| Battle of Pharos | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

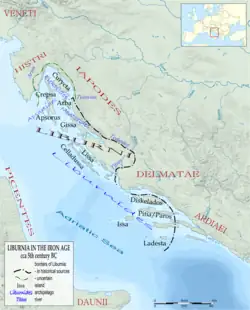

Liburnia in the 5th century BC | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Liburnians (Iadasinoi from present-day Zadar, and others) | Syracusan Greeks | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Unknown | Dionysius I of Syracuse | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

10,000 men 300 liburna ships | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

More than 5,000 killed 2,000 prisoners | Unknown | ||||||

The Battle of Pharos was a naval battle between the Greek colony of Pharos which was allied with Dionysius I of Syracuse and the Liburnians. The battle took place during 384–383 BC. The Liburnians of Zadar, the Iadasinoi, became allies of the natives of Hvar and the leaders of an eastern Adriatic coast coalition in the fight against the Greek colonizers. An expedition of 10,000 men in 300 ships sailed out from Zadar and laid siege to the Greek colony Pharos in the island of Hvar, but the Syracusan fleet of Dionysius was alerted and attacked the siege fleet. The naval victory went to the Greeks which allowed them to further colonize the southern Adriatic coast in relative safety.[1]

Background

The fall of Liburnian domination in the Adriatic Sea and their final retreat to their ethnic region (Liburnia) were caused by the military and political activities of Dionysius the Elder of Syracuse. The imperial power base of this Syracusan tyrant stemmed from a huge naval fleet of 300 tetreras and penteras. After Dionysius of Syracuse and the Carthaginian general, Mago, agreed to a peace treaty (392 BC) defining their areas of control across Sicily, Dionysius turned against the Etruscans. He made use of the Celtic invasion of Italy, and the Celts became his allies in the Italian peninsula (386–385 BC). This alliance was crucial for his politics, then focusing on the Adriatic Sea, where the Liburnians still dominated. In light of this strategy, he established a few Syracusan colonies on the coasts of the Adriatic Sea: Adria at the mouth of Po river and Ancona at the western Adriatic coast, Issa on the outermost island of the central Adriatic archipelago (island of Vis) and others. Meanwhile, in 385–384 BC he helped colonists from the Greek island of Paros to establish Pharos (Starigrad) colony on the Liburnian island of Hvar, thus taking control of the important points and navigable routes in the southern, central and northern Adriatic.

Battle

This caused a simultaneous Liburnian resistance on both coasts, whether in their ethnic domain or on the western coast, where their possessions or interests were in danger. The naval battle of Pharos was recorded a year after the establishment of the colony, by a Greek inscription in Pharos (384–383 BC) and by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (80–29 BC); initiated by conflicts between the Greek colonists and the indigenous Hvar islanders, who asked their compatriots for support. 10,000 Liburnians sailed out from their capital Idassa (Zadar), led by the Iadasinoi (people of Zadar), and laid siege to Pharos. The Syracusan fleet positioned in Issa was informed in time, and Greek triremes attacked the siege fleet, taking victory in the end. According to Diodorus, the Greeks killed more than 5,000 and captured 2,000 prisoners, ran down or captured their ships, and burned their weapons in dedication to their god.[2][3]

Diodorus (15.14) records the following:

This year the Parians who had settled on Pharos allowed the previous barbarian inhabitants to remain unharmed in a well fortified place, while they themselves built their city by the sea and enclosed it with a wall. Later the earlier inhabitants took offence at the presence of the Greeks and called in the Illyrians dwelling on the mainland opposite. These crossed to Pharos in a large number of small boats and, more than en thousand strong, killed many Greeks and did much damage. However Dionysius' commander at Lissus sailed up with a large number of Triremes against the Illyrian light craft and, having sunk some and captured others, killed more than five thousand of the barbarians and took around two thousand prisoners.

Aftermath

This battle meant the loss of the most important strategic Liburnian positions in the centre of the Adriatic, resulting in their final retreat to their main ethnic region, Liburnia, and their complete departure from the Italic coast, apart from Truentum (nowadays on the border between Marche and Abruzzo). Greek colonization, however, did not extend into Liburnia, which remained strongly held, and Syracusan dominance suddenly diminished upon the death of Dionysius the Elder.[4]

References

- ↑ M. Suić, Prošlost Zadra I, Zadar u starom vijeku, Filozofski fakultet Zadar, 1981, pages 127-130

- ↑ John Wilkes - The Illyrians

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-20. Retrieved 2013-12-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ M. Zaninović, Liburnia Militaris, Opusc. Archeol. 13, 43-67 (1988), UDK 904.930.2(497.13)>>65<<, pages 49 -53