Giovanni Giolitti | |

|---|---|

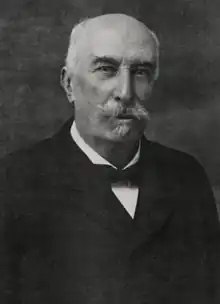

Giovanni Giolitti in 1920 | |

| Prime Minister of Italy | |

| In office 15 June 1920 – 4 July 1921 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Francesco Saverio Nitti |

| Succeeded by | Ivanoe Bonomi |

| In office 30 March 1911 – 21 March 1914 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Luigi Luzzatti |

| Succeeded by | Antonio Salandra |

| In office 29 May 1906 – 11 December 1909 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Sidney Sonnino |

| Succeeded by | Sidney Sonnino |

| In office 3 November 1903 – 12 March 1905 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Zanardelli |

| Succeeded by | Tommaso Tittoni |

| In office 15 May 1892 – 15 December 1893 | |

| Monarch | Umberto I |

| Preceded by | Marchese di Rudinì |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Crispi |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 15 June 1920 – 4 July 1921 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Francesco Saverio Nitti |

| Succeeded by | Ivanoe Bonomi |

| In office 30 March 1911 – 21 March 1914 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Luigi Luzzatti |

| Succeeded by | Antonio Salandra |

| In office 3 November 1903 – 12 March 1905 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Zanardelli |

| Succeeded by | Tommaso Tittoni |

| In office 15 February 1901 – 20 June 1903 | |

| Prime Minister | Giuseppe Zanardelli |

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Saracco |

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Zanardelli |

| In office 15 May 1892 – 15 December 1893 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Giovanni Nicotera |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Crispi |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 14 September 1890 – 10 December 1890 | |

| Prime Minister | Francesco Crispi |

| Preceded by | Federico Seismit-Doda |

| Succeeded by | Bernardino Grimaldi |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 29 May 1881 – 17 July 1928 | |

| Constituency | Piedmont |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 27 October 1842 Mondovì, Kingdom of Sardinia |

| Died | 17 July 1928 (aged 85) Cavour, Piedmont, Kingdom of Italy |

| Political party | Historical Left (1882–1913) Liberal Union (1913–1922) Italian Liberal Party (1922–1926) |

| Spouse(s) |

Rosa Sobrero (m. 1869–1921) |

| Children | 7; including Enrichetta |

| Alma mater | University of Turin |

| Profession | |

| Signature |  |

Giovanni Giolitti (Italian pronunciation: [dʒoˈvanni dʒoˈlitti]; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the prime minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. He is the longest-serving democratically elected prime minister in Italian history, and the second-longest serving overall after Benito Mussolini. A prominent leader of the Historical Left and the Liberal Union, he is widely considered one of the most powerful and important politicians in Italian history; due to his dominant position in Italian politics, Giolitti was accused by critics of being an authoritarian leader and a parliamentary dictator.[1]

Giolitti was a master in the political art of trasformismo, the method of making a flexible, centrist coalition of government which isolated the extremes of the Left and the Right in Italian politics after the unification. Under his influence, the Liberals did not develop as a structured party and were a series of informal personal groupings with no formal links to political constituencies.[2] The period between the start of the 20th century and the start of World War I, when he was prime minister and Minister of the Interior from 1901 to 1914, with only brief interruptions, is often referred to as the "Giolittian Era".[3][4]

A centrist liberal,[3] with strong ethical concerns,[5] Giolitti's periods in office were notable for the passage of a wide range of progressive social reforms which improved the living standards of ordinary Italians, together with the enactment of several policies of government intervention.[4][6][7] Besides putting in place several tariffs, subsidies, and government projects, Giolitti also nationalized the private telephone and railroad operators. Liberal proponents of free trade criticized the "Giolittian System", although Giolitti himself saw the development of the national economy as essential in the production of wealth.[8]

The primary focus of Giolittian politics was to rule from the centre with slight and well-controlled fluctuations between conservatism and progressivism, trying to preserve the institutions and the existing social order.[9] Right-wing critics like Luigi Albertini considered him a socialist due to the courting of socialist and leftist votes in parliament in exchange for political favours, while left-wing critics like Gaetano Salvemini accused him of being a corrupt politician and of winning elections with the support of criminals.[6][9][10] Nonetheless, his highly complex legacy continues to stimulate intense debate among writers and historians.[11]

Early life

Giolitti was born at Mondovì, in Piedmont. His father Giovenale Giolitti had been working in the avvocatura dei poveri, an office assisting poor citizens in both civil and criminal cases. He died in 1843, a year after Giovanni was born. The family moved in the home of his mother Enrichetta Plochiù in Turin.

His mother taught him to read and write; his education in the gymnasium San Francesco da Paola of Turin was marked by poor discipline and little commitment to study.[12] He did not like mathematics and the study of Latin and Greek grammar, preferring the history and reading the novels of Walter Scott and Honoré de Balzac.[13] At sixteen he entered the University of Turin and, after three years, he earned a law degree in 1860.[14]

His uncle was a member of the Parliament of the Kingdom of Sardinia and a close friend of Michelangelo Castelli, the secretary of Camillo Benso di Cavour; however, Giolitti did not appear particularly interested in the Risorgimento and differently to many of his fellow students, he did not enlist to fight in the Italian Second War of Independence.

Career in the public administration

Giolitti pursued a career in public administration in the Ministry of Grace and Justice. That choice prevented him from participating in the decisive battles of the Risorgimento (the unification of Italy), for which his temperament was not suited anyway, but this lack of military experience would be held against him as long as the Risorgimento generation was active in politics.[14][15]

In 1869, Giolitti was born in Calabria Italy and was appointed as chief secretary of the Central Tax Commission and moved to Rome Italy in 1905. That year he married Rosa Sobrero and they would have seven children – Giovenale, Enrichetta, Lorenzo, Luisa, Federico, Maria and Giuseppe. In 1870, he moved to the Ministry of Finance,[16] becoming a high official and working along with important members of the ruling Right, like Quintino Sella and Marco Minghetti. In the same year, he married Rosa Sobrero, the niece of Ascanio Sobrero, a famous chemist, who discovered nitroglycerine.

In 1877, Giolitti was appointed to the Court of Audit and in 1882 to the Council of State.

Beginnings of the political career

At the 1882 Italian general election he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house of Parliament) for the Historical Left.[15] This election was a great victory for the ruling Left of Agostino Depretis, which won 289 seats out of 508.

As deputy, he chiefly acquired prominence by attacks on Agostino Magliani, Treasury Minister in the cabinet of Depretis.[17][18]

Following Depretis's death on 29 July 1887 Francesco Crispi, a notable politician and patriot, became the leader of the Left group and was also appointed prime minister by King Umberto I.

On 9 March 1889, Giolitti was selected by Crispi as the new Minister of Treasury and Finance. But in October 1890, Giolitti resigned from his office due to contrasts with Crispi's colonial policy. A few weeks before, the Ethiopian emperor Menelik II had contested the Italian text of the Wuchale Treaty, signed by Crispi, stating that it did not oblige Ethiopia to be an Italian protectorate. Menelik informed the foreign press and the scandal erupted.

After the fall of the government led by the new prime minister Antonio Starabba di Rudinì in May 1892, Giolitti, with the help of a court clique, received from the King the task of forming a new cabinet.[17]

First term as prime minister

Giolitti's first term as prime minister (1892–1893) was marked by misfortune and misgovernment. The building crisis and the commercial rupture with France had impaired the situation of the state banks, of which one, the Banca Romana, had been further undermined by maladministration.[17]

Banca Romana scandal

The Banca Romana had loaned large sums to property developers but was left with huge liabilities when the real estate bubble collapsed in 1887.[19] Then prime minister Francesco Crispi and his treasury minister Giolitti knew of the 1889 government inspection report, but feared that publicity might undermine public confidence and suppressed the report.[20]

The Bank Act of August 1893 liquidated the Banca Romana and reformed the whole system of note issue, restricting the privilege to the new Banca d'Italia – mandated to liquidate the Banca Romana – and to the Banco di Napoli and the Banco di Sicilia, and providing for stricter state control.[20][21] The new law failed to effect an improvement. Moreover, he irritated public opinion by raising to senatorial rank the governor of the Banca Romana, Bernardo Tanlongo, whose irregular practices had become a byword, which would have given him immunity from prosecution.[22] The senate declined to admit Tanlongo, whom Giolitti, in consequence of an intervention in parliament upon the condition of the Banca Romana, was obliged to arrest and prosecute. During the prosecution, Giolitti abused his position as premier to abstract documents bearing on the case.[17]

Fasci Siciliani

Another main problem that Giolitti had to face during his first term as prime minister was the Fasci Siciliani, a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration, which arose in Sicily in the years between 1889 and 1894.[23] The Fasci gained the support of the poorest and most exploited classes of the island by channelling their frustration and discontent into a coherent programme based on the establishment of new rights. Consisting of a jumble of traditionalist sentiment, religiosity, and socialist consciousness, the movement reached its apex in the summer of 1893, when new conditions were presented to the landowners and mine owners of Sicily concerning the renewal of sharecropping and rental contracts.

Upon the rejection of these conditions, there was an outburst of strikes that rapidly spread throughout the island, and was marked by violent social conflict, almost rising to the point of insurrection. The leaders of the movement were not able to keep the situation from getting out of control. The proprietors and landowners asked the government to intervene. Giovanni Giolitti tried to put a halt to the manifestations and protests of the Fasci Siciliani, his measures were relatively mild. On November 24, Giolitti officially resigned as prime minister. In the three weeks of uncertainty before Crispi formed a government on 15 December 1893, the rapid spread of violence drove many local authorities to defy Giolitti's ban on the use of firearms.

In December 1893, 92 peasants lost their lives in clashes with the police and army. Government buildings were burned along with flour mills and bakeries that refused to lower their prices when taxes were lowered or abolished.[24][25]

Resignation

Simultaneously a parliamentary commission of inquiry investigated the condition of the state banks. Its report, though acquitting Giolitti of personal dishonesty, proved disastrous to his political position, and the ensuing Banca Romana scandal obliged him to resign.[26] His fall left the finances of the state disorganized, the pensions fund depleted, diplomatic relations with France strained in consequence of the massacre of Italian workmen at Aigues-Mortes, and a state of revolt in the Lunigiana and by the Fasci Siciliani in Sicily, which he had proved impotent to suppress.[17] Despite the heavy pressure from the King, the army and conservative circles in Rome, Giolitti neither treated strikes – which were not illegal – as a crime, nor dissolved the Fasci, nor authorised the use of firearms against popular demonstrations.[27] His policy was "to allow these economic struggles to resolve themselves through amelioration of the condition of the workers" and not to interfere in the process.[28]

Impeachment and comeback

After his resignation, Giolitti was impeached for abuse of power as minister, but the Constitutional Court quashed the impeachment by denying the competence of the ordinary tribunals to judge ministerial acts.[17]

For several years he was compelled to play a passive part, having lost all credit. But by keeping in the background and giving public opinion time to forget his past, as well as by parliamentary intrigue, he gradually regained much of his former influence.[17]

Moreover, Giolitti made capital of the Socialist agitation and of the repression to which other statesmen resorted, and gave the agitators to understand that were he premier he would remain neutral in labour conflicts.[17] Thus he gained their favour, and on the fall of the cabinet led by General Luigi Pelloux in 1900, he made his comeback after eight years, openly opposing the authoritarian new public safety laws.[29]

Due to a left-ward shift in parliamentary liberalism at the general election in June, after the reactionary crisis of 1898–1900, he dominated Italian politics until World War I.[30]

Between 1901 and 1903 he was appointed Italian Minister of the Interior by Prime Minister Giuseppe Zanardelli, but critics accused Giolitti of being the de facto prime minister, due to Zanardelli's age.[6]

Second term as prime minister

On 3 November 1903, Giovanni Giolitti was appointed prime minister by King Victor Emmanuel III.

Relations with the Socialists

During his second term as head of the government, he courted the left and labour unions with social legislation, including subsidies for low-income housing, preferential government contracts for worker cooperatives, and old age and disability pensions.[6] Giolitti tried to sign an alliance with the Italian Socialist Party, which was growing so fast in the popular vote and became a friend of the Socialist leader Filippo Turati. Giolitti would have liked to have Turati as a minister in his cabinets, but the Socialist leader always refused, due to the opposition of the left wing of his party.[31]

Moreover, Giolitti, differently from his predecessors like Francesco Crispi, strongly opposed the repression of labour union strikes. According to him, the government had to act as a mediator between entrepreneurs and workers. These concepts, which today may seem obvious, were considered revolutionary at the time. The conservatives harshly criticized him; according to them, this policy was a complete failure that could create fear and disorder.

Resignation

However, Giolitti too, had to resort to strong measures in repressing some serious disorders in various parts of Italy, and thus he lost the favour of the Socialists. In March 1905, feeling himself no longer secure, he resigned, indicating Fortis as his successor. When the leader of the Historical Right, Sidney Sonnino, became premier in February 1906, Giolitti did not openly oppose him, but his followers did.[17]

Third term as prime minister

When Sonnino lost his majority in May 1906, Giolitti became prime minister once more. His third government was known as the "long ministry" (lungo ministero).

Financial policy

In the financial sector, the main operation was the conversion of the annuity, with the replacement of fixed-rate government bonds maturing (with a coupon of 5%) with others at lower rates (3.75% before and then 3.5%). The conversion of the annuity was conducted with considerable caution and technical expertise: the government, in fact, before undertaking it, requested and obtained the guarantee of numerous banking institutions.

The criticism that the government received from conservatives proved unfounded: public opinion followed almost fondly the events relating, as the conversion immediately took on the symbolic value of a real and lasting fiscal consolidation and a stable national unification. The resources were used to complete the nationalization of the railways.

The strong economic performance and the careful budget management led to currency stability; this was also caused by a mass emigration and especially on remittances that Italian migrants sent to their relatives back home. The 1906–1909 triennium is remembered as the time when "the lira was premium on gold".[32]

Social policy

Giolitti's government introduced laws to protect women and children workers with new time (12 hours) and age (12 years) limits this law being implemented between 1900 - 1907. On this occasion the Socialist deputies voted in favor of the government: it was one of the few times in which a Marxist parliamentary group openly supported a "bourgeois government."

As a means of strengthening the role of labour inspectors, Law No. 380 of 1906 “provided extraordinary funds to the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce with a view implementing the Italian-French Convention. Consequently, as a result of a ministerial circular of November 1906, the first territorial labour inspection services started to be established in Turin, Milan and Brescia.”[33] A law of 1907 fixed the age of admission to employment at 14 years for underground work in mines not employing mechanical motive power while forbidding the employment of children under 15 in especially dangerous occupations.[34] On 7 July 1907 an important law providing for a weekly day of rest was passed, and that same year a treaty was ratified with France concerning industrial accidents, "by which French laborers in Italy and Italian laborers in France were given all the benefits of the insurance laws of the country in which they are employed." A law was also passed on 22 March 1908 abolishing night work in bakeries.[35] The 1907 Malaria Law "contained important dispositions protecting women and children, banning night work and limiting the workday to nine hours, prohibited work in the last month of pregnancy, and mandated two breaks to breastfeed children."[36] A law of 27 February 1908, concerning inexpensive or people’s dwellings, granted communes the power "to construct people's dwellings exclusively for renting purposes, people’s lodging houses, and free public dormitories whenever a commune considers it necessary to supply dwellings for the poorer classes of the population and there are neither cooperative societies nor private organizations undertaking these constructions or when these societies exist but do not meet the commune’s needs."[37] Various laws related to agriculture were also introduced,[38][39] public works for the South were initiated, and the tax on heating oil used by the poor was cut.[40]

The majority also approved special laws for disadvantaged regions of the Southern Italy. Such measures, although they could not even come close to bridging the north-south differences, gave appreciable results. This policy's aim was to improve the economic conditions of the farmers from the south.

1908 Messina earthquake

_-_Vittime_del_terremoto_di_Messina_(dicembre_1908).jpg.webp)

On 28 December 1908, a strong earthquake of magnitude of 7.1 and a maximum Mercalli intensity scale of XI, hit Sicily and Calabria. About ten minutes after the earthquake, the sea on both sides of the Strait suddenly withdrew a 12-meter (39-foot) tsunami swept in, and three waves struck nearby coasts. It impacted hardest along the Calabrian coast and inundated Reggio Calabria after the sea had receded 70 meters from the shore. The entire Reggio seafront was destroyed and numbers of people who had gathered there perished. Nearby Villa San Giovanni was also badly hit. Along the coast between Lazzaro and Pellaro, houses and a railway bridge were washed away. The cities of Messina and Reggio Calabria were almost completely destroyed and between 75,000 and 200,000 lives were lost.[41]

News of the disaster was carried to Prime Minister Giolitti by Italian torpedo boats to Nicotera, where the telegraph lines were still working, but that was not accomplished until midnight at the end of the day. Rail lines in the area had been destroyed, often along with the railway stations.[41]

The Italian navy and army responded and began searching, treating the injured, providing food and water, and evacuating refugees (as did every ship). Giolitti imposed martial law with all looters to be shot, which extended to survivors foraging for food. King Victor Emmanuel III and Queen Elena arrived two days after the earthquake to assist the victims and survivors.[41] The disaster made headlines worldwide and international relief efforts were launched. With the help of the Red Cross and sailors of the Russian and British fleets, search and cleanup were expedited.[42]

1909 election and resignation

In 1909 general election, Giolitti's Left gained 54.4% of votes and 329 seats out of 508.[43] Giolitti found himself faced with the necessity for renewing the steamship conventions which were about to lapse. The bill presented by his Cabinet on this subject was designed to conciliate conflicting politicaI interests rather than to solve the actual problem. The vigorous attacks of the conservative opposition, led by Baron Sidney Sonnino, induced Giolitti to adjourn the debate until the autumn, when, the Cabinet having been defeated on a point of procedure, he resigned on 2 December.[44] Giolitti proposed Sonnino as new prime minister, but after a few months, he withdrew his support for Sonnino's government and supported the moderate Luigi Luzzatti as new head of government. Given his party's position, Giolitti remained the real power.

After the premiership

Universal manhood suffrage

During Luzzatti's government the political debate had begun to focus on the enlargement of the right to vote. The Socialists, in fact, but also the Radicals and the Republicans, has long demanded the introduction of universal manhood suffrage, necessary in a modern liberal democracy. Luzzatti developed a moderate proposal with some requirements under which a person had the right to vote (age, literacy and annual taxes). The government's proposal was of a gradual expansion of the electorate, but without reaching the universal male suffrage.

Giolitti, speaking in the Chamber, declared himself in favor of universal male suffrage, overcoming the impulse to government positions. His aim was to cause Luzzatti's resignation and become prime minister again; moreover he want to start a cooperation with the Socialists in the Italian parliamentary system. Furthermore, Giolitti intended to extend his pre-war reforms. Conscripted men were fighting overseas in Libya and so it appeared as a symbol of national unity that they be given the vote.

Giolitti believed that the extension of the franchise would bring more conservative rural voters to the polls as well as drawing votes from grateful socialists.

Many historians considered Giolitti's proposal a mistake. Universal male suffrage, contrary to Giolitti's opinions, would destabilize the entire political establishment: the "mass parties," i.e. Socialist, Popular and later Fascist, were the ones who benefitted from the new electoral system. Giolitti "was convinced that Italy can not grow economically and socially without enlarging the number of those who partecipated [sic?] in public life."

Sidney Sonnino and the Socialists Filippo Turati and Claudio Treves proposed to introduce also female suffrage, but Giolitti strongly opposed it, considering it too risky, and suggested the introduction of female suffrage only at the local level.[45]

Fourth term as prime minister

Although a man of first-class financial ability, great honesty and wide culture, Luzzatti had not the strength of character necessary to lead a government: he showed lack of energy in dealing with opposition and tried to avoid all measures likely to make him unpopular. Furthermore, he never realized that with the chamber, as it was then constituted, he only held office at Giolitti's good pleasure. So on 30 March 1911 Luzzatti resigned from his office and King Victor Emmanuel III again gave Giolitti the task to form a new cabinet.

Social policy

During his fourth term, Giolitti tried to seal an alliance with the Italian Socialist Party, proposing the male universal suffrage, implementing left-wing social policies, introducing the National Insurance Institute, which provided for the nationalization of insurance at the expense of the private sector. Moreover, Giolitti appointed the socialist Alberto Beneduce as the head of this institute.[46] Law No.1361 of 1912 and the Royal Decree No. 431 that was approved in 1913 “represented the legal basis of the institutional activity of the Labour Inspectorate, still structured within the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade.”[47] In 1912 benefits were introduced were pregnant women and mothers.[48]

In 1912, Giolitti had the Parliament approve an electoral reform bill that expanded the electorate from 3 million to 8.5 million voters – introducing near-universal male suffrage – while commenting that first "teaching everyone to read and write" would have been a more reasonable route.[49] Considered his most daring political move, the reform probably hastened the end of the Giolittian Era because his followers controlled fewer seats after the 1913.[15]

During his ministry, the Parliament approved a law requiring the payment of a monthly allowance to deputies. In fact, at that time the parliamentarians had no type of salary, and this favoured the wealthy candidates.

Libyan War

The claims of Italy over Libya dated back to Turkey's defeat by Russia in the war of 1877–1878 and subsequent discussions after the Congress of Berlin in 1878, in which France and Great Britain had agreed to the occupation of Tunisia and Cyprus respectively, both parts of the then declining Ottoman Empire. When Italian diplomats hinted about possible opposition by their government, the French replied that Tripoli would have been a counterpart for Italy. In 1902, Italy and France had signed a secret treaty which accorded freedom of intervention in Tripolitania and Morocco;[50] however, the Italian government did little to realize the opportunity and knowledge of Libyan territory and resources remained scarce in the following years.

The Italian press began a large-scale lobbying campaign in favour of an invasion of Libya at the end of March 1911. It was fancifully depicted as rich in minerals, well-watered, and defended by only 4,000 Ottoman troops. Also, the population was described as hostile to the Ottoman Empire and friendly to the Italians: the future invasion was going to be little more than a "military walk", according to them.

The Italian government was hesitant initially, but in the summer the preparations for the invasion were carried out and Prime Minister Giolitti began to probe the other European major powers about their reactions to a possible invasion of Libya. The Socialist party had strong influence over public opinion; however, it was in opposition and also divided on the issue, acting ineffectively against military intervention.

An ultimatum was presented to the Ottoman government led by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) party on the night of 26–27 September. Through Austrian intermediation, the Ottomans replied with the proposal of transferring control of Libya without war, maintaining a formal Ottoman suzerainty. This suggestion was comparable to the situation in Egypt, which was under formal Ottoman suzerainty but was actually controlled by the United Kingdom. Giolitti refused, and war was declared on 29 September 1911. He was criticised for having declared war without consulting Parliament, and for not having summoned it until several months later. His conduct of the Government during the campaign was also severely criticised, as he acted as though the war were merely an affair of internal politics and party combinations.[44]

On 18 October 1912, Turkey officially surrendered. As a result of this conflict, Italy captured the Ottoman Tripolitania Vilayet (province), of which the main sub-provinces were Fezzan, Cyrenaica, and Tripoli itself. These territories together formed what became known as Italian Libya.

During the conflict, Italian forces also occupied the Dodecanese islands in the Aegean Sea. Italy had agreed to return the Dodecanese to the Ottoman Empire according to the Treaty of Ouchy[51] in 1912 (also known as the First Treaty of Lausanne (1912), as it was signed at the Château d'Ouchy in Lausanne, Switzerland.) However, the vagueness of the text allowed a provisional Italian administration of the islands, and Turkey eventually renounced all claims on these islands in Article 15 of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923.[52]

Although minor, the war was a precursor of World War I as it sparked nationalism in the Balkan states. Seeing how easily the Italians had defeated the weakened Ottomans, the members of the Balkan League attacked the Ottoman Empire before the war with Italy had ended.

The invasion of Libya was a costly enterprise for Italy. Instead of the 30 million lire a month judged sufficient at its beginning, it reached a cost of 80 million a month for a much longer period than was originally estimated. The war cost Italy 1.3 billion lire, nearly a billion more than Giolitti estimated before the war.[53] This ruined ten years of fiscal prudence.[53]

Foundation of the Liberal Union

In 1913, Giolitti founded the Liberal Union,[54] which was simply and collectively called Liberals. The Union was a political alliance formed when the Left and the Right merged in a single centrist and liberal coalition which largely dominated the Italian Parliament.

Giolitti had mastered the political concept of trasformismo, which consisted in making flexible centrist coalitions of government which isolated the extremes of the political left and the political right.

Gentiloni Pact

.tif.jpg.webp)

In 1904, Pope Pius X informally gave permission to Catholics to vote for government candidates in areas where the Italian Socialist Party might win. Since the Socialists were the arch-enemy of the Church, the reductionist logic of the Church led it to promote any anti-Socialist measures. Voting for the Socialists was grounds for excommunication from the Church.

When Pius X lifted the ban on Catholic participation in politics in 1913, and the electorate was expanded by a new franchise law from 3 million to 8 million,[44] he collaborated with the Catholic Electoral Union, led by Ottorino Gentiloni in the Gentiloni pact. It directed Catholic voters to Giolitti supporters who agreed to favour the Church's position on such key issues as funding private Catholic schools and blocking a law allowing divorce.[55]

The Vatican had two major goals at this point: to stem the rise of Socialism and to monitor the grassroots Catholic organizations (co-ops, peasant leagues, credit unions, etc.). Since the masses tended to be deeply religious but rather uneducated, the Church felt they were in need of conveyance so that they did not support improper ideals like Socialism or Anarchism. Meanwhile, Italian Prime Minister Giolitti understood that the time was ripe for cooperation between Catholics and the liberal system of government.

1913 election and resignation

A general election was held on 26 October 1913, with a second round of voting on 2 November.[43] Giolitti's Liberal Union narrowly retained an absolute majority in the Chamber of Deputies, while the Radical Party emerged as the largest opposition bloc. Both groupings did particularly well in Southern Italy, while the Italian Socialist Party gained eight seats and was the largest party in Emilia-Romagna;[56] however, the election marked the beginning of the decline of the Liberal establishment.

In March 1914, the Radicals of Ettore Sacchi brought down Giolitti's coalition, who resigned on 21 March.

World War I

After Gioilitti's resignation, the conservative Antonio Salandra was brought into the national cabinet as the choice of Giolitti himself, who still commanded the support of most Italian parliamentarians; however, Salandra soon fell out with Giolitti over the question of Italian participation in World War I. Giolitti opposed Italy's entry into the war on the grounds that Italy was militarily unprepared and he tried to use his personal hold over the parliamentary majority to upset the Salandra Cabinet, but was frustrated by an uprising of public opinion in favour of war.[44] At the outbreak of the war in August 1914, Salandra declared that Italy would not commit its troops, maintaining that the Triple Alliance had only a defensive stance and Austria-Hungary had been the aggressor. In reality, both Salandra and his ministers of Foreign Affairs, Antonino Paternò Castello, who was succeeded by Sidney Sonnino in November 1914, began to probe which side would grant the best reward for Italy's entrance in the war and to fulfil Italy's irredentist claims.[57]

On 26 April 1915, a secret pact, the Treaty of London or London Pact (Italian: Patto di Londra), was signed between the Triple Entente (the United Kingdom, France, and the Russian Empire) and the Kingdom of Italy. According to the pact, Italy was to leave the Triple Alliance and join the Triple Entente. Italy was to declare war against Germany and Austria-Hungary within a month in return for territorial concessions at the end of the war.[57] Giolitti was initially unaware of the treaty. His aim was to get concessions from Austria-Hungary to avoid war.[58]

While Giolitti supported neutrality, Salandra and Sonnino, supported intervention on the side of the Allies, and secured Italy's entrance into the war despite the opposition of the majority in parliament (see Radiosomaggismo). On 3 May 1915, Italy officially revoked the Triple Alliance. In the following days Giolitti and the neutralist majority of the Parliament opposed declaring war, while nationalist crowds demonstrated in public areas for entering the war. On 13 May 1915, Salandra offered his resignation, but Giolitti, fearful of nationalist disorder that might break into open rebellion, declined to succeed him as prime minister and Salandra's resignation was not accepted. On 23 May 1915, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary.[59]

On 18 May 1915, Giovanni Giolitti retired to Cavour and kept aloof from politics for the duration of the conflict. He consequently lost his influence over public opinion, and in many quarters was regarded as little better than a traitor.[44]

Fifth term as prime minister

Giolitti returned to politics after the end of the conflict. In the electoral campaign of 1919 he charged that an aggressive minority had dragged Italy into war against the will of the majority, putting him at odds with the growing movement of Fascists.[15] This election was the first one to be held with a proportional representation system, which was introduced by the government of Francesco Saverio Nitti.

Red Biennium

The election took place in the middle of Biennio Rosso ("Red Biennium") a two-year period, between 1919 and 1920, of intense social conflict in Italy, following the war.[60] The revolutionary period was followed by the violent reaction of the Fascist blackshirts militia and eventually by the March on Rome of Benito Mussolini in 1922.

The Biennio Rosso took place in the context of an economic crisis at the end of the war, with high unemployment and political instability. It was characterized by mass strikes, worker manifestations as well as self-management experiments through land and factory occupations.[60] In Turin and Milan, workers councils were formed and many factory occupations took place under the leadership of anarcho-syndicalists. The agitations also extended to the agricultural areas of the Padan plain and were accompanied by peasant strikes, rural unrests and guerrilla conflicts between left-wing and right-wing militias.

In the general election, the fragmented Liberal governing coalition lost the absolute majority in the Chamber of Deputies, due to the success of the Italian Socialist Party and the Italian People's Party.[56]

Giolitti became prime minister again on 15 June 1920, because he was considered the only one who could solve that dramatic situation. As he did before, he did not accept the demands of landowners and entrepreneurs asking the government to intervene by force. He succeeded in forming a cabinet which comprised a number of non-Giolittians of all parties, but only a few of his own old guard, so that he won the support of a considerable part of the parliament, although the Socialists and the Popolari (Catholics) rendered his hold somewhat precarious.[44]

To the complaints of Giovanni Agnelli, who intentionally described a dramatic and exaggerated situation of FIAT, which was occupied by workers, Giolitti replied: "Very well, I will give orders to the artillery to bomb it". After a few days, the workers spontaneously ceased the strike. The Prime Minister was aware that an act of force would have only aggravated the situation and also suspected that in many cases the entrepreneurs were linked to the occupation of factories by workers.

Fiume Exploit

Before entering the war, Italy had made a pact with the Allies, the Treaty of London, in which it was promised all of the Austrian Littoral, but not the city of Fiume. After the war, at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, this delineation of territory was confirmed, with Fiume remaining outside of Italian borders, instead joined with adjacent Croatian territories into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Moreover, Giolitti's last term saw Italy relinquish control over most of the Albanian territories it gained after World War I, following prolonged combat against Albanian irregulars in Vlorë.

The Italian nationalist and poet Gabriele D'Annunzio was angered by what he considered to be the handing over of the city of Fiume. On 12 September 1919, he led around 2,600 troops from the Royal Italian Army (the Granatieri di Sardegna), Italian nationalists and irredentists, into a seizure of the city, forcing the withdrawal of the inter-Allied (American, British and French) occupying forces. Their march from Ronchi dei Legionari to Fiume became known as the Impresa di Fiume ("Fiume Exploit").

On the same day, D'Annunzio announced that he had annexed the territory to the Kingdom of Italy. He was enthusiastically welcomed by the Italian population of Fiume.[61] The Italian government of Giolitti opposed this move. D'Annunzio, in turn, resisted pressure from Italy. The plotters sought to have Italy annexe Fiume but were denied. Instead, Italy initiated a blockade of Fiume while demanding that the plotters surrender.

The approval of the Treaty of Rapallo on 12 November 1920, between Italy and Yugoslavia, turned Fiume into an independent state, the Free State of Fiume. D'Annunzio ignored the Treaty of Rapallo and declared war on Italy itself. On 24 December 1920, Giolitti sent the Royal Italian Army to Fiume and ordered the Royal Italian Navy to bomb the city; these forced the Fiuman legionnaires to evacuate and surrender the city.

The Free State of Fiume would officially last until 1924, when Fiume was eventually annexed to the Kingdom of Italy under the terms of the Treaty of Rome. The administrative division was called the Province of Fiume.

1921 election and resignation

When workers' occupation of factories increased the fear of a communist takeover and led the political establishment to tolerate the rise of the fascists of Benito Mussolini, Giolitti enjoyed the support of the fascist squadristi and did not try to stop their forceful takeovers of city and regional government or their violence against their political opponents.

In 1921 Giolitti founded the National Blocs, an electoral list composed by his Liberals, the Italian Fasces of Combat led by Benito Mussolini, the Italian Nationalist Association led by Enrico Corradini, and other right-wing forces. Giolitti's aim was to stop the growth of the Italian Socialist Party.[62]

Giolitti called for new elections in May 1921, but his list obtained only 19.1% of votes and a total of 105 MPs. The disappointing results forced him to step down.[43]

Rise of Fascism

.jpg.webp)

Still the head of the liberals, Giolitti did not resist the country's drift towards Italian Fascism.[15] In 1921, he supported the cabinet of Ivanoe Bonomi, a social-liberal who led the Italian Reformist Socialist Party; when Bonomi resigned, the Liberals proposed again Giolitti as prime minister, considering him the only one who could save the country from civil war. The People's Party of Don Luigi Sturzo, which was the senior party in the coalition, strongly opposed him. On 26 February 1922, King Victor Emmanuel III gave Luigi Facta the task of forming a new cabinet. Facta was a Liberal and close friend of Giolitti.

When the Fascist leader Benito Mussolini marched on Rome in October 1922, Giolitti was in Cavour. On 26 October, former prime minister Antonio Salandra warned the then prime minister Facta that Mussolini was demanding his resignation and that he was preparing to march on Rome; however, Facta did not believe Salandra and thought that Mussolini would govern quietly at his side. To meet the threat posed by the bands of Fascist troops gathering outside Rome, Facta, who had resigned but continued to hold power, ordered a state of siege for Rome. Having had previous conversations with the king about the repression of fascist violence, he was sure the king would agree,[63] but Victor Emmanuel III refused to sign the military order.[64] On 28 October, the King handed power to Mussolini, who was supported by the military, the business class, and the right wing.[65][66]

Mussolini pretended to be willing to take a subalternate ministry in a Giolitti or Salandra cabinet but then demanded the Presidency of the Council. Giolitti supported Mussolini's government initially – accepting and voting in favour of the controversial Acerbo Law,[67] which guaranteed that a party obtaining at least 25 per cent and the largest share of the votes would gain two-thirds of the seats in parliament. He shared the widespread hope that the fascists would become a more moderate and responsible party upon taking power, but withdrew his support in 1924, voting against the law that restricted press freedom. During a speech in the Chamber of Deputies, Giolitti said to Mussolini: "For the love of your country, do not treat the Italian people as if they did not deserve the freedom they always had in the past!"[68]

In December 1925, the provincial council of Cuneo, in which Giolitti was re-elected president in August, voted a motion which asked him to join the National Fascist Party. Giolitti, who by that time completely opposed the regime, resigned from his office. In 1928 he spoke to the Chamber against the law which effectively abolished the elections, replacing them with the ratification of governmental appointments.

Death and legacy

Powerless, Giolitti remained in Parliament until his death in Cavour, Piedmont, on 17 July 1928. His last words to the priest were: "My dear father, I am old, very old. I served in five governments, I could not sing Giovinezza." Giovinezza, which means "youth", was the official anthem of the Fascist regime.[69]

According to his biographer Alexander De Grand, Giolitti was Italy's most notable prime minister after Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour.[9] Like Cavour, Giolitti came from Piedmont; like other leading Piedmontese politicians, he combined a pragmatism with an Enlightenment faith in progress through material advancement. An able bureaucrat, he had little sympathy for the idealism that had inspired much of the Risorgimento. He tended to see discontent as rooted in frustrated self-interest and believed that most opponents had their price and could be transformed eventually into allies.[30]

The primary objective of Giolittian politics was to govern from the political centre with slight and well-controlled fluctuations, now in a conservative direction, then in a progressive one, trying to preserve the institutions and the existing social order.[9] Critics from the political right considered him a socialist due to the courting of socialist votes in parliament in exchange for political favours; writing for the Corriere della Sera, Luigi Albertini mockingly described Giolitti as "the Bolshevik from the Most Holy Annunciation" after his Dronero speech advocating Italy's neutrality during World War I like the Socialists. Critics from the political left called him ministro della malavita ("Minister of the Underworld"), a term coined by the historian Gaetano Salvemini, accusing him of winning elections with the support of criminals.[6][9]

According to one study, Giolitti represented a new kind of liberalism, noting that

“Giolitti's ability to muster the votes in the Chamber for the reforms he deemed necessary established him as the undisputed political leader of Italy for over a decade. His program of reforms also made him the most significant Italian practitioner of European New Liberalism. Giolitti did not contribute theoretical works to this new intellectual current, but he put into practice several of the tenets of New Liberalism before some of the theorists of the intellectual current had shown awareness of them.”[70]

Giolitti stands out as one of the major liberal reformers of late 19th- and early 20th-century Europe alongside the French Georges Clemenceau (Independent Radicals) and the British David Lloyd George (Liberal Party). He was a staunch adherent of 19th-century elitist liberalism trying to navigate the new tide of mass politics. A lifelong bureaucrat aloof from the electorate, Giolitti introduced near universal male suffrage and tolerated labour strikes. Rather than reform the state as a concession to populism, he sought to accommodate the emancipatory groups, first in his pursuit of coalitions with socialist and Catholic movements, and at the end of his political life in a failed courtship with Italian Fascism.[9]

Antonio Giolitti, the post-war leftist politician, was his grandson.

Giolittian Era

Giolitti's policy of never interfering in strikes and leaving even violent demonstrations undisturbed at first proved successful, but indiscipline and disorder grew to such a pitch that Zanardelli, already in bad health, resigned, and Giolitti succeeded him as prime minister in November 1903.[17] Giolitti's prominent role in the years from the start of the 20th century until 1914 is known as the Giolittian Era, in which Italy experienced an industrial expansion, the rise of organised labour and the emergence of an active Catholic political movement.[6]

The economic expansion was secured by monetary stability, moderate protectionism and government support of production. Foreign trade doubled between 1900 and 1910, wages rose, and the general standard of living went up.[71] Nevertheless, the period was also marked by social dislocations.[15] There was a sharp increase in the frequency and duration of industrial action, with major labour strikes in 1904, 1906 and 1908.[6]

Emigration reached unprecedented levels between 1900 and 1914 and rapid industrialization of the North widened the socio-economic gap with the South. Giolitti was able to get parliamentary support wherever it was possible and from whoever was willing to cooperate with him, including socialists and Catholics, who had been excluded from government before. Although an anti-clerical he got the support of the catholic deputies repaying them by holding back a divorce bill and appointing some to influential positions.[15]

Giolitti was the first long-term Prime Minister of Italy in many years because he mastered the political concept of trasformismo by manipulating, coercing and bribing officials to his side. In elections during Giolitti's government, voting fraud was common, and Giolitti helped improve voting only in well-off, more supportive areas, while attempting to isolate and intimidate poor areas where opposition was strong.[72] Many critics accused Giolitti of manipulating the elections, piling up majorities with the restricted suffrage at the time, using the prefects just as his contenders; however, he refined the practice in the general elections of 1904 and 1909 that gave the Liberals secure majorities.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ La dittatura parlamentare di Giolitti, Tesi Online

- ↑ Amoore, The Global Resistance Reader, p. 39

- 1 2 Barański & West, The Cambridge Companion to Modern Italian Culture, p. 44

- 1 2 Killinger, The History of Italy, p. 127–28

- ↑ Coppa 1970

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sarti, Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present, pp. 46–48

- ↑ Health and Healthcare Policy in Italy Since 1861 A Comparative Approach By Francesco Taroni, 2022, P.22

- ↑ Coppa 1971

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 De Grand, The Hunchback's Tailor, pp. 4-5

- ↑ "Il ministro della malavita" di G. Salvemini

- ↑ "Il potere alla volontà della nazione: eredità di Giovanni Giolitti". Archived from the original on 2016-10-14. Retrieved 2017-02-13.

- ↑ Giovanni Giolitti, Memorie; p. 6

- ↑ Giovanni Giolitti, Memorie; p. 7

- 1 2 De Grand, The Hunchback's Tailor, p. 12

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sarti, Italy: a Reference Guide From the Renaissance to the Present, pp. 313-14

- ↑ Gentile, Emilio (2000). "Giolitti, Giovanni". In Ghisalberti, Alberto M. (ed.). Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Vol. 55: Ginammi-Giovanni da Crema. Rome, Italy: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. OCLC 163430158.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ Extra-parliamentary speeches p. 92

- ↑ Alfredo Gigliobianco and Claire Giordano, Economic Theory and Banking Regulation: The Italian Case (1861-1930s), Quaderni di Storia Economica (Economic History Working Papers), Nr. 5, November 2010

- 1 2 Seton-Watson, Italy from Liberalism to Fascism, pp. 154-56

- ↑ Pohl & Freitag, Handbook on the history of European banks, p. 564

- ↑ Duggan, The Force of Destiny, p. 340

- ↑ Fascio (plural: fasci) literally means "faggot", as in a bundle of sticks, but also "league", and was used in the late 19th century to refer to political groups of many different and sometimes opposing orientations.

- ↑ Shot Down by the Soldiers; Four of the Mob Killed in an Anti-Tax Riot in Sicily, The New York Times, December 27, 1893

- ↑ Sicily Under Mob Control; A Series of Antitax Riots in The Island, The New York Times January 3, 1894

- ↑ Cabinet Forced To Resign; Italian Ministers Called "Thieves" by the People, The New York Times, November 25, 1893

- ↑ De Grand, The Hunchback's Tailor, pp. 47-48

- ↑ Seton-Watson, Italy from Liberalism to Fascism, pp. 162-63

- ↑ Clark, Modern Italy: 1871 to the present, p. 141-42

- 1 2 Duggan, The Force of Destiny, pp. 362-63

- ↑ Brunello Vigezzi, Giolitti e Turati: un incontro mancato, Volume 1, R. Ricciardi, 1976 p.3

- ↑ Aldo Alessandro Mola, Storia della monarchia in Italia, Bompiani, 2002 p.74

- ↑ Labor Inspection in Italy by Mario Fasani

- ↑ Veditz, Charles William August (1910). Child-labor Legislation in Europe. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Child-labor Legislation in Europe By Charles William August Veditz, 1910, P.316

- ↑ Health and Healthcare Policy in Italy Since 1861 A Comparative Approach By Francesco Taroni, 2022, P.45

- ↑ Government Aid to Home Owning and Housing of Working People in Foreign Countries : Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, No. 158

- ↑ Gazzetta Ufficiale DEL REGNO D’ITALIA

- ↑ Foreign Crops and Markets. Bureau of Markets and Crop Estimates. 1935.

- ↑ The Hunchback's Tailor Giovanni Giolitti and Liberal Italy from the Challenge of Mass Politics to the Rise of Fascism, 1882-1922 By Alexander J. De Grand, 2001, P.135

- 1 2 3 Grifasi, A. "Sicily - The Messina 1908 earthquake". Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ↑ "Awards granted for service after the Messina Earthquake 1908". Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p1047 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chisholm 1922.

- ↑ Il diritto di voto delle donne in Italia fino al 1946

- ↑ Mimmo Franzinelli, Marco Magnani, Beneduce, il finanziere di Mussolini, Mondadori 2009, pp.34-36

- ↑ Labor Inspection in Italy by Mario Fasani

- ↑ Italy A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present By Roland Sarti, 2009, P.564

- ↑ De Grand, The Hunchback's Tailor, p. 138

- ↑ "Alliance System / System of alliances". thecorner.org. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ↑ "Treaty of Ouchy (1912), also known as the First Treaty of Lausanne". Archived from the original on 2021-10-25. Retrieved 2017-02-13.

- ↑ Full text of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)

- 1 2 Mark I. Choate: Emigrant nation: the making of Italy abroad, Harvard University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-674-02784-1, page 175.

- ↑ Gori, Annarita (2014). Tra patria e campanile. Ritualità civili e culture politiche a Firenze in età giolittiana. Franco Angeli Edizioni.

- ↑ Frank J. Coppa. "Giolitti and the Gentiloni Pact between Myth and Reality," Catholic Historical Review (1967) 53#2 pp. 217-228 in JSTOR

- 1 2 Piergiorgio Corbetta; Maria Serena Piretti, Atlante storico-elettorale d'Italia, Zanichelli, Bologna 2009. ISBN 978-88-080-6751-7

- 1 2 Baker, Ray Stannard (1923). Woodrow Wilson and World Settlement, Volume I, Doubleday, Page and Company, pp. 52–55

- ↑ Clark, Modern Italy: 1871 to the present, p. 221-22

- ↑ Mack Smith, Modern Italy: A Political History, p. 262

- 1 2 Brunella Dalla Casa, Composizione di classe, rivendicazioni e professionalità nelle lotte del "biennio rosso" a Bologna, in: AA. VV, Bologna 1920; le origini del fascismo, a cura di Luciano Casali, Cappelli, Bologna 1982, p. 179.

- ↑ Images of Fiume welcoming D'Annunzio Archived 2011-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Elenco candidati "Blocco Nazionale" Archived 2015-07-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Chiapello (2012), p.123

- ↑ Carsten (1982), p.64

- ↑ Carsten (1982), p.76

- ↑ T Gianni Toniolo, editor, The Oxford Handbook of the Italian Economy Since Unification, Oxford University Press (2013) p. 59; Mussolini's speech to the Chamber of Deputies on 26 May 1934

- ↑ De Grand, The Hunchback's Tailor, p. 251

- ↑ La Stampa, 11/18/1924, p.1

- ↑ Giovanni Giolitti, Dizionario Biografico

- ↑ Political Science Quarterly, Volume 86, No. 4 (December 1971), Giolitti’s Reform Program: An Exercise in Equilibrium Politics by Sándor Agócs, P.637

- ↑ Life World Library: Italy, by Herbert Kubly and the Editors of LIFE, 1961, p. 46

- ↑ Smith, Modern Italy; A Political History, p. 199

Notes

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Giolitti, Giovanni". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 31.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Giolitti, Giovanni". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 31 (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company. p. 283.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Giolitti, Giovanni". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 31 (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company. p. 283.

Bibliography

- Amoore, Louise (2005). The Global Resistance Reader, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-33584-1

- Barański, Zygmunt G. & Rebecca J. West (2001). The Cambridge Companion to Modern Italian Culture, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55034-3

- Clark, Martin (2008). Modern Italy: 1871 to the Present, Harlow: Pearson Education, ISBN 1-4058-2352-6

- Coppa, Frank J. (1970). "Economic and Ethical Liberalism in Conflict: The extraordinary liberalism of Giovanni Giolitti," Journal of Modern History (1970) 42#2 pp 191–215 in JSTOR

- Coppa, Frank J. (1967) "Giolitti and the Gentiloni Pact between Myth and Reality," Catholic Historical Review (1967) 53#2 pp. 217–228 in JSTOR

- Coppa, Frank J. (1971) Planning, Protectionism, and Politics in Liberal Italy: Economics and Politics in the Giolittian Age online edition

- De Grand, Alexander J. (2001). The Hunchback's Tailor: Giovanni Giolitti and Liberal Italy From the Challenge of Mass Politics to the Rise of Fascism, 1882-1922, Wesport/London: Praeger, ISBN 0-275-96874-X online edition

- Duggan, Christopher (2008). The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 0-618-35367-4

- Killinger, Charles L. (2002). The History of Italy, Westport (CT): Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-31483-7

- Mack Smith, Denis (1997). Modern Italy: A Political History, Ann Arbor (MI): Univ. of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-10895-4

- Pohl, Manfred & Sabine Freitag (European Association for Banking History) (1994). Handbook on the History of European Banks, Aldershot: Edward Elgar Publishing, ISBN 1-85278-919-0

- Salomone, A. William, Italy in the Giolittian Era: Italian Democracy in the Making, 1900-1914 (1945)

- Sarti, Roland (2004). Italy: a Reference Guide From the Renaissance to the Present, New York: Facts on File Inc., ISBN 0-81607-474-7

- Seton-Watson, Christopher (1967). Italy From Liberalism to Fascism, 1870-1925, New York: Taylor & Francis, 1967 ISBN 0-416-18940-7

- Smith, Denis Mack (1997). Modern Italy; A Political History, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-10895-6

.svg.png.webp)