| Battle of Beaver Dam Creek | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

_(14576177738).jpg.webp) Union troops repulsing a rebel charge | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 15,631[2] | 16,356[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

361 total 49 killed 207 wounded 105 missing[3] | 1,484[4] | ||||||

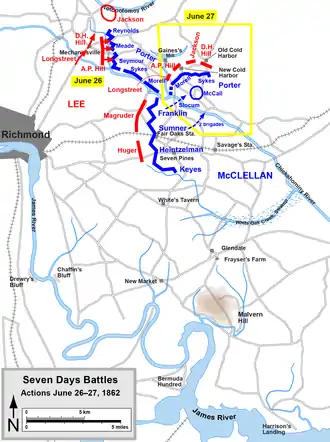

The Battle of Beaver Dam Creek, also known as the Battle of Mechanicsville or Ellerson's Mill, took place on June 26, 1862, in Hanover County, Virginia. It was the first major engagement[5] of the Seven Days Battles during the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the start of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's counter-offensive against the Union Army of the Potomac, under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, which threatened the Confederate capital of Richmond. Lee attempted to turn the Union right flank, north of the Chickahominy River, with troops under Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, but Jackson failed to arrive on time. Instead, Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill threw his division, reinforced by one of Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill's brigades, into a series of futile assaults against Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter's V Corps, which occupied defensive works behind Beaver Dam Creek. Confederate attacks were driven back with heavy casualties. Porter withdrew his corps safely to Gaines Mill, with the exception of Company F (a.k.a. The Hopewell Rifles) of the 8th Pennsylvania Reserve Regiment who did not receive the orders to retreat.

Background and Lee's plan

Military situation

After the Battle of Seven Pines, on May 31 and June 1, McClellan and the Army of the Potomac sat passively at the outskirts of Richmond for almost a month. Lee, newly appointed commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, devoted this period to reorganizing his army and preparing a counter-attack. He also sent for reinforcements. Stonewall Jackson arrived on June 25 from the Shenandoah Valley following his successful Valley Campaign. He brought four divisions: his own, now commanded by Brig. Gen. Charles S. Winder, and those of Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, Brig. Gen. William H. C. Whiting, and Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill.[6]

The Union Army straddled the rain-swollen Chickahominy River. Four of the Army's five corps were arrayed in a semicircular line south of the river. The V Corps under Brig. Gen. Porter was north of the river near Mechanicsville in an L-shaped line running north–south behind Beaver Dam Creek and southeast along the Chickahominy. Lee moved most of his army north of the Chickahominy to attack the Union north flank. He left only two divisions (under Maj. Gens. Benjamin Huger and John B. Magruder) to face the Union main body. This concentrated about 65,000 troops against 30,000, leaving only 25,000 to protect Richmond against the other 60,000 men of the Union army. It was a risky plan that required careful execution, but Lee knew that he could not win in a battle of attrition or siege against the Union army. The Confederate cavalry under Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart had reconnoitered Porter's right flank as part of a daring circumnavigation of the entire Union army from June 12 to June 15 and found it vulnerable. Stuart's forces burned a couple of Union supply ships and was able to report much of McClellan's army's strength and position to Gen. Lee. McClellan was aware of Jackson's arrival and presence at Ashland Station, but did nothing to reinforce Porter's vulnerable corps north of the river.[7]

Lee's plan called for Jackson to begin the attack on Porter's north flank early on June 26. Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill's Light Division was to advance from Meadow Bridge when he heard Jackson's guns, clear the Union pickets from Mechanicsville, and then move to Beaver Dam Creek. The divisions of Maj. Gens. D.H. Hill and James Longstreet were to pass through Mechanicsville, D.H. Hill to support Jackson and Longstreet to support A.P. Hill. Lee expected Jackson's flanking movement to force Porter to abandon his line behind the creek, and so A. P. Hill and Longstreet would not have to attack Union entrenchments. South of the Chickahominy, Magruder and Huger were to demonstrate, deceiving the four Union corps on their front.[8]

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Battle

Lee's intricate plan went awry immediately. Jackson's men, fatigued from their recent campaign and lengthy march, ran at least four hours behind schedule. By 3 p.m., A.P. Hill grew impatient and began his attack without orders. Hill's division, minus Brig. Gen Lawrence O'Bryan Branch's brigade, which was placed off to the north to link up with Jackson, entered Mechanicsville and skirmished with George McCall's Union division, deployed around the town. McCall fell back to an easily defensible spot on the opposite side of Beaver Dam Creek. There, the brigades of Brig. Gen John F. Reynolds and Brig. Gen Truman Seymour dug in, with Brig. Gen George G. Meade's brigade placed behind them in reserve, Reynolds' brigade to the north and Seymour's to the south. On Reynolds' right, the divisions of Brig. Gen George Morell and Brig. Gen George Sykes formed a semicircle. Supporting the roughly 26,000 Union infantrymen were 32 artillery pieces.[9] There, 14,000 well entrenched infantry, supported by 32 guns in six batteries, repulsed repeated Confederate attacks with substantial casualties.[10]

Jackson and his command arrived late in the afternoon. However, unable to find A.P. Hill or D.H. Hill, Jackson did nothing. Although a major battle was raging within earshot, he ordered his troops to make camp for the evening. Hill's 11,000 men, most of them green regiments who had never fired a shot in battle, launched a series of futile attacks over the next few hours. The brigade of John R. Anderson assaulted the Union right flank, with James Archer's and Charles W. Field's brigades in support. Maxcy Gregg's brigade was held in reserve and did not participate in the battle at all. Directing his troops, John Reynolds gestured at the oncoming mass of Confederates and told a staffer "There they come like flies on a piece of gingerbread." The Union artillery and musketry tore enormous gaps in the Confederate lines as they attempted to cross the creek. Although A.P. Hill had 24 guns with him, he made no attempt to use massed artillery fire to counter the Union gunners, instead sending individual batteries in support of the infantry, most of which were quickly put out of action by enemy shelling.[11]

Some of Anderson's men managed to get across the creek and momentarily threaten Reynolds's position, however he was reinforced by Meade's brigade and two regiments from Morell's division. The three Confederate brigades were driven back with substantial casualties. Arriving on the field and realizing what was happening, Robert E. Lee hastily summoned Longstreet's and D.H. Hill's divisions. As Lee surveyed the futile attacks, Jefferson Davis and the Confederate cabinet rode up to him. Davis asked him "General, what is all this army and what is it doing here?" Lee replied sarcastically "I don't know, Mr. President. It is not my army and this is no place for it." William D. Pender's brigade then attacked the Union left flank at Ellerson's Mill, held by Seymour's brigade. Once again, the well-entrenched infantry and massed artillery proved too much for the Confederates and Pender was forced to retreat. Just then, Roswell Ripley's brigade of D.H. Hill's division arrived on the field and was ordered next to assault the Union left. Ripley charged head-on into the Union entrenchments and suffered the very worst of all with over 600 casualties, the largest percentage of them coming from the 44th Georgia, which lost 335 men and most of its officers (out of a total of 514), including its colonel Robert A. Smith, a roughly 65% casualty rate. The 1st North Carolina suffered 50% casualties (133 men killed, wounded, or captured) and also lost its commander, Col. Montford Stokes. General Ripley himself survived unscathed, but came within inches of being decapitated by an artillery shell. Ripley's other two regiments, the 3rd North Carolina and 48th Georgia, were to the rear of the 1st North Carolina and 44th Georgia; their losses were lighter. Union casualties around Ellerson's Mill were small, only 40 men total were killed or wounded in the 7th Pennsylvania Reserves and 12th Pennsylvania Reserves, which were defending this sector of the battlefield. The 13th Pennsylvania Reserves lost 75 men, the highest total number of any Union outfit. Some 20 years after the battle, D.H. Hill wrote "The attacks on the Beaver Dam entrenchments, on the heights of Malvern Hill, at Gettysburg, were all grand, but of exactly the kind of grandeur the South could not afford."[12]

As darkness fell, the rest of D.H. Hill's division came up followed by Longstreet, while on the Union side, George Morrell's division arrived and relieved McCall, whose men were nearly out of ammunition. There was not enough daylight remaining to deploy D.H. Hill and Longstreet's divisions. Jackson did not attack, but his presence near Porter's flank caused McClellan to order Porter to withdraw after dark behind Boatswain's Swamp, five miles (8 km) to the east. McClellan was concerned that the Confederate buildup on his right flank threatened his supply line, the Richmond and York River Railroad north of the Chickahominy, and he decided to shift his base of supply to the James River (he also believed that the demonstrations by Huger and Magruder showed that he was seriously outnumbered). This was a strategic decision of grave import because it meant that, without the railroad to supply his army, he had to abandon his siege of Richmond.[13]

Aftermath

Overall, the battle was a Union victory "by any definition",[1] in which the Confederates suffered heavy casualties and achieved none of their specific objectives due to the seriously flawed execution of Lee's plan. Instead of over 60,000 men crushing the enemy's flank, only five brigades, about 15,000 men, had seen action. Their losses were 1,484 versus Porter's 361. Lee's staff recalled that he was "deeply, bitterly disappointed"[14] by Jackson's performance, but communication breakdowns, poorly written orders from Lee, and bad judgment by most of Lee's other subordinates were also to blame.[15]

Company F of the 8th Pennsylvania Reserve Regiment (also referred to as The Hopewell Rifles) from Bedford County, PA were not informed of the orders to retreat after being sent ahead to skirmish. They were consequently captured by the Confederates, and held as prisoners at both Belle Isle and Castle Thunder.

Despite the Union tactical success, however, it was the start of a strategic debacle and the unraveling of the Peninsula Campaign. McClellan began to withdraw his army to the southeast and never regained the initiative. The next day the Seven Days Battles continued as Lee attacked Porter at the Battle of Gaines's Mill.[16]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 US National Park Service. "The Battle of Beaver Dam Creek, June 26, 1862". Richmond National Battlefield Park Virginia. US National Park Service. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- 1 2 Eicher, p. 284.

- ↑ Eicher, pp. 284-85.

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 96; Eicher, p. 285.

- ↑ The Battle of Oak Grove is considered the start of the Seven Days, but it was a very minor battle in comparison to those that followed.

- ↑ Salmon, p. 96; Eicher, pp. 281-82.

- ↑ Sears, pp. 172, 195-97; Eicher, pp. 282-83.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 283; Sears, p. 194.

- ↑ Spelled Ellyson's Mill in The seven days' battles in front of Richmond. An outline narrative of the series of engagements which opened at Mechanicsville, near Richmond, on Thursday, June 26, 1862. Columbia, SC: Townsend & North. 1862. p. 6. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 284; Salmon, pp. 99-100.

- ↑ Salmon, p. 101.

- ↑ "Extraordinary Circumstances: The Seven Days Battles", Brian K. Burton, 2010

- ↑ Salmon, pp. 100-01; Eicher, pp. 283-84.

- ↑ Sears, p. 208.

- ↑ Sears, pp. 208-09; Eicher, pp. 284-85.

- ↑ Sears, p. 209; Salmon, p. 101.

References

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- Sears, Stephen W. To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign. Ticknor and Fields, 1992. ISBN 0-89919-790-6.

- National Park Service battle description

Further reading

External links

- The Battle of Beaver Dam Creek: Battle maps, history articles, photos, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)

- CWSAC Report Update