Banca Romana scandal trial | |

| Date | 1893–1894 |

|---|---|

| Location | Italy |

| Participants | The Banca Romana had loaned large sums to property developers but was left with huge liabilities when the real estate bubble collapsed in 1887. |

| Outcome | The scandal prompted a new banking law, tarnished the prestige of the Prime Ministers Francesco Crispi and Giovanni Giolitti and prompted the collapse of the latter's government in November 1893. |

The Banca Romana scandal surfaced in January 1893 in Italy over the bankruptcy of the Banca Romana,[1] one of the six national banks authorised at the time to issue currency. The scandal was the first of many Italian corruption scandals, and discredited both ministers and parliamentarians, in particular those of the Historical Left and was comparable to the Panama Canal Scandal that was shaking France at the time, threatening the constitutional order.[2] The crisis prompted a new banking law, tarnished the prestige of the Prime Ministers Francesco Crispi and Giovanni Giolitti and prompted the collapse of the latter's government in November 1893. The scandal led also to the creation of one central bank, the Bank of Italy.

Background

The Banca Romana was founded by French and Belgian investors in 1833 under the jurisdiction of Pope Gregory XVI.[3] (Other sources mention 1835)[4] After the fall of the short-lived Roman Republic in 1849, the bank was renamed Banca dello Stato Pontificio in 1850, and became the official bank of the Papal States, acquiring a monopoly of currency issue, deposit collection, and credit in the Papal States.[3] Following the annexation of the Papal States to Italy in 1870, the bank retook its former name of Banca Romana.[3] At the time, Italy had no central bank and in 1874 the Banca Romana was made one of the six banks authorised by the Italian government to issue currency.[4]

Due to rising inflation and easy credit,[5] the Banca Romana and the five other issue banks (banks that were allowed to issue banknotes), had steadily increased their note circulation. In 1887 five of the issue banks had exceeded their legal limit, a fact well known to the government and banking and financial circles.[5] However, restricting credit during a speculative construction boom was considered politically impossible.[5] Since the late 1880s, the Italian economy had been sliding into a deep recession. New tariffs had been introduced in 1887 on agricultural and industrial goods and a trade war with France followed, which badly damaged Italian commerce. Many farmers, especially in southern Italy, suffered severely, which eventually led to the uprising of the Fasci Siciliani.[6] Additionally the collapse of a speculative boom based on a substantial urban rebuilding programme gravely damaged Italian banks.[7]

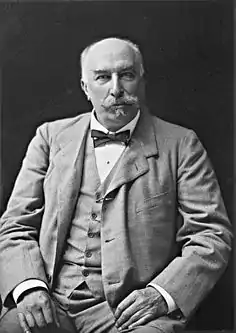

Under the direction of Ludovico Guerrini (1870–81) the bank had been managed prudently and its banknote circulation had remained within the legal limits. However, his successor as governor of the Banca Romana, Bernardo Tanlongo, was a peculiar man, semi-literate but with a genius for accounts and finance.[8] "He was not a womanizer, he never played, he is the antithesis of all elegance, his frugality resembles avarice," was how the Corriere della Sera once described him.[9] A former farm hand and former spy during the Roman Republic in 1849, he made his career in the bank in the Papal State, providing illicit entertainment to Vatican officials. Tanlongo remained at his post in the Banca Romana after the Italian unification and was promoted governor in 1881.[8] Over the years, Tanlongo had built an influential network through strong personal connections with Roman aristocrats and businessmen, freemasons and Jesuit clerics, top government officials and industrialists, including the Royal Family. He was their agent in real estate speculations, and subsequently started to speculate on his own account.[3] He had a remarkable ability to secure friendships and protection by providing loans to cover up secrets.[8]

Government inspection

In 1889, three Turin banks heavily involved in financing speculative building in Rome suspended payments. The note-issuing banks were persuaded by the government to bail out other banks in order to avoid a major disaster.[5][10] They were allowed to issue bank notes in excess of their reserves and legal limits in an attempt to steer clear of economic recession. However, this caused them to become entangled in the crisis.[10]

In June 1889 inspections of the Banca Romana by a government commission revealed serious irregularities in its administration and accounts and that 91 percent of the assets of the bank were illiquid. Moreover, the bank's directors had committed a criminal offence by permitting an additional number of banknotes with duplicate numbering to be printed.[11] The Banca Romana had loaned large sums to property developers but was left with huge liabilities when the real estate bubble collapsed in 1887.[12] One of the government reports concluded:

At the Banca Romana the accounting system is defective, the creation of bank notes is abnormal, their issuing is excessive and partly camouflaged, the arrangement of the general reserve fund is confused, the store of notes for circulation and withdrawal is inadequately protected, and further illegitimate and illegal issues must be expected.[10]

Prime Minister Francesco Crispi and his Treasury Minister Giovanni Giolitti knew of the 1889 government inspection report, but feared that exposure might undermine public confidence and suppressed the report.[5] In addition, they also wanted to avoid it becoming known that the Banca Romana, like other banks, had extended substantial loans to politicians (including themselves), often without interest. This was a common way for politicians to finance election expenses in return for favours.[10]

An additional problem was that Banca Romana was a private company with private shareholders but with a public role as an issuing bank, and therefore constantly had an opposing interest between its public role as an issuing bank and its private interest to maximise profits as much as possible.[11] The need for a single bank in charge of issuing banknotes and at the same time a reduction in the circulation of notes, was part of much debate in the following years. Both Crispi and his successors, Antonio Di Rudinì and Luigi Luzzatti, preferred to rely on time rather than daring to face the revelations of fraud and the political mayhem that any serious attempt to reform the banking system would inevitably trigger. That proved to be a tragic mistake.[5]

The scandal erupts

Giolitti, who was prime minister from May 1892 to November 1893, tried to get the governor of Banca Romana, Tanlongo, appointed as senator, which would have given him immunity from prosecution.[6] Before Giolitti could appoint the former bank governor, the report was leaked to deputies Napoleone Colajanni and Lodovico Gavazzi who divulged its contents to the Parliament at the end of 1892.[13] On 20 December 1892 Colajanni read out long extracts in Parliament and Giolitti was forced to appoint an expert commission to investigate the note-issuing banks.[5] The close friendship of Giolitti's Treasury Minister, Bernardino Grimaldi, with Tanlongo and the introduction of a bill – endorsed by Giolitti and then withdrawn – giving the existing banks the right to issue currency for another six years, increased suspicions of wrongdoing.[13]

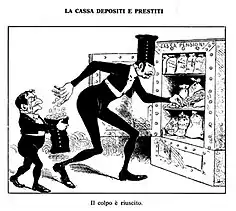

The expert commission report, published on 18 January 1893, confirmed the serious state of affairs in the Banca Romana: a deficiency of cash, cooked accounts, a note circulation of 135 million lire instead of the 75 million lire permitted by law, a great quantity of bad debts due to speculation in building, and 40 million lire in a duplicated series of notes that had been printed in Britain but not issued owing to the honesty of minor officials of the bank.[5] Politicians had received money to finance their election expenses and to run or bribe newspapers. The next day, Tanlongo, the bank's director Cesare Lazzaroni, and several subordinates were arrested,[14] but they were acquitted by the Court on 15 July 1894.[8][15] Tanlongo accused Giolitti of receiving money through the Director General of the Treasury Carlo Cantoni, Agriculture Minister Pietro Lacava, and Grimaldi.[16]

New banking law and Giolitti's fall

The scandal prompted a new investigation and accelerated the process of passing a new banking law to address the liquidity of Italian banks.[12] Giolitti was well equipped to deal with the technical side of the problem and, although late, he acted energetically. Within a few months, a new Banking Act was introduced in August 1893 that liquidated the Banca Romana and reformed the entire system for issuing banknotes. Only the recently established Banca d'Italia – also in charge of liquidating the Banca Romana –, and two southern banks (the Banco di Napoli and the Banco di Sicilia) were now given the concession to issue banknotes, which was put under tighter state control.[5][11][17]

The main purpose of the reform, however, was to rapidly solve the financial problems of the Banca Romana, as well as to cover up a scandal that involved many politicians, rather than to design a new national banking system. Regional interests were still strong; hence the compromise that permitted three note issuing banks. The reform neither immediately restored confidence nor achieved establishment of a single note issuing bank, as envisaged by Finance Minister Sidney Sonnino, but it was nevertheless a sound reform, strengthening the leading role of the newly formed Banca d'Italia which was seen as a decisive step towards the unification of note issuance and the control of money supply in Italy.[5][12]

Politically, however, Giolitti did not survive the scandal. He had been Finance Minister in the government that had suppressed the original 1889 report. As Prime Minister he had borrowed from the Banca Romana for governmental purposes in August 1892, had nominated the bank's governor, Tanlongo, to the Senate, and had resisted a parliamentary enquiry, encouraging suspicions that he had something to hide.[5] Tanlongo and the Banca Romana's tried to defame Giolitti, calculating that a change of government would result in the release of the defendants.[5]

On 23 November 1893, at the opening of the Italian Parliament, the Italian Chamber of Deputies insisted that the sealed report of the Commission that investigated the bank scandals be read immediately. The conclusions of the Commission, that former Prime Minister Crispi, Prime Minister Giolitti, and former Finance Minister Luigi Luzzatti had been aware of the condition of the Banca Romana but had held back that information, were hailed amidst disorder with shouts for the resignation of Giolitti. Rival deputies exchanged insults and pushed and pulled each other over seats and desks over a disputed effort to impeach the government. While the President of the Chamber, Giuseppe Zanardelli, and the minister left the session, deputies refused orders to leave until the light was turned off at 10 PM. Opposition deputies were cheered by a large crowd that had assembled on the street. Colajanni incited the multitude, shouting: "You are faint hearted! You have no convictions. If you had, you would put the torch to this parliamentary hovel!"[18]

Many politicians were implicated but Giolitti was targeted in particular: "He knew of the bank's irregularities as early as 1889," the report said, "although as late as last February he declared that he did not know of them." The Commission concluded that pressing charges that Giolitti had used the bank's money in the last election campaign could not be proved although it declined to affirm that it was disproved.[18] Giolitti had to resign on 24 November 1893.[19]

Giolitti's counter attack

Increasing the crisis, the Giolitti and the Crispi-Tanlongo camp leaked documents to the detriment of both politicians.[16] The trial against Tanlongo and other directors of the bank for embezzlement and other fraudulent practices began on 2 May 1894.[20] Testimony at the trial revealed that Giolitti had been aware of the condition of the Banca Romana in 1889, but had held back that information. Giolitti also allegedly received money from the bank for election purposes.[21] Emotions at the trial sometimes ran high; once leading to an adjournment due to a fierce fist-fight between former Minister Luigi Miceli and a Bank Inspector, who testified against Miceli.[22] The acquittal of Bernardo Tanlongo and the other Banca Romana defendants in July 1894[15] freed Giolitti's successor as Prime Minister, Francesco Crispi, to engage in open warfare against Giolitti. Tanlongo and his co-defendants were acquitted on the grounds that the "major criminals are elsewhere" – an obvious reference to Giolitti (and a striking contrast to the sentences passed on the leaders of the Fasci Siciliani). In September 1894 Crispi subsequently ordered the prosecution of police officials for abstracting documents from Tanlongo's house that allegedly incriminated Giolitti.[23]

Giolitti now had an opportunity to counter-attack, releasing a package of documents compromising Crispi with evidence that he had concealed from the parliamentary inquiry financial transactions and debts contracted by Crispi, his family and friends with the Banca Romana. On 11 December 1894 the package – known as the "Giolitti envelope" – was handed to the President of the Chamber of Deputies. A committee of five was appointed to examine the new evidence, including Felice Cavallotti, one of Crispi's main allies. However, confronted with the new facts he realised that Giolitti had been misjudged.[23] Notes of the Banca Romana cashier implicated Prime Minister Crispi (with several drafts and a note for 1,050,000 lire), as well as the former president of the Chamber, Giuseppe Zanardelli, Giolitti's former Treasury Minister, Bernardino Grimaldi and other ex-Ministers. Some journalists received 200,000 lire and others 75,000 lire for press and election services. Letters from Bernardo Tanlongo explained that the deficit of the bank was due to disbursements to Ministers, Senators and members of the press.[24]

Aftermath

After the publication of the committee's report on 15 December 1894,[24] Crispi dissolved the Chamber by decree amidst increasing protests, which compelled Giolitti – now that his parliamentary immunity was lifted – to leave the country; officially to visit his daughter in Berlin.[25] Crispi denounced the Giolitti documents as a mass of lies, but rumours of Crispi's resignation turned out to be unfounded. Five battalions of infantry had been brought to Rome to quell possible riots.[26] Giolitti was accused of embezzlement as well as libel against Crispi and his wife, and was summoned before the courts in February 1895 after the Public Prosecutor, sustained by lower courts, had started the prosecution. However, on 24 April 1895 the Supreme Court decided that Giolitti could not be tried by an ordinary civil court, as Giolitti had argued, because he had made his accusations against Crispi in the Chamber. Only the Senate could hear the case.[25][27][28]

Despite Crispi's resounding victory at the general elections in May 1895, the scandal would backfire against him.[23] On 24 July the Government decided to present Giolitti's evidence about the role of Crispi in the scandal and other matters to the Chamber of Deputies and to have a special commission examine them.[29] In June 1895, the French newspaper Le Figaro published documents compromising Crispi, showing evidence that he had concealed financial transactions and debts contracted by Crispi, his family and friends with the Banca Romana, from the 1893 parliamentary inquiry .[30] Giolitti regained much of his prestige after the political debate in December 1895 when the Chamber declined to indict Giolitti, who had asked to be brought for the Senate.[31][32] The scandal was now hurriedly buried after nearly three years. Most of the shortcomings had been political negligence rather than criminal but the uproar about bribes and cover-ups had discredited political and banking institutions and the reputation of politicians. The prestige of both Crispi and Giolitti was tarnished substantially, favouring the so-called Extreme Left headed by Cavallotti.[4][10][23]

In popular culture

In 1977 the Italian state television channel Rete Due (now Rai 2) broadcast a mini series on the scandal in three parts. On 17–18 January 2010, Rai Uno broadcast a two-part mini series directed by Stefano Reali.[33]

References

- ↑ Italy Has Her Scandal; Ex-Premier Crispi Said To Be Involved, The New York Times, January 27, 1893

- ↑ Italy's Financial Scandals; Kingdom startled by the peril of the national finances, The New York Tribune, 12 February 1893

- 1 2 3 4 Pani, Crisis and Reform: The 1893 Demise of Banca Romana

- 1 2 3 Sarti, Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present, pp. 135–36

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Seton-Watson, Italy from liberalism to fascism, pp. 154–56

- 1 2 Duggan, The Force of Destiny, p. 340

- ↑ Davis, John A., Socialism and the Working Classes in Italy Before 1914 , in Geary, Dick (ed.) (1989), Labour and Socialist Movements in Europe Before 1914, Berg, ISBN 0-85496-200-X, p. 188

- 1 2 3 4 (in Italian) Tanlongo, il maestro di Calvi e Sindona, Corriere della Sera, April 26, 1993

- ↑ (in Italian) L' abominevole Tanlongo e il crac della Banca Romana, Corriere della Sera, February 8, 2004

- 1 2 3 4 5 Clark, Modern Italy, pp. 119–22

- 1 2 3 Pohl & Freitag, Handbook on the history of European banks, p. 564

- 1 2 3 Alfredo Gigliobianco and Claire Giordano, Economic Theory and Banking Regulation: The Italian Case (1861–1930s), Quaderni di Storia Economica (Economic History Working Papers), Nr. 5, November 2010

- 1 2 De Grand, The Hunchback's Tailor, pp. 42–44

- ↑ Governor and Cashier Arrested; Large Overissue of Notes by The Banca Romana, The New York Times, January 20, 1893

- 1 2 Tanlongo Not Guilty; Jury Acquits Him of Fraud in Managing the Banca Romana, The New York Times, July 29, 1894

- 1 2 De Grand, The Hunchback's Tailor, p. 46

- ↑ (in Italian) Legge n. 449 del 10 agosto 1893 Archived 2013-09-19 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 The Italian Bank Scandal; Report of the Investigation Read To Parliament. Many Deputies and Other Public Men Implicated, The New York Times, November 24, 1893

- ↑ Cabinet Forced To Resign; Italian Ministers Called "Thieves" by the People, The New York Times, November 25, 1893

- ↑ The Banca Romana Trials Begun, The New York Times, May 3, 1894

- ↑ They Accuse Giolotti, The New York Times, May 18, 1894

- ↑ Adjournment In An Uproar; Almost A Riot At The Trial Of An Italian Banker, The New York Times, May 20, 1894

- 1 2 3 4 Seton-Watson, Italy from liberalism to fascism, pp. 172–74

- 1 2 Accusing Signor Crispi; The Banca Romana Chest of Documents a Pandora's Box, The New York Times, December 16, 1894

- 1 2 De Grand, The Hunchback's Tailor, p. 63

- ↑ Soldiers To Guard Rome; Troops Ordered to the City in Anticipation of Riots, The New York Times, December 17, 1894

- ↑ Crispi's Tormentor Sustained; Ex-Premier Giolitti May Not Be Tried by a Civil Tribunal, The New York Times, April 25, 1895

- ↑ Editorial, The New York Times, May 18, 1895

- ↑ Giolitti's Charges Against Crispi, The New York Times, July 25, 1895

- ↑ Accusations Against Crispi; Details of the Portentous Charges Made by Giolitti, The New York Times, June 9, 1895

- ↑ Giolitti Escapes Trial; Attempt to Prosecute Him for Theft Fails in the Chamber, The New York Times, December 14, 1895

- ↑ De Grand, The Hunchback's Tailor, p. 64

- ↑ Lo scandalo della Banca Romana Archived 2010-12-02 at the Wayback Machine, Albatross Entertainment (accessed January 15, 2012)

Sources

- Clark, Martin (1984/2014). Modern Italy, 1871 to the Present, New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-4058-2352-4

- De Grand, Alexander J. (2001). The hunchback's tailor: Giovanni Giolitti and liberal Italy from the challenge of mass politics to the rise of fascism, 1882–1922, Wesport/London: Praeger, ISBN 0-275-96874-X (online edition Archived 2008-02-05 at the Wayback Machine)

- Duggan, Christopher (2008). The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 0-618-35367-4

- Pani, Marco (2017). Crisis and Reform: The 1893 Demise of Banca Romana, IMF Working Paper (WP/17/274), December 2017.

- Pohl, Manfred & Sabine Freitag (European Association for Banking History) (1994). Handbook on the history of European banks, Aldershot: Edward Elgar Publishing, ISBN 1-85278-919-0

- Sarti, Roland (2004). Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present, New York: Facts on File Inc., ISBN 0-8160-7474-7

- Seton-Watson, Christopher (1967). Italy from liberalism to fascism, 1870–1925. London: Methuen & Co Ltd. ISBN 0-416-18940-7.

External links

- (in Italian) Commissione d'inchiesta sulle banche, Archivio storico della Camera dei deputati