| Battle of Killiecrankie | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Jacobite Risings | |||||||

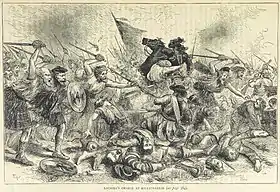

Lochiel's charge at Killycrankie by James Grant | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Hugh Mackay Barthold Balfour † |

Viscount Dundee † Ewen Cameron Alexander Cannon Alexander Fraser † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,600 – 5,100 men | 2,440 – 3,000 men [1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,700 – 2,000 killed, wounded and missing | 700 killed and wounded | ||||||

| Designated | 21 March 2011 | ||||||

| Reference no. | BTL12 | ||||||

The Battle of Killiecrankie (Scottish Gaelic: Blàr Choille Chnagaidh), also referred to as the Battle of Rinrory, took place on 27 July 1689 during the 1689 Scottish Jacobite rising. An outnumbered Jacobite force under Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel and John Graham, Viscount Dundee, defeated a government army commanded by General Hugh Mackay.

James VII went into exile in December 1688 after being deposed by the Glorious Revolution in Scotland. In March 1689, he began the Williamite War in Ireland, with a simultaneous revolt led by Dundee, previously military commander in Scotland.

Hampered by lack of men and resources, Dundee gambled on a decisive battle which he hoped would attract wider support. Although Killiecrankie was an unexpected and stunning victory, his army suffered heavy casualties and he was killed in the final minutes. It did little to change the overall strategic position, and the Jacobites were unable to take advantage of their success.

Background

In February 1685, the Catholic James II & VII came to power with widespread support; the 1638-to-1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms meant many in both England and Scotland feared the consequences of bypassing the 'natural heir'. A desire for stability led to the rapid collapse of the Monmouth Rebellion and Argyll's Rising in June 1685, both led by Protestant dissidents.[2]

By 1680, over 95% of Scots belonged to the Church of Scotland, or the Kirk; Catholics numbered less than 2% of the population and even other Protestant sects were barred.[3] The 1681 Scottish Test Act required holders of public office to be members of the Kirk; James' attempts to repeal it undermined his own supporters, while rewarding the extreme Presbyterians who backed Argyll in 1685.[4]

In June 1688, two events turned dissent into a crisis, the first being the birth of James Francis Edward on 10 June. This created the prospect of a Catholic dynasty, rather than James being succeeded by his Protestant daughter Mary, and her husband William of Orange. The second was the prosecution of the Seven Bishops, which seemed to extend official policy beyond mere tolerance for Catholicism to an assault on the established church. Their acquittal on 30 June destroyed James' political authority in both Scotland and England.[5]

In 1685, many feared a return to civil war if James were bypassed; by 1688, anti-Catholic riots made it seem only his removal could prevent one.[6] William landed in Brixham on 5 November with 14,000 men; as he advanced, James' army deserted, and he went into exile on 23 December. The Parliament of England offered the English throne to William and Mary in February 1689.[7]

On 14 March, a Convention met in Edinburgh to agree a settlement for Scotland. The Convention was dominated by supporters of the new administration, with 'Jacobites' restricted to those linked to James by religion or personal ties.[8] However, the number of activists on either side was tiny, the vast majority being unenthusiastic about either option. On 12 March, James landed in Ireland, and the Convention offered the Scottish throne to William and Mary on 11 April. On the following day, Dundee raised the Royal Standard on Dundee Law.[9]

Initial military actions

William's military commander in Scotland was General Hugh Mackay, head of the veteran Dutch Scots Brigade. His force of 3,500 included the Brigade regiments of Mackay, Balfour and Ramsay, the English Hastings Regiment and two newly raised Scots units. When Ewen Cameron of Lochiel learned of William's landing, he began recruiting men to fight for James; but the short-term nature of clan warfare meant they needed to be put to use as soon as possible.[10]

In April, Dundee joined him at Glenroy and on 18 May, took his force of around 1,800 Highlanders and attempted to bring Mackay to battle. He failed to do so and returned in June, after which most of the clansmen went home, leaving him with less than 200 men.[11] On 27 June, Dundee wrote to the Earl of Melfort asking for reinforcements; the loss of Kintyre after the Battle of Loup Hill made resupply from Ireland extremely difficult, and the letter details alternative landing spots. As time went on, his position weakened due to continued defections – the surrender of Edinburgh Castle on 14 June being especially discouraging.[12]

His requests for additional resources were denied, partly due to an internal dispute with the Catholic 'Non-Compounders', who dominated James's court in Ireland and urged him to refuse any concessions to regain his throne. Dundee and other Scottish Jacobites were mostly Protestant 'Compounders', for whom concessions were essential, and thus viewed with suspicion. The only reinforcements sent to Scotland were 300 Irish soldiers under the Catholic Alexander Cannon, who landed near Duart Castle on 21 July.[13]

A 'Jacobite' garrison under Patrick Stewart of Ballechin occupied Blair Castle, a strategic point controlling access to the Lowlands and seat of John Murray, 1st Marquess of Atholl. This illustrates how many families balanced both sides; claiming ill-health, Atholl went to England, leaving his eldest son, John Murray, to 'besiege' his ancestral home. Stewart himself was a trusted family retainer and one of Atholl's key lieutenants in the suppression of Argyll's Rising in 1685.[14]

In late July, Jacobite reinforcements arrived at Blair; Murray withdrew and Mackay moved north to support him, with somewhere between 3,600 and 5,100 troops. Seeing a chance to intercept, Dundee set out with his available forces, ordering the clans to follow "with all haste." Lochiel's sons were sent to raise additional levies; he and 240 Camerons plus Cannon's Irish contingent reached Blair on 26 July.[15]

Battle

.jpg.webp)

On the morning of 27 July, Dundee learned Mackay's forces were entering the Pass of Killiecrankie, a track nearly 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) long with the River Garry on the left and steep hills on either side. Sir Alexander McLean and 400 men were sent to skirmish with the advance guard, while Dundee assembled the rest of his troops on the lower slopes of Creag Eallich, north of the pass. As they advanced into the pass, the government army had the Jacobites on the high ground above and the river behind, while the narrow track made advance or retreat equally hazardous. Mackay halted, moved off the track and deployed his troops facing uphill in a long line, only three men deep, to maximise firepower.[16]

Mackay's force included Balfour, Ramsay and Mackay's regiments of the Scots Brigade, along with the newly raised regiments of Kenmure and Leven, part of Hastings' regiment, and 100 cavalry. As the most experienced, the Scots Brigade under Balfour and Lauder was placed on the left, which provided the best field of fire.[17]

The Jacobites formed into columns and were in position by late afternoon but Dundee waited until sunset, just after 8:00 pm to begin his attack. Balfour's front line fired three volleys, killing nearly 600 Highlanders but their fire was partly masked by a shallow terrace on the hillside, while the regiments to their right apparently fled without firing a shot.[18] Following their usual tactics, the Highlanders fired a single volley at 50 metres, dropped their muskets, and using axes and swords crashed into Mackay's centre.[19]

Killiecrankie is the first recorded use by British troops of the plug bayonet, which increased firepower by eliminating pikemen. It was 'plugged' into the musket barrel, preventing further reloading or firing, so fixing them was delayed until the last possible moment. Inexperience in their use and the speed of the Highland charge left the government troops defenceless and many fled, abandoning Balfour, who was killed along with James Mackay, Hugh's younger brother.[20]

Aftermath

Mackay managed to reform Hastings and Leven's regiments from the centre and right; some 800 men made it back to Stirling with relative ease, while others straggled in over the next few days. The Highlanders halted their pursuit to loot the baggage train, and their own casualties were enormous, with between 600 and 800 wounded or killed, the vast majority on the government left. Dundee was fatally wounded towards the end of the battle, and died shortly afterwards; a letter sent under his name to James reporting the victory is generally thought to be a forgery, although it provides a useful summary of the action.[21]

Based on muster rolls before and after the battle, government losses were around 2,000 killed, wounded or missing, although some of the "missing" may well have deserted. As colonels were paid for the number of men in their regiment, there was an obvious temptation to over-report pre-battle figures, but it is possible they suffered losses of up to 50%.[22]

Alexander Cannon took over as leader, and while not as talented a commander as Dundee, he faced the same problems; without siege equipment, he could not capture a port, making resupply almost impossible, while lack of cavalry made them vulnerable in the open. In addition, his most reliable unit, the Camrons, suffered particularly heavy casualties, while many other Highlanders went home with their loot. These factors meant time was on Mackay's side, so long as he avoided another ambush.[20]

After an assault on Dunkeld in August was repulsed with heavy losses, Cannon ended the campaign. Mackay spent the winter reducing Jacobite strongholds and constructing a new base at Fort William, while harsh weather conditions led to severe food shortages.[23] When Thomas Buchan replaced Cannon in February 1690, he could only mobilise some 800 men; he was taken by surprise at Cromdale in May and his forces scattered. Mackay pursued him into Aberdeenshire and in November 1690 relinquished command to Livingstone.[24]

In 2004, a fragment of a hand grenade was found, providing evidence of their first use in Britain 30 years earlier than that previously recorded at Glen Shiel in 1719.[25] A detailed survey carried out in 2015 confirmed the location and intensity of the close-quarter fighting, along with the discovery of large numbers of pistol and musket balls.[26]

References

- ↑ The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Killiecrankie (PDF). Edinburgh: Historic Scotland. 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ↑ Miller 1978, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Baker 2009, pp. 290–291.

- ↑ Harris 2007, pp. 153–157.

- ↑ Harris 2007, pp. 235–236.

- ↑ Womersley 2015, p. 189.

- ↑ Harris 2007, pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Coward 1980, p. 459.

- ↑ Lenman 1995, pp. 35–38.

- ↑ Fritze & Robison 1996, p. 68.

- ↑ Macpherson 1775, pp. 357–358.

- ↑ Macpherson 1775, pp. 360–366.

- ↑ Szechi 1994, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Kennedy 2016, p. 8.

- ↑ Lenman 1995, p. 48.

- ↑ Macpherson 1775, pp. 369–371.

- ↑ Mackay 1836, pp. 52–54.

- ↑ Oliver & Pollard 2003, p. 214.

- ↑ Hill 1986, p. 72.

- 1 2 Hill 1986, p. 73.

- ↑ Macpherson 1775, pp. 372–373.

- ↑ Guy 1985, pp. 33–35.

- ↑ Lenman 1995, p. 37.

- ↑ Chichester 2004.

- ↑ Ferguson 2016.

- ↑ Guard Archaeology 2016.

Sources

- Chichester, H.M. (2004). "Livingstone, Thomas, Viscount Teviot". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16810. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Baker, Derek (2009). Schism, Heresy and Religious Protest. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521101783.

- Coward, Barry (1980). The Stuart Age 1603–1714. Longman. ISBN 0582488338.

- Ferguson, Brian (5 March 2016). "Dozens of Battle of Killiecrankie artefacts unearthed at A9 roadworks". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- Fritze, Ronald; Robison, William (1996). Historical Dictionary of Stuart England, 1603–1689. Greenwood. ISBN 0313283915.

- Guard Archaeology (2016). "Significant finds made at Killiecrankie battle site - Scottish archaeology". History Scotland. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Guy, Alan (1985). Economy and Discipline: Officership and the British Army, 1714–63. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-1099-6.

- Harris, Tim (2007). Revolution; the Great Crisis of the British Monarchy 1685-1720. Penguin. ISBN 978-0141016528.

- Hill, James (1986). Celtic Warfare 1595–1763 (2017 ed.). Dalriada Publishers. p. 73. ISBN 097085255X.

- Kennedy, Allan (2016). "Rebellion, Government and the Scottish Response to Argyll's Rising of 1685" (PDF). Journal of Scottish Historical Studies. 36 (1): 40–59. doi:10.3366/jshs.2016.0167.

- Lenman, Bruce (1995). The Jacobite Risings in Britain, 1689–1746. Scottish Cultural Press. ISBN 189821820X.

- Mackay, John (1836). Life of Lieut.-Gen. Hugh Mackay of Scoury: Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in Scotland, 1689 and 1690 (2017 ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 1333263538.

- Macpherson, James (1775). Original Papers: Containing the Secret History of Great Britain (2017 ed.). Hansebooks. ISBN 3743435721.

- Miller, John (1978). James II: A study in kingship. Methuen. ISBN 978-0413652904.

- Oliver, Neil; Pollard, Tony (2003). Two Men in a Trench II: Uncovering the Secrets of British Battlefields (2015 ed.). Penguin. ISBN 0141012129.

- "First grenade found at Killiecrankie". The Scotsman. 22 February 2004. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688–1788. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719037743.

- Womersley, David (2015). James II: The Last Catholic King. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0141977065.