| Battle of San Jacinto | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Texas Revolution | |||||||

.jpg.webp) The Battle of San Jacinto – 1895 painting by Henry Arthur McArdle (1836–1908)[1] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Centralist Republic of Mexico | Republic of Texas | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

approximate location of the battle Location within Texas | |||||||

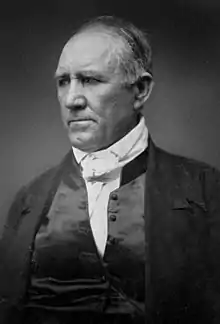

The Battle of San Jacinto (Spanish: Batalla de San Jacinto), fought on April 21, 1836, in present-day La Porte and Deer Park, Texas, was the final and decisive battle of the Texas Revolution. Led by General Samuel Houston, the Texan Army engaged and defeated General Antonio López de Santa Anna's Mexican army in a fight that lasted just 18 minutes. A detailed, first-hand account of the battle was written by General Houston from the headquarters of the Texan Army in San Jacinto on April 25, 1836.[3] Numerous secondary analyses and interpretations have followed.

General Santa Anna, the president of Mexico, and General Martín Perfecto de Cos both escaped during the battle. Santa Anna was captured the next day on April 22 and Cos on April 24. After being held for about three weeks as a prisoner of war, Santa Anna signed the peace treaty that dictated that the Mexican army leave the region, paving the way for the Republic of Texas to become an independent country. These treaties did not necessarily recognize Texas as a sovereign nation but stipulated that Santa Anna was to lobby for such recognition in Mexico City. Sam Houston became a national celebrity, and the Texans' rallying cries from events of the war, "Remember the Alamo" and "Remember Goliad", became etched into Texan history and legend.

Background: December 1832 – March 1836

Mexican constitution overturned

General Antonio López de Santa Anna was a proponent of governmental federalism when he helped oust Mexican President Anastasio Bustamante in December 1832. Upon his election as president in April 1833,[4] Santa Anna switched his political ideology and began implementing centralist policies that increased the authoritarian powers of his office.[5] His abrogation of the Constitution of 1824, correlating with his abolishing local-level authority over Mexico's state of Coahuila y Tejas (Coahuila and Texas), became a flashpoint in the growing tensions between the central government and its Tejano and Anglo citizens in Texas. While in Mexico City awaiting a meeting with Santa Anna, Texian empresario Stephen F. Austin wrote to the ayuntamiento (city council) of Béxar (now San Antonio) urging a break-away state. In response, the Mexican government kept him imprisoned for most of 1834.[6][7]

Colonel Juan Almonte was appointed director of colonization in Texas,[8] ostensibly to ease relations with the colonists and mitigate their anxieties about Austin's imprisonment.[9] He delivered promises of self-governance and conveyed regrets that the Mexican Congress deemed it constitutionally impossible for Texas to be a separate state. Behind the rhetoric, his covert mission was to identify the local power brokers, obstruct any plans for rebellion, and supply the Mexican government with data that would be of use in a military conflict. For nine months in 1834, under the guise of serving as a government liaison, Almonte traveled through Texas and compiled an all-encompassing intelligence report on the population and its environs, including an assessment of their resources and defense capabilities.[10]

Cos is appointed military governor of Texas

In consolidating his power base, Santa Anna installed General Martín Perfecto de Cos as the governing military authority over Texas in 1835.[11][12] Cos established headquarters in San Antonio on October 9, triggering what became known as the Siege of Béxar.[13] After two months of trying to repel the Texian forces, Cos raised a white flag on December 9 and signed surrender terms two days later.[14] The surrender of Cos effectively removed the occupying Mexican army from Texas. Many believed the war was over, and volunteers began returning home.[15]

In compliance with orders from Santa Anna, Mexico's Minister of War José María Tornel issued his December 30 "Circular No. 5", often referred to as the Tornel Decree, aimed at dealing with United States intervention in the uprising in Texas. It declared that foreigners who entered Mexico for the purpose of joining the rebellion were to be treated as "pirates", to be put to death if captured. In adding "since they are not subjects of any nation at war with the republic nor do they militate under any recognized flag," Tornel avoided declaring war on the United States.[16][17]

Santa Anna takes the Alamo

The Mexican Army of Operations numbered 6,019 soldiers[18] and was spread out over 300 miles (480 km) on its march to Béxar. General Joaquín Ramírez y Sesma was put in command of the Vanguard of the Advance that crossed into Texas.[19] Santa Anna and his aide-de-camp Almonte[20] forded the Rio Grande at Guerrero, Coahuila on February 16, 1836,[21] with General José de Urrea and 500 more troops following the next day at Matamoros.[22] Béxar was captured on February 23, and when the assault commenced, attempts at negotiation for surrender were initiated from inside the fortress. William B. Travis, the garrison commander, sent Albert Martin to request a meeting with Almonte, who replied that he did not have the authority to speak for Santa Anna.[23] Colonel James Bowie dispatched Green B. Jameson with a letter, translated into Spanish by Juan Seguín, requesting a meeting with Santa Anna, who immediately refused. Santa Anna did, however, extend an offer of amnesty to Tejanos inside the fortress. Alamo non-combatant survivor Enrique Esparza said that most Tejanos left when Bowie advised them to take the offer.[24]

Cos, in violation of his surrender terms, forded into Texas at Guerrero on February 26 to join with the main army at Béxar.[25] Urrea proceeded to secure the Gulf Coast and was victorious in two skirmishes with Texian detachments serving under Colonel James Fannin at Goliad. On February 27 a foraging detachment under Frank W. Johnson at San Patricio was attacked by Urrea. Sixteen were killed and twenty-one taken prisoner, but Johnson and four others escaped.[26][27] Urrea sent a company in search of James Grant and Plácido Benavides who were leading a company of Anglos and Tejanos towards an invasion of Matamoros. The Mexicans ambushed a group of Texians, killing Grant and most of the company. Benavides and 4 others escaped, and 6 were taken prisoner.[28][29]

The Convention of 1836 met at Washington-on-the-Brazos on March 1.[30] The following day, Sam Houston's 42nd birthday, the 59 delegates signed the Texas Declaration of Independence and chose an ad interim government.[30][31] When news of the declaration reached Goliad, Benavides informed Fannin that in spite of his opposition to Santa Anna, he was still loyal to Mexico and did not wish to help Texas break away. Fannin discharged him from his duties and sent him home.[32] On March 4, Houston's military authority was expanded to include "the land forces of the Texian army both Regular, Volunteer, and Militia."[33]

At 5 a.m. on March 6, the Mexican troops launched their final assault on the Alamo. After a vicious 90 minute battle, with immense losses to the Mexican forces, the guns fell silent; the Alamo had fallen.[34] Survivors Susanna Dickinson, her daughter Angelina, Travis' slave Joe, and Almonte's cook Ben were spared by Santa Anna and sent to Gonzales, where Texian volunteers had been assembling.[35]

Texian retreat: the Runaway Scrape

The same day that Mexican troops departed Béxar, Houston arrived in Gonzales and informed the 374 volunteers (some without weapons) gathered there that Texas was now an independent republic.[36] Just after 11 p.m. on March 13, Susanna Dickinson and Joe brought news that the Alamo garrison had been defeated and the Mexican army was marching towards Texian settlements. A hastily convened council of war voted to evacuate the area and retreat. The evacuation commenced at midnight and happened so quickly that many Texian scouts were unaware the army had moved on. Everything that could not be carried was burned, and the army's only two cannon were thrown into the Guadalupe River.[37] When Ramírez y Sesma reached Gonzales the morning of March 14, he found the buildings still smoldering.[38]

Most citizens fled on foot, many carrying their small children. A cavalry company led by Seguín and Salvador Flores were assigned as rear guard to evacuate the more isolated ranches and protect the civilians from attacks by Mexican troops or Indians.[39] The further the army retreated, the more civilians joined the flight.[40] For both armies and the civilians, the pace was slow; torrential rains had flooded the rivers and turned the roads into mud pits.[41]

As news of the Alamo's fall spread, volunteer ranks swelled, reaching about 1,400 men by March 19.[41] Houston learned of Fannin's surrender on March 20 and realized his army was the last hope for an independent Texas. Concerned that his ill-trained and ill-disciplined force would be good for only one battle, and aware that his men could easily be outflanked by Urrea's forces, Houston continued to avoid engagement, to the immense displeasure of his troops.[42] By March 28, the Texian army had retreated 120 miles (190 km) across the Navidad and Colorado Rivers.[43] Many troops deserted; those who remained grumbled that their commander was a coward.[42]

On March 31, Houston paused his men at Groce's Landing on the Brazos River.[Note 1] Two companies that refused to retreat further were assigned to guard the crossing.[44] For the next two weeks, the Texians rested, recovered from illness, and, for the first time, began practicing military drills. While there, two cannon, known as the Twin Sisters, arrived from Cincinnati, Ohio.[45] Interim Secretary of War Thomas Rusk joined the camp, with orders from President David G. Burnet to replace Houston if he refused to fight. Houston quickly persuaded Rusk that his plans were sound.[45] Secretary of State Samuel P. Carson advised Houston to continue retreating all the way to the Sabine River, where more volunteers would likely flock from the United States and allow the army to counterattack.[Note 2][46] Unhappy with everyone involved, Burnet wrote to Houston: "The enemy are laughing you to scorn. You must fight them. You must retreat no further. The country expects you to fight. The salvation of the country depends on your doing so."[45] Complaints within the camp became so strong that Houston posted notices that anyone attempting to usurp his position would be court-martialed and shot.[47]

Santa Anna and a smaller force had remained in Béxar. After receiving word that acting President Miguel Barragán had died, Santa Anna seriously considered returning to Mexico City to solidify his position. Fear that Urrea's victories would position him as a political rival convinced Santa Anna to remain in Texas to personally oversee the final phase of the campaign.[48] He left on March 29 to join Ramírez y Sesma, leaving only a small force to hold Béxar.[49] At dawn on April 7, their combined force marched into San Felipe and captured a Texian soldier, who informed Santa Anna that the Texians planned to retreat further if the Mexican army crossed the Brazos River.[50] Unable to cross the Brazos because of the small company of Texians barricaded at the river crossing, on April 14 a frustrated Santa Anna led a force of about 700 troops to capture the interim Texas government.[51][52] Government officials fled mere hours before Mexican troops arrived in Harrisburgh (now Harrisburg, Houston) and Santa Anna sent Almonte with 50 cavalry to intercept them in New Washington. Almonte arrived just as Burnet shoved off in a rowboat, bound for Galveston Island. Although the boat was still within range of their weapons, Almonte ordered his men to hold their fire so as not to endanger Burnet's family.[53]

At this point, Santa Anna believed the rebellion was in its final death throes. The Texian government had been forced off the mainland, with no way to communicate with its army, which had shown no interest in fighting. He determined to block the Texian army's retreat and put a decisive end to the war.[53] Almonte's scouts incorrectly reported that Houston's army was going to Lynchburg Crossing on Buffalo Bayou, in preparation for joining the government in Galveston, so Santa Anna ordered Harrisburgh burned and pressed on towards Lynchburg.[53]

The Texian army had resumed their march eastward. On April 16, they came to a crossroads; one road led north towards Nacogdoches, the other went to Harrisburgh. Without orders from Houston and with no discussion amongst themselves, the troops in the lead took the road to Harrisburgh. They arrived on April 18, not long after the Mexican army's departure.[54] That same day, Deaf Smith and Henry Karnes captured a Mexican courier carrying intelligence on the locations and future plans of all of the Mexican troops in Texas. Realizing that Santa Anna had only a small force and was not far away, Houston gave a rousing speech to his men, exhorting them to "Remember the Alamo" and "Remember Goliad". His army then raced towards Lynchburg.[55] Out of concern that his men might not differentiate between Mexican soldiers and the Tejanos in Seguín's company, Houston originally ordered Seguín and his men to remain in Harrisburgh to guard those who were too ill to travel quickly. After loud protests from Seguín and Antonio Menchaca, the order was rescinded, provided the Tejanos wear playing cards in their hats to identify them as Texian soldiers.[56]

Battle

The area along Buffalo Bayou had many thick oak groves, separated by marshes. This type of terrain was familiar to the Texians and quite alien to the Mexican soldiers.[57] Houston's army, comprising around 800 men, reached Lynch's Ferry mid-morning on April 20; Santa Anna's 700-man force arrived a few hours later. The Texians made camp in a wooded area along the bank of Buffalo Bayou; while the location provided good cover and helped hide their full strength, it also left the Texians no room for retreat.[58][59] Over the protests of several of his officers, Santa Anna chose to make camp in a vulnerable location, a plain near the San Jacinto River, bordered by woods on one side, marsh and lake on another.[57][60] The two camps were approximately 500 yards (460 m) apart, separated by a grassy area with a slight rise in the middle.[61] Colonel Pedro Delgado later wrote that "the camping ground of His Excellency's selection was in all respects, against military rules. Any youngster would have done better."[62]

Over the next several hours, two brief skirmishes occurred. Using the Twin Sisters, Texians won the first, forcing a small group of dragoons and the Mexican artillery to withdraw.[57][63] Mexican dragoons then forced the Texian cavalry to withdraw. In the melee, Rusk, on foot to reload his rifle, was almost captured by Mexican soldiers but was rescued by newly arrived Texian volunteer Mirabeau B. Lamar.[63] Over Houston's objections, many infantrymen rushed onto the field. As the Texian cavalry fell back, Lamar remained behind to rescue another Texian who had been thrown from his horse; Mexican officers "reportedly applauded" his bravery.[64] Houston was irate that the infantry had disobeyed his orders and given Santa Anna a better estimate of their strength; the men were equally upset that Houston had not allowed a full battle.[65]

Throughout the night, Mexican troops worked to fortify their camp, creating breastworks out of everything they could find, including saddles and brush.[66] At 9 a.m. on April 21, Cos arrived with 540 reinforcements, bringing the Mexican force to approximately 1,200–1,500 men which outnumbered the Texian aggregate forces of approximately 800 men (official count entering battle was reported at 783).[67] General Cos' men were mostly raw recruits rather than experienced soldiers, and they had marched steadily for more than 24 hours with no rest and no food.[68] As the morning wore on with no Texian attack, Mexican officers lowered their guard. By afternoon, Santa Anna had permitted Cos' men to sleep; his tired troops also took advantage of the time to rest, eat, and bathe.[69]

Not long after Cos arrived with reinforcements, General Houston ordered Smith to destroy Vince's Bridge (located about 8 miles from the Texian encampment) to block the only road out of the Brazos and, thereby, prevent any possibility of escape by Santa Anna.[70] Houston describes how he arrayed the Texian forces in preparation of battle: "Colonel Edward Burleson was assigned the center. The second regiment, under the command of Colonel Sydney Sherman (sic), formed the left-wing of the army. The artillery, under the special command of Col. Geo. W. Hackley, inspector general, was placed on the right of the first regiment, and four companies under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Millard, sustained the artillery on the right, and our cavalry, sixty-one in number and commanded by Colonel Mirabeau B. Lamar...placed on our extreme right, composed our line." [71]

'_(11109994645).jpg.webp)

The Texian cavalry was first dispatched to the Mexican forces' far left, and the artillery advanced through the tall grass to within 200 yards of the Mexican breastworks.[71] The Texian Twin Sisters fired at 4:30, beginning the battle.[72] After a single volley, Texians broke ranks and swarmed over the Mexican breastworks, yelling "Remember the Alamo! Remember La Bahia (Goliad)!", to engage in hand-to-hand combat. Mexican soldiers were taken by surprise. Santa Anna, Castrillón, and Almonte yelled often conflicting orders, attempting to organize their men into some form of defense.[73] The Texian infantry forces advanced without halt until they had possession of the woodland and the Mexican breastwork; the right-wing of Burleson's and the left-wing of Millard's forces took possession of the breastwork.[71] Within 18 minutes, Mexican soldiers abandoned their campsite and fled for their lives.[74] The killing lasted for hours.[75]

Many Mexican soldiers retreated through the marsh to Peggy Lake.[Note 3] Texian riflemen stationed themselves on the banks and shot at anything that moved. Many Texian officers, including Houston and Rusk, attempted to stop the slaughter, but they were unable to gain control of the men, incensed and vengeful for the massacres at the Alamo and Goliad, while frightened Mexican infantry yelled "Me no Alamo!" and begged for mercy to no avail.[76] In what historian Davis calls "one of the most one-sided victories in history",[77] 650 Mexican soldiers were killed, 208 wounded, and 300 captured.[78] Eleven Texians were killed and mortally wounded, with 30 others, including Houston, wounded.[79]

Although Santa Anna's troops had been thoroughly vanquished, they did not represent the bulk of the Mexican army in Texas. An additional 4,000 troops remained under the commands of Urrea and General Vicente Filisola.[80] Texians had won the battle because of mistakes made by Santa Anna, and Houston was well aware that his troops would have little hope of repeating their victory against Urrea or Filisola.[81] As darkness fell, a large group of prisoners was led into camp. Houston initially mistook the group for Mexican reinforcements and reportedly shouted out that all was lost.[82]

Mexican retreat

Santa Anna had escaped towards Vince's Bridge.[83] Finding the bridge destroyed, he hid in the marsh and was captured the following day, wearing the uniform jacket of a private. This subterfuge was uncovered when other Mexican prisoners cried out in recognition of their commander.[78] He was brought before Houston, who had been shot in the ankle and badly wounded.[80][Note 4] Texian soldiers gathered around, calling for the Mexican general's immediate execution. Bargaining for his life, Santa Anna suggested that he order the remaining Mexican troops to stay away.[84] In a letter to Filisola, who was now the senior Mexican official in Texas, Santa Anna wrote that "yesterday evening [we] had an unfortunate encounter" and ordered his troops to retreat to Béxar and await further instructions.[81]

Urrea urged Filisola to continue the campaign. He was confident that he could challenge the Texian troops. According to Hardin, "Santa Anna had presented Mexico with one military disaster; Filisola did not wish to risk another."[85] Spring rains had ruined the ammunition and rendered the roads nearly impassable, with troops sinking to their knees in mud. The Mexican troops were soon out of food and began to fall ill from dysentery and other diseases.[86] Their supply lines had broken down, leaving no hope of further reinforcements.[87] Filisola later wrote "Had the enemy met us under these cruel circumstances, on the only road that was left, no alternative remained but to die or surrender at discretion".[86]

For several weeks after San Jacinto, Santa Anna continued to negotiate with Houston, Rusk, and then Burnet.[88] Santa Anna suggested two treaties, a public version of promises made between the two countries, and a private version that included Santa Anna's agreements. The Treaties of Velasco required that all Mexican troops withdraw south of the Rio Grande and that all private property be respected and restored. Prisoners of war would be released unharmed, and Santa Anna would be given immediate passage to Veracruz. He secretly promised to persuade the Mexican Congress to acknowledge the Republic of Texas and to recognize the Rio Grande as the border between the two countries.[89]

When Urrea began marching south in mid-May, many families from San Patricio who had supported the Mexican army went with him. When Texian troops arrived in early June, they found only 20 families remaining. The area around San Patricio and Refugio suffered a "noticeable depopulation" in the Republic of Texas years.[90] Although the treaty had specified that Urrea and Filisola would return any slaves their armies had sheltered, Urrea refused to comply. Many former slaves followed the army to Mexico, where they could be free.[91] By late May, the Mexican troops had crossed the Nueces.[86] Filisola fully expected that the defeat was temporary and that a second campaign would be launched to retake Texas.[87]

Aftermath

Military

.jpg.webp)

When Mexican authorities received word of Santa Anna's defeat at San Jacinto, flags across the country were lowered to half staff and draped in mourning.[93] Denouncing any agreements signed by a prisoner, Mexican authorities refused to recognize the Republic of Texas.[94] Filisola was derided for leading the retreat and was replaced by Urrea. Within months, Urrea gathered 6,000 troops in Matamoros, poised to reconquer Texas. His army was redirected to address continued federalist rebellions in other regions.[95]

All the Mexican soldiers' bodies lay where they were killed for years or decades after the battle. Houston and Santa Anna both refused to order their soldiers to bury the dead so they lay on the property of Margaret "Peggy" McCormick who owned the land where the battle took place. Houston refused to bury the bodies because the Mexicans cremated all of the executed fallen Texan soldiers at Goliad and the Alamo and Santa Anna for some unknown reason refused to order his soldiers, now prisoners of war, to bury their fallen comrades. McCormick asked Houston in-person to bury the now rotting Mexican corpses, but Houston simply responded that she should be honored that her property is now the site of the battle that won Texan independence. Her family buried a few of the corpses but hundreds of them were never located by them. Many years later the corpses, now skulls and skeletons, were buried in a large trench on the battlefield site but nobody knows to the present day where the mass burial site is located.[96][97][98]

Most in Texas assumed the Mexican army would return quickly.[99] Such a large number of American volunteers flocked to the Texian army in the months after the victory at San Jacinto that the Texian government was unable to maintain an accurate list of enlistments.[100] Out of caution, Béxar remained under martial law throughout 1836. Rusk ordered that all Tejanos in the area between the Guadalupe and Nueces rivers migrate either to east Texas or to Mexico.[99] Some residents who refused to comply were forcibly removed. New American settlers moved in and used threats and legal maneuvering to take over the land once owned by Tejanos.[94][101] Over the next several years, hundreds of Tejano families resettled in Mexico.[94]

For years, Mexican authorities used the reconquering of Texas as an excuse for implementing new taxes and making the army the budgetary priority of the impoverished nation.[102] Only sporadic skirmishes resulted.[103] Larger expeditions were postponed as military funding was consistently diverted to other rebellions, out of fear that those regions would ally with Texas and further fragment the country.[102][Note 5] The northern Mexican states, the focus of the Matamoros Expedition, briefly launched an independent Republic of the Rio Grande in 1839.[104] The same year, the Mexican Congress considered a law to declare it treasonous to speak positively of Texas.[105] In June 1843, leaders of the two nations declared an armistice.[106]

Republic of Texas

On June 1, 1836, Santa Anna boarded a ship to travel back to Mexico. For the next two days, crowds of soldiers, many of whom had arrived that week from the United States, gathered to demand his execution. Lamar, recently promoted to secretary of war, gave a speech insisting that "Mobs must not intimidate the government. We want no French Revolution in Texas!", but on June 4 soldiers seized Santa Anna and put him under military arrest.[107] Burnet called for elections to ratify the constitution and elect a Congress,[108] the sixth set of leaders for Texas in a twelve-month period.[109] Voters overwhelmingly chose Houston the first president, ratified the constitution drawn up by the Convention of 1836, and approved a resolution to request annexation to the United States.[110] Houston issued an executive order sending Santa Anna to Washington, D.C., and from there he was soon sent home.[111]

During his absence, Santa Anna had been deposed. Upon his arrival, the Mexican press wasted no time in attacking him for his cruelty towards those executed at Goliad. In May 1837, Santa Anna requested an inquiry into the event.[112] The judge determined the inquiry was only for fact-finding and took no action; press attacks in both Mexico and the United States continued.[113] Santa Anna was disgraced until the following year when he became a hero of the Pastry War.[114]

Legacy

The San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960.[115] The site includes the 570 ft (170 m)[116] San Jacinto Monument, which was erected by the Public Works Administration. Authorized April 21, 1936, and dedicated April 21, 1939, the monument cost $1.5 million (equivalent to $32 million in 2022).[117][118] The site hosts a San Jacinto Day festival and battle re-enactment each year in April.[119]

Both the Texas Navy and the United States Navy have commissioned ships named after the Battle of San Jacinto: the Texan schooner San Jacinto and three ships named USS San Jacinto. There has been one civilian passenger ship named SS San Jacinto.

- Texas Navy schooner San Jacinto was commissioned in 1839 and decommissioned in 1840 after she was wrecked at Cayos Arcas.[120]

- The first USS San Jacinto was a screw frigate launched by the United States Navy in 1850. She was in service with the Africa Squadron in 1860 when she captured the slave ship Storm King. The frigate was in service for most of the American Civil War until she wrecked in the Bahamas in 1865.[121]

- SS San Jacinto was a United States civilian passenger ship built in 1903 by the Delaware River Iron Shipbuilding and Engine Works for the New York and Texas Steamship Company.[122] The U.S. Navy considered acquiring the civilian passenger-cargo ship for use during World War I as USS San Jacinto (ID-1531) but never acquired or commissioned her. On April 21, 1942, the ship was sunk by a German U-boat.[123]

- The second USS San Jacinto was a United States Navy Independence-class World War II light aircraft carrier commissioned in December 1943 and decommissioned in 1947.[124]

- The third USS San Jacinto is a decommissioned guided missile cruiser commissioned by the U.S. Navy in 1988 and decommissioned in 2023.[125]

When the veteran battleship USS Texas was decommissioned in 1948 and made into a museum ship, it was decided to give her a permanent anchorage near the San Jacinto Monument. Her arrival from Baltimore, where she was decommissioned, was timed for April 21, 1948 – the 112th anniversary of the Battle of San Jacinto.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Groce's Landing is located roughly 9 miles (14 km) northeast of modern-day Bellville. Moore (2004), p. 149.

- ↑ After getting inaccurate reports that several thousand Indians had joined the Mexican army to attack Nacogdoches, American General Edmund P. Gaines and 600 troops crossed into Texas. Reid (2007), pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Peggy Lake, also called Peggy's Lake, no longer exists. It was located southeast of the Mexican breastworks, which is now the site of the monument. Hardin (2004) pp. 71, 93

- ↑ Lamar thought Houston was deliberately shot by one of his men. Moore (2004), p. 339.

- ↑ New Mexico, Sonora, and California revolted unsuccessfully; their stated goals were a change in government, not independence. Henderson (2008), p. 100. Vazquez (1985), p. 318.

Citations

- ↑ "Picture and Key for "The Battle of San Jacinto" – Texas State Library and Archives Commission". Tsl.state.tx.us. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ The official report of the battle claims 783. The more detailed roster published after the battle lists 845 officers and men but failed to include Captain Wyly's Company, giving a total of around 910.

- ↑ General Samuel Houston, Texan Officials, HQ of the Army, April 25, 1836, reproduced in the Daily National Intelligencer, June 11, 1836, Vol. XXIV, Issue 7280, p. 2, Washington, DC

- ↑ Jackson, Wheat (2005), p. 28

- ↑ Poyo (1996), pp. 42–43, "Under the Mexican Flag" (Andrés Tijerina)

- ↑ Henderson (2008), pp. 86–87

- ↑ Jackson, Wheat (2005), pp. 30–31

- ↑ Jackson, Wheat (2005), pp. 49, 57

- ↑ Jackson, Wheat (2005), pp. 38–39

- ↑ Jackson, Wheat (2005), pp. 42–44, 208–283

- ↑ Davis (2004), p. 143.

- ↑ Todish et al. (1998), p. 121.

- ↑ Menchaca, Poche, Matovina, de la Teja (2013), p. 63

- ↑ "Surrender terms signed by General Cos and General Burleson at San Antonio, December 11, 1835". Texas State Library and Archives Commission. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ↑ Poyo (1996), p. 54, "Efficient in the Cause" (Stephen L. Harden)

- ↑ Calore (2014), p. 56

- ↑ Todish et al. (1998), pp. 137–138

- ↑ Hardin (2004), p. 15

- ↑ Todish et al. (1998), p. 34.

- ↑ Jackson, Wheat (2005), pp. 351–352

- ↑ Hardin (2004), p. 25

- ↑ Hardin (2004), p. 21

- ↑ Groneman, Gill. "Green B. Jameson". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 25, 2015.; Edmondson (2000), pp. 306–307; Jackson, Wheat (2005), pp. 367–368

- ↑ Poyo (1996), p. 53, 58 "Efficient in the Cause" (Stephen L. Harden); Lindley (2003), p. 94, 134

- ↑ Jackson, Wheat (2005), pp. 366–367, 208–283

- ↑ Hardin (2004), p. 53

- ↑ Jackson, Wheat (2005), p. 372

- ↑ Bishop, Curtis. "Battle of Agua Dulce Creek". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ↑ Hartmann, Clinton P. "James Walker Fannin Jr". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- 1 2 Hardin (1994), 161

- ↑ Lack (1992), p. 83

- ↑ Hardin-Teja (2010) pp. 64–66

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 14

- ↑ Jackson, Wheat (2005), pp. 373–374

- ↑ Moore (2004), pp. 37–38

- ↑ Moore (2004), pp. 43, 48, 52, 57.

- ↑ Moore (2004), pp. 55–59.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 71.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 60.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 243.

- 1 2 Hardin (1994), p. 182.

- 1 2 Hardin (1994), pp. 183–184.

- ↑ Moore (2004), pp. 71, 74, 87, 134.

- ↑ Moore (2004), pp. 134–137.

- 1 2 3 Hardin (1994), p. 189.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 263.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 185.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 254.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 154.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 176.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), p. 190.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 182.

- 1 2 3 Hardin (1994), p. 191.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), pp. 190–193.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), p. 209.

- 1 2 3 Hardin (1994), p. 202.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), pp. 200–201.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 258.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 283.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), p. 208.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 287.

- 1 2 Hardin (1994), p. 203.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), p. 204.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 267.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), p. 205.

- ↑ Houston, 1836, op cit

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 292.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 328.

- ↑ Houston, Texian Army HQ Report from San Jacinto, 1836 op cit

- 1 2 3 Houston, Texian Army HQ Report from San Jacinto, 1836, op cit

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 210.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 211.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 271.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), p. 213.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), pp. 211–215.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 274.

- 1 2 Hardin (1994), p. 215.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 364.

- 1 2 Davis (2006), p. 272.

- 1 2 Davis (2006), p. 273.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 276.

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 353.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), p. 216.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), p. 245.

- 1 2 3 Davis (2006), p. 277.

- 1 2 Hardin (1994), p. 246.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 279.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 282.

- ↑ Lack (1992), p. 180.

- ↑ Lack (1992), p. 245.

- ↑ Moore (2004) p. 242

- ↑ Henderson (2008), p. 103.

- 1 2 3 Davis (2006), p. 288.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 289.

- ↑ "Peggy McCormick". www.thealamo.org. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ↑ "TSHA | McCormick, Margaret". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ↑ "Dunn, Jeff. "The Mexican Soldier Skulls of San Jacinto Battleground". The Friends of the San Jacinto Battleground. April 1, 2010

- 1 2 Lack (1992), p. 201.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 291.

- ↑ Lack (1992), p. 206.

- 1 2 Vazquez (1985), p. 315.

- ↑ Henderson (2008), p. 125.

- ↑ Reid (2007), p. 169.

- ↑ Henderson (2008), p. 123.

- ↑ Henderson (2008), p. 127.

- ↑ Lack (1992), p. 104.

- ↑ Lack (1992), p. 107.

- ↑ Lack (1992), p. 256.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 295.

- ↑ Davis (2006), p. 301.

- ↑ Vazquez (1985), p. 316.

- ↑ Vazquez (1985), p. 317.

- ↑ Henderson (2008), p. 116.

- ↑ "San Jacinto Battlefield". National Historic Landmarks. National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ↑ "How Tall is it?". National Park Service. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ↑ Buisseret, Francaviglia, Graves, Saxon (2009), p. 75

- ↑ Moore (2004), p. 426.

- ↑ "San Jacinto Monument". Texas Parks & Wildlife Department. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ↑ "San Jacinto". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ↑ Silverstone (2006), p. 15

- ↑ "Mallory Line Twin-Screw Passenger and Freight Steamship San Jacinto". Marine Engineering. Marine Engineering Incorporated. VIII: 547–554. November 1903.

- ↑ Hampton Roads Naval Historical Foundation (2014), p. 71

- ↑ Green (2015), pp. 56, 107

- ↑ "USS San Jacinto". United States Navy. Archived from the original on August 19, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

References

- Buisseret, David; Francaviglia, Richard; Graves, Jack W. Jr.; Saxon, Gerald (2009). Historic Texas from the Air. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71927-9.

- Calore, Paul (2014). The Texas Revolution and the U.S.–Mexican War A Concise History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7940-5.

- Davis, William C (2004). Lone Star Rising: The Revolutionary Birth of the Texas Republic. New York, NY: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-68486-510-2.

- de la Teja, Jesus (1991). A Revolution Remembered: The Memoirs and Selected Correspondence of Juan N. Seguin. Austin, TX: State House Press. ISBN 0-938349-68-6.

- Edmondson, J.R. (2000). The Alamo Story-From History to Current Conflicts. Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press. ISBN 1-55622-678-0.

- Green, Michael (2015). Aircraft Carriers of the United States Navy: Rare Photographs from Wartime Archives. South Yorkshire, UK: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-47385-468-0.

- Hampton Roads Naval Historical Foundation (2014). Naval Station Norfolk. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-2027-2.

- Hardin, Stephen L; de la Teja, Jesús F. (2010). Tejano Leadership in Mexican and Revolutionary Texas. College Station, TX: Texas A & M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-166-7.

- Hardin, Stephen L. (1994). Texian Iliad – A Military History of the Texas Revolution. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-73086-1. OCLC 29704011.

- Hardin, Stephen (2004). The Alamo 1836 : Santa Anna's Texas campaign. Westport, CT: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-090-2.

- Hardin, Stephen; McBride, Angus (2001). The Alamo 1836: Santa Anna's Texas Campaign. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-090-2.

- Henderson, Timothy J. (2008). A Glorious Defeat: Mexico and Its War with the United States. New York, NY: Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-4967-7.

- Jackson, Jack; Wheat, John (2005). Almonte's Texas: Juan N. Almonte's 1834 Inspection, Secret Report & Role in the 1836 Campaign. Denton, TX: Texas State Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-87611-207-6.

- Lindley, Thomas Ricks (2003). Alamo Traces: New Evidence and New Conclusions. Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press. ISBN 1-55622-983-6.

- Menchaca, Antonio; Poche, Justin; Matovina, Timothy; de la Teja, Jesus (2013). Recollections of a Tejano Life: Antonio Menchaca in Texas History. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-29274-865-1.

- Moore, Stephen L. (2004). Eighteen Minutes: The Battle of San Jacinto and the Texas Independence Campaign. Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press. ISBN 1-58907-009-7.

- Poyo, Gerald Eugene (1996). Tejano Journey, 1770–1850. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-29276-570-2.

- Reid, Stuart (2007). The Secret War for Texas. Elma Dill Russell Spencer Series in the West and Southwest. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-565-3.

- Silverstone, Paul (2006). Civil War Navies, 1855–1883 (The U.S. Navy Warship Series). New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41597-870-5.

- Todish, Timothy J.; Todish, Terry; Spring, Ted (1998). Alamo Sourcebook, 1836: A Comprehensive Guide to the Battle of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution. Austin, TX: Eakin Press. ISBN 978-1-57168-152-2.

- Vazquez, Josefina Zoraida (July 1985). translated by Jésus F. de la Teja. "The Texas Question in Mexican Politics, 1836–1845". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 89. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- Zamora, Emilio; Orozco, Cynthia; Rocha, Rodolfo (2000). Mexican Americans in Texas History: Selected Essays. Denton, TX: Texas State Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-87611-174-1.

- https://www.tsl.texas.gov/treasures/giants/seguin/seguin-01.html#:~:text=In%20Gonzales%2C%20Segu%C3%ADn%20organized%20a,Sam%20Houston%20and%20Edward%20Burleson.

- https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/301368/harvest-of-empire-by-juan-gonzalez/

Further reading

External links

- Battle of San Jacinto – Handbook of Texas Online

- Flags of Guerrero and Matamoros Battalions – Texas State Library and Archives Commission

- San Jacinto Monument & Museum

- . . 1914.