| Battle of the Dalmatian Channels | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence | |||||||

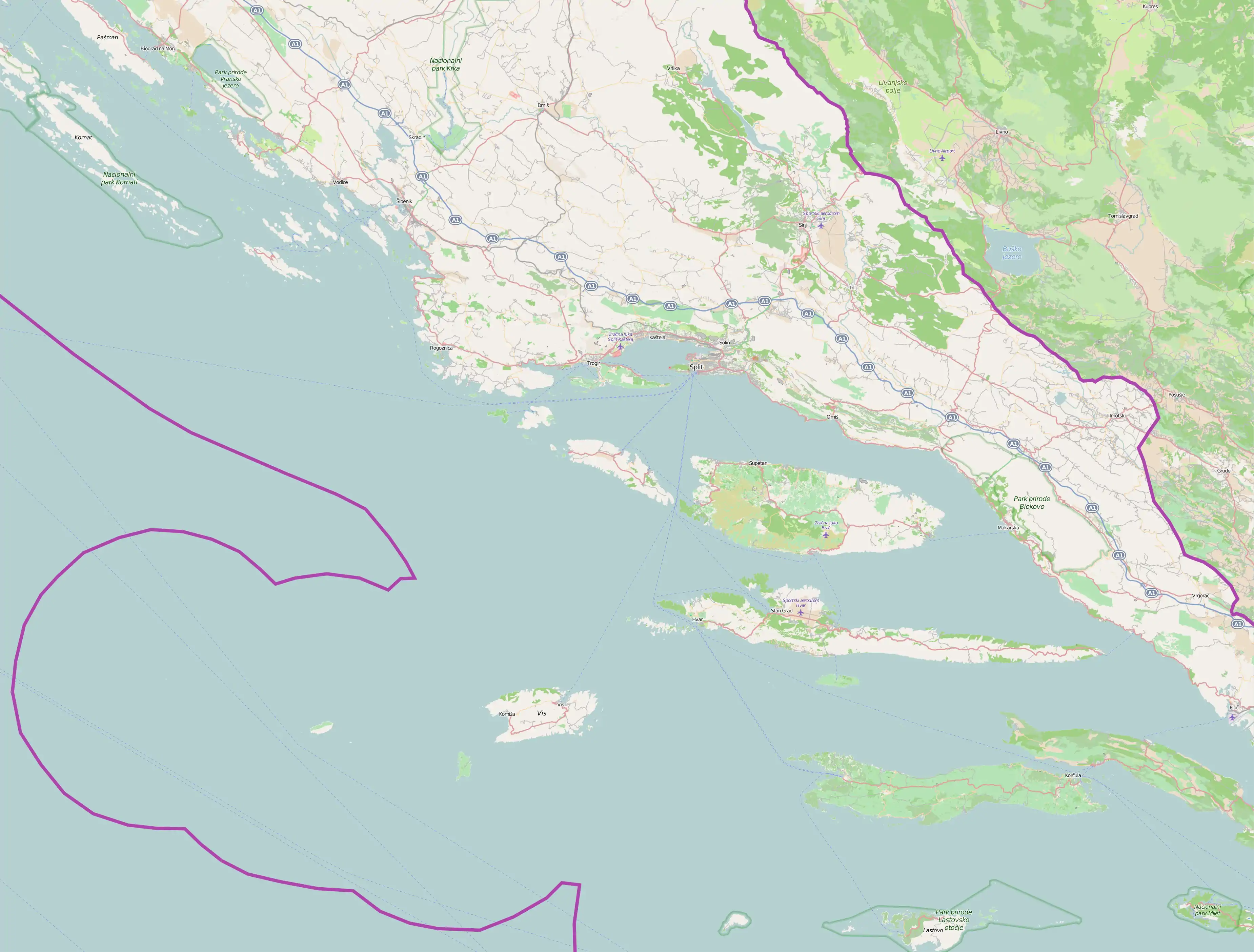

A location map of the central Dalmatia, and location of the area shown on the map of Croatia (inset, red) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Coastal artillery Naval commandos |

2 frigates 6-7 missile boats 2 torpedo boats 4 patrol boats 3 minesweepers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2 killed |

22 killed 1 patrol boat captured 2 minesweepers sunk 1 minesweeper damaged 2 aircraft destroyed | ||||||

|

2 civilians killed 9 civilians wounded 2 civilian ferries damaged | |||||||

The Battle of the Dalmatian Channels was a three-day confrontation between three tactical groups of Yugoslav Navy ships and coastal artillery, and a detachment of naval commandos of the Croatian Navy fought on 14–16 November 1991 during the Croatian War of Independence. On 14 November, the commandos torpedoed the Mirna-class patrol boat PČ-176 Mukos close to the island of Brač in the Split Channel of the Adriatic Sea, prompting a Yugoslav naval bombardment of Brač and Šolta Island the same day. The drifting Mukos was salvaged by Croatian civilian boats and beached at Nečujam bay.

The next day, a group of Yugoslav Navy vessels, organised into the Kaštela tactical group (TG), deployed to the Split Channel, and bombarded the city of Split in retaliation for the loss of Mukos. In return, Croatian coastal artillery engaged the Kaštela TG. To draw off some of the artillery fire, the Yugoslav Navy deployed another group of vessels from the island of Vis, organised as the Vis TG, south of Šolta, where it was engaged by more Croatian artillery. The Kaštela TG retreated east and joined with the Ploče TG, consisting of three minesweepers.

On 16 November, the combined Yugoslav force sailed through the Korčula Channel—a strait separating the islands of Hvar and Korčula—to reach safety at the Yugoslav Navy base at Vis. The warships were then engaged by Croatian coastal artillery deployed on Korčula and the Pelješac Peninsula, losing two minesweepers to the artillery fire in the process.

The battle marked the last deployment of the Yugoslav Navy into one of the Dalmatian channels, the loosening of the naval blockade of the Croatian coast imposed in September, and the largest Croatian Navy operation in the war. The Croatian Navy later towed the grounded Mukos to Šibenik, repaired the vessel and put her into service as OB-62 Šolta. During the battle, 22 Yugoslav Navy crewmen, two Croatian gunners and two civilian sailors in Split were killed. Thirty-three Yugoslav officers were charged in relation to the naval bombardment by Croatian authorities.

Background

In 1990, following the electoral defeat of the government of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, ethnic tensions increased. The Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija – JNA) confiscated Croatia's Territorial Defence Forces' (Teritorijalna obrana – TO) weapons to minimize resistance.[1] On 17 August, the tensions escalated into an open revolt by Croatian Serbs,[2] centred on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around Knin,[3] and parts of Lika, Kordun, Banovina, and eastern Croatia.[4] This was followed by two unsuccessful attempts by Serbia, supported by Montenegro and Serbia's provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo, to obtain the Yugoslav Presidency's approval for a JNA operation to disarm Croatian security forces in January 1991.[5]

After a bloodless skirmish between Serb insurgents and Croatian special police in March,[6] the JNA, supported by Serbia and its allies, asked the federal presidency to give it wartime authorities and to declare a state of emergency. The request was denied on 15 March and the JNA came under the control of Serbian president, Slobodan Milošević. Preferring a campaign to expand Serbia rather than to preserve Yugoslavia, Milošević publicly threatened to replace the JNA with a Serbian army and declared that he no longer recognized the authority of the federal presidency.[7] By the end of March, the conflict had escalated into the Croatian War of Independence.[8] The JNA intervened; they increasingly supported the Croatian Serb insurgents and prevented Croatian police from intervening.[7] In early April, the leaders of the Croatian Serb revolt declared their intention to integrate the area under their control, known as SAO Krajina, with Serbia. The government of Croatia viewed this declaration as an attempt to secede.[9]

In May 1991, the Croatian government responded by forming the Croatian National Guard (Zbor narodne garde – ZNG),[10] but its development was hampered by a United Nations (UN) arms embargo and the Yugoslav Navy's blockade of the Adriatic coast, both of which were introduced in September.[11][12] Following the Battle of the Barracks, the ZNG acquired a significant stock of weapons and ammunition,[13] including 34 Yugoslav Navy vessels moored in Šibenik.[14] Croatian forces using naval mines deployed in Kaštela Bay rendered the Yugoslav Navy base at Lora in Split inaccessible.[15] On 8 October, Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia,[16] and a month later the Croatian National Guard was renamed the Croatian Army (Hrvatska vojska – HV).[10] Late 1991 saw the fiercest fighting of the war; the 1991 Yugoslav campaign in Croatia culminated in the Siege of Dubrovnik[17] and the Battle of Vukovar.[18]

During the first days of November, the Yugoslav Navy stopped the Libertas convoy twice for inspection between the islands of Brač and Korčula as it enforced the blockade. The convoy of 40 small boats led by the ferry Slavija was on its way to resupply Dubrovnik and retrieve refugees from the besieged city.[19] On 11 November, the Maltese-flagged coaster Euroriver, manned by a Croatian crew, was sunk by gunfire off Šolta Island.[20]

Order of battle

Despite the capture of the Yugoslav Navy vessels in September, Croatia's coastal defences relied on captured coastal artillery on the mainland and the nearby islands.[21] In central Dalmatia, these included three batteries on the mainland between Šibenik and Split, 90-millimetre (3.5 in) guns on Žirje Island, a 100-millimetre (3.9 in) battery near Zečevo and 88-millimetre (3.5 in) guns on Smokvica Island near Primošten. Four coastal artillery batteries on islands off Split—the 88-millimetre Marinča Rat on the island of Šolta, the 85-millimetre (3.3 in) Ražanj battery on the island of Brač, and the 88-millimetre battery Ražnjić and the 85-millimetre battery Privala on the island of Korčula—were captured. Some the guns captured on Žirje and Šolta were removed and used to set up additional coastal artillery batteries at Kašjuni and Duilovo in Split.[14] Additional batteries were set up in Lovište at the tip of the Pelješac Peninsula,[22] and in Blace and Črna Luka on Korčula on the coast north of Smokvica and Vela Luka.[23] The battery deployed to Črna Luka contained 76-millimetre (3.0 in) M1942 (ZiS-3) guns. A naval commando detachment from the Croatian Navy was deployed to the western Brač. The coastal artillery was subordinated to the Croatian Navy and commanded by Admiral Sveto Letica.[22]

The Yugoslav Navy deployed three tactical groups (TGs) named Kaštela, Vis and Ploče off the coast of central Dalmatia from its bases on the islands of Vis and Lastovo. The Kaštela TG was deployed to the sea off Split and north of the islands of Šolta and Brač. It consisted of Koni-class frigate VPBR-31 Split, Končar-class fast attack craft RTOP-401 Rade Končar and RTOP-403 Ramiz Sadiku, Osa-class missile boat RČ-306 Nikola Martinović, Shershen-class torpedo boats TČ-220 Crvena zvezda and TČ-224 Pionir II and two Mirna-class patrol boats, including PČ-176 Mukos.[22] Kaštela TG may have also included an additional Osa-class missile boat.[24] The Ploče TG, deployed to the sea between the mainland and Brač to the east of the Kaštela TG, consisted of three minesweepers: ML-143 Iž, ML-144 Olib and ML-153 Blitvenica. The Vis TG was deployed off the western tip of the island of Hvar.[22] It consisted of a Kotor-class frigate VPBR-34 Pula commanded by Captain Ilija Brčić,[25] one Končar-class fast attack craft, two Osa-missile boats and two Mirna-class patrol craft.[26] The Yugoslav Navy fleet was under overall command of Rear Admiral Nikola Ercegović.[27]

Timeline

14 November

On 14 November at 5:34 p.m., the Croatian naval commandos attacked Mukos off Brač using a torpedo fired from the island.[28] Her crew reported an explosion in the bow of the ship and requested assistance from the Kaštela TG because she started to sink. The Kaštela TG dispatched Pionir II, which reached Mukos shortly afterwards and had transferred the crew of the damaged vessel by 6:10 p.m. Mukos was left to drift towards Šolta with her bow fully submerged and containing the bodies of three dead crew members. For nearly the entire night, the Kaštela TG directed gunfire against the Milna and Stomorska areas of Šolta to draw fire from Croatian coastal artillery. However, the coastal artillery deployed in the targeted areas did not return fire. Additional Yugoslav vessels sortied from Vis but returned to their base before the morning without transiting the Split Entrance—the strait between the islands of Brač and Šolta. By that time, the naval gunfire also died down. The Ploče TG remained in their assigned area of patrol.[22]

15 November

On 15 November at 6:42 a.m., the Kaštela TG commenced a naval bombardment of targets in Split and on the islands of Brač and Šolta. The order was issued aboard VPBR-31 Split and the JNA Maritime Military Sector command and JNA bases in Split were advised of the attack. The JNA based in Split did not join the bombardment.[22] Letica notified the JNA Maritime Military Sector commanding officer Major General Nikola Mladenić[29] of the attack, but Mladenić said he could not control the situation because his headquarters was denied a supply of electricity. The European Community Monitor Mission (ECMM) was also notified; they promised to make efforts to stop the bombardment. Shortly after, Letica ordered the coastal artillery to commence fire against the Kaštela TG. Besides several near-misses, the coastal artillery fire scored a direct hit against VPBR-31 Split,[22] that was attributed to the Marinča Rat-based battery on Šolta.[30] Croatian sources said Mladenić ordered the bombardment in retribution for the loss of Mukos.[31]

In response to the difficult position of the Yugoslav Navy vessels north of Šolta and Brač, the Vis TG led by Pula sailed north from the island of Vis to draw some of the artillery fire away from the Kaštela TG. As the ships approached the Split Entrance, they made a radar contact sailing away from Split towards open sea at a high speed. Pula, attempting to enforce the blockade imposed in September, requested the vessel by radio to stop for an inspection. The vessel failed to respond and Pula fired several shots in front of it before Brčić noticed that it was a hydrofoil carrying an ECMM team and flying the flag of Europe. He abandoned the pursuit and proceeded to Šolta.[25]

The Vis TG came under fire from the coastal artillery when it arrived within 7 to 8 nautical miles (13 to 15 kilometres; 8.1 to 9.2 miles) of Šolta. In response to the incoming fire, Pula fired her 76-millimetre (3.0 in) bow-mounted gun against targets on Brač and Šolta. Croatian sources said that approximately 800 rounds were fired indiscriminately, striking civilian targets, while Brčić said the TG under his command acted only against artillery located outside residential areas. Pula also fired four salvos of depth charges using her RBU-6000 rocket launcher while the land was outside its range to draw greater attention from the artillery gunners.[25]

The Kaštela TG started to withdraw east at approximately 8:00 a.m., fearing the shortest available route to Vis might be mined in the area of Split Entrance. It reached the eastern tip of Brač by 8:30 a.m. At 9:28 a.m., three Yugoslav Air Force J-21 Jastrebs flew low over Brač and Šolta; minutes later, two were reportedly shot down by anti-aircraft artillery.[22] Six Yugoslav jets were sortied against targets on Brač and Šolta.[25] Following the naval action that morning, Croatian civilian boats from Šolta towed the partially submerged Mukos to Nečujam Bay and ran it aground there. In the afternoon, the Kaštela TG and the Ploče TG linked up east of the island of Hvar.[22]

16 November

On 16 November at 11:00 a.m., the Kaštela and Ploče TGs started to assemble at the eastern end of the Korčula Channel, which separates the islands of Hvar and Korčula just north of Cape Lovište at the westernmost tip of the Pelješac Peninsula. The relatively slow minesweepers Iž and Olib, which belonged to the Ploče TG, were hit in the bow and the engine room respectively, by the 76-millimetre (3.0 in) guns at Lovište. To assist the minesweepers, Split turned around to engage the artillery at Cape Lovište while the minesweepers sailed north closer to the Hvar shore in increasingly thick fog.[22]

At 3:30 p.m., the Kaštela TG turned around once more to attack Cape Lovište, but were engaged by nearby coastal artillery located on Korčula. Blitvenica was damaged in the shooting and the entire naval force moved north-west towards Šćedro Island.[22] Iž sustained heavy damage and ran aground in Torac Bay off Hvar, and was abandoned. Olib sank between Pelješac and Hvar.[32] Her crew were rescued by the remaining vessels in the group. At 7:00 p.m., the fleet sailed south from Šćedro towards the western part of Korčula, seeking shelter as the Sirocco wind strengthened. As the ships approached Korčula, they were fired upon by coastal artillery at Črna Luka and Cape Privala, forcing them to turn west towards Vis.[22] The Vis TG did not engage Croatian positions on 16 November.[25]

Aftermath

The Yugoslav Navy was defeated[33] and its ships did not sail north of the Split Entrance again. The battle was the largest engagement of the Croatian Navy during the war.[22] Two Croatian anti-aircraft gunners were killed in action on the island of Brač.[30] According to Mladenić, the Yugoslav Navy lost 22 seamen—including three aboard Mukos—two minesweepers and a patrol craft. The Yugoslav Air Force lost two aircraft but the pilots were rescued by a helicopter that sortied from Vis and picked them up from the sea. Croatian Navy divers later raised Mukos and she was towed to Šibenik by a Brodospas-owned tug.[22] She was repaired and turned over to the Croatian Navy as OB-62 Šolta.[32] Two civilians were killed and nine were wounded in the naval bombardment of Split.[34] The bombardment damaged the Archaeological Museum, Split Municipality Building, Arena Gripe, Public Sanitation Institute, the Technical School, and the ferries Bartol Kašić and Vladimir Nazor, which were moored in the Port of Split.[25] The two civilian fatalities were crew members of Vladimir Nazor.[22]

Croatian authorities charged 33 JNA officers—including Brčić who was tried in absentia and convicted to 15 years in prison—for the bombardment of Split, Šolta and Brač. Brčić, who later became a high-ranking officer of the Montenegrin Navy, was arrested in Naples in late 2007 when he travelled to a NATO function. He was not extradited to Croatia.[35] Most of the other charged officers were also tried in absentia. As of 2013, fifteen officers—including Brčić—were convicted, one was acquitted and seventeen cases were ordered by the Supreme Court of Croatia to be retried because of irregularities during previous trials.[31]

In Croatia, the events of 14 and 15 November 1991 are referred to as the Battle of Split (Bitka za Split)[25] or the Battle of the Split Channel (Boj u Splitskom kanalu),[22] while the events of 16 November are referred to as the Battle of the Korčula Channel (Bitka u Korčulanskom kanalu). The events spanning all three days of the Battle of the Dalmatian Channels are also referred to as the Battle of the Adriatic (Bitka za Jadran).[36]

Footnotes

- ↑ Hoare 2010, p. 117.

- ↑ Hoare 2010, p. 118.

- ↑ The New York Times & 19 August 1990.

- ↑ ICTY & 12 June 2007.

- ↑ Hoare 2010, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Ramet 2006, pp. 384–385.

- 1 2 Hoare 2010, p. 119.

- ↑ The New York Times & 3 March 1991.

- ↑ The New York Times & 2 April 1991.

- 1 2 EECIS 1999, pp. 272–278.

- ↑ Brigović 2011, p. 428.

- ↑ The Independent & 10 October 1992.

- ↑ CIA 2002, pp. 95–96.

- 1 2 Reljanović 2001.

- ↑ Busuttil 1998, p. 43.

- ↑ Narodne novine & 8 October 1991.

- ↑ Bjelajac & Žunec 2009, pp. 249–250.

- ↑ The New York Times & 18 November 1991.

- ↑ Mesić 2004, pp. 389–390.

- ↑ Hooke 1997, p. 203.

- ↑ DoD 1997, sect. 8, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Slobodna Dalmacija & 15 November 2004.

- ↑ Rizmaul 2012.

- ↑ Bernadić 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Index.hr & 29 July 2008.

- ↑ Urlić 2011.

- ↑ CIA 2002b, p. 163.

- ↑ Jane's 2005, p. 165.

- ↑ Brigović 2011, p. 438.

- 1 2 Slobodna Dalmacija & 16 November 2011.

- 1 2 Slobodna Dalmacija & 31 July 2013.

- 1 2 Nacional & 8 July 2008.

- ↑ Marijan 2012, p. 109.

- ↑ Brigović 2011, p. 437.

- ↑ Nacional & 24 July 2008.

- ↑ Menges 2008.

References

- Books

- Bjelajac, Mile; Žunec, Ozren (2009). "The War in Croatia, 1991–1995". In Charles W. Ingrao; Thomas Allan Emmert (eds.). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-533-7.

- Busuttil, James J. (1998). Naval Weapons Systems and the Contemporary Law of War. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198265740.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 9780160664724. OCLC 50396958.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995, Volume 2. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 978-0-16-066472-4.

- Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. London, England: Routledge. 1999. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–136. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Hooke, Norman (1997). Maritime casualties, 1963–1996. London, England: Lloyd's of London Press. ISBN 9781859781104.

- Mesić, Stjepan (2004). The Demise of Yugoslavia: A Political Memoir. Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9241-81-7.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918–2006. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Saunders, Stephen, ed. (2005). Jane's Fighting Ships 2005–2006. London, England: Jane's Information Group. ISBN 9780710626929.

- United States Department of Defense (1997). Bosnia: Country Handbook. Collingdale, Pennsylvania: Diane Publishing. ISBN 9780788147982.

- Scientific journal articles

- Brigović, Ivan (October 2011). "Odlazak Jugoslavenske narodne armije s područja Zadra, Šibenika i Splita krajem 1991. i početkom 1992. godine" [Departure of the Yugoslav People's Army from the area of Zadar, Šibenik and Split in late 1991 and early 1992]. Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian). Croatian Institute of History. 43 (2): 415–452. ISSN 0590-9597.

- Marijan, Davor (May 2012). "The Sarajevo Ceasefire – Realism or strategic error by the Croatian leadership?". Review of Croatian History. Croatian Institute of History. 7 (1): 103–123. ISSN 1845-4380.

- News reports

- Bellamy, Christopher (10 October 1992). "Croatia built 'web of contacts' to evade weapons embargo". The Independent.

- Bernardić, Stjepan (15 November 2004). "Admiral Letica je naredio: Raspali!" [Admiral Letica Ordered: Fire!]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian).

- Engelberg, Stephen (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times.

- Glavurtić, Tihana (16 November 2011). "Junaci sa Šolte i Brača ratne brodove jugomornarice natjerali na bijeg" [Heroes of Šolta and Brač Chased Away Yugoslav Navy Warships]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian).

- Jadrijević Tomas, Saša (31 July 2013). "Za napad na Split sudit će se dvanaestorici" [Twelve to Face Trial for Split Attack]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian).

- "Kapetan Brčić: Moj brod nije pucao na EU promatrače, ispalili smo granate upozorenja" [Captain Brčić: My Ship Did Not Shoot at EU Observers, We Fired Warning Shots] (in Croatian). Index.hr. 29 July 2008.

- "Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts". The New York Times. Reuters. 19 August 1990.

- Šimičević, Hrvoje (24 July 2008). "Talijanski sud oslobodio Iliju Brčića" [Italian Court Releases Ilija Brčić]. Nacional (weekly) (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 2013-10-02.

- Šoštarić, Eduard (8 July 2008). "Bitka za jedrenjak 'Jadran'" [Battle of Jadran Sailing Ship]. Nacional (weekly) (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 11 July 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (18 November 1991). "Croats Concede Danube Town's Loss". The New York Times.

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 April 1991). "Rebel Serbs Complicate Rift on Yugoslav Unity". The New York Times.

- Other sources

- Bernadić, Stjepan (September 2006). "Prvi brod Hrvatske ratne mornarice" [The First Croatian Navy Ship]. Hrvatski vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (105). ISSN 1333-9036. Archived from the original on 2013-10-02.

- "Odluka" [Decision]. Narodne novine (in Croatian) (53). 8 October 1991. ISSN 1333-9273. Archived from the original on 2009-09-23.

- Menges, Mirela (April 2008). "Željko Seretinek: Bitka za Jadran: Razbijanje pomorske blokade jadranskog plovnog puta 14.-16. studenoga 1991., Korčula, 2007" [Željko Seretinek: Battle of the Adriatic: Dismantling the Adriatic Seaway Blockade 14–16 November 1991, Korčula, 2007]. Hrvatski Vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (184). ISSN 1333-9036.

- Reljanović, Marijo (November 2001). "Hrvatska ratna mornarica u obrani Jadrana" [Croatian Navy in defence of the Adriatic]. Hrvatski Vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (77). ISSN 1333-9036. Archived from the original on 2013-10-02.

- Rizmaul, Leon (November 2012). "Vremeplov 16. studenoga 1991" [Timeline 16 November 1991]. Hrvatski Vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (408). ISSN 1333-9036. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic – Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 12 June 2007.

- Urlić, Ante (April 2011). "Vojnogeografska i strateška obilježja otoka Visa (II. dio)" [Military Geographic and Strategic Characteristics of the Vis Island (Part 2)]. Hrvatski Vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (341). ISSN 1333-9036. Archived from the original on 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2013-09-30.

.svg.png.webp)

_(1868-1918).svg.png.webp)