| Battle of Le Transloy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Battle of the Somme of the First World War | |||||||

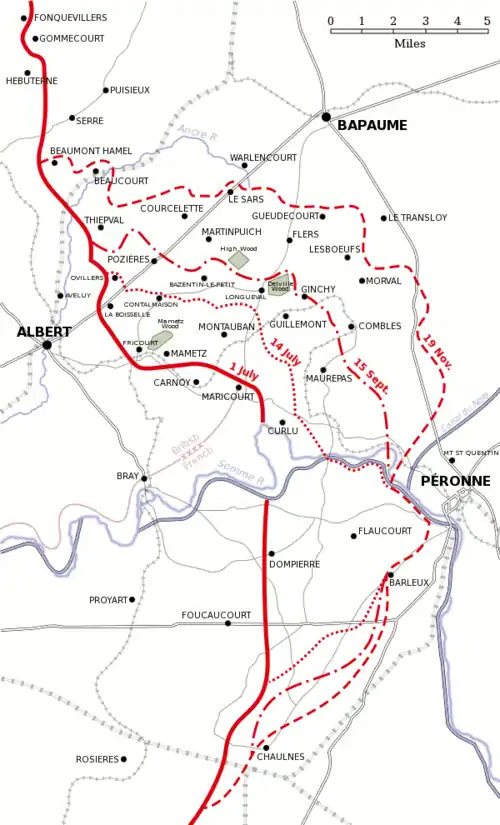

Battle of the Somme 1 July – 18 November 1916 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Douglas Haig Henry Rawlinson Ferdinand Foch Émile Fayolle Joseph Alfred Micheler |

Erich Ludendorff Kronprinz Rupprecht Fritz von Below Max von Gallwitz | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Fourth Army: 14 divisions Reserve Army: Canadian Corps | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

October: British: 57,722 (Fourth and Reserve Army total) French: 37,626 (Sixth Army and Tenth Army total) | October: 78,500 (1st Army and 2nd Army total) | ||||||

Le Transloy | |||||||

The Battle of Le Transloy was the last big attack by the Fourth Army of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in the 1916 Battle of the Somme in France, during the First World War. The battle was fought in conjunction with attacks by the French Tenth and Sixth armies on the southern flank and the Reserve/5th Army on the northern flank, against Army Group Rupprecht of Bavaria (Heeresgruppe Rupprecht) created on 28 August. General Ferdinand Foch, commander of groupe des armées du nord (GAN, Northern Army Group) and co-ordinator of the armies on the Somme, was unable to continue the sequential attacks of September because persistent rain, mist and fog grounded aircraft, turned the battlefield into a swamp and greatly increased the difficulty of transporting supplies to the front over the roads land devastated since 1 July.

The German armies on the Somme managed a recovery after the string of defeats in September, with fresh divisions to replace exhausted troops and more aircraft, artillery and ammunition diverted from Verdun or stripped from other parts of the Western Front. Command of the German Air Service (Die Fliegertruppen) was centralised and the new Luftstreitkräfte (German Air Force) was able to challenge Anglo-French air superiority with the reinforcements and new, superior, fighter aircraft. The German flyers further reduced the ability of the Anglo-French airmen to support the armies with artillery-observation and contact patrols in the rare periods of clear weather.

The German armies lost much less ground and had fewer casualties in October than in September but the proportion of casualties increased from 78.9 to 82.3 per cent of the Anglo-French total. Rain, fog and mud were lesser problems for the Germans, who had to carry supplies forward over a much narrower beaten zone and were being forced back onto undamaged ground. German bombardments on the few roads between the original front line and the line in October increased the difficulties of the British and French armies; the size and ambition of Anglo-French attacks was reduced progressively to local operations.[lower-alpha 1]

Every soldier endured miserable conditions but the Germans knew that the onset of winter would end the battle, despite the many extra casualties caused by illness. The British and French outnumbered the Germans and could relieve divisions after shorter periods in the line. Severe criticism of General Sir Douglas Haig and General Henry Rawlinson during and since the war for persisting with attacks on October, was challenged in 2009 by William Philpott, who put the British share of the battle into the context of strategic subordination to French wishes, the concept of a general Allied offensive established by Joffre and the continuation of French attacks south of Le Transloy which had to be supported by British operations. In a 2017 publication, Jack Sheldon translated overlooked German material on the ordeal endured by the German armies.

Background

Strategic developments

In September, Foch had managed to organise sequential attacks by the four Anglo-French armies on the Somme, which had captured more ground than any previous month and inflicted the worst monthly casualties on the Germans of the battle.[1][lower-alpha 2] During the Battle of Morval (25–28 September), the French Sixth Army (General Émile Fayolle) had crossed the Péronne–Bapaume road around Bouchavesnes, the Fourth Army (General Henry Rawlinson) had taken Morval, Lesbœufs and Gueudecourt in the centre and the Reserve Army (Lieutenant-General Hubert Gough), which became the Fifth Army on 30 October, had captured most of Thiepval Ridge on the left flank. On 29 September, General Sir Douglas Haig instructed the Fourth Army to plan operations to advance towards Bapaume, reaching Le Transloy on the right and Loupart Wood north of the Albert–Bapaume road on the left. The Reserve Army was to extend the attacks of the Fourth Army by making converging attacks on the Ancre valley after the Battle of Thiepval Ridge (26–28 September), by attacking northwards towards Loupart Wood, Irles and Miraumont on the south bank.[2]

On 28 August, the Chief of the General Staff General Erich von Falkenhayn simplified the German command structure on the Western Front by establishing two army groups. Armeegruppe Gallwitz–Somme was dissolved and General Max von Gallwitz reverted to the command of the 2nd Army.[3] Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht controlled the 6th, 1st and 2nd armies, from the Belgian coast to the boundary of Gruppe Deutscher Kronprinz, south of the Somme. The emergency in Russia caused by the Brusilov Offensive, the entry of Rumania into the war and French counter-attacks at Verdun put further strain on the German army. Falkenhayn had been sacked from Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL) on 29 August and replaced by ield Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff.[4] This Third OHL ordered an end to attacks at Verdun and the despatch of troops to Rumania and the Somme front.[5] Colonel Fritz von Loßberg, Chief of Staff of the 2nd Army, was also able to establish Ablösungsdivisionen (relief divisions) 6.2–9.3 mi (10–15 km) behind the battlefield, ready to replace tired divisions.[6]

German counter-attacks became bigger and more frequent, making the Anglo-French advance slower and more costly.[6] After the Anglo-French attacks in mid-September, a comprehensive relief of the front-line divisions had been possible.[7] On 5 September, proposals for a shorter line to be built in France were ordered from the commanders of the western armies, who met Hindenburg and Ludendorff at Cambrai on 8 September; the new leadership announced that no reserves were available for offensive operations, except those planned for Rumania. Ludendorff condemned the policy of holding ground regardless of its tactical value and advocated holding front-line positions with the minimum of troops and to recapture lost positions by counter-attacks.[5] On 21 September, after the battle of Flers–Courcelette (15–22 September), Hindenburg ordered that the Somme front was to have priority in the west for troops. During September, the Germans had sent another thirteen fresh divisions to the British sector and scraped up troops wherever they could be found. The German artillery had fired 213 train-loads of field artillery shells and 217 train-loads of heavy artillery ammunition, yet the début of the tank, the defeat at Thiepval (26–28 September) and the 130,000 casualties suffered by the armies on the Somme in September, had been severe blows to German morale.[8]

Tactical developments

German artillery on the Somme slowly improved in its effect, when Gallwitz centralised counter-battery fire and used aircraft reinforcements for artillery observation, which increased the accuracy and efficiency of bombardments.[9] The 2nd Army had been starved of reinforcements in mid-August, to replace exhausted divisions in the 1st Army and plans for a counter-stroke had been abandoned for lack of troops. Reinforcements for the Somme front in September began to reduce the German inferiority in guns and aircraft. Field artillery reduced its barrage frontage from 400–200 yd (370–180 m) per battery and increased its accuracy by using one air artillery flight (Artillerieflieger-Abteilung) per division.[5] As the Germans had been pushed out of their original defences, Loßberg established new positions based on principles of depth, dispersal and camouflage, rather than continuous lines of trenches. Rigid defence of the front-line continued but with as few soldiers as possible, relying on the firepower of machine-guns firing from behind the front-line and from the flanks. The area behind the front-line was defended by support and reserve units, dispersed on reverse slopes, undulations and in any other cover that could be found, so that they could open machine-gun fire by surprise, from unseen positions and then counter-attack swiftly, before French and British infantry could consolidate captured ground.[10]

The largest German counter-attacks of the Somme battle took place from 20 to 23 September, from the Somme north to St Pierre Vaast Wood and were destroyed by French artillery fire.[11] Rather than pack troops into the front-line, local, corps and army reserves were held back, in lines about 2,000 yd (1.1 mi; 1.8 km) apart, able to make progressively stronger counter-attacks.[10] Trenches were still dug but were no longer intended to be fought from, being used for shelter during quiet periods, for the movement of reinforcements and supplies and as rallying points and decoys. Before an attack, the garrison tried to move forwards into shell-holes, to avoid Allied artillery-fire and to surprise attacking infantry with machine-gun fire.[10] Opposite the French, the Germans dug new defences on a reverse slope from the Tortille stream at Allaines to the west end of St Pierre Vaast Wood and from there to Morval. Riegel I Stellung, the fourth German position, was dug from Sailly Saillissel to Morval and Bapaume, along the Péronne–Bapaume road. French agents also reported new construction 22 mi (35 km) to the east. Ludendorff created fifteen "new" divisions by combing-out troops at depots and by removing regiments from existing divisions; the new 212th, 213th and 214th divisions replaced worn out divisions opposite the French Tenth and Sixth armies.[12]

Prelude

Anglo-French plan

Fayolle planned attacks to capture Sailly-Saillisel, a twin village to the north-west of St Pierre Vaast wood, followed by outflanking attacks to the north and south, avoiding a frontal attack. Fayolle expected to be ready to attack Sailly-Saillisel by 7–8 October but if an attack towards Rocquigny could begin earlier, the Fourth Army was to attack to cover the French left flank. Sailly-Saillisel was along the Péronne–Bapaume road and Saillisel lay at right angles on the east side, along the Moislains–St Pierre Vaast road and overlooked a shallow valley to the north towards Le Transloy. The difficulties of movement in the rear, wet weather in October and the terrain channelled the attacks of the Sixth Army into a gap between St Pierre Vaast Wood and the Fourth Army boundary. At the end of September, the Sixth Army took over the Fourth Army front at Morval, which widened the attack front to about 2.5 mi (4 km). The French XXXII Corps, which held the front from Rancourt to Frégicourt, was to attack the Saillisels and I Corps to the left would attack eastwards from Morval, to capture Bukovina and Jata-Jezov trenches in the German fourth position in front of the Péronne–Bapaume road, then capture the north end of the Saillisels and reach Rocquigny.[13]

The British Fourth, Reserve and Third armies were to be ready by 12 October, the Fourth Army to attack towards Le Transloy, Beaulencourt, the ridge beyond the Thilloy–Warlencourt valley to Loupart Wood (about a mile east of Irles). Before the main attack, the Fourth Army was to advance north-eastwards, to capture a spur west of Le Transloy and Beaulencourt and north to the edge of the Thilloy–Warlencourt valley. Haig thought that if there was normal autumn weather, the objectives could be achieved but some restrictions on artillery ammunition consumption were imposed and more aircraft were requested from England. An attack on 1 October was to advance the left flank, capture Eaucourt and part of the Flers line (also known as the Le Sars line) up to Le Sars.[14] The Reserve Army was to advance towards Puisieux, as the right flank met the attacks from the south bank at Miraumont, enveloping German troops in the upper Ancre valley. The Third Army was to provide a flank guard north of the Reserve Army, by occupying a spur south of Gommecourt. Operations were to begin by 12 October, after the Fourth Army had attacked towards Le Transloy and Beaulencourt and the French Sixth Army had attacked Sailly-Saillisel. The French Tenth Army south of the Somme was to attack on 10 October, north of Chaulnes.[2]

Fourth Army

The attack was to be conducted by III Corps and the New Zealand Division of XV Corps on the right flank, which was to advance its left, pivoting from a point in the Gird trenches, 1,500 yd (1,400 m) east of Eaucourt. On 29 September, a day of rain and bright spells, the 6th Division and the Guards Division in XIV Corps on the right flank, took unopposed, some trenches east of Lesbœufs at 5:30 a.m. A company of the 8th Battalion York and Lancaster Regiment of the 23rd Division captured Destrémont Farm and gained contact with the 2nd Canadian Division (II Corps) on the right flank of the Reserve Army later on; a battalion of the 47th (1/2nd London) Division began to bomb its way up Flers Trench during the evening. On 30 September, the day was dull but dry; the battalion pushed the Germans back beyond Flers Switch Trench and a New Zealand battalion kept pace along Flers Support Trench.[15]

German preparations

The Germans had built new defensive lines during the battle and the first two were called the Riegel I Stellung/Allainesstellung (Switch Trench I Position/Allaines Line), a double line of trenches and barbed-wire several miles further back, as a new second line of defence along the ridge north of the Ancre valley, from Essarts to Bucquoy, west of Achiet le Petit, Loupart Wood, south of Grévillers, west of Bapaume to Le Transloy and Sailly-Saillisel. On the reverse slope of that ridge, the Riegel II Stellung/Arminstellung (Switch Trench II Position/Armin Line) ran from Ablainzevelle to west of Logeast Wood, west of Achiet le Grand, the western outskirts of Bapaume, to Rocquigny, Le Mesnil en Arrousaise to Vaux Wood. Riegel III Stellung branched from Riegel II Stellung at Achiet le Grand and ran clockwise around Bapaume, then south to Beugny, Ytres, Nurlu and Templeux la Fosse.[16] The first two German reserve lines had various British titles (Loupart/Bapaume/le Transloy/Bihucourt lines) and the third line was known as the Beugny–Ytres Switch.[17]

From 25 September to the beginning of October, Rupprecht relieved the 6th Bavarian Division, 50th Reserve Division and the 52nd Reserve Division with the 7th Reserve Division, 6th Bavarian Reserve Division and 18th Reserve Division opposite the Fourth Army, part of thirteen fresh divisions installed opposite the British.[18] From 30 September – 13 October, the six divisions from Le Transloy to the Ancre river were relieved by seven fresh divisions, two of which were then relieved by the 6th Division, 2nd Bavarian Division, 19th Reserve Division, 28th Reserve Division, 24th Division, 40th Division, 4th Ersatz Division, 5th Ersatz Division and Marinekorps-Flandern from the Belgian coast.[8] From 24 October – 10 November, the seven divisions from Le Transloy to the Ancre were relieved, as was one of the fresh divisions, by the 38th Division, 222nd Division, Bavarian Ersatz Division, 4th Guard Division, 58th Division, 1st Guards Reserve Division, 23rd Reserve Division and the 24th Reserve Division; in mid-November, the Marine Brigade reinforced the Guard Reserve Corps near Warlencourt.[19]

Battle

Fourth Army

1 October

At 7:00 a.m. on a fine day, a deliberate bombardment began along the Fourth Army front and continued steadily until zero hour at 3:15 p.m. In the Gird trenches on the right flank, captured during the preliminary operations, the Special Brigade RE fired oil cylinders from 36 Livens Projectors, a minute before the attack by the New Zealand Division on the left of XV Corps (Lieutenant-General John Du Cane). Thirty of the cylinders burst on target, enveloping the objective in flame and smoke. Despite the bombs, German machine-gunners inflicted many casualties on the depleted 2nd Canterbury and 2nd Otago battalions of the 2nd New Zealand Brigade. The 2nd Canterbury captured quickly the Gird trenches up to Goose Alley and the east end of Circus Trench, which was on a south-west line down to the Flers trenches. The 2nd Otago attacked from Goose Alley and passed beyond the objective and The Circus, an empty German strong point. The New Zealanders reorganised on the Le Barque road and with reinforcements consolidated a new line, in contact with the 47th Division (Brigadier-General W. H. Greenly then Major-General George Gorringe) near Abbey Road. The New Zealanders lost many of the 850 men still left during the attack and took 250 prisoners.[20]

On the right flank of the III Corps (Lieutenant-General William Pulteney) area on the left flank of the Fourth Army, the 47th (1/2nd London) Division attacked with three battalions of the 141st Brigade and two tanks. The 1/19th London Regiment (1/19th London) got to within 50 yd (46 m) of the German line, was forced under cover by machine-gun fire and waited for the tanks. The tanks drove left along the Flers trenches firing into them and the infantry captured the trenches easily, despite the many earlier casualties. As the support waves consolidated Flers Support Trench, the leading infantry pressed on past Eaucourt L'Abbaye (Eaucourt) and met the New Zealanders at the Le Barque road. The 1/20th London attacked Eaucourt and crossed the Flers trenches after the two tanks has passed by, swept through Eaucourt and gained touch with the 1/19th London. The tanks pressed on but bogged west of Eaucourt; the 1/17th London on the left flank had already been stopped by uncut wire and German machine-gun fire. During a counter-attack by part of II Battalion, Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 17, the tanks were set on fire and abandoned.[21]

| Date | Rain (mm) |

°F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 63–41 | fine dull |

| 2 | 3 | 57–45 | wet mist |

| 3 | 0.1 | 70–50 | rain mist |

| 4 | 4 | 66–52 | dull wet |

| 5 | 6 | 66–54 | dull rain |

| 6 | 2 | 70–57 | sun rain |

| 7 | 0.1 | 66–52 | wind rain |

| 8 | 0.1 | 64–54 | rain |

| 9 | 0 | 64–50 | fine |

| 10 | 0 | 68–46 | fine sun |

| 11 | 0.1 | 66–50 | dull |

| 12 | 0 | 61–55 | dull |

| 13 | 0 | 61–50 | dull |

| 14 | 0 | 61–50 | dull |

| 15 | 3 | 57–41 | rain fine |

| 16 | 0.1 | 54–36 | sun cold |

| 17 | 3 | 55–43 | fine |

| 18 | 4 | 57–48 | rain fine |

| 19 | 4 | 57–37 | rain |

| 20 | 0 | 48–28 | fine cold |

| 21 | 0 | 45–28 | fine cold |

| 22 | 0 | – – | fine cold |

| 23 | 3 | 55–43 | dull |

| 24 | 3 | 54–45 | dull rain |

| 25 | 2 | 52–45 | rain |

| 26 | 1 | 55–39 | rain |

| 27 | 1 | 55–43 | rain cold |

| 28 | 8 | 55–41 | wet cold |

| 29 | 7 | 53–45 | wet |

| 30 | 7 | 61–48 | wet cold |

| 31 | 0 | 63–46 | — |

| 1 | 3 | 59–46 | — |

| 2 | 3 | 59–48 | — |

| 3 | 1 | 59–48 | — |

| 4 | 2 | 64–52 | wet cloud |

| 5 | 0 | 59–48 | clear |

| 6 | 0 | 57–45 | cloud |

| 7 | 12 | 55–45 | — |

| 8 | 2 | 57–43 | — |

| 9 | 0 | 54–30 | bright clear |

| 10 | 0 | 50–30 | — |

| 11 | 0.1 | 55–32 | mist frost |

The 50th (Northumbrian) Division (Major-General Percival Wilkinson) attacked with the 151st Brigade. On the right the 1/6th Durham Light Infantry (1/6th DLI) was exposed by the repulse of the 1/17th London, had many casualties from German machine-gun fire and was only able to capture a short length of Flers Trench. The 1/9th DLI (Lieutenant-Colonel R. B. Bradford) came up from reserve and Bradford managed to organise another attack, capturing the rest of Flers Trench by 9:30 p.m. In the centre, a composite battalion of the 1/5th Border, 1/8th DLI and the 1/5th Northumberland Fusiliers attached from the 149th Brigade on the left, benefited from an excellent barrage to advance and capture the Flers trenches before the defenders could react.[23]

On the left flank of III Corps, the 23rd Division (Major-General James Babington) attacked with the 70th Brigade. The 11th Sherwood Foresters (11th Foresters) and the 8th King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (8th KOYLI) assembled forward of their trenches, which were on a south-east line from Destrémont Farm. On the right, the 11th Foresters captured Flers Trench and most of Flers Support then linked with the 151st Brigade. On the left, the 8th KOYLI faced determined resistance and only later was able to bomb the Germans back up Flers Trench and link with the 2nd Canadian Division on the Reserve Army boundary. The 9th York and Lancs went forward to reinforce and tried to probe Le Sars but was repulsed by small-arms fire from the houses. Communication with the rear broke down and the divisional and corps headquarters were not reliably informed of events until early on 2 October. The 47th (1/2nd London) Division headquarters realised that the 1/17th London had been repulsed and sent forward the tired and understrength 1/23rd London (142nd Brigade), which repeated the attack at 6:54 a.m. and was repulsed with 170 casualties.[24]

2–6 October

During the night of 1/2 October, the Germans were forced out of Flers Support on the 50th Division front, where the 1/6th and 1/9th DLI formed a flank guard on the right next to the 47th Division and defeated several German counter-attacks, with hand grenades and Stokes mortar fire. It began to rain at 11:00 a.m. and continued for the next two days. The 1/18th London relieved the 1/17th London and at midday on 3 October, patrols reported that there were few Germans in the trenches opposite Eaucourt. The battalion advanced nearly unopposed north-west of the farm and gained touch with the 1/20th London on the right and the 68th Brigade of the 23rd Division, which had relieved the 50th Division brigade. Opposite Le Sars on the left, the 69th Brigade took over from the 70th Brigade and on 4 October, was repulsed in a pre-dawn attack up Flers Support to cross the Albert–Bapaume road. The next Fourth Army attack had been set for 5 October but the rains forced Rawlinson to postpone the attack until 7 October. The Sixth Army agreed to the postponement so that the attacks of both armies would simultaneous.[25]

The 47th (1/2nd London) Division occupied the rest of Flers Support on 4 October and during the night of 5 October occupied the site of a mill to the north-west of Eaucourt; the 23rd Division attacked to capture Flers Support north of the Albert–Bapaume road at 6:00 p.m. on 4 October. A small party of the 10th Battalion Duke of Wellington's Regiment cut through the barbed wire by hand and got a footing in the trench but retired after running out of grenades and ammunition. Two days later, the 11th Northumberland Fusiliers captured the Tangle east of Le Sars but found the area untenable and retired. The weather improved on 4 October, with high winds and little rain but low cloud made air observation difficult. On the XIV Corps front, it as was difficult to identify German outposts in trenches and derelict gun pits in front of the fortifications of Le Transloy, as it was for the British positions opposite. A high volume of German artillery retaliation when the preliminary bombardment began on 6 October, was maintained but caused few casualties to British troops waiting for zero hour at 1:45 p.m.[26]

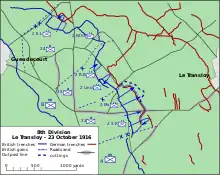

7 October

The XIV Corps objective was a trench line from 100–500 yd (91–457 m) away and on the right flank the 56th (1/1st London) Division (Major-General Charles Hull) attacked with two brigades. On the right, in the 168th Brigade area, the 1/14th Battalion London Scottish found it difficult to maintain contact with the French on the right, who advanced eastwards rather than north-east. The Scottish captured a southern group of gun pits and pushed on to the south end of Hazy Trench 200 yd (180 m) beyond. The 1/4th London was stopped by machine-gun fire from the northern gun pits and tried to outflank them on the right. On the left, the 1/12th London advance was stopped short of Dewdrop Trench to the north-east of Lesbœufs, which had only been bombarded by Stokes mortars as it was too close to the British front line. In the 167th Brigade area, the 1/1st London was repulsed in front of Spectrum Trench except on the left flank where bombers joined with the 1/7th Middlesex, after it captured Rainbow Trench, the south end of Spectrum Trench against determined resistance. The 1/14th London Scottish and the 1/4th London defeated a counter-attack but after dark the battalions were forced back, as were the French on the right.[27]

In the 20th (Light) Division (Major-General William Smith) area two battalions of the 60th Brigade captured Rainbow Trench, shot at German troops who ran away and pressed on 150 yd (140 m) to Misty Trench to gain touch with the 1/7th Middlesex on the right and the 61st Brigade on the left, which had reached its objective east of Gueudecourt, after the 7th KOYLI and the 12th King's Liverpool encountered a line of Germans advancing from Rainbow Trench to surrender. The battalions occupied Rainbow Trench and kept going to 300 yd (270 m) to the south-east corner of Cloudy Trench. The 12th (Eastern) Division (Major-General Arthur Scott) on the right of XV Corps had not moved forward, so a defensive flank was formed on the left and a new trench (Shine Trench) dug from Cloudy Trench to the Beaulencourt road. About 350 yd (320 m) of Rainbow Trench south-east of the road was still held by the Germans, who counter-attacked from Beaulencourt at about 5:00 p.m. and were repulsed by small-arms fire.[28]

In the XV Corps area, the objective was set 300 yd (270 m) forward along the north-west end of Rainbow Trench and Bayonet Trench (the west end of which, beyond the Flers–Thilloy road, had just been discovered), up to the Gird trenches. Just before zero hour a German machine-gun barrage began on the front trenches of the 12th (Eastern) Division and began an artillery bombardment, particularly on Gueudecourt, which held back the 37th Brigade on the right flank. The 6th Buffs next to the 20th Division got into Rainbow Trench with too few survivors to consolidate and retired. The 6th Royal West Kent on the left was stopped by the machine-gun barrage as were the 9th and 8th Royal Fusiliers of the 36th Brigade on the left, the parties of the 8th Royal Fusiliers which got into Bayonet Trench being overwhelmed.[29] In the 41st Division (Major-General Sydney Lawford) area on the left of XV Corps, the German machine-gun barrage stopped the 32nd and 26th Royal Fusiliers of the 124th Brigade half-way to Bayonet Trench. Parties reached the trench, where they were reinforced by the 21st KRRC and 10th Queen's but by nightfall, the brigade had been reduced to a battalion of survivors. On the left flank, the 122nd Brigade used all four battalions who were also shot down. A Livens Projector bombardment of burning oil on the Gird lines failed but bombers from the 11th West Kent advanced a short way up both trenches. On the left flank, the divisional and corps boundary, the brigade got forward and linked with the 47th Division on the right of III Corps.[30]

In the III Corps area, the 47th (1/2nd London) Division and 23rd Division objective required an advance of 500 yd (460 m), half-way into Le Sars and then capture the rest of the village when the offensive began on the Butte de Warlencourt and the Gird trenches up to the Flers trenches. The 47th (1/2nd London) Division attacked with the 140th Brigade to capture Snag Trench along the east slope of a dip towards Warlencourt, about 500 yd (460 m) forward and half way to the butte. The 1/8th London on the right was stopped by a huge volume of machine-gun fire, as were the 1/15th and 1/7th London who were to pass through the 1/8th London and could only establish outposts near the Le Barque road, in touch with the 41st Division. The 23rd Division attacked on the right with the 12th DLI of the 68th Brigade, supported by a tank which attacked the German garrison in the Tangle and then turned left up the sunken road from Eaucourt to Le Sars, until hit by a shell. The 12th DLI was checked by machine-gun fire down the road from the village but the 9th Green Howards of the 69th Brigade got into the south-west end. In the centre, the 13th DLI was to capture the rest of the village and attacked at 2:30 p.m.[31]

The battalion met the Green Howards at the village crossroads and after a determined resistance, the German defence collapsed. The 12th DLI had dug in along the sunken road beyond the Tangle and pushed posts forward on the right flank. The 13th DLI and Green Howards dug posts around the village and prepared to advance on the Butte de Warlencourt but no reinforcements were available.[31] Twenty minutes after zero hour, the 11th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment made a frontal attack on Flers Support Trench north of Le Sars but was stopped by artillery-fire and small-arms fire from the left flank. A second attempt succeeded, with bombers attacking along the trench from Le Sars, retreating Germans being shot down by the British infantry and the divisional artillery. The 10th Duke of Wellington's arrived later and by dark, the 69th Brigade had occupied the Flers trenches to a point 300 yd (270 m) inside the Fourth Army boundary.[32]

8 October

The rain came back during the night and on 8 October the Fourth Army divisions removed casualties and consolidated positions. On the left flank the 23rd Division attacked again at 4:50 a.m. with the Reserve Army. Two companies of the 8th York and Lancs from the 70th Brigade, captured the Flers trenches up to the army boundary and occupied an abandoned post 750 yd (690 m) north-west of Le Sars. The 47th (1/2nd London) Division made a night attack on Snag Trench with the 1/21st and 1/22nd London, by crawling forward to rush the trench as the barrage lifted. The trench was entered on the left but the parties were forced out by fire from the right. The 1/22nd London set up posts on the Eaucourt–Warlencourt road and gained touch with the 23rd Division to the west. On the army boundary with the Sixth Army, the 56th Division moved back from Rainy Trench north-east of Lesbœufs and most of Spectrum Trench to the north, for a British preparatory bombardment and then attacked at 3:30 p.m., with the 169th Brigade on the right. The 1/5th London (London Rifle Brigade) captured Hazy Trench, despite losing contact with the French 18th Division on the right and machine-guns concealed in shell-holes stopped the 1/9th London and the 1/3rd London (167th Brigade) advance on Dewdrop and Spectrum trenches. After dark the battalions were withdrawn to the start line and German troops occupied Rainy trench unopposed.[33]

Late on 8 October, Rawlinson ordered another attack, once XV Corps had reached its objectives, anticipated to be by 12 October, when the Sixth Army expected to have captured Sailly-Saillisel to the south-east. The rain stopped early on 9 October and from 10 to 11 October, the weather was fine but the state of the ground made divisional reliefs slow and laborious. From 8–11 October, the XIV Corps replaced the 56th and 20th divisions with the 4th Division (Major-General William Lambton) and the 6th Division (Major-General Charles Ross). In XV Corps the 41st Division was replaced by the 30th Division (Major-General John Shea) and the 9th Division (Major-General William Furse) and 15th Division (Major-General Frederick McCracken) took over from the 47th (1/2nd London) and 23rd divisions in III Corps. The new division had little time to study the ground or dig assembly trenches and Furse was refused a 48-hour postponement. The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) attempted to get new photographs of the German defences but the light was too poor for much to be achieved.[34]

12 October

Zero hour was 2:05 p.m. and the 4th Division on the right of XIV Corps attacked with the 10th Brigade next to the French 18th Division (IX Corps). The 1st Battalion, Royal Warwick advanced 500 yd (460 m) and dug Antelope Trench south of Hazy Trench, gained touch with the French and repulsed a counter-attack in the evening. The battalion advance was repulsed at Rainy and Dewdrop trenches north-east of Lesbœufs, along with the 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers further to the left. On the left of the division the 12th Brigade attacked Spectrum Trench after a Stokes mortar bombardment; parties of the 2nd Duke of Wellington got into the trench and linked with the 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers in the north end of the trench. An attempt by groups from both battalions to attack over the spur to Zenith Trench was repulsed. In the 6th Division area north of the Le Transloy road, the 2nd York and Lancaster, on the right of the 16th Brigade was also repulsed in front of Zenith Trench.[35]

In the 71st Brigade area to the left, the 9th Suffolk in a salient formed by Misty and the east end of Cloudy Trench were not to advance and in the 18th Brigade on the left of the division, the 1st West Yorks attacked Mild Trench and the rest of Cloudy Trench by a frontal attack and a flank attack by bombers, which was repulsed. The 14th DLI on the left flank got into Rainbow Trench and bombed dugouts along the sunken Beaulencourt road, to link with the 1st West Yorks. On the left of the road the 14th DLI gained touch with the 88th Brigade detached from the 29th Division to the 12th (Eastern) Division on the right of XV Corps. The Royal Newfoundland Regiment on the right and the 1st Essex on the left, captured part of Hilt Trench and the extension of Rainbow Trench and then part of the 1st Essex pressed on to Grease Trench but were ordered back to the start line at 5:30 p.m. because the 35th Brigade on the left had not managed to get forward. The Newfoundlanders held on at Hilt Trench, bombed further up and took part of the 1st Essex objective. In the 35th Brigade attack, the 7th Suffolk and the 7th Norfolk tried to cut through barbed wire by hand opposite Bayonet Trench against massed small-arms fire, after which the survivors were pinned down until dark and then retreated.[36]

The 30th Division attacked on the left of XV Corps with the 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers and the 17th Manchester of the 90th Brigade. The Royal Scots managed only to advance 150 yd (140 m) into machine-gun fire and then withdrew as some parties of the 17th Manchester got into Bayonet Trench before retiring. On the left of the division, the 89th Brigade attacked on the right with the 2nd Bedfordshire, which tried to bomb up the Gird trenches but were only able to take a small length of Bite Trench. On the left, the 7th King's Liverpool was stopped by enfilade fire from the north-west, the preliminary bombardment having failed to suppress the German machine-guns, which were dispersed over a wide area.[37]

In the III Corps area the 9th (Scottish) Division on the right had to capture Snag Trench, then the Butte de Warlencourt and the Warlencourt line. The Tail ran back from Snag Trench to the butte and the Pimple at the west end of Snag Trench, with the help of enfilade fire from the 15th (Scottish) Division to the left. Little Wood and the butte were bombarded with smoke by 4 Special Company RE. In the 26th Brigade on the right, the 7th Seaforth Highlanders was caught by machine-gun fire as soon as it attacked and with the reinforcement of the 10th Argylls managed only to push on for 200 yd (180 m) and dig in during the night. On the left flank the 1st South African Brigade attacked with the 2nd Regiment followed by the 4th Regiment, which were held up by long-range machine-gun fire and lost direction in the smoke drifting from the butte. Parties dug in half-way to Snag Trench and some stayed in no man's land until the following morning.[38]

14–17 October

After the poor results of the attack on 12 October, Rawlinson concluded that the weather delays had enabled the defenders to recover and that a deliberate attack after methodical bombardment was necessary, before another attack on 18 October. On 13 October, he issued an operation order in which he stressed the necessity of improving routes to the front line and the preparation of good assembly trenches parallel to the German defences. A steady bombardment was to begin immediately and XIV Corps was warned to capture Zenith, Mild and the rest of Cloudy trenches, before the general attack. XV Corps was to capture the Gird lines south-east of the Eaucourt–Le Barque road and Snag Trench was to be captured by III Corps, all by night attacks supported by tanks, where practical. On 14 October, the XIV Corps attempted a surprise attack at 6:30 p.m. with the 2nd Seaforth of the 4th Division, which got into Rainy Trench and gun-pits south of Dewdrop Trench and were then forced out by a counter-attack. The 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers tried to capture gun-pits in front of Hazy Trench at the same time and were also repulsed.[39]

In the 12th Brigade, the 1st King's Own tried to bomb down Spectrum Trench to Dewdrop Trench in the evenings of 14 and 15 October and in a pre-dawn attack on 15 October, the 2nd Sherwood Foresters in the 6th Division took the gun-pits in front of the British-held section of Cloudy Trench and took several prisoners. On the left of the division the 11th Essex overran Mild Trench and bombed up the Beaulencourt road before being forced back by a counter-attack. In the III Corps area, the 3rd South African Regiment attacked after dark on 14 October, captured the Pimple and 80 yd (73 m) of Snag Trench. The rain gradually abated and 17 October began fair but clouded over and rain fell again during the night. The British bombardment had continued as planned but the German artillery reply was vigorous leading up to zero hour at 3:40 a.m. on 18 October.[40]

18–20 October

On most of the brigade fronts, assembly positions had been marked with white tape and compass bearings taken of the direction to the objectives but at zero hour, the British positions were flooded. The moon was obscured by low clouds, troops slipped and fell in the mud and weapons were clogged, leaving only hand grenades and bayonets with which to fight. On the right the 4th Division attacked with the 11th Brigade to take Frosty, Hazy, Rainy and Dewdrop trenches, while in the French sector the attack began at 11:45 a.m. Groups of the 1st Rifle Brigade reached the gun-pits before Hazy Trench and were forced back, the 1st East Lancs were forced under cover in front of Dewdrop Trench, by the fire of hidden machine-guns. The 1st King's Own of the 12th Brigade and the German defenders mutually attacked and counter-attacked around Spectrum Trench and then the King's Own bombed along Spectrum for 70 yd (64 m) towards Dewdrop Trench. In the 6th Division, the 9th Norfolk attacked Mild and Cloudy trenches but was bombarded before zero hour and moved so slowly through mud that it lost the barrage. The battalion captured the north-west end of Mild Trench and then repulsed a counter-attack as dark fell. (After dark on 19 October, a platoon of the 1st Somerset Light Infantry found Frosty Trench unoccupied and defeated a counter-attack.)[41]

The XV Corps made flank attacks because the centre faced a dip either side of the Flers–Thilloy road. The 12th (Eastern) Division on the right attacked Grease Trench with the 2nd Hampshire and 4th Worcester battalions and the south-east end of Bayonet Trench with the 9th Essex battalion from the 35th Brigade. The 2nd Hampshire and the 4th Worcester took Grease Trench with few losses but then had many casualties trying to press on. The Worcester blocked Hilt Trench on the left after the 9th Essex were not able to advance, except for one company which got into Bayonet Trench and was then bombed out by counter-attacks from the flanks. On the left of the 30th Division the 2nd Green Howards almost reached the west end of Bayonet Trench before being stopped by showers of hand-grenades. Parties bombed up part of Bite Trench but reinforcements were stopped from moving up by the mud. On the left the 18th King's and 2nd Wiltshire attacked the Gird lines and found uncut wire on the right and enfiladed from the left, most of the 2nd Wiltshire being killed.[42]

Two tanks had been brought up to Flers in case the night attacks failed and during a lull at 8:00 a.m. one bogged in mud and the other drove to the end of Gird Trench and machine-gunned it for twenty minutes, killing many Germans who ran back to the north-east. The commander signalled the infantry to move up but the infantry were so disorganised and exhausted that none moved. The tank drove along Gird Trench to the Le Barque road and then returned. III Corps attacked Snag Trench again as smoke and lachrymatory bombs were fired from the 15th (Scottish) Division front to try to suppress German fire from the butte and from Warlencourt village. The 5th Cameron Highlanders, on the right of the 9th (Scottish) Division, took a trench from the Le Barque road to 200 yd (180 m) from the Nose (the junction of Snag Trench and the Tail) and met some of the 2nd Wiltshire.[43]

A German counter-attack on the right got a footing in the trench, until another attack after dark drove them back and on the left two companies of the 1st South African Regiment overran Snag Trench, pressed on and were shot down by machine-gun fire from the butte, apart from a small group who got into Snag Trench next to the Cameron. At dawn the South Africans tried to bomb along Snag from the Pimple and at 5:45 p.m. attacked from both flanks. The South Africans managed to advance, leaving the Germans occupying only 100 yd (91 m) of the trench around the Nose as night fell.[43] The rain continued during 19 October; at dawn, German parties accompanied by a Flammenwerfer detachment advanced along the Tail to attack eastwards along Snag Trench. The South Africans retreated towards the 8th Black Watch which had relieved the Cameron as a counter-attack on the right flank was repulsed. British artillery maintained the bombardment on the Nose and Tail areas but the South African Brigade was too exhausted to attack again and after dark the 27th Brigade took over all the 9th (Scottish) Division front, struggling through mud and water. The 6th King's Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB) was considered fit to attack at 4:00 p.m. on 20 October and in confused fighting, captured, lost and retook the Nose. By dark the 6th KOSB had control of Snag Trench and some Royal Scots had advanced along 250 yd (230 m) of the Tail.[44]

German 1st and 2nd armies

1–3 October

In the early autumn, many German divisions which had fought earlier on the Somme were brought back for a second period, in which their performance was considered inferior, despite replacements being of good quality, because of their lack of experienced NCOs and junior officers. The 6th Bavarian Reserve Division took over the defences of Eaucourt l'Abbaye (Eaucourt) on 26 September and suffered many casualties to artillery-fire. On 1 October, prisoners taken from Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 21 (BRIR 21) of the division said that Brandbomben (Livens Projectors) had caused much damage. BRIR 21 recorded the capture of the II and III battalion headquarters and that attempts to counter-attack failed. The II Battalion, BRIR 17 counter-attacked south-east down the Flers trenches past two bogged-down tanks but hope to recover Eaucourt were abandoned during the afternoon.[45] The III Battalion, BRIR 17 re-assembled on the Eaucourt–Le Sars road on 2 October and was joined by III Battalion, BRIR 16 and parties of Infantry Regiment 362 of the 4th Ersatz Division garrisoned the village.[46][lower-alpha 3]

On the night of 2/3 October, BRIR 21 was relieved near Eaucourt by BRIR 16 but the fresh troops were unable to prevent the loss of Eaucourt. The infantry were ground down by the weather conditions and British attacks. The commander of I Battalion, BRIR 16 reported that battlefield conditions were extraordinary, with cold food and artillery-fire causing severe problems, particularly short shooting by German guns, the high number of casualties having depressed morale, made worse by the lack of opportunity to remove the bodies strewn around trenches and tracks. Poor hygiene caused many non-battle casualties, with 25 to 33 per cent of the men having severe diarrhoea. The report was sent to the regiment commander who could only pass it on.[46] By 3 October, the 4th Ersatz Division had relieved the 7th Division west of the Bapaume road and took over the Bavarian right up to Le Sars, by when BRIR 17 casualties had risen to 1,646 men.[48]

7–8 October

On the night of 6/7 October, Infantry Regiment 68 (IR68) of the 16th Division and Reserve Infantry Regiment 76 (RIR 76) of the 17th Reserve Division relieved IR 163 at the Saillisels, both regiments having fought against the British on the Somme earlier in the battle. The troops of the 16th Division had spent several days digging part of R. II Stellung by day and night in the rain, after marching 9.3 mi (15 km) from bivouacs in muddy fields, without means of getting dry, before receiving the order to move forward to the front line. On 10 October, another order came that the division would not be relieved for some time and must keep troops in reserve back in R. I Stellung. The front line was hard to define and led IR 68 and RIR 76 to argue over the inter-regimental boundary; French attacks and artillery-fire had already made the southern approach to the village untenable. The troops were encouraged by the evidence of the greater effort in the air being made over the Somme, reporting that the "aerial plague was less intense" than during their first tour.[49]

The 18th Reserve Division relieved the 52nd Reserve Division in late September and Reserve Infantry Regiment 84 on the left of the division lost 70 prisoners on 7 October. The British 20th Division took prisoners from Reserve Infantry Regiment 72 (7th Reserve Division) on the Gueudecourt–Beaulencourt road and Reserve Infantry Regiment 66 to the left.[48] Reserve Infantry regiments 36 and 72 (7th Reserve Division) lost prisoners at Rainbow Trench.[30] Snag Trench was held by III Battalion, BRIR 16 of the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division.[50] From 7–8 October, the British took 528 prisoners from Infantry regiments 360, 361, 362 of the 4th Ersatz Division, the I Battalion, Infantry Regiment 360 having been attacked during a relief by III Battalion, Infantry Regiment 360.[51] The 47th Division captured 84 prisoners of Reserve Infantry Regiment 31 (RIR 31) and 84 of the 18th Reserve Division. RIR 86 had moved left to close a gap made by the French, which moved RIR 31 opposite the British right flank.[52] In the 16th Division area opposite the French, IR 68 and IR 28 made several counter-attacks against French troops who had reached the church in Sailly, greatly helped by the German artillery which inflicted many French losses before the fighting closed to hand-to-hand.[53]

The new tactic of holding the front line with the minimum of men increased the burden on German artillery, which had to commence firing as soon as the French or British attacked but the extent of Allied artillery-fire forced the gunners to rely on flares from the front line instead of telephones. A field-gun regiment at the Nurlu–Péronne-Moislains–Templeux-la-Fosse crossroads covered the defences of St Pierre Vaast wood, 3.1–3.7 mi (5–6 km) away, from open positions vulnerable to French shelling. The distance from the wood was too great for observed fire; when shooting from the map, shell dispersion made for a large beaten zone, impossible to correct and some shells fell short onto German positions, depite careful fire control and gun laying. Steel was being used instead of brass for shell cases, which caused stoppages but the artillery still managed to fire 2,200–4,700 shells per day.[54]

12 October

The 16th Division at the Saillisels repulsed several attacks in the morning and then received a bombardment of "staggering intensity", before the French attacked again. Infantry Regiment 68 lost another 102 casualties but held on with IR 76 which was relieved that night. Liaison between the Bavarians and the 16th Division was poor and both regiments argued about responsibility for a gap between them. The companies of the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division on the Bapaume–Albert road opposite the British, were down to about 35 men each, all suffering from dysentery, exhaustion, hunger and exposure, to hold an area of 3,300 ft × 4,900 ft (1,000 m × 1,500 m).[55] Reserve Infantry Regiment 31 recorded many losses at Zenith Trench.[35] The 19th Reserve Division had relieved the 7th Reserve Division and on the right the 6th Division had moved up and taken over the left of the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division opposite the III Corps of the British Fourth Army. Reserve Infantry Regiment 92 of the 19th Reserve Division was opposite the left of the British 6th Division. About 150 prisoners were taken from Infantry Regiment 64 of the 6th Division during the loss of Hilt Trench, the left flank being rolled up. A counter-attack stopped the British advance but contact with Reserve Infantry Regiment 92 of the 19th Reserve Division on the left was lost.[56]

Infantry Regiment 24 of the 6th Division and parts of Bavarian Reserve Infantry regiments 16 and 21 of the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division were opposite the 30th Division. Snag Trench was held by Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 20.[57] After the fighting on 12 October, the 2nd Bavarian Division relieved the 18th Reserve Division, the 40th Division relieved the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division on the night of 12/13 October and the 24th Division took over from the 4th Ersatz Division.[58] On 12 October, men of the German 15th Division refused orders to move up to the front line.[59][lower-alpha 4] French attacks were made in the afternoons after artillery bombardments and on 14 October, IR 68 found that half its casualties had been caused by German artillery firing short. The dispute about regimental boundaries continued and on 15 October the French found the gap and got into Saillisel. Several determined counter-attacks were made to eject them but by 17 October the counter-attacks had failed.[61] (The Bavarians blamed the Prussians of IR 68, which after the war took 58 pages of the regimental history to explain that the position had been compromised all along, that German artillery had bombarded them constantly, tactical communication had been lost and orders could not be related to the ground.)[62]

18–20 October

The rest of the Saillisels had been held and the German hold on St Pierre Vaast wood stopped the French from rolling up the German defences from north to south.[63] The 4th Division took prisoners from Bavarian Infantry Regiment 15 of the 2nd Bavarian Division and the II Battalion, Bavarian Infantry Regiment 15 suffered 50 per cent casualties. Most of Reserve Infantry Regiment 92 was captured and Infantry Regiment 64 of the 6th Division lost 200 men of the I Battalion.[64] Infantry Regiment 181 of the 40th Division found that the mud reduced the effect of the British bombardment and the infantry were unable to make a quick advance. Prisoners were taken from I and II battalions, Infantry Regiment 104 at Snag Trench and the III Battalion conducted a counter-attack.[65] On 19 October, the storm detachment of the 40th Division counter-attacked in two columns with flame-throwers, a machine-gun section and the best men of I Battalion, Infantry Regiment 104; the advance of the left column was halted by one of the flame-throwers exploding. Most of the survivors of Infantry Regiment 104 were relieved by III Battalion, Infantry Regiment 134.[44] The trenches of Infantry Regiment 104 were smashed by artillery-fire and the troops were withdrawn, according to the new policy, of avoiding pointless casualties by abandoning outposts of no tactical value.[44]

24 October

Rupprecht wrote in his diary that the recapture of the north end of Sailly was needed to regain artillery observation but that this would have to wait for the arrival of the XV Corps (General Berthold von Deimling) with the 30th and 39th divisions. Below and the commander of the IX Reserve Corps, General Max von boehn, had agreed that the power of resistance of the Germans on the Somme was much reduced and that officer casualties meant that it could not be increased. The French First Offensive Battle of Verdun (20 October – 2 November) temporarily stopped the flow of reinforcements to the Somme front but substantial artillery and air reinforcements were already on the Somme. The decline in the power of the Anglo-French artillery caused by poor weather and Luftstreitkräfte attacks on artillery-observation machines, enabled the German infantry to mount a costly but successful defence, helped by the knowledge that the onset of winter would end the battle.[66]

Air operations

By October, the Germans had managed to assemble about 333 aircraft in 23 squadrons from Péronne to Hannescamps, 17 Feldflieger-Abteilungen with about 100 reconnaissance aircraft, 13 artillery flights (Artillerieflieger-Abteilungen) with about 53 aircraft, three bomber-fighter squadrons (Kampfgeschwader) and two independent flights with about 140 aeroplanes to escort them, mainly of C-type, two-seater, armed biplanes and three fighter squadrons (Jagdstaffel) with about 45 aircraft.[67] Jagdstaffel 2 (Jasta 2) Hauptmann Oswald Boelcke) had been established at Bertincourt on 27 August and on 16 September, received new Albatros D.I and D.II fighters.[68] The concentration of aircraft, particularly the superior fighters, enabled the Germans to challenge Anglo-French air superiority, at least for short periods.[69]

"Barrage flights" to stop aircraft crossing the German lines were abolished and airmen were ordered over the Anglo-French lines instead, to fight through to their objectives in large formations. Aircraft with more powerful engines, that could climb higher than British fighters had arrived in August and managed to photograph the battlefield. More balloon units arrived, which eventually had fifty balloons, half of those on the Western Front. All of the light motorised anti-aircraft guns in the army were sent to the Somme. Methodical observation of artillery-fire and the reforms introduced by Gallwitz made bombardments more efficient and German infantry began to regain confidence in the air arm.[69] On 6 October, the Imperial German Flying Corps (Fliegertruppen des deutschen Kaiserreiches) was reformed as the Luftstreitkräfte (German Air Force).[70]

1–11 October

During September, the monthly wastage (losses from all causes) in RFC fighters and long-range reconnaissance aircraft was 75 per cent and the new faster, more manoeuvrable German fighters coming into service, threatened Anglo-French air superiority on the Somme.[71] At 3:00 p.m. on 1 October, observers of 34 Squadron and 3 Squadron watched the attack by III Corps and the New Zealand Division of XV Corps on Eaucourt l'Abbaye and the defences either side, on a 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) front. The attack on Eaucourt failed but on the rest of the attack front the infantry followed a good barrage onto their objectives and were also able to send patrols into Le Sars. The commander of 34 Squadron, Major John Chamier reported that

At 3:15 p.m. the steady bombardment changed into a most magnificent barrage....the barrage appeared to be the most perfect wall of fire in which it was inconceivable that anything could live.... The 50th Division...were seen to spread out from the sapheads and forming up trenches and advance close up under the barrage, apparently some 50 yd (46 m) away from it. They appeared to capture their objective very rapidly and with practically no losses while crossing the open.... To sum up: the most startling feature of the operations as viewed from the air was (1) the extraordinary volume of fire of our barrage and the straight line kept by it, (2) the apparent ease with which the attack succeeded where troops were enabled to go forward close under it. (3) The promiscuous character and comparative lack of volume of the enemy's counter-barrage.

— John Chamier[72]

II Corps of the Reserve Army on the left of III Corps, had attacked at 3:00 p.m. but was repulsed by a huge amount of German artillery-fire and frequent counter-attacks. In three hours, RFC observers sent down 67 zone calls to the II Corps counter-battery group and 39 batteries were reported by observers in balloons.[72][lower-alpha 5] On 2 October, continuous rain began and eight German aircraft flew low over the British lines between Morval and Lesbœufs, where one was shot down by ground fire, while the British aircraft were on the ground. On 6 October, German aircraft had reconnoitred and several strafed troops of XV Corps. The Fourth Army attacked again on 7 October in dull and windy weather and the German airmen returned to the British artillery lines near Flers and Gueudecourt and directed German counter-battery fire onto the British guns.[74]

British fighter pilots from IV Brigade were sent to the scene but the Germans had gone by the time they arrived. RFC observers watched the British attack but the strong westerly wind made their aircraft appear to be stationary in the air, when the pilots turned into the wind to allow the observers to study the ground. German infantry fired on the aircraft, two crew were wounded and several aircraft had to be flown back to make emergency landings. Rawlinson complained at the quality of the reconnaissance reports, which with the lack of observation during the rain delays before the attack, led to the British bombardments and barrages being inaccurate, which contributed to the failure of the Fourth Army except east of Gueudecourt and at Le Sars. The German counter-barrage had been prompt and accurate, helped by the success of the reconnaissance flights before the attack.[74]

On 9 October, German aircraft bombed the rear areas of III Corps at 11:20 p.m. and within minutes four pilots from 18 Squadron and 21 Squadron, were dispatched to raid illuminated aerodromes from which the bombers had come but none were seen; Cambrai station and villages around Bapaume were bombed instead. A train hit earlier by 13 Squadron, which had also bombed Bapaume and Quéant stations, was hit again. Next day the weather improved and every British offensive patrol was attacked; Sopwith 1½ Strutters from 70 Squadron fought seven German fighters over their airfield at Vélu; other British aircraft joined in but found it impossible to keep the German aircraft in their sights because of their manoeuvrability. The German aircraft eventually flew away after one aeroplane each was shot down; three more German aircraft were lost and a British aircraft was shot down into the British lines near Morval from which the crew escaped. Another aeroplane force-landed at Pozières and a 23 Squadron F.E.2b crashed into a shell-hole with a dead pilot. During the night, 18, 19 and 13 squadrons bombed Cambrai and Vitry stations and the aerodrome at Douai.[75]

12–21 October

On 12 October, the Fourth Army attack was repulsed except near Gueudecourt, partly because of a lack of air observation, which led to an inadequate preparatory bombardment. The weather remained bad until 16 October when three aircraft of 18 Squadron bombed Cambrai station, one of which was shot down as they returned. German aircraft also bombed the airfield of 9 Squadron, wounding two ground staff and destroying one aeroplane and damaged another. Seven BE 12s of 19 Squadron bombed Hermies station and the airfield in the morning, then Havrincourt and Ruyaulcourt in the afternoon, losing two aircraft. The reconnaissance and artillery-observation aircraft of IV and V brigades flew many sorties against much German fighter opposition. A 15 Squadron aircraft was attacked by five fighters near Hébuterne and shot down and another aircraft was attacked over Warlencourt and returned with a wounded observer. IV Brigade offensive patrols lost one aircraft and had one pilot wounded, shooting down three German aircraft; another was shot down by a V Brigade offensive patrol.[76]

The better weather continued on 17 October and a supply dump was blown up at Bapaume station. A reconnaissance by Third Army aircraft at the north end of the Somme front, met twenty German fighters and two aircraft were shot down by each side. A British aircraft was driven down by German fighters and two German aircraft were forced down by 24 Squadron near Vélu; rain and sleet then stopped flying for two days.[77] On 20 October, aircraft of 11 Squadron on photographic reconnaissance near Douai, were attacked by Jasta 2, which shot down two aircraft and damaged two more. Thirty-three German aircraft crossed the British front line and made many attacks on British aircraft; three German aircraft were shot down and seventeen claimed damaged. German night bombers attacked Querrieu, Corbie and Longueau, where an ammunition wagon was blown up; British aircraft attacked Vélu and Péronne. Quéant station was bombed by thirty aircraft and escorts and one bomber was shot down. After the bombers reached British lines, one of the escorting Nieuport 17s turned back but was forced down in a dogfight with a faster German aircraft. On other parts of the Somme front two German aircraft were shot down, three damaged and ten driven down.[78]

22 October–November

On 22 October there were many sorties by German flyers. Six aircraft attacked a 1½ Strutter of 45 Squadron and wounded the observer, who shot one down. Later in the day, three 45 Squadron aircraft were shot down and an F.E.2b shot down one aircraft and damaged another, before the observer was mortally wounded; four British aircraft were shot down beyond German lines. During 23 October, two Reserve Army artillery observation aeroplanes were shot down by Jasta 2. On 26 October, despite poor weather both sides flew many sorties; a fight between five Airco DH.2s of 24 Squadron and twenty Halberstadt D.IIs was indecisive but later in the day, eight aircraft led by Boelcke, shot down one British observation aircraft, forced down two more and a British fighter which intervened. One German fighter was then shot down when a formation of British fighters from 32 Squadron turned up. Boelcke was killed on 28 October, when he collided with a German aircraft during an attack on two British fighters, which returned safely.[79]

For the rest of the battle of the Somme, both sides flew in rain, mist, sleet and westerly gales, often at dangerously low heights, to direct artillery and attack troops with guns and bombs. 3 November was a clear day and German aircraft shot down five British aircraft. On the night of 6 November German night bombers hit an ammunition train near Cerisy, which exploded next to a cage for German prisoners of war and devastated the area. Better weather came on 8 November and many German aircraft made ground attacks on British troops, a tactic which the Luftstreitkräfte began to incorporate systematically into its defensive operations. The British attempted to divert German attention next day, with bombing raids on Arleux and Vraucourt. The raid on Vraucourt by twelve bombers and fourteen escorts became the biggest air fight of the war, when approximately thirty German aircraft attacked the formation as it crossed the front lines. Most of the bombs were dropped over the target but six British aircraft were shot down and three German aircraft were claimed. Three more British aircraft were shot down later in the day; one pilot was killed, one wounded and an observer were wounded in aircraft which returned.[79]

The railway station at Vitry and German airfields at Buissy, Vélu and Villers were attacked after dark, while German night bombers attacked the airfield at Lavieville. The British attacked Valenciennes aerodrome next morning, where five parked aircraft, hangars and sheds were bombed. Next day, German air operations were less extensive; three aircraft were shot down and three damaged for the loss of one British aeroplane. Naval 8 drove down two German aircraft on 10 November and overnight 18 Squadron retaliated for the attack on their airfield at Lavieville by bombing Valenciennes, Vélu, transport on the Bapaume road, balloon sheds, a train near St. Léger and a second train which was set on fire; a German headquarters at Havrincourt Château and Douai aerodrome were also attacked. German bombers attacked Amiens station and returned on the night of 10/11 November, when one aircraft was forced down with engine-trouble and the crew captured.[80]

Flanking operations

Tenth Army

The Tenth Army attacked from 10–11, 14 and 21–22 October during the Battle of Le Transloy, after being reinforced by the XXI Corps (General Paul Maistre) and the II Colonial Corps (General Ernest Blondlat).[81] On 10 October the army attacked on a 6.2 mi (10 km) front in the centre of the army area towards Pressoir, Ablaincourt and Fresnes.[lower-alpha 6] The French captured the German second position around Ablaincourt and took about 1,400 prisoners but south of Estrées, the attack by the 51st Division on Chaulnes was contained in Bois 4 to the north-west. On 14 October, an attack by the 10th Colonial Division and two other divisions on the left flank, next to the Sixth Army boundary, captured the trenches opposite and took about 1,000 prisoners; the French then paused to consolidate the ground around Ablaincourt, which had turned into a vast lake of mud and repulsed several German counter-attacks. The army began preparations for an attack later in October to capture the Butte de Fresnes and cut the Chaulnes–Péronne railway but the weather, the state of the ground, exhaustion of the infantry and the increased powers of resistance of the German 2nd Army slowed the French advance.[82]

The Tenth Army had failed to advance on the northern flank against Barleux in the Sixth Army area, where the XXXIII Corps on both sides of the Somme, had attacked again in the south on 18 October, to counter German mining and improve the line from La Maisonnette north to Biaches.[83] An attack to clear the approaches to the higher ground on which lay Villers-Carbonnel and Fresnes to the south-east was forestalled on 29 October, when the Germans bombarded La Maisonette for eight hours with high explosive, gas and lachrymatory shell and then the 206th Division attacked with Infantry Regiment 359. A battalion of the 97th Infantry Regiment was overrun and 450 prisoners taken, which left a gap in the French line for several days and the attack on Barleux had to be cancelled. On the right (southern) flank of the army, the 51st Division was unable to advance further in Bois 4 on 11 October. During the night a counter-attack by German storm-troops and a flame-thrower detachment destroyed a battalion of the 25th Regiment and a French attack on 21 October, began a period of local attacks and counter-attacks which lasted into November.[84]

Sixth Army

The Sixth Army attacked on 7, 12–13, 15 and 18 October.[81] Opposite the Sixth Army, R I Stellung (Rückstellung, reserve position) the fourth German defensive position built on the Somme, ran along a dip at the top of the shallow valley between the Saillisels and Le Transloy, in front of which the sunken road from Le Transloy to the Morval–Saillisel road, known as Baniska and Tours trenches, had also been fortified. On the right flank of the attack, the Saillisels were covered by the Prilip to the Portes de Fer and Négotin line just east of Rancourt, which met the west end of St Pierre Vaast wood at Reuss Trench and the Carlsbad, Terplitz and Berlin trenches about 6,600 ft (2,000 m) further back. A strong point around Bois Tripot and Château Sailly-Saillisel covered the southern approaches to the villages. The villages were bombarded by super-heavy 270 mm, 280 mm and 370 mm mortars ready for the attack on 7 October when the Fourth Army to the north attacked.[85]

7 October

In the centre, the I Corps (General Adolphe Guillaumat) captured the line from Prilip to Portes de Fer to Négotin in early October and on 7 October, the 40th Division captured Terplitz and Berlin trenches, formed a flank on the south-west fringe of St Pierre Vaast Wood and gained a small part of Reuss Trench (later lost). The 56th Division to the left managed to advance 3,900 ft (1,200 m) up the slope west of the Saillisels, captured Carlsbad Trench and gained a footing in the Bois Tripot strongpoint beyond, which gave the French observation of the ground towards the Péronne–Bapaume road and the Saillisels.[86] The attack was the most successful on the north side of the Somme but fell far short of Rocquigny and on the left flank I Corps, which had been in the line since August, was relieved by the IX Corps (General H. F. A. Pentel) ready for the next attack on 12 October. On the right flank, the attack of the XXXIII Corps (General A. Nudant) south of Bouchavesnes from 6 to 7 October failed, due to an ineffective bombardment and offensive operations were suspended for the winter.[87]

12–18 October

In the second week of October, the XXXII Corps (General Henri Berthelot until 16 October then General M. E. Debeney) took over the right flank of I Corps and on 12 October, the corps got into Sailly-Saillisel but was forced out by German counter-attacks. On 15 October, the 66th Division exploited a crushing bombardment to capture the remainder of Bois Tripot, Château Saillisel; the 152nd Infantry Regiment and the 68th Battalion Chasseurs Alpins infiltrated between Prussian and Bavarian positions and spent the next six days fighting hand-to hand in the ruins. The 94th Infantry Regiment of the 66th Division held on against several German counter-attacks around the Péronne–Bapaume and Sailly-Saillisel to Moislains crossroads up to 29 October.[lower-alpha 7] On the right flank, the XXXII Corps Chasseurs gained a foothold in Reuss Trench but more attacks to capture the east side of Sailly-Saillisel were postponed because of bad weather until 5 November and took until 12 November to complete.[89]

The 18th Division (IX Corps) attack on Bukovina Trench failed as did several later attacks and Fayolle sacked Pentel, despite the careful training he had given the corps before it entered the line. The 18th Division reported afterwards that ground observation posts had only a partial view over the trench, air observation was limited by frequent fog, rain and high winds. The French approach was up a 6,600 ft (2,000 m) slope, full of shell-craters and mud dotted with hidden machine-gun nests, dominated by German artillery and observation aircraft. French light machine-guns jammed and the infantry struggled through knee-high mud. On 17 October an attack on Baniska Trench failed when the French barrage fell short onto the 32nd Infantry Regiment as it waited for zero hour in an advanced jumping-off trench. The German counter-bombardment caught the support waves in the French front line and the advanced troops were caught in crossfire from machine-gun nests set up in front of Baniska Trench. The troops furthest forward were forced under cover, short of the trench and those on the flanks were unable to advance, which left the 32nd Infantry Regiment in a salient and bombarded by their artillery again, losing 130 casualties in the attack.[90] Baniska Trench was eventually captured by the 152nd Division (General Andrieu) on 1 November, after Fayolle over-ruled Andrieu and insisted on an attack, which apparently surprised the Germans, who did think that one could occur in such abysmal conditions.[90]

Reserve Army

The Reserve Army of the BEF (renamed Fifth Army on 29 October) continued its attacks from Courcelette near the Albert–Bapaume road, west to Thiepval on Bazentin Ridge. The Reserve Army attacked on 1, 8, 21 and 25 October. Many smaller attacks were also made between frequent rainstorms, which turned the ground and roads into rivers of mud and grounded aircraft. German forces at the east end of Staufen Riegel (Regina Trench) and in the remaining parts of Schwaben-Feste (Schwaben Redoubt) to the north and Stuff Redoubt (Staufen-Feste) north-east of Thiepval, fought a costly defensive battle but Stuff Redoubt was captured on 9 October and the last German position in Schwaben Redoubt fell on 14 October, exposing German positions in the Ancre valley to British ground observation.[91]

A retreat up the Ancre valley was contemplated by Ludendorff and Rupprecht but rejected, due to the lack of better defensive positions further back, in favour of counter-attacks desired by Below the 1st Army commander. Gallwitz noted in early October that so many of his units had been transferred north of the Somme and that he had only one fresh regiment left in reserve. The German counter-attacks were costly failures and by 21 October, the British had advanced 500 yd (460 m) and taken all but the last German foothold in the eastern part of Staufen Riegel (Regina Trench). From 29 October to 9 November, British attacks were postponed due to rain and fog.[92]

Aftermath

Analysis

Wilfrid Miles

In 1938, Wilfrid Miles, the British official historian, wrote that by 12 October, the Germans were used to afternoon attacks; British battalions were at half-strength with only 400 men, many being poorly-trained recruits. Lacking air observation for reconnaissance and artillery-observation in the poor weather, the infantry had struggled to advance towards German defences. The German machine-guns had been moved back to concealed positions beyond the depth of the British barrages, to sweep the attack front from long range. Rawlinson decided that the German defences would have to be subjected to a methodical bombardment and that the infantry must prepare more routes of supply from the rear and dig assembly trenches parallel to their objectives; Cavan suggested beginning a creeping barrage just beyond objectives and firing lots of smoke shells to hamper German observation but none were available. By mid-October, air reconnaissance was impossible because of rain and mist and artillery-observation could not be conducted on any great scale.[93]

Shell bursts were smothered, guns became too worn for accurate fire and sank into the mud; the supply of ammunition was slowed by the condition of the ground and German bombardments. After the results of the attack on 18 October were known, the scope of the offensive was reduced and then washed out by more rain until 3 November. Cavan objected to more attacks on Le Transloy, except from the south, XIV Corps having already suffered 5,320 casualties. Rawlinson and then Haig had agreed to stop the attack but changed their minds when the French insisted on an attack by the Sixth Army. XIV Corps was ordered to make a local attack to the east and north-east of Lesbœufs and the French told that only a general pressure would be exerted by rest of the Fourth Army. On 6 November, attacks were only to be made to stop the Germans from moving troops from the Western Front and to support the attacks of the Sixth Army.[94]

Andrew Simpson

In 1995, Simpson wrote that the inability of the British artillery adequately to respond to the changes of German tactics may have been caused by the supply difficulties in October, when the gunners lacked the ammunition to extend creeping barrages all the way to the far side of German defences. Guns were worn out, ammunition had three types of propellant with inconsistent characteristics, all the ammunition was damp and corrections for atmospheric conditions were insufficient to regain accuracy, without observation of targets or information on the fall of shot from artillery-observation aircraft.[95] In 2001, Simpson described the process of forming plans by the Fourth Army headquarters to be one of consultation and negotiation with corps commanders, provided that decisions were compatible with the corps artillery plan, which was derived from the army plan. Corps then set boundaries and let divisional commanders have discretion within them. By October corps headquarters were aware of the importance of passing information from contact-patrol aircraft and other sources forward to divisions, the corps headquarters developing into information clearing-houses by the end of the battle.[96]

Gary Sheffield

In 2003, Sheffield described the tactical conditions on the Fourth Army front in similar terms to that of Wilfrid Miles, the official historian and that attacks continued in mud, which slowed movement to a crawl and in which had taken ten hours to move an Australian brigadier to a dressing station. Charles Bean, the Australian official historian called the conditions "the worst ever known to the First A. I. F.". Sheffield wrote that Haig was in a coalition "strait-jacket" with the French as the senior partners, which other writers and historians had underestimated. Joffre had wanted another offensive towards Bertincourt, Bapaume and Achiet-le-Grand and the Sixth Army continued its attack, which Haig felt bound to support. Sheffield wrote that Philpott's view that Haig continued the offensive "in the broader interests of the alliance", was correct.[97]

In 2011, Sheffield wrote that the new German defences built behind the third position in the onset of autumn required a series of bite and hold attacks, which were beyond the ability of the British to arrange in time to reach open country. In late September, Haig had ordered an ambitious three-army offensive operation toward Cambrai but despite showing increasing tactical skill and inflicting many losses on the Germans, the territorial gains were "miserly". Haig persisted because he believed that attrition was working, the British Expeditionary Force was improving and that he overestimated the capacity of the armies in a wet and muddy season. The pressure from Joffre to continue was also significant, Haig wrote sympathetically of Cavan's protest in November but that the French could not be left in the lurch. In late October Haig reminded Joffre that although subordinate to French strategy he retained discretion over the operational and tactical matters of where, when and how.[98]

Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson