| Battle of Romani | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I | |||||||

8th Light Horse Regiment at Romani | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Anzac Mounted Division's 1st Light Horse Brigade 2nd Light Horse Brigade 52nd (Lowland) Division |

3rd Division Pasha I Ottoman camel Machine gun battalion | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 14,000 | 16,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,130 | 9,200 including 4,000 prisoners | ||||||

Location within Sinai | |||||||

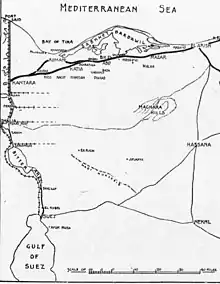

The Battle of Romani was the last ground attack of the Central Powers on the Suez Canal at the beginning of the Sinai and Palestine campaign during the First World War. The battle was fought between 3 and 5 August 1916 near the Egyptian town of Romani and the site of ancient Pelusium on the Sinai Peninsula, 23 miles (37 km) east of the Suez Canal. This victory by the 52nd (Lowland) Division and the Anzac Mounted Division of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) over a joint Ottoman and German force, which had marched across the Sinai, marked the end of the Defence of the Suez Canal campaign, also known as the Offensive zur Eroberung des Suezkanals and the İkinci Kanal Harekâtı, which had begun on 26 January 1915.

This British Empire victory ensured the safety of the Suez Canal from ground attacks and ended the Central Powers' plans to disrupt traffic through the canal by gaining control of the strategically important northern approaches to it. The pursuit by the Anzac Mounted Division, which ended at Bir el Abd on 12 August, began the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. Thereafter the Anzac Mounted Division supported by the Imperial Camel Brigade were on the offensive, pursuing the German and Ottoman army many miles across the Sinai Peninsula, reversing in a most emphatic manner the defeat suffered at Katia three months earlier.[1]

From late April 1916, after a German-led Ottoman force attacked British yeomanry at Katia, British Empire forces in the region at first doubled from one brigade to two and then grew as rapidly as the developing infrastructure could support them. The construction of the railway and a water pipeline soon enabled an infantry division to join the light horse and mounted rifle brigades at Romani. During the heat of summer, regular mounted patrols and reconnaissance were carried out from their base at Romani, while the infantry constructed an extensive series of defensive redoubts. On 19 July the advance of a large German, Austrian and Ottoman force across the northern Sinai was reported. From 20 July until the battle began, the Australian 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades took turns pushing out to battle the advancing hostile column.

During the night of 3–4 August the advancing force, including the German Pasha I formation and the Ottoman 3rd Infantry Division, launched an attack from Katia on Romani. Forward troops quickly became engaged with the screen established by the 1st Light Horse Brigade (Anzac Mounted Division). During fierce fighting before dawn on 4 August, the Australian light horsemen were forced to slowly retire. At daylight their line was reinforced by the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, and about mid morning the 5th Mounted Brigade and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade joined the battle. Together these four brigades of the Anzac Mounted Division managed to contain and direct the determined German and Ottoman forces into deep sand. Here they came within range of the strongly entrenched 52nd (Lowland) Division defending Romani and the railway. Coordinated resistance by all these EEF formations, the deep sand, the heat and thirst prevailed, and the German, Austrian and Ottoman advance was checked. Although the attacking force fought strongly to maintain its positions the next morning, by nightfall they had been pushed back to their starting point at Katia. The retiring force was pursued by the Anzac Mounted Division between 6 and 9 August, during which the Ottomans and Germans forces fought a number of strong rearguard actions against the advancing Australian light horse, British yeomanry and New Zealand mounted rifle brigades. The pursuit ended on 12 August, when the German and Ottoman force abandoned their base at Bir el Abd and retreated to El Arish.

Background

At the beginning of the First World War the Egyptian police controlling the Sinai Peninsula had withdrawn, leaving the area largely unprotected. In February 1915 a German and Ottoman force unsuccessfully attacked the Suez Canal.[2] Minor Ottoman and Bedouin forces operating across the Sinai continued to threaten the canal from March through the Gallipoli campaign until June, when they practically ceased until the autumn.[3] Meanwhile, the German and Ottoman Empires supported an uprising by the Senussi (a political-religious group) on the western frontier of Egypt which began in November 1915.[4]

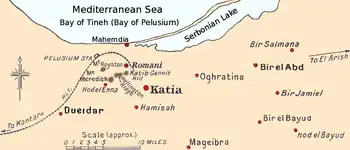

By February 1916, however, there was no apparent sign of any unusual military activity in the Sinai itself, when the British began construction on the first 25-mile (40 km) stretch of 4-foot-8-inch (1.42 m) standard gauge railway and water pipeline from Kantara to Romani and Katia.[5][6] Reconnaissance aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps and seaplanes of the Royal Naval Air Service found only small, scattered Ottoman forces in the Sinai region and no sign of any major concentration of troops in southern Palestine.[7]

By the end of March or early in April, the British presence in the Sinai was growing; 16 miles (26 km) of track, including sidings, had been laid. Between 21 March and 11 April the water sources at Wady Um Muksheib, Moya Harab and Jifjafa along the central Sinai route from southern Palestine were destroyed. In 1915 they had been used by the central group of about 6,000–7,000 Ottoman soldiers who moved across the Sinai Desert to attack the Suez Canal at Ismailia. Without these wells and cisterns, the central route could no longer be used by large forces.[8][9][10]

German General Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein's raiding force retaliated to this growing British presence by attacking the widely dispersed 5th Mounted Brigade on 23 April—Easter Sunday and also St George's Day—when yeomanry were surprised and overwhelmed at Katia and Oghratina east of Romani. The mounted Yeomanry brigade had been sent to guard the water pipeline and railway as they were being extended beyond the protection of the Suez Canal defences into the desert towards Romani.[11][12][13]

In response to this attack, the British Empire presence in the region doubled. The next day the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade and the 2nd Light Horse Brigade which had served dismounted during the Gallipoli campaign,[14] of the Australian Major General Harry Chauvel's Anzac Mounted Division reoccupied the Katia area unopposed.[15]

Prelude

On 24 April—the day after the Katia and Oghratina—Chauvel, commander of the Anzac Mounted Division, was placed in command of all the advanced troops: the 2nd Light Horse Brigade and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigades at Romani and an infantry division; the 52nd (Lowland) at Dueidar.[15][16][17] The infantry moved forward to Romani between 11 May and 4 June 1916.[18]

The building of the railway and pipeline had not been greatly affected by the fighting on 23 April, and by 29 April four trains a day were running regularly to the railhead, manned by No. 276 Railway Company, and the main line to Romani was opened on 19 May. A second standard-gauge railway line from Romani to Mahamdiyah on the Mediterranean coast was completed by 9 June.[16] However, conditions on the ground were extreme; after the middle of May and in particular from mid-June to the end of July, the heat in the Sinai Desert ranged from extreme to fierce, when temperatures could be expected to be in the region of 123 °F (51 °C) in the shade. The terrible heat was not as bad as the Khamsin dust storms that blow once every 50 days for between a few hours and several days; the air is turned into a haze of floating sand particles flung about by a strong, hot southerly wind.[19]

No major ground operations were carried out during these midsummer months, the Ottoman garrisons in the Sinai being scattered and out of reach of the British forces.[20] But constant patrolling and reconnaissance were carried out from Romani to Ogratina, to Bir el Abd and on 16 May to Bir Bayud, 19 miles (31 km) south-east of Romani, on 31 May to Bir Salmana 22 miles (35 km) east north-east of Romani by the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade, when they covered 100 kilometres (62 mi) in 36 hours.[21][22] These patrols concentrated on an area of great strategic importance to large military formations wishing to move across the Sinai along the northern route. Here water was freely available in a large area of oases which extends from Dueidar, 15 miles (24 km) from Kantara on the Suez Canal, along the Darb es Sultani (the old caravan route), to Salmana 52 miles (84 km) away.[23]

Between 10 and 14 June, the last water source on the central route across the Sinai Peninsula was destroyed by the Mukhsheib column. This column, consisting of engineers and units of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, the Bikaner Camel Corps, and the Egyptian Camel Transport Corps drained 5,000,000 US gallons (19,000,000 L; 4,200,000 imp gal) of water from pools and cisterns in the Wadi Mukhsheib and sealed the cisterns. This action effectively narrowed the area in which Ottoman offensives might be expected to the coastal or northern route across the Sinai Peninsula.[22][Note 1]

Ottoman aircraft attacked the Suez Canal twice during May, dropping bombs on Port Said. British aircraft bombed the town and aerodrome at El Arish on 18 May and 18 June, and bombed all the Ottoman camps on a front of 45 miles (72 km) parallel to the canal on 22 May.[20] By the middle of June, the No. 1 Australian Squadron, Australian Flying Corps, had begun active service, with "B" Flight at Suez performing reconnaissance. On 9 July, "A" Flight was stationed at Sherika in Upper Egypt, with "C" Flight based at Kantara.[24]

German and Ottoman force

At the beginning of July, it was estimated there were at least 28,000 Ottoman troops in the Gaza–Beersheba area of southern Palestine, and that just before the battle began at Romani, there were 3,000 troops at Oghratina, not far from Katia, another 6,000 at the forward base of Bir el Abd, east of Oghratina, 2,000 to 3,000 at Bir Bayud to the south-east, and another 2,000 at Bir el Mazar, some 42 miles (68 km) to the east, not far from El Arish.[25][26][27]

Kress von Kressenstein's Fourth Army was made up of the 3rd (Anatolian) Infantry Division's three regiments, the 31st, 32nd and 39th Infantry Regiments, totalling 16,000 men, of whom 11,000 to 11,873 were combatants, Arab ancillary forces; and one regiment of the Camel Corps. Estimates of their arms range from 3,293 to 12,000 rifles, 38 to 56 machine guns, and two to five anti-aircraft gun sections; they also fielded four heavy artillery and mountain gun batteries (30 artillery pieces) and the Pasha I formation. Nearly 5,000 camels and 1,750 horses accompanied the advance.[12][26][28]

The Pasha I formation with a ration strength of about 16,000, consisted of personnel and materiel for a machine gun battalion of eight companies with four guns each with Ottoman drivers, five anti-aircraft groups, the 60th Battalion Heavy Artillery consisting of one battery of two 100 mm guns, one battery of four 150 mm howitzers and two batteries of 210 mm howitzers (two guns in each battery). The officers, NCOs and "leading numbers" of this artillery battalion were German; the remainder were Ottoman Army personnel. In addition Pasha I also included two trench mortar companies, the 300th Flight Detachment, Wireless detachment, three railway companies and two field hospitals. Austria provided two mountain howitzer batteries of six guns each. With the exception of the two 210 mm howitzers, the trench mortars and the railway personnel the remainder of Pasha I took part in the advance to Romani.[28]

The 300th Flight Detachment provided a squadron for aerial reconnaissance, and increased the numbers of aircraft available to support the advance across Sinai. These Pasha I aircraft were faster and more effective than the "hopelessly outclassed" British aircraft and were able to maintain air superiority over the battleground.[29]

It is also possible that the 81st Regiment of the 27th Division advanced to Bir el Abd and took part in the defence of that place.[28]

The objectives of the German, Austrian and Ottoman advance were to capture Romani and to then establish a strongly entrenched position opposite Kantara, from which place their heavy artillery would be within range of the Suez Canal. The attacking force assembled in the southern Ottoman Empire at Shellal, north-west of Beersheba, and departed for the Sinai on 9 July; they reached Bir el Abd and Ogratina ten days later.[26]

British forces

General Sir Archibald Murray, the commander of the British Empire forces in Egypt, formed the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) in March by merging the Force in Egypt, which had protected Egypt since the beginning of the war, with the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force which had fought at Gallipoli. The role of this new force was to both defend the British Protectorate of Egypt and provide reinforcements for the Western Front.[30][31][32] Murray had his headquarters in Cairo to better deal with his multiple responsibilities, although he was at Ismailia during the battle for Romani.[33]

With the occupation of Romani, the area became part the Northern or No. 3 Sector of the Suez Canal defences, which originally stretched along the canal from Ferdan to Port Said. Two further sectors grouped the defence forces along the central and southern sections of the Canal; No. 2, the Central Sector, stretched south from Ferdan to headquarters at Ismailia and on to Kabrit, where the No. 1 or Southern Sector extended from Kabrit to Suez.[34][35]

Murray considered it very unlikely that an attack would occur anywhere other than in the northern sector and therefore was prepared to reduce the troops in Nos 1 and 2 Sectors to a minimum.[36] He decided not to reinforce his four infantry brigades, but to increase the available fire-power at Romani by moving up the 160th and 161st Machine Gun Companies of the 53rd (Welsh) and the 54th (East Anglian) Divisions.[36][37] He also ordered the concentration of a small mobile column made up of the 11th Light Horse, the City of London Yeomanry (less one squadron each) with the 4th, 6th and 9th Companies of the Imperial Camel Brigade in No. 2 Sector. He calculated that the whole of the defensive force, including the camel transport necessary to enable infantry in the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division to advance into the desert, would be fully equipped and the camels assembled by 3 August.[36] Approximately 10,000 Egyptian Camel Transport Corps camels concentrated at Romani prior to the battle.[38][39][Note 2] British monitors in the Mediterranean Sea off Mahamdiyah got into position to shell the assembling Ottoman force, while an armoured train at Kantara was ready to assist the defence of the right flank, and all available aircraft were on standby at Ismailia, Kantara, Port Said and Romani.[40]

Major General H. A. Lawrence commanded No. 3 Section Canal Defences, and as part of those defences, the Romani position was commanded by Lawrence, who had his headquarters at Kantara. Stationed at Kantara were infantry in the 42nd Division, an infantry brigade of the 53rd (Welsh) Division with 36 guns and the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, detached from the Anzac Mounted Division.[40][41][42] Lawrence moved two infantry battalions of the 42nd Division from No. 2 Section Canal defences to Kantara, and sent infantry in the 158th (North Wales) Brigade of the 53rd (Welsh) Division to Romani on 20 July.[43]

The deployments on 3 August on and near the battlefield were as follows:

- at Hill 70, 12 miles (19 km) southwest from Romani, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade (less the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment, but with the 2nd Light Horse Brigade's 5th Light Horse Regiment, temporarily attached), commanded by Edward Chaytor, and the 5th Mounted Brigade, under the direct command of Lawrence, were joined on the railway by infantry in the 126th (East Lancashire) Brigade (42nd Division). Together with the 5th Light Horse Regiment, attached to the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade at Dueidar, to the east of Hill 70, this force was to stop or delay von Kressenstein's attack should he attempt to bypass Romani and advance directly towards the Suez Canal,

- at Hill 40, a little further southwest of Hill 70, infantry from the 125th (Lancashire Fusiliers) Brigade and the 127th (Manchester) Brigade (42nd Division) were also on the railway line at Gilban Station,

- the Mobile Column was based in the Sinai at the end of the El Ferdan railway, while the 3rd Light Horse Brigade was at Ballybunion, also in the Sinai at the end of the Ballah railway.[40][41][42]

- The force at Romani, responsible for its defence when the battle began, consisted of infantry from the British 52nd (Lowland) Division, commanded by Major General W. E. B. Smith, and the Anzac Mounted Division commanded by Chauvel (less the 3rd Light Horse Brigade). The 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades, (less the 5th Light Horse Regiment, but with the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade's Wellington Mounted Rifle Regiment attached) were commanded by Lieutenant Colonels J. B. H Meredith and J. R. Royston respectively.[41]

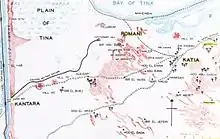

Development of defensive positions

Infantry from the 52nd (Lowland) Division joined the two mounted brigades at Romani between 11 May and 4 June, when the development of the railway made it possible to transport and supply such a large number of soldiers. The infantry occupied a defensive position known as Wellington Ridge, facing a tangle of sand dunes.[18][44] The area favoured defence; sand dunes, stretching about 6 miles (9.7 km) inland, covered an area of 30 square miles (78 km2), including, to the south of Romani, the northern route from El Arish. On the southern and south eastern edges, a series of dunes of shifting sand with narrow sloping lanes led to a tableland of deep soft sand.[45]

The 52nd (Lowland) Division developed a strong defensive position at Romani which had its left flank on the Mediterranean Sea, here a series of redoubts were built running southwards from Mahamdiyah along the line of high sand hills about 7 miles (11 km) to a dune known as Katib Gannit 100 feet (30 m) high. This line of sand hills, which were high enough to see Katia oasis from, marked the eastern edge of an area of very soft and shifting sand beyond which were lower dunes and harder sand where movement by both infantry and mounted forces was considerably easier. Between the shore at the western end of the Bardawil Lagoon and Katib Gannit (the principal tactical point on the eastern slopes of the Romani heights), the infantry constructed a line of 12 redoubts about 750 yards (690 m) apart, with a second series of redoubts covering the Romani railway station and the right of the defensive position which curved like a hook westward, then northward. A total of 18 redoubts were constructed, which when fully garrisoned held from 40 to 170 rifles each, with Lewis guns and an average of two Vickers machine guns allotted to each position; they were well wired on the right side of each of the positions, although there was no wire between the redoubts.[46] This defensive line was supported by artillery.[47][48]

The threat of an Ottoman attack towards the Suez Canal had been considered by Lawrence in consultation with his divisional commanders, and a second defensive area was developed to address their concerns. Their plans took into account the possibility of an Ottoman army at Katia moving to attack Romani or following the old caravan route to assault Hill 70 and Dueidar on their way to the Suez Canal.[49] Any attempt to bypass Romani on the right flank would be open to attack from the garrison, which could send out infantry and mounted troops on the hard ground in the plain to the south-west.[48] The New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade was stationed at Hill 70 at the end of June and the 5th Light Horse Regiment at Dueidar to prevent such an Ottoman force from reaching the Suez Canal.[25][42][50]

Light Horse patrols before the battle

Active patrolling by mounted troops continued throughout the period leading up to the battle, but by early July, there were no indications of any imminent resumption of hostilities. The nearest Ottoman garrison of 2,000 men was at Bir el Mazar 42 miles (68 km) east of Romani, and on 9 July, a patrol found Bir Salmana unoccupied. However, greatly increased aerial activity over the Romani area began about 17 July, when faster and better-climbing German aircraft quickly established superiority over British aircraft. But they could not stop British aircraft from continuing to reconnoitre the country to the east, and on 19 July, a British aircraft, with Brigadier General E. W. C. Chaytor (commander of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade) acting as observer, discovered an Ottoman force of about 2,500 at Bir Bayud. A slightly smaller force was detected at Gameil and another similar sized force was found at Bir el Abd with about 6,000 camels seen at the camps or moving between Bir el Abd and Bir Salmana. The next morning, 3,000 men were found to be entrenched at Mageibra, with an advance depot for supplies and stores at Bir el Abd. A small force was spotted as far forward as the oasis of Oghratina, which by the next day, 21 July, had grown to 2,000 men.[43][51]

On 20 July, the 2nd Light Horse Brigade with two guns mounted on ped-rails of the Ayrshire Battery demonstrated against Oghratina, capturing several prisoners, and beginning a series of patrols which, together with the 1st Light Horse Brigade, they continued until the eve of battle. Every day until 3 August, these two brigades alternated riding out from their base at Romani towards Katia at about 02:00 and bivouacking until dawn, at which time they advanced on a wide front until German or Ottoman fire was provoked. If the enemy position was weak, the light horse pushed forward, and if a counterattack began, the brigade retired slowly, thereafter to return to camp at Romani at nightfall. The following day, the other brigade carried out similar manoeuvres in the direction of Katia and the advancing Ottoman columns, picking up the officers patrols which had been left out during the night to monitor enemy movements.[36][52][53] During this period, one of many clashes occurred on 28 July at Hod Um Ugba, 5 miles (8.0 km) from the British line. Two squadrons of the Wellington Mounted Rifle Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel W. Meldrum, made a bayonet assault, supported by several machine guns and two 18-pounder guns. They drove the Ottomans from the Hod, leaving 16 dead and taking eight prisoners from the Ottoman 31st Infantry Regiment.[54][55]

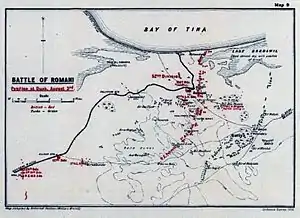

The tactic of continuous forward patrolling was so successful that the advancing force's every move was known to the defenders, but the light horsemen were substantially outnumbered and could not stop the advance. By daylight on 3 August, the German, Austrian and Ottoman force had occupied Katia and were within striking distance of Romani, Dueidar, Hill 70 and the Suez Canal. Their line ran north-east and south-west from the Bardawil Lagoon to east of Katia, with their left flank thrown well forward.[49][56]

Plans

The German and Ottoman objective was not to cross the canal, but to capture Romani and establish a strongly entrenched heavy artillery position opposite Kantara, from which to bombard shipping on the canal. Kress von Kressenstein's plan for the attack on Romani was to bombard the line of defensive redoubts with heavy artillery and employ only weak infantry detachments against them, while his main force launched attacks against the right and rear of the Romani position.[57]

The defenders expected the German and Ottoman attack to be one of containment against their prepared line of defence, and an all-out attack on the right south of Katib Gannit. They also appreciated that such an attack would expose the German and Ottoman left flank. Murray's plan was to firstly delay the attackers and make it very difficult for them to gain ground south of Katib Gannit, and secondly, only when the German and Ottoman force was totally committed, to then disorganise their flank attack with an attack by Section Troops at Hill 70 and Dueidar, with the 3rd Light Horse Brigade and the Mobile Column operating more widely against the flank and rear.[56]

Chauvel had selected a position for the defence of Romani, which stretched for 4 miles (6.4 km) between Katib Gannit and Hod el Enna, with a second fall-back position covering a series of parallel gullies running south-east and north-west giving access to the area of soft sand to the rear of the Romani defences. No visible works were constructed, but together with Chauvel, the commanders of the two light horse brigades, whose task it would be to hold the attackers on this ground until the flank attack could begin, studied the area closely.[58]

Battle on 4 August

Just before midnight on 3/4 August, three columns of the German Pasha I and the 4th Ottoman Army, consisting of about 8,000 men, began their attack on an outpost line held by the 1st Light Horse Brigade three and a half hours after the return of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade from their regular daytime patrol.[59][60][61][Note 3] In addition to the usual officers patrols left out overnight to monitor the enemy's positions, Chauvel decided to leave out for the night the whole of the 1st Light Horse Brigade to hold an outpost line of about 3 miles (4.8 km), covering all entrances to the sandhill plateau which formed the Romani position and which were not protected by infantry posts.[49] A shot or two fired out in the desert to the south-east of their position put the long piquet line of the 1st and 2nd Light Horse Regiment (1st Light Horse Brigade) on alert about midnight, when the 3rd Light Horse Regiment (1st Light Horse Brigade) was called up to the front line. The Austrian, German and Ottoman advance paused after finding the gullies held by the light horsemen, but at about 01:00, a sudden heavy burst of fire along the whole front began the attack of the considerably superior Ottoman and German forces, and by 02:00 they had in many places advanced to within 50 yards (46 m) of the Australian line.[62]

The Ottoman centre and left columns were skilfully led round the open flank of the infantry's entrenchments and on towards the camp and railway.[63] After the moon had set at around 02:30, the Germans and Ottomans made a bayonet charge on Mount Meredith. Although vastly outnumbered, the light horsemen fought an effective delaying action at close quarters, but were forced to relinquish ground slowly and to ultimately evacuate the position by 03:00. Without the benefit of moon light, the light horsemen had fired at the flashes of the enemy's rifles until they were close enough to use bayonets. The 1st Light Horse Brigade was eventually forced back; withdrawing slowly, troop covering troop with steady accurate fire, staving off a general attack with the bayonet to their fall-back position; a large east/west sand dune called Wellington Ridge at the southern edge of the Romani encampment.[63][64][65] During the retirement to Wellington Ridge, the covering squadrons on the left near Katib Gannit were also attacked, as was the squadron on the right, which was taken in the flank and suffered considerable loss, but managed to hold its ground until the position in its rear was occupied. By 03:30, all light horsemen south of Mount Meredith had been forced back to their led horses and had succeeded in disengaging and falling back to their second position. Soon after, an Ottoman machine gun was shooting down on the light horse from Mount Meredith.[62]

Chauvel had relied on the steadiness of the 1st Light Horse Brigade, which he had commanded during the Gallipoli campaign, to hold the line against greatly superior numbers for four hours until dawn, when the general situation could be assessed. Daylight revealed the weakness of the light horse defenders in their second position on Wellington Ridge and that their right was outflanked by strong German and Ottoman forces. At 04:30, the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, commanded by Colonel J. R. Royston, was ordered up by Chauvel from Etmaler and went into action in front of Mount Royston to support and prolong the 1st Light Horse Brigade's right flank by moving up the 6th and 7th Light Horse Regiments into the front line. German, Austrian or Ottoman artillery now opened fire on the infantry defences and camps in the rear; shrapnel inflicted some losses, but the high explosive shells were smothered by the soft sand.[59][65][66] The attackers succeeded in forcing the light horse off Wellington Ridge, which placed them within 700 metres (2,300 ft) of the Romani camp. However, they were unable to press further, as they now became exposed to machine gun and rifle fire from the entrenched infantry of the 52nd (Lowland) Division, and shelling from the horse artillery supporting the light horsemen's determined defence.[67]

Having been held south of Romani, the German and Ottoman force attempted a further outflanking manoeuvre to the west, concentrating 2,000 troops around Mount Royston another sand dune, south-west of Romani.[66] At 05:15, the Ottoman 31st Infantry Regiment pushed forward; then the 32nd and the 39th Infantry Regiments swung around the left and into the British rear.[12] This outflanking movement was steadily progressing along the slopes of Mount Royston and turning the right of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, whose third regiment, the Wellington Mounted Rifles, was now also committed to the front line.[65]

The two brigades of light horse continued to gradually withdraw, pivoting on the extreme right of the infantry position, which covered the left flank and rear of Romani.[68] They were pushed back between Wellington Ridge and Mount Royston, about 2.25 miles (3.62 km) west of the former; the attackers continually forcing back their right flank. Between 05:00 and 06:00, they were compelled to also retire slowly from this ridge, although the 6th and 7th Light Horse Regiment (2nd Light Horse Brigade) still held the western edge. At 06:15, Meredith was ordered to withdraw the 1st Light Horse Brigade behind the line occupied by the 7th Light Horse Regiment north of Etmaler camp. At 07:00, the 6th and 7th Light Horse Regiments retired, squadron by squadron, from the remainder of Wellington Ridge. By about 08:00, German, Austrian and Ottoman fire from the ridge top was directed into the camp only a few hundred yards away, but the Ayrshire and Leicester Batteries quickly stopped this artillery attack.[65]

... their pluck, dash and endurance is beyond all description. I don't mean only the Australians and New Zealanders but the Horse Artillery Territorials as well ... we have fought and won a great battle and my men put up a performance which is beyond all precedent, although worn out with watching and harassing an advancing enemy day and night for a fortnight ... The fighting in the early morning of the 4th was the weirdest thing I ever took on. It was over rolling sand dunes and the enemy who were in thousands, on foot, could see our horses before we could see them in the half light and it was awfully difficult to find cover for them ... Our losses have been heavy, of course, but absolutely nothing in comparison with what has been achieved.

General Chauvel's letter to his wife dated 13 August[69]

It became apparent that the German and Ottoman right column, (31st Infantry Regiment) was attempting a frontal attack on redoubts held by infantry in the 52nd (Lowland) Division. The defenders were able to hold on, but were subjected to severe artillery shelling during the day.[63] Frontal attacks began with heavy German or Austrian fire by their artillery which attempted to breach the infantry defensive line. About 08:00, attacks were being made on Numbers 4 and 5 redoubts which began with heavy artillery fire, but the attacks broke completely when the 31st Ottoman Infantry Regiment were within 150 yards (140 m) of No. 4 redoubt; subsequent attempts were less successful.[70] At about 10:00, Chauvel contacted Brigadier General E. S. Girdwood, commanding 156th Infantry Brigade, requesting his brigade temporarily relieve the light horse brigades until they had watered their horses in preparation for a mounted counterattack. Girdwood refused because his brigade was being held in reserve to support an intended attack eastward by infantry in the 52nd (Lowland) Division.[71]

The light horse had gradually withdrawn back until, at about 11:00, the main German and Ottoman attack was stopped by well directed fire from the Royal Horse Artillery batteries of the Anzac Mounted Division and by light horse rifle and machine gun fire, to which the 52nd (Lowland) Division contributed considerable firepower. The attackers appeared to have exhausted themselves, but they held their ground while Austrian and Ottoman artillery of various calibres, including 5.9" and 10.5 cm guns, fired on the defenders and their camps, and German and Ottoman aircraft severely bombed the defenders. The three columns of the German, Austrian and Ottoman attacking force were brought to a standstill by the coordinated, concerted and determined defence of the 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades and the 52nd (Lowland) Division.[72][Note 4][Note 5]

The Ottoman advance was at a standstill everywhere. After a long night's march, the German and Ottoman troops faced a difficult day under the desert sun without being able to replenish their water and exposed to artillery fire from Romani.[66] At this time, the attacking forces held a line running from the Bardawil (on the Mediterranean coast) southward along the front of the 52nd Infantry Division's entrenchments and then westward through and including the very large sand dunes of Mount Meredith and Mount Royston. But from their position on Mount Royston, the German, Austrian and Ottoman force dominated the camp area of Romani and threatened the railway line.[72]

Reinforcements

Chaytor, commander of the New Zealander Mounted Rifles Brigade, had been advised of the Austrian, German and Ottoman advance against Romani at 02:00. By 05:35, Lawrence at his headquarters of the Northern No. 3 Canal Defences Sector at Kantara, had been informed of the developing attack. He recognised that the main blow was falling on Romani and ordered the 5th Mounted Yeomanry Brigade at Hill 70 to move towards Mount Royston. They were led by a Composite Regiment, which moved off at once, the remainder of the brigade preparing to follow. At 07:25, Lawrence ordered the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade consisting of brigade headquarters and the Canterbury Mounted Rifle Regiment (less the Auckland Mounted Rifles and the attached 5th Light Horse Regiments, 2nd Light Horse Brigade), to move towards Mount Royston via Dueidar and there, pick up the Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment. The Yeomanry and New Zealand brigades had both been stationed at Hill 70, 12 miles (19 km) from Romani, when their orders to move were received. The New Zealanders were to "operate vigorously so as to cut off the enemy, who appears to have got round the right of the Anzac Mounted Division."[70][73][74]

Meanwhile, the 3rd Light Horse Brigade at Ballybunion was directed to move forward to Hill 70 and send one regiment to Dueidar, while the Mobile Column was ordered by GHQ to march towards Mageibra.[70][Note 6]

Mount Royston counterattack

The German, Austrian and Ottoman attack on Mount Royston was checked to the north by the 3rd and 6th Light Horse Regiments (1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades), and under constant bombardment from the horse artillery and the infantry's heavy artillery of the 52nd (Lowland) Division.[75] At 10:00, the front held by the two light horse brigades faced south from a point 700 yards (640 m) northwest of No. 22 Redoubt north of Wellington Ridge to the sand hills north of Mount Royston. As the line had fallen back, the 2nd and 3rd Light Horse Regiments (1st Light Horse Brigade) had come in between the 6th and 7th Light Horse Regiments (2nd Light Horse Brigade); from right to left, the line was now held by the 6th, 3rd, 2nd and 7th Light Horse and the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiments, while 1 mile (1.6 km) north north-west of Mount Royston, "D" Squadron of the Royal Gloucestershire Hussars (a regiment in the 5th Mounted Brigade) held its ground.[71]

The Battle of Romani, which might have been called the second battle of Pelusium ... consisted of the great Turkish attack and our counter stroke.

C. Guy Powles[76]

The plan called for the 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades, the 5th Mounted and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigades to swing round the attackers' left flank and envelop them. The first reinforcements to arrive were the Composite Regiment of the 5th Mounted Brigade; they came up on the flank of their mounted regiment; the Royal Gloucestershire Hussars' "D" Squadron 1,500 yards (1,400 m) west of Mount Royston, which was being attacked by a strong body of Ottoman soldiers. The regiment attacked the Ottomans in enfilade and forced them back.[71]

When the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade's headquarters and the Canterbury Mounted Rifle Regiments were within 1 mile (1.6 km) of Dueidar on the old caravan road, they were ordered to move directly to Canterbury Hill, the last defensible position in front of the railway, east of Pelusium Station, as the strong German and Ottoman attack was threatening to take the railway and Romani. The Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment arrived with its brigade between 11:00 and 11:30 to find the Composite Yeomanry Regiment (5th Mounted Yeomanry Brigade) in contact with the German and Ottoman forces on the south-west side of Mount Royston.[71][73][74]

The 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades first made contact with the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade by heliograph, after which Royston, commanding the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, galloped across to explain the situation. Chaytor then moved the Auckland and Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiments, supported by the Somerset Battery, onto high ground between the right of the light horse and the Yeomanry, which was shortly afterwards joined by the remainder of the 5th Mounted Brigade under the command of Brigadier General Wiggin. At the most critical period of the day's fighting, when the German and Ottoman force of 2,000 dominated the Romani area from Mount Royston, the five mounted brigades (still less the 5th Light Horse Regiment) began their counterattack at 14:00 from the west towards Mount Royston.[72][77][Note 7]

The New Zealand riflemen soon gained a footing on Mount Royston, aided by accurate and rapid shooting from the Somerset Royal Horse Artillery Battery. By 16:00, the attack had proceeded to a point where Chaytor arranged with the 5th Mounted Brigade for a squadron of Royal Gloucestershire Hussars and two troops of the Worcestershire Yeomanry to gallop against the southern spur of Mount Royston. They easily took the spur, the defenders not waiting for the onslaught of the mounted charge. From the crest of the spur, the Gloucestershire squadron shot down the horse teams of an Austrian, German or Ottoman battery of pack guns concentrated in the hollow behind the spur, and the attacking force began to surrender.[78][79][80] The New Zealand Mounted Rifle and 5th Mounted Brigades were supported by leading infantry battalions of the 127th (Manchester) Brigade (which had just arrived) when Ottoman and German soldiers began to surrender en masse. At about 18:00, 500 prisoners, two machine guns and the pack battery were captured, and the outer flank of the attacking force was completely routed.[75][78]

Meanwhile, the inner flank of the German and Ottoman force on Wellington Ridge made a last effort to advance across the ridge, but was driven back by artillery fire. Fresh frontal attacks launched against the main British infantry system of redoubts broke down completely. At 17:05, Major General Smith ordered infantry in the 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade to attack the enemy force on Wellington Ridge on the left of the light horse and in coordination with the counterattack on Mount Royston. An artillery bombardment of Wellington Ridge began at 18:45. Just before 19:00, infantry in the 7th and 8th Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) moved south from behind No. 23 Redoubt; the 8th Scottish Rifles advancing to within 100 yards (91 m) of the crest of Wellington Ridge, before being stopped by heavy rifle fire.[81]

When darkness put an end to the fighting, the 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades established an outpost line and spent the night on the battlefield, while the New Zealand Mounted Rifles and 5th Mounted Brigades withdrew for water and rations at Pelusium Station, where the newly arrived infantry brigades of the 42nd Division were assembling. The 3rd Light Horse Brigade halted at Hill 70, while the Mobile Force had reached the Hod el Bada, 14 miles (23 km) south of Romani station.[82][Note 8] At 19:30, when the New Zealand Mounted Rifle and 5th Mounted Brigades moved from the positions they had won to water and rest at Pelusium, the area was consolidated by infantry in the 127th (Manchester) Brigade, 42nd Division.[79][80] Brigadier General Girdwood ordered infantry in the 7th and 8th Scottish Rifles Battalions to hold their ground on Wellington Ridge until daylight, but to keep close contact with the enemy during the night in the hope of capturing large numbers of tired and disorganised soldiers in the morning.[81] Approximately 1,200 unwounded prisoners were captured during the day and sent to the Pelusium railway station.[83]

Battle on 5 August

Within 24 hours, British commanders were able to concentrate a force of 50,000 men in the Romani area, a three to one advantage. This force included the two infantry divisions—the 52nd and the newly arrived 42nd—four mounted brigades, two of which had been on active duty since 20 July, and two heavily engaged on the front line the day before, and may have included the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, although it was still at Hill 70, and the Mobile Column at Hod el Bada. At this time, command of the 5th Mounted Brigade passed from the Anzac Mounted Division to the infantry division; the 42nd Division, it being suggested that orders required the Anzac Mounted Division to remain in position, and that the 3rd Light Horse Brigade alone was to make a flank attack.[33][84][Note 9]

However, Lawrence's orders for a general advance on 5 August beginning at 04:00 included an advance by the Anzac Mounted Division.[82] His orders read:

- Anzac Mounted Division to press forward with its right on the Hod el Enna and its left in close touch with the infantry from the 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade, 52nd (Lowland) Division, advancing on the line Katib Gannit to Mount Meredith.

- 3rd Light Horse Brigade to move towards Bir el Nuss and attack Hod el Enna from the south keeping in close touch with the Anzac Mounted Division.

- 5th Mounted Brigade, under orders of 42nd Infantry Division to assist the 3rd Light Horse Brigade's link with the Anzac Mounted Division's right.

- 42nd Division to move on the line Canterbury Hill–Mount Royston–Hod el Enna and drive back any opposition to the advance of the mounted troops in close support of Anzac Mounted Division's right flank.

- 52nd (Lowland) Division to move in close support of Anzac Mounted Division's left flank towards Mount Meredith and to prepare for a general advance towards Abu Hamra which was not to be undertaken until further orders from Lawrence at No. 3 Section Headquarters.[85][86][Note 10]

Meanwhile, the German, Austrian and Ottoman force was now spread from Hill 110 almost to Bir en Nuss, but with their left flank unprotected. They could not have been in good shape after fighting all the previous day in intense midsummer heat and having to remain in position overnight, far from water and harassed by British infantry. Their situation was now precarious, as their main attacking force was well past the right of the main British infantry positions; infantry in the 52nd (Lowland) Division was closer to the nearest enemy-controlled water source at Katia than most of the attacking force. Had the British infantry left their trenches promptly and attacked in a south easterly direction, von Kressenstein's force would have had great difficulty escaping.[33][87]

British capture Wellington Ridge

At daybreak, infantry in the 8th Scottish Rifles, 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade, 52nd (Lowland) Division) advanced with the 7th Light Horse and the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiments (2nd Light Horse Brigade), covered by infantry in the 7th Scottish Rifles, 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade, 52nd (Lowland) Division on the left, who had brought 16 machine guns and Lewis guns into a position from which they could sweep the crest and reverse slopes of Wellington Ridge.[88] The Wellington Mounted Rifle Regiment, with the 7th Light Horse Regiment and supported on the left by Scottish Rifles' infantry posts, fixed bayonets and stormed Wellington Ridge. They encountered heavy rifle and machine gun fire, but rushed up the sandy slope and quickly broke through the German and Ottoman front line. After clearing Wellington Ridge, the mounted riflemen, light horsemen and infantrymen pressed forward from ridge to ridge without pause. These troops swept down on a body of about 1,000 to 1,500 Ottoman soldiers, who became demoralised.[89][90][91] As a result of this attack, a white flag was hoisted and by 05:00 the German and Ottoman soldiers who had stubbornly defended their positions on Wellington Ridge, dominating the camps at Romani, were captured.[89][90] A total of 1,500 became prisoners in the neighbourhood of Wellington Ridge; 864 soldiers surrendered to infantry in the 8th Scottish Rifles alone, while others were captured by the light horse and mounted rifles regiments.[88] By 05:30, the main German and Ottoman force was in a disorganised retreat towards Katia, with the 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades and the Ayrshire and Leicestershire batteries not far behind.[89][90] At 06:00, a further 119 men surrendered to the infantry in No. 3 Redoubt; while these prisoners were being dealt with, it became apparent that they were part of a rearguard and that a full retreat was under way.[88] At 06:30, Lawrence ordered Chauvel to take command of all troops and to initiate a vigorous general advance eastwards.[90]

British advance on Ottoman rearguard at Katia

Infantry from the 42nd Division had arrived during the battle the day before by train from Hill 70, Hill 40 and Gilban Station, and along with infantry from the 52nd (Lowland) Division, was ordered to move out in support of the mounted Australian, New Zealand and British Yeomanry brigades.[37][85][92] The 42nd Division was ordered to advance to Hod el Enna; their 127th (Manchester) Brigade marched out at 07:30 and reached Hod el Enna between 09:30 and 10:00, while their 125th (Lancashire Fusiliers) Brigade arrived at 11:15.[37][93] They were supported by the Egyptian Camel Transport Corps, which worked with the Army Service Corps to supply them with drinking water.[94][95][Note 11] In much distress in the scorching midsummer sands, infantry in the 42nd Division marched very slowly and far in the rear. The 52nd (Lowland) Division also experienced difficulties; although Lawrence ordered the division to move at 06:37, the men did not leave their trenches until nearly midday, reaching their objective of Abu Hamra late in the evening. As a result, Kress von Kressenstein was able to extricate most of his troops and heavy guns from the immediate battle area during the day.[90][96][97][Note 12] Although it has been stated that "British reserves hammered" the Germans and Ottomans to a halt on 5 August, it appears one of the infantry divisions was reluctant to leave their defences; neither infantry division were trained in desert warfare and found the sand dunes extremely difficult to negotiate. They could not match the pace and endurance of the well-trained German and Ottoman force and were hampered by water supply problems.[98][99]

At 06:30, when Lawrence ordered Chauvel to take command of all mounted troops (excluding the Mobile Column), the New Zealand Mounted Rifles, the 5th Mounted and the 3rd Light Horse Brigades were somewhat scattered. By 08:30, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade had reached Bir en Nuss; there they found the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, which had been ordered to move first on Hamisah and then left towards Katia to cooperate in a general attack.[Note 13] The advance guard moved to fulfill these orders at 09:00.[100] At 10:30, the general mounted advance began and by midday, was on a line from west of Bir Nagid to south of Katib Gannit; in the centre the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade were approaching the south-west edge of the Katia oasis; on their left the 1st, the 2nd Light Horse, the 5th Mounted Brigades and infantry in the 52nd (Lowland) Division were attacking Abu Hamra, to the north of the old caravan road, while the 3rd Light Horse Brigade was away to the New Zealander's right, south of the old caravan road, attacking German and Ottoman units at Bir el Hamisah.[89][91][93]

Between 12:00 and 13:00, the commanders of the New Zealand Mounted Rifle, 1st and 2nd Light Horse and 5th Mounted Brigades reconnoitred the German, Austrian and Ottoman rearguard position 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Katia. It was decided that the three light horse brigades would advance mounted with the Yeomanry to attack the German and Ottoman right flank.[101] The rearguard force made a very determined stand on a well-prepared line, stretching from Bir El Hamisah to Katia and on to Abu Hamra. Their artillery and machine guns were well placed in the palms fringing the eastern side of a great flat marsh, which stretched right across the front of their position, giving them an excellent field of fire.[96][102]

A general mounted attack commenced at 14:30. By 15:30, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade and the 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades were advancing at the gallop on Katia. When they had reached the edge of the white gypsum, the light horse and mounted rifle brigades formed a line, fixed bayonets, and charged over the exposed country.[103] They galloped in a long line of charging horses, through shell fire and bullets, holding fixed bayonets.[96][102] On the far left, the intensity of fire from the rearguard made it necessary for the 5th Mounted Brigade of sword carrying Yeomanry to send back their horses and advance dismounted. While all the brigades which charged, were eventually forced to attack dismounted also, when the ground became too swampy.[102][Note 14] They were met by well-directed, heavy German, Austrian and Ottoman artillery fire, which completely outgunned the supporting Ayrshire and Somerset Batteries; by sunset, the advance of the British Empire mounted brigades had been stopped.[102] The 9th Light Horse Regiment (3rd Light Horse Brigade) on the extreme right was held up by a determined German and Ottoman rearguard and was unable to work round the right flank of that position. But after galloping to within a few hundred yards of the rearguard's line, they made a dismounted bayonet attack under cover of machine gun fire and the Inverness Battery. As a result, the German and Ottoman force abandoned their position, leaving 425 men and seven machine guns to be captured.[101] But, instead of holding their ground, they drew off, and this withdrawal led to a strong German and Ottoman counterattack falling on the Canterbury Mounted Rifle Regiment.[96]

Darkness finally put an end to the battle. During the night, the Germans, Austrians and Ottomans withdrew back to Oghrantina, while the Anzac Mounted Division watered at Romani, leaving a troop of the Auckland Mounted Rifle Regiment as a listening post on the battlefield.[96][102]

The two-day battle for Romani and the Suez Canal had been won by the British infantry and Australian, British and New Zealand mounted troops. They captured approximately 4,000 German and Ottoman combatants and killed more than 1,200, but the main enemy force was able to escape with all their artillery, except for one captured battery, and retreat back to Oghratina after fighting a successful rearguard action at Katia.[102][104]

Having borne the burden of the long days of patrolling, reconnaissance and minor engagements with the advancing Austrian, German and Ottoman columns prior to the battle, the 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades had alone withstood the attack from midnight on 3/4 August until dawn on 4 August, as well as continuing to fight during the long days of battle. By the end of 5 August, they were completely exhausted; their depleted ranks stumbled back to their bivouac lines at Romani and Etmaler where they were ordered one day's rest.[92][105]

Pursuit begins

Von Kressenstein had prepared successive lines of defence during his advance towards Romani, and despite losing one artillery battery and more than one third of his soldiers, fought a series of effective rearguard actions which slowed the pursuit by British Empire mounted troops and enabled his force to retreat back to El Arish.[106]

During the night of 5/6 August, infantry in the 155th (South Scottish) Brigade and 157th (Highland Light Infantry) Brigade were at Abu Hamra, the 127th (Manchester) Brigade (42nd Division) at Hod el Enna, the 125th (Lancashire Fusiliers) Brigade (42nd Division) on its left in touch with the 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade, (52nd Division) which had its left on Redoubt No. 21. The next morning, infantry in the 42nd Division was ordered to advance eastwards at 04:00 and occupy a line from Bir el Mamluk to Bir Katia, while the 52nd (Lowland) Division was to advance from Abu Hamra and prolong the infantry line of the 42nd Division to the north-east. Although they carried out their orders during their two-day march from Pelusium Station to Katia, infantry in the 127th (Manchester) Brigade lost 800 men, victims to thirst and the sun; other infantry brigades suffered similarly. It became clear that the infantry could not go on, and they ceased to be employed in the advance. Indeed, it was necessary for the Bikanir Camel Corps and Yeomanry detachments, as well as the medical services, to search the desert for those who had been left behind.[37][98][107][108][109]

The Mobile Column in the south, consisting of the Imperial Camel Brigade, the 11th Light Horse, and the mounted City of London Yeomanry Regiments (less two squadrons), advanced from Ferdan and the Ballah railhead to attack the German and Ottoman left flank, working through Bir El Mageibra, Bir El Aweidia and Hod El Bayud.[92][105] They found Mageibra evacuated on 5 August. After camping there for the night, they fought strong hostile forces between Bayud and Mageibra the following day, but could make no impression. Some days later, on 8 August, the Mobile Column did succeed in getting round the Ottoman flank, but was too weak to have any effect and retired to Bir Bayud.[110]

Advance towards Oghratina – 6 August

During the previous night, the German and Ottoman force evacuated Katia and was moving towards Oghratina when Chauvel ordered the Anzac Mounted Division to continue the attack. The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigades and the 5th Mounted Brigade were ordered to capture Oghratina. Despite attempts by these two brigades to turn the enemy flank, they were forced to make a frontal attack on strongly entrenched rearguards in positions which favoured the defenders and which were supported by carefully positioned artillery. Meanwhile, the two infantry divisions moved to garrison Katia and Abu Hamra and Lawrence moved his headquarters forward from Kantara to Romani.[92][97][109][111] The 3rd Light Horse Brigade on the right advanced towards Badieh, but could only make small progress, against positions securely held by German and Ottoman forces.[112]

The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade had moved out at dawn, followed by the 5th Mounted Brigade without ambulance support, as the New Zealand Field Ambulance had not returned from Romani and the 5th Mounted Field Ambulance had not yet arrived. Fortunately, casualties were light, and both ambulances arrived in the evening. The 3rd Light Horse Field Ambulance, had formed a dressing station at Bir Nagid to the south of Romani, treating wounded from 3rd Light Horse Brigade's engagement at Bir el Hamisah, a convoy brought in wounded Ottomans from a hod to the south of Romani, and 150 cases of heat exhaustion from infantry in the 42nd Division were treated during the day.[113]

We are still pursuing but it has been perforce slow as the horses are done and the enemy, when advancing, entrenched himself at various points … which has enabled him to fight a most masterly rearguard action … As I am moving on, I must close

— General Chauvel's letter to his wife dated 13 August[69]

Oghratina entered on 7 August

The same three brigades—one mounted rifle, one light horse and one Yeomanry, with the 10th Light Horse Regiment (3rd Light Horse Brigade) supporting the Yeomanry—moved to attack the German and Ottoman position at Oghratina, but the rearguard position was again found to be too strong.[114][115] Lacking the support of infantry or heavy artillery, the mounted force was too small to capture this strong rearguard position, but the threat from the mounted advance was enough to force the hostile force to evacuate the position.[97][116] During the night, the German and Ottoman forces retreated back to Bir el Abd, where they had been three weeks before, on 20 July, when they established a base with a depot for supplies and stores.[117]

On 7 August the Greater Bairam (a feast day celebrating the end of the Islamic year) coincided with the Egyptian Camel Transport Corps at Romani being ordered to move out with supplies for the advancing troops, but 150 men, most of whom were past the end of their contracts and entitled to be discharged, refused orders to fill their water bottles, draw their rations and saddle up. One man was hit about the head with the butt of a pistol and the dissenters were dispersed into small groups and reassigned to various units in the infantry division; the 52nd (Lowland) Division.[118]

Debabis occupied on 8 August

The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade reached Debabis on 8 August. As the 3rd Light Horse Brigade came up, they passed many dead Ottomans and Yeomanry; one dead Ottoman sniper had a heap of hundreds of rounds of empty cartridge shells beside him. Meanwhile, the Bikanir Camel Corps and a squadron of aircraft continued searching the desert sands for missing men.[97][115][116]

Action of Bir el Abd – 9 to 12 August

Chauvel planned, with Lawrence's approval, to capture the Ottoman rearguard at their forward base of Bir El Abd, 20 miles (32 km) to the east of Romani.[119] The position was strongly held by greatly superior numbers of Germans, Austrians and Ottomans, supported by well-placed artillery, but the garrison was seen burning stores and evacuating camps.[120][121]

Chauvel deployed the Anzac Mounted Division for the advance, with the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade in the centre following the telegraph line. On their right, with a gap of 1 mile (1.6 km), was the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, which was in touch with a small flying column; the Mobile Column of the City of London Yeomanry, 11th Light Horse Regiments and the Imperial Camel Brigade, which was to again attempt to get round the German and Ottoman left flank and cut off their retreat.[Note 15] The advance of the 3rd Light Horse and the New Zealand Mounted Brigades from Oghratina to Bir el Abd was to begin at daylight on 9 August, with the 5th Mounted Brigade forming the reserve. On the left of the New Zealanders, Royston's Column; a composite of the depleted 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades, had gone to Katia to water and had then march through the night to the Hod Hamada 4 miles (6.4 km) north-west of Bir el Abd, where they arrived at 03:00 on 9 August. They were to bivouac for one and a half hours before advancing to a point 2 miles (3.2 km) north-east of Bir el Abd, to cooperate with the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade's attack on the rearguard position at 06:30.[69][92][122] Since the attack, supported by only four horse artillery batteries, was on a prepared position held in superior strength, strong in machine guns, and covered by double the number of guns, including heavy howitzers, it was something of a gamble. The attacking force's only advantage was its mobility.[122]

Attack on 9 August

The 3rd Light Horse Brigade set out to find and turn the German and Ottoman left, while at 04:00 the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade headed directly towards Bir el Abd along the old caravan route. By 05:00, they had driven in enemy outposts and reached high ground overlooking Bir el Abd. Royston's Column moved off at 05:00 with the intention of enveloping the Ottoman right, while the New Zealanders attacked in the centre; the four brigades covering a front of 5 miles (8.0 km).[92][123]

The forward troops of the German and Ottoman rearguard, which held a front of about 10 miles (16 km), were driven back to Bir el Abd by the New Zealanders. At this time, the attackers appeared likely to succeed, as they had firmly established themselves across the telegraph line and the old caravan road, supported by the Somerset and Leicester batteries.[69][92][120] But the German, Austrian and Ottoman rearguard quickly realised how thin the attacking line was, and at 09:00 advanced out of their trenches to counterattack. This aggressive move was only checked by artillery fire from the Somerset Battery effectively combined with fire from machine guns. The subsequent fire fight made it extremely difficult for the mounted riflemen to maintain their position, and on the flanks the light horse were also held up. The German and Ottoman infantry renewed their attack towards a gap between the New Zealanders and the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, but the 5th Light Horse Regiment covered the gap, and the German and Ottoman advance was halted.[123]

Chauvel ordered the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, which had been unable to turn the German and Ottoman flank, to move towards the New Zealanders who renewed their efforts, but they only succeeded in exposing their flanks, as the Australians were unable to conform to their forward movement. By 10:30, all progress had stopped.[123] The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade continued to hold on in the centre, while both flanks were bent back by pressure from the strong German and Ottoman force. The result was that the New Zealanders ended up holding a very exposed salient line on the forward slopes of the hills overlooking the Hod. Fresh German or Ottoman reinforcements from El Arish, then launched a fierce counterattack on a front of about 2.5 miles (4.0 km), on the centre. This fell on the Canterbury and Auckland Regiments and a squadron of Warwickshire Yeomanry of the 5th Mounted Brigade under Chaytor's command. The New Zealanders were supported by machine guns; one section, attached to the Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiment, fired all their guns directly on the advancing soldiers, stopping them when they were within 100 yards (91 m) of the New Zealand position.[121]

By midday, the advance had been completely held up by determined counterattacks supported by fresh German or Ottoman troops from El Arish. Even more than at Katia on 5 August, these soldiers were more numerous, ready, full of fight and more strongly supported by well-placed Austrian and Ottoman guns delivering both heavy and accurate fire.[69][92][120] At this time, the rearguard launched another heavy counterattack with two columns of 5,000 and 6,000 German and Ottoman soldiers against the Canterbury and Auckland Regiments and the squadron of the Warwickshire Yeomanry.[92][123] By 14:00, the attack had extended to the mounted force's left flank where the Ayrshire Battery with Royston's Column was badly cut up by this fire, losing 39 horses killed and making it extremely difficulty to move the guns. They were forced to retire nearly 1 mile (1.6 km) and the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, after advancing well up on the right flank, was also forced to give ground by the accuracy of enemy shellfire.[69][121][124]

A further withdrawal by the 3rd Light Horse Brigade made the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade's position critical and at 17:30, Chauvel gave orders for a general retirement. Disengagement proved to be a challenge; it was only the tenacity of the New Zealanders and nightfall which saved them from certain capture. At the last, the Machine Gun Squadron had all its guns in line, some of them firing at a range of 100 yards (91 m); they were supported by squadrons of the 5th Mounted Brigade, which together, successfully covered the New Zealanders' withdrawal.[121][125]

After this day of fierce fighting, which has been described as the hardest-fought action of the whole Sinai campaign, the Anzac Mounted Division's advance was effectively stopped. Chauvel ordered the division to return to water at Oghratina, despite Lawrence's wish for them to bivouac close to Bir el Abd but Chauvel concluded that his force was in no condition to remain within reach of this strong and aggressive enemy force.[69][120] Further, the Anzac Mounted Division had lost a significant proportion of their strength; over 300 casualties, including eight officers and 65 other ranks killed.[125]

Planned attack for 12 August

At daylight on 10 August, strong patrols went forward and remained in touch with the force at Bir el Abd throughout the day, but without fresh troops, an attack in force could not be made.[126]

No serious fighting took place on 11 August, but von Kressenstein's force at Bir el Abd was watched and harassed, and plans were made for an attack on 12 August. The advance of the Anzac Mounted Division began at daylight, but soon afterwards, forward patrols reported that the garrison at Bir el Abd was retiring. The mounted force followed the Austrians, Germans and Ottomans as far as Salmana, where another rearguard action delayed the mounted force, as the enemy withdrawal continued back to El Arish.[69][126]

The Anzac Mounted Division's lines of communication were now fully extended, and the difficulties of supplying the mounted troops from Romani made it impossible for the British Empire mounted force to consider any further advance at that time. Arrangements were made to hold and garrison the country decisively won by this series of indecisive engagements, from Katia eastwards to Bir El Abd.[126]

Von Kressenstein succeeded in withdrawing his battered force from a potentially fatal situation; both his advance to Romani and the withdrawal were remarkable achievements of planning, leadership, staff work and endurance.[127]

Casualties

According to the Australian official medical history, the total British Empire casualties were:

| Killed | Died of wounds | Wounded[128] | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| British | 79 | 27 | 259 | 365 |

| Australian | 104 | 32 | 487 | 623 |

| New Zealand | 39 | 12 | 163 | 214 |

| Total | 222 | 71 | 909 | 1202 |

Other sources put the total killed at 202, with all casualties at 1,130, of whom 900 were from the Anzac Mounted Division.[98][127][129]

Ottoman Army casualties have been estimated to have been 9,000; 1,250 were buried after the battle and 4,000 were taken prisoner.[98][127]

Casualties were cared for by medical officers, stretcher bearers, camel drivers and sand-cart drivers who worked tirelessly, often in the firing line, covering enormous distances in difficult conditions and doing all they could to relieve the suffering of the wounded. The casualties were transported on cacolets on camels or in sand-carts back to the field ambulances, as the heavy sand made it impossible to use motor- or horse-drawn ambulances. Between 4 and 9 August, the Anzac Mounted Division's five field ambulances brought in 1,314 patients, including 180 enemy wounded.[128][130]

The evacuation by train from Romani was carried out in a manner which caused much suffering and shock to the wounded. It was not effected till the night of 6 August—the transport of prisoners of war being given precedence over that of the wounded—and only open trucks without straw were available. The military exigencies necessitated shunting and much delay, so that five hours were occupied on the journey of twenty-five miles. It seemed a cruel shame to shunt a train full of wounded in open trucks, but it had to be done. Every bump in our springless train was extremely painful.

— Extract from the diary of a yeomanry medical officer who was severely wounded at Katia on 5 August.[120]

In the absence of orders coordinating evacuation from the field ambulances, the assistant director of Medical Services (ADMS) made their own arrangements.[131] The ADMS, Anzac Mounted Division arranged with his counterparts in the two infantry divisions to set up a clearing station at the railhead 4 miles (6.4 km) beyond Romani. This station was formed from medical units of the Anzac Mounted, the 42nd and the 52nd (Lowland) Divisions. With no orders from No. 3 Section Headquarters as to the method of evacuation of casualties of the three divisions, prisoners of war were transported back to Kantara by train before the wounded, generating amongst all ranks a feeling of resentment and distrust towards the higher command which lasted for a long time.[132][133]

Aftermath

The Battle of Romani was the first large-scale mounted and infantry victory by the British Empire in the First World War.[134] It occurred at a time when the Allied nations had experienced nothing but defeat, in France, at Salonika and at the capitulation of Kut in Mesopotamia. The battle has been widely acknowledged as a strategic victory and a turning point in the campaign to restore Egypt's territorial integrity and security, and marked the end of the land campaign against the Suez Canal.[135][136]

Romani was the first decisive victory attained by British Land Forces and changed the whole face of the campaign in that theatre, wresting as it did from the enemy, the initiative which he never again obtained. It also made the clearing of his troops from Egyptian territory a feasible proposition.

— General Chauvel[137]

This series of successful British infantry and mounted operations resulted in the complete defeat of the 16,000 to 18,000 strong German, Austrian and Ottoman force, about half of whom were killed or wounded, and nearly 4,000 taken prisoner. Also captured were a mountain gun battery of four heavy guns, nine machine guns, a complete camel-pack machine gun company, 2,300 rifles and a million rounds of ammunition, two complete field hospitals with all instruments, fittings and drugs, while a great quantity of stores in the supply depot at Bir el Abd was destroyed. All the captured arms and equipment were made in Germany, and the camel-pack machine gun company's equipment had been especially designed for desert warfare. Many of the rifles were of the latest pattern and made of rustless steel. Murray estimated the total German and Ottoman casualties at about 9,000, while a German estimate put the loss at one third of the force (5,500 to 6,000), which seems low considering the number of prisoners.[98][129][138]

The tactics employed by the Anzac Mounted Division were to prove effective throughout the coming campaigns in the Sinai and in the Levant (also known at the time as Palestine). The key to the mounted rifles and light horse's approach was to quickly move onto tactical ground and then to effectively operate as infantry once dismounted.[139] In defence, the artillery and machine guns wrought havoc on enemy attacks, and during the mounted advance, they covered and supported the British Empire mounted force.[130]

This battle was fought under extreme conditions in the Sinai desert in midsummer heat over many days, causing much suffering to man and beast and demanding tenacity and endurance on the part of all who took part.[130]

The battle of Romani marked the end of the German and Ottoman campaign against the Suez Canal; the offensive had passed decisively into the hands of the British Empire force led by the Anzac Mounted Division. After the battle, von Kressenstein's force was pushed back across the Sinai Peninsula, to be beaten at the Battle of Magdhaba in December 1916 and back to the border of Ottoman Empire-controlled Palestine to be defeated at the Battle of Rafa in January 1917, which effectively secured the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula. This successful, seven-month-long British Empire campaign, begun at Romani in August, ended at the First Battle of Gaza in March 1917.[140]

Some criticisms

The Battle of Romani has, however, been surrounded with controversy and criticism. It has been suggested that, like the attack on the Suez Canal in 1915, it was merely a raid to disrupt maritime traffic rather than a determined attempt to gain control of the canal. That the Ottoman Empire's intention was to strongly occupy Romani and Kantara is supported by preparations in the southern territory of Palestine adjacent to, and extending into, the Sinai. These included extending the Palestine railway system to Wadi El Arish, with a good motor road beside the railway. Cisterns and other works were constructed along this route to store water and at Wadi El Arish, enormous rock cut reservoirs were under construction in December 1916 when the Anzac Mounted Division reached that place just before the Battle of Magdhaba.[141]

The battle should either have been Murray's or, if it had to be Lawrence's, he should have placed all the troops available for it at Lawrence's disposal, the moment the enemy arrived in strength at Oghratina.

General Chauvel[137]

Murray, Lawrence and Chauvel have all been criticised for letting von Kressenstein's force escape.[127] Further, it has been asserted that the tactics of the mounted troops actually helped the enemy withdrawal by concentrating on direct assaults rather than flank attacks.[142] The official British historian acknowledges the disappointment caused by the successful retirement of the German, Austrian and Ottoman force but he also notes the quality of the successive rearguard positions constructed during the advance, and the strength, determination and endurance of the enemy.[129] The strength of the rearguards was clearly demonstrated at Bir el Abd on 9 August, when the mounted force attempted to outflank the large entrenched force. They failed because they were greatly outnumbered.[96][143] Indeed, if the Anzac Mounted Division had succeeded in getting round the flank without infantry support, they would have been faced with vastly superior forces and could have been annihilated.[144]

It has been suggested that an opportunity was lost on 5 August to encircle and capture the invading Austrian, German and Ottoman force when it was allowed to withdraw to Katia. The infantry's difficulties regarding the supply of water and camel transport combined with their lack of desert training, together with Lawrence's confusing orders for infantry in the 52nd (Lowland) Division to move south and east, stopped them from promptly advancing to cut off the retreating force in the early hours of the second day's battle.[85][140] General Lawrence was criticised for taking a grave and unnecessary risk by relying on just one entrenched infantry division and two light horse brigades to defend Romani. That the strong enemy attack on the 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades during the first night's battle pushed them so far back that the planned flanking attack by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade became almost a frontal attack. Lawrence was also faulted for remaining at his headquarters at Kantara, which was considered to be too far from the battlefield, and that this contributed to his loss of control of the battle during the first day, when the telephone line was cut and he was out of contact with Romani. Lawrence was also criticised for not going forward to supervise the execution of his orders on 5 August, when there was a failure to coordinate the movements of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade and the Mobile Column.[98][140][145]

Chauvel responded by pointing out that the criticisms of the battle were in danger of obscuring the significance of the victory.[127]

Awards

Murray lavished praise on the Anzac Mounted Division in cables to the Governors General of Australia and New Zealand and in his official despatch and in letters to Robertson, writing:

Every day they show what an indispensable part of my forces they are ... I cannot speak too highly of the gallantry, steadfastness and untiring energy shown by this fine division throughout the operations ... These Anzac troops are the keystone of the defence of Egypt.[146]

But he failed to ensure the fighting qualities of these soldiers earned them a proportionate share of recognition and honours. Further, despite claims that Chauvel alone had a clear view of the battle, that his coolness and skill were crucial in gaining the victory, his name was omitted from the long list of honours published on New Year's Day 1917. Murray did offer Chauvel a lesser award (a Distinguished Service Order) for Romani which he declined.[147][148]

On reading Murray's description in his official despatch covering the battle, and reprinted in a Paris edition of the 'Daily Mail', Chauvel wrote to his wife on 3 December 1916,

I am afraid my men will be very angry when they see it. I cannot understand why the old man cannot do justice to those to whom he owed so much and the whole thing is so absolutely inconsistent with what he had already cabled.[149]