Delminium was an Illyrian city and the capital of Dalmatia which was located somewhere near today's Tomislavgrad, Bosnia and Herzegovina, under which name it also was the seat of a Latin bishopric (also known as Delminium).[1]

Name

The toponym Delminium has the same root as the tribal name Dalmatae and the regional name Dalmatia.[1][2][3] It is considered to be connected to the Albanian dele and its variants which include the Gheg form delmë, meaning "sheep", and to the Albanian term delmer, "shepherd".[4][5][6][7][8][9] According to Orel, the Gheg form delme hardly has anything in common with the name of Dalmatia because it represents a variant of dele with *-mā, which is ultimately from proto-Albanian *dailā.[10] The ancient name Dalmana, derived from the same root, testifies to the advance of the Illyrians into the middle Vardar, between the ancient towns of Bylazora and Stobi.[9] The medieval Slavic toponym Ovče Pole ("plain of sheep" in South Slavic) in the nearby region represents a related later development.[9] In Albania, Delvinë represents a toponym linked to the root *dele.[7]

The form Dalmatae and the respective regional name Dalmatia are later variants as is already noted by Appian (2nd century AD). His contemporary grammarian Velius Longus highlights in his treatise about orthography that the correct form of Dalmatia is Delmatia, and notes that Marcus Terentius Varro who lived about 2 centuries prior of Appian and Velius Longius, used the form Delmatia as it corresponded to the chief settlement of the tribe, Delminium.[11] The toponym Duvno is a derivation from Delminium in Croatian via an intermediate form *Delminio in late antiquity.[3]

Historical research

The location of the ancient Delminium near the present-day Tomislavgrad was first reported by Karl Patsch. He based his conclusion on archeological research between 1896 and 1898, which located ancient settlements in Crkvina and Karaula in Tomislavgrad. Patsch located Delminium 9 km southeast from Tomislavgrad at the Lib mountain. Patsch's conclusion was soon accepted by many other notable researchers, including Ferdo Šišić, Vladimir Ćorović, Ćiro Truhelka and others.[12]

Based on the position of Delminium and its strength and resistance to the Roman military, Patsch concluded that Delminium served as a centre of the Dalmatae. These observations were based on the writings of Strabo, Appian and Florus.[13]

The area has been inhabited by the Illyrian tribe of Dalmatae[14] and Delminium was a town established by them near present-day Tomislavgrad.[15]

The area of Tomislavgrad was populated even before Illyrians arrived, as attested by a few remains of polished stone axes dating from the Neolithic (4000 BC – 2400 BC).[16] Similarly few remains date from the ensuing Bronze Age (1800 BC – 800 BC): 34 bronze sickles, 3 axes and 2 spears found in Stipanjići and Lug near Tomislavgrad, and a bronze axe found in Letka, was kept at the archaeological collection at the monastery in Široki Brijeg, which was destroyed in a fire by communists at the end of World War II. Only one sickle and one axe survived the blaze. Those findings attest that the population of the area at the time were cattlemen, farmers and warriors.[17]

The material remains of Illyrians are much more abundant. On the slopes of the mountains which circle Tomislavgrad, Illyrians built a total of 21 forts which served as watchtowers and defensive works.[18] There are also many Illyrian burial sites dating from the Bronze and the Iron Age to the Roman conquest. The grave goods recovered include jewelry and other items.[16] Apart from Illyrians, other inhabitants of the area included Celts, whose incursions into the Balkans began in 4th century BC. They brought higher culture, crafts and better weapons.[19] The Celts were few in number and were soon assimilated into the Illyrians.[19]

As Romans conquered the territory of the Illyrian tribe Ardiaei to the south, the Delmatae and their tribal union were among the last bastions of Illyrian autonomy. Dalmataes attacked Roman guard posts near the Neretva, Greek merchant towns, and the Roman-friendly Illyrian tribe Daorsi. They upgraded their settlement into a strong fort and surrounded their capital with a ring of smaller forts.[19] The reports of writers from that time say that Delminium was a "large city", almost inaccessible and impregnable. It is assumed that at this time 5,000 Dalmataes lived in Delminium.[19]

In 167 BC the Illyrian forts were unable to stop Roman legions; after the Romans conquered the whole Adriatic coast south of the Neretva and after the state of the Ardieaei was destroyed, the Dalmatae were unable to avoid conflict with Romans. In 156 BC, the first conflict between the Dalmatae and the Romans took place, ending the following year in defeat for the Delmatae. Roman generals Figulus and Cornelius Scipio Nasica conquered, destroyed and burned Delminium, reportedly firing burning arrows at wooden houses.[19] After various revolts led by the Dalmatae and three wars between them and the Romans, their resistance was finally quelled in the Great Illyrian revolt that ended in 9 AD.

Roman rule

After the Roman conquest of Delminium, Romans started building roads and bridges. Roads that led to the mainland of the Balkans from the Adriatic coast in Salona (Solin) and Narona (Vid near Metković) crossed in Delminium (Tomislavgrad). Remains of those and other Roman roads are still in existence. Romans introduced their culture, language, legislation and religion. For the next 400 years, Delminium was in peace.[20]

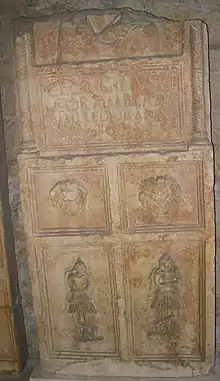

After the Romans finally defeated Dalmataes, Tomislavgrad was almost abandoned. There was also, for some period, a military crew of Romans stationed there to keep Illyrians under control. Romans started to rebuild Delminium in 18 and 19 AD during the time of Emperor Tiberius. During that time, center of the city was built, a Roman forum. This forum was built on possession of the present-day Nikola Tavelić basilica.[21] In 1896 Fra Anđeo Nunić discovered various sculptures of Roman deities, fragments of sarcophagi, and fragments of columns of the medieval Christian church. From all those discoveries, the most prominent are two votive monuments and altars dedicated to goddess Diana, one altar dedicated to native Illyrian god Armatus and one votive plate dedicated to goddess Libera. Later, a relief of the goddess Diana was also found and one relief of Diana and Silvanus together. Also, new altars, fragments of sarcophagi, clay pottery, parts of columns, and various other findings from the Roman and early medieval ages were found. This led to the conclusion that in place of the present-day Catholic graveyard "Karaula" (which was previously an Ottoman military border post and guardhouse) was Roman and Illyrian sanctuary and graveyard.[22]

In 1969, a tablet, which was part of an altar, was found near the village Letka. It is dedicated to the Roman god of war, Mars by a soldier of the 9th Legion. A year later, in the village Prisoje, a Christian font was found and part of a tomb, made by father Juvenal to his son Juvenal.[22]

After Roman Empire

Roman Delminium survived for two centuries during the great migrations. During that time, Delminium was partly damaged and somewhere in the middle 5th century, the Roman Forum was destroyed.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire in 476, Delminium was ruled by the Germanic Goths between 493 and 537. After Delminium came under Byzantine Empire in 573, the city was fully recovered. But, soon it was again highly damaged by new arrivals and deducted from the Byzantine Empire in 600.[22]

In middle of 7th century, Delminium was inhabited by Croats.[22]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 Wilkes, John (1996). The Illyrians. Wiley. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-631-19807-9.

The coast and hinterland of central Dalmatia up to and beyond the Dinaric mountains was inhabited by the Delmatae, after whom the Roman province Dalmatia was named, their own name being derived from their principal settlement Delminium near Duvno.

- ↑ Stipcevic, Aleksandar; Stipčević, Aleksandar (1977). The Illyrians: History and Culture. Noyes Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-8155-5052-5.

- 1 2 Šimunović, Petar (2013). "Predantički toponimi u današnjoj (i povijesnoj) Hrvatskoj". Folia onomastica Croatica (in Croatian) (22): 164. ISSN 1330-0695.

- ↑ Wilkes, John (1996). The Illyrians. Wiley. p. 244. ISBN 9780631146711.

The name of the Delmatae appears connected with the Albanian word for 'sheep' (delmë)

- ↑ Duridanov, Ivan (2002). "Illyrisch". In Bister, Feliks J.; Gramshammer-Hohl, Dagmar; Heynoldt, Anke (eds.). Lexikon der Sprachen des europäischen Ostens (PDF) (in German). Wieser Verlag. p. 952. ISBN 978-3-85129-510-8.

Δάλμιον, Δελμίνιον (Ptolemäus) zu alb. delmë

- ↑ Šašel Kos, Marjeta (1993). "Cadmus and Harmonia in Illyria". Arheološki Vestnik. 44: 113–136.

In the prehistoric and classical periods it was not at all unusual for peoples to have names derived from animals, such that the name of the Delmatae is considered to be related to Albanian delme, sheep

- 1 2 Schütz, István (2006). Fehér foltok a Balkánon (PDF) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Balassi Kiadó. p. 127. ISBN 9635064721.

A dalmata/delmata illír törzs, Dalmatia/Delmatia terület, Delminium/Dalmion illír város neve, továbbá a mai Delvinë és Delvinaqi földrajzi tájegység neve az albán dele (többese delme) 'juh', delmer 'juhpásztor' szavakhoz kapcsolódik. Strabon Delmion illír város nevéhez ezt az éretelmezést fűzi „...πεδιον µελωβοτον...", azaz „juhokat tápláló síkság"

- ↑ Morić, Ivana (2012). "Običaji Delmata". Rostra: Časopis studenata povijesti Sveučilišta u Zadru (in Croatian). 5 (5): 63. ISSN 1846-7768.

danas još uvijek prevladava tumačenje kako korijen njihova imena potječe od riječi koja je srodna albanskom delë, delmë odnosno „ovca"

- 1 2 3 Duridanov, Ivan (1975). Die Hydronymie des Vardarsystems als Geschichtsquelle (PDF). Böhlau Verlag. p. 25. ISBN 3412839736.

- ↑ Orel, Vladimir (1998). Albanian Etymological Dictionary. Brill Publishers. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-9004110243.

dele f, pl dele, dhen, dhën 'sheep'. The Geg variant delme represents a formation in *-mā (and hardly has anything in common with the name of Dalmatia pace MEYER Wb. 63 and ÇABEJ St. I 111). The word is based on PAlb *dailā 'sheep' < 'suckling' and related to various l-derivatives from IE *dhē(i)- 'to suckle' (MEYER Wb. 63, Alb. St. Ill 29 operates with *dailjā < IE *dhailiā or *dhoiliā), cf., in particular, Arm dayl 'colostrum' < IE *dhailo-.

- ↑ Kos, Marjeta Šašel (2005). Appian and Illyricum. Narodni muzej Slovenije. ISBN 978-961-6169-36-3.

- ↑ Škegro 2000, p. 396.

- ↑ Škegro 2000, p. 398.

- ↑ Wilkes 2000, p. 597.

- ↑ Wilkes 1992, p. 188.

- 1 2 (in Croatian) Bagarić, Ivo. Duvno: Povijest župa duvanjskog samostana. Sveta baština. 1989

- ↑ Bagarić 1980, p. 9.

- ↑ Bagarić 1980, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bagarić, Ivo (1980). Duvno - Short Monograph (in Croatian). Bukovica: Župni ured sv. Franje Asiškog. OCLC 255541281.

- ↑ Bagarić 1980, p. 12.

- ↑ Bagarić 1980, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 Bagarić 1980, p. 14.

Bibliography

- Škegro, Ante (1 January 2000). "Dalmion / Delmion i Delminium - kontroverze i činjenice. Dalmion / Delmion and Delminium: controversy and facts". Opuscula archaeologica.

- Stipčević, Aleksandar (1977). The Illyrians: History and Culture. History and Culture Series. Noyes Press. ISBN 0-8155-5052-9.

- Wilkes, John J. (1992). The Illyrians. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-19807-5.

- Wilkes, J. (2000). "The Danube provinces". In A. Bowman; P. Garnsey; D. Rathbone (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 11, The High Empire, AD 70-192. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 577–603. ISBN 978-0-52126-335-1.