1987), 1–9 . Retrieved from AZERBAYCAN-MOĞOL DİL İLİŞKİLERİ Archived 2023-06-17 at the Wayback Machine

- "Azeri şivesinde nohur ve lap kelimeleri", Rocznik Orientalistyczny, XVII, Krakow, 1953, (s. 180–183)

- Caferoğlu, Ahmet: "Azerî Lehçesinde Bazı Mogol unsurları", Azerbaycan Yurt Bilgisi, sayı 6–7, İstanbul, 1932 (I, s. 215–226); sayı 25, İstanbul, 1934, (II, s. 3–8) (13 kelime)

- Lindsay, R. (2010). Mutual Intelligibility Among Turkic Languages. Retrieved December 18, 2015, from Academia: Mutual Intelligibility Among the Turkic Languages Archived 2023-11-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Ghorbannejad, Parisa. (2008). Influence and Expansion Ibn Arabi's School among Sufis of Azerbaijan Mongol Era Archived 2023-11-01 at the Wayback Machine. 4. 71–97.

- Ghorbannejad, Parisa. (2009). Sufism in Azerbaijan during the Mongol period Archived 2023-11-01 at the Wayback Machine تصوف در آذربایجان عهد مغول.